Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

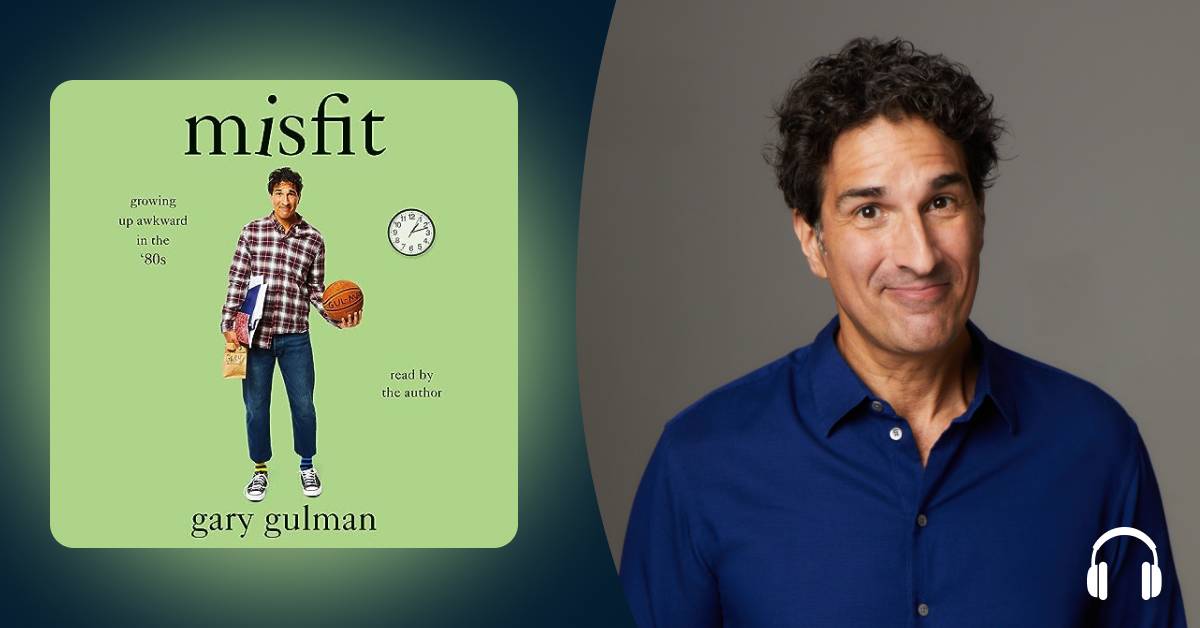

Aaron Schwartz: Hey there. I'm Audible editor, Aaron Schwartz, and I'm here speaking with one of our great working comedians today, Gary Gulman. Maybe you know him from some of his stand-up specials over the years—In This Economy or It's About Time, or one of my all-time favorites, the critically acclaimed The Great Depresh. He’s done various appearances on television from late night shows to guest roles on shows like Inside Amy Schumer and Crashing, and he regularly performs around the country. We're here today to talk about his new work, a memoir called Misfit: Growing Up Awkward in the '80s. Gary, thank you for taking the time.

Gary Gulman: Oh, thanks, Aaron. It's a pleasure.

AS: Before I get into the questions, I just want to say I've read and listened to a lot of books—I listen to books, 'cause I'm a company man—but I don't think I've ever related to something exactly as I have with this.

GG: Really?

AS: Being a clinically depressed East Coast Jew whose favorite Sesame Street character is Grover.

GG: Oh, wow. Of course.

AS: I thought it was about me for a minute.

GG: Wow.

AS: Yeah.

GG: Wow. That's so nice to hear. I find that the more specific you get as a writer, the more universal it turns out. I first came across that idea in Emerson's Self-Reliance, where he talked about being really specific in your work, and that's been really helpful in stand-up and in the book, too. And I listen to so many books—I have hundreds in my library on Audible—and I just took it very seriously in terms of recording it. I listened to a lot of memoirs, and in the lead up, I listened to Bono's Surrender, and I re-listened to Springsteen's Born to Run. And it was just really helpful. And another one that I really loved was the memoir Tig Notaro did on Audible and listened to that. It was just really helpful to know what I wanted to sound like and just kind of the limitations, but also how you're able to sort of make it into a performance, and it was really cool. I was really grateful I got that opportunity.

AS: Yeah, I was actually curious how narrating it felt, 'cause it's different from stand-up in that you don't have an audience to perform for. So you're not sure if everything's landing, I imagine.

GG: Right.

AS: After doing stand-up for so many years, you're so used to that back and forth that I would imagine that being in a quiet room like the one I'm in and telling a joke and having no reaction feels a little bit… It goes against your senses, I imagine.

GG: Yeah, it was very interesting. I would sometimes see the engineer and the director laughing at things that I had said, so that was kind of helpful, but I couldn't hear it, so I couldn't do anything really in terms of timing. But I do think that sort of in the way a drummer knows the rhythm of their drumming, I feel I have a rhythm in my comedy and just in jokes in general and the pauses. Or, sometimes, it's a matter of saying it faster… or slower, or louder. And it was really helpful.

"I think I have an unusual memory, because I sometimes think of myself as sort of a Wikipedia for my friends' youth."

It was more along the lines of an acting experience than it was really a stand-up experience, because you had to provide a lot of your own emotion and ideas, although the director, Caitlin Davies, was amazing in getting really authentic sentences out of me. It was really a great experience.

AS: Yeah, it comes out great. The narration is great, and as a fan of your stand-up, the nucleus of what it is you do as a performer definitely comes through.

GG: Wow. That's really great to hear, because you're the first person I've talked to who's listened to it.

AS: Oh? Yeah, I'm so glad that the narration experience was great, because it comes through.

GG: Oh, good.

AS: But on the writing itself… How different was your approach to writing this long-form work—I think the audio's 10 hours, so it's not short—compared to writing like an hour long special? I was curious what your approach was like and especially because, like I mentioned before, The Great Depresh—which I couldn't recommend more to anybody, it's an incredible special—correct me if I'm wrong, but it feels almost like a companion piece to that special. I was wondering if that was maybe the impetus to write this memoir, or if they were happening at the same time, or you felt you had more to say?

GG: That's a great question. I think it was an impetus in a number of ways, originally just because the success of The Great Depresh allowed me to have people interested in making a book with me. So, I had enough notoriety or (laughs) a small amount of fame that people were interested in talking to me about whether I had an idea for a book. And I happened to have this idea that I came up with in 2015, and then I got really sick, and I shelved it.

So, when publishers and editors came to me asking if I had any book ideas, I had this proposal, an outline, and a sample chapter that I had actually put together with the help of the comedian and actress and author, Jacquelyn Novak. She helped me do the setup of the outline, and mostly, she just encouraged me to do it. I had that, so that was the impetus in pitching this book idea, which originally was titled K Through 12, and then we changed it to Misfit, because it just was a better title.

And I look at the book, and I didn't intentionally do this, but it almost comes off as a prequel to The Great Depresh in that it tells you how I got to the point where I was hospitalized and very sick, in that my worldview and sort of the events of my early life kind of put in me this depressive nature.

And then, the other part of it is that The Great Depresh is filmed after I've recovered, and this book—the interstitials between each chapter that are about kindergarten through 12th grade—is about the time I was convalescing, after I'd been hospitalized, in my mom's house, the very house I grew up in. So, I was put back in this place… I was 47 years old, and I was reflecting on my childhood in the place that my childhood, geographically and emotionally, occurred. So, it was almost this ironic, or maybe even inevitable, thing that I returned to my childhood home. And because a lot of the people still lived in my hometown and a lot of the locations were intersecting with my life during 2017 when I moved back in with my mom, it seemed to me to be a very compelling through line for the book to kind of have it make sense why I'm thinking about these things that happened at that time—40 years ago in some cases. So, just the illness that I suffer from is really the impetus of The Great Depresh, and in many ways, the book.

AS: Yeah. I was, pretty immediately, so blown away by your memory and how much you recall.

GG: Oh.

AS: Like, you remember specific times—like the time of day when something happened in like first grade. I was curious whether or not that happened, if that's just how your memory always is, or if being home brought back so much that maybe you had forgotten or had kind of drifted away but came back so much more clear when you walked past your old school or something.

GG: Oh, definitely. I was able to make it clearer and more specific and real. When I started to feel better, I started jogging, and I would jog by the elementary school, and it hasn't changed hardly at all, so I was able to sort of reinforce these memories and corroborate my own memory in that. Sometimes, your memory is either fuzzy or inaccurate, so I was able to corroborate a lot of the things.

But also, I think I have an unusual memory, because I sometimes think of myself as sort of a Wikipedia for my friends' youth. They'll call me sometimes, "Who did we have for this grade?" Or, "What did this person say?" There were specific events that they'll call me to corroborate or expound on.

"I've been telling a lot of people that even if it's just for themselves, it can be helpful to write down a memoir and write out these stories. I think it's very therapeutic."

And the other thing is that I've been telling some of these stories for 35 years, so it wasn't a matter of remembering them from their original. It was sort of remembering how I've told them over the years, and then, frequently, I would call friends and corroborate certain aspects and components of the story. So, I was careful to do the best I could to be fair, accurate, and honest in the descriptions.

AS: Yeah, that's tricky. I've heard before that every time we rethink of a memory, we're rethinking of the last time we remembered it, so it becomes like a Russian doll of what actually happened.

GG: Yes. Yes, I think it's why Rashomon… everybody identifies with that, with those types of things, and why it's become sort of a story that's been adapted. I remember they used to do it in '70s sitcoms frequently, and it's so universal and so intriguing and compelling.

AS: Now, this is the part of the interview where I make it a little bit about myself. I've been going to therapy for almost four years now, and I relate to how much emotional excavation takes place in trying to get to the bottom of a mental illness and being depressed. I've spent a ton of time going through my past and my childhood, but sometimes I struggle with wondering whether or not I'm maybe going overboard and connecting dots that actually don't connect. And, I was curious when, in putting together this book, since it's such detailed memory, if that was something you came up against, like getting really deep into a memory and then maybe, I don't know, questioning whether or not an incident was just an incident?

GG: I'm not really qualified as a therapist, but I just think, as a human and a person who's experienced, I think these things that are significant enough for us to remember and hold onto, I think they have some impact. I can't say the weight of them, but I definitely think that. For instance, there are two first grades in the book, and I know that repeating the first grade at my father's insistence, I still always have to make it clear that I was a really good student, and I was in the top reading group, but that whole experience of repeating the first grade was undermining.

I've also brought it to my therapist—I don't know if you ever do that, where you bring incidents to your therapist—and my therapist has said, "Yes, it's very undermining, and it made you insecure, and it was very harmful." Luckily, while my father was alive, I was able to bring up some of these things—it was partly thanks to therapy that I was bringing it up and saying that it was significant enough to be upset about—and my father apologized. He was really good at that. He was really good at owning up to things and having empathy and compassion. He was really a beautiful person who made this one mistake about having me repeat the first grade, but he meant well. And then he apologized, because I told him that it really upset me. I also happen to have a really bad experience with the teacher the second time through and a library book that went missing.

AS: Yeah. (laughs)

GG: So, yeah. I think one helpful thing... I've been telling a lot of people that even if it's just for themselves, it can be helpful to write down a memoir and write out these stories. I think it's very therapeutic. I also think any type of creativity is therapeutic and edifying and improves our brains. But also, it's a great companion piece to modern therapy, where you can bring in these things that either you have thought about a lot over the years, or you haven't thought about a lot over the years, maybe you repressed.

I never had a problem with repression. I have a problem with ruminating and dwelling. So, that's very helpful to bring these things up with my therapist. Some of these stories would make me very sad and emotional, and then I would bring them to therapy, and I would, without exception, feel better about them after I had discussed it with my therapist. It was really helpful. I can't tell people how to do their therapy (laughs), but I thought it was a helpful exercise.

AS: Yeah. It is a great feeling. It's very validating when your therapist tells you you’re right.

GG: Yes. (laughs)

AS: And, you're like, I won this session. Yes, I knew it.

GG: Yeah. I always want to say, okay, I'm not crazy, and then I remember that I am kinda crazy. But, in this instance, I am not crazy.

AS: I'm crazy, but I'm correct.

GG: Exactly. I'm crazy, but I'm correct.

AS: Yeah. (laughs)

GG: So good.

AS: In The Great Depresh, the special is almost structured similarly to the memoir in that there are like these interludes.

GG: Yeah.

AS: For those listening who haven't seen it, it's an hour-long stand-up special that, again, I highly recommend to everybody, and throughout, in between bits, we see footage of you—at your mother's house or at home here in New York with your wife, Sade, or, at comedy clubs talking to fellow comedians—and in one of those scenes, you and the great comedian Bobby Kelly are talking about therapy. And depression, and this myth or this misguided notion, that I think you hear about across all disciplines, that it's beneficial to suffer for your art and for your work, and getting help takes away from it. But you guys talk about how you disagree with that and how, if anything, it's helped you with your comedy. So, I'm curious how you think your comedy has changed since 2017 or 2015, since you really got into facing your depression and your illness head on.

GG: Yeah, I love talking about this, because it's a really dangerous myth. I think that you need to have some stumbles, you need to have some pain, you need to have some depression, not clinical, but to be sad, to be down, to be listless, but even if you are healthy, you get enough of that if you're paying attention to create from it and talk about it and have empathy for people.

I think that it may have been beneficial in that it made me an authority in it in that I could talk about being depressed for extended lengths of time and also that I have a diagnosis and a hospital stay. These experiences make it possible for me to share stories and make people feel less alone. But the experience did not make me a better comedian—it made me to the point where I didn't believe I could be a comedian. The voice that depression attacks you with tells you you're worthless and that you should quit. And not only that—you should probably think about killing yourself. So, that is not a fountain of creative energy. It works against it.

I'm just going to list some things, and I'm bragging, but I also think it is really good evidence that being healthy as an artist is better than being depressed and sick. From 2015 till 2017 and 10 months—because this started, I would say, in January of 2015 or maybe March of 2015, and I started to feel better in October of 2017—during that time, I wrote 10 minutes of jokes, and you can see five of them on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, and that was the extent of my writing. I was unable to write. I was unable to read. I was pretty much catatonic on the couch for nearly two-and-a-half years. My wife thought I was dying. Everybody thought I was finished.

"The romanticism and the mythology of either being in the throes of addiction or depression, or any other kind of mental illness—I think it's harmful and, more importantly, or just as importantly, it's inaccurate."

Okay, I start feeling better in October of 2017. Since then, I've written four hours of material. I've put out one special, The Great Depresh; just re-filmed the second special, called Born on Third Base, tentatively; and now, I'm touring with a new special eventually of an hour-and-a-half of material. I was very careful not to do anything from my act in the book ... I don't want people to feel like they paid for something twice. I don't know if you've ever been burned by a comedian who typed up their act and bound it. It drives me insane. It's the laziest and most obnoxious, arrogant thing I think a comedian can do.

So, what am I saying? I've created nearly five hours of material and wrote a book in the six or five-and-a-half years I've been healthy. It's just so clear that it's much better to be healthy. The romanticism and the mythology of either being in the throes of addiction or depression, or any other kind of mental illness—I think it's harmful and, more importantly, or just as importantly, it's inaccurate.

AS: Yeah, that's really exciting. I'm excited for the new special. I remember I saw you talking about it on [Late Night with] Seth Myers when you were doing it live, so I'm excited to see it.

GG: Yeah.

AS: I'm excited to see it when that comes out.

GG: Thanks.

AS: So to continue on the mental health front, I was curious, what do you do these days that helps you maintain that level of mental wellness? If you're willing to share.

GG: Oh, yeah. One thing that's been mentally helpful—and this is always the area where some people tune out, especially if they're depressed—is when I talk about exercise. Because the last thing you want to do when you're depressed is exercise. And I remember thinking to myself, "Well, the one good thing about this depression is that I don't have to exercise." I was too tired and fatigued all the time, so I didn't exercise. But, what I started to do, and I remember the time in October where I downloaded an Audible book by Oliver Sachs called Gratitude, and it was a half hour, and I said, "Okay. During this book, this 30-minute book, whenever the street sign, the light, says ‘walk,’ I'll jog until the hand comes up, and then I'll walk. And then, when I get another light that says ‘walk,’ I'll jog."

So, I wound up jogging probably a total of 10 minutes and walking the rest of it. Whatever it was, I remember feeling so much better and accomplished, and I also realized that it was the only having to do it for maybe a minute or so, sometimes, that made it possible, because it's so hard to overcome inertia when you're depressed. So, I made the pie so much smaller in that I would frequently set a timer for five minutes to either write or clean up the bedroom, or whatever it was. I would only have to do it for five minutes. And, invariably, you'll be like, "Well, I can keep going for another five minutes," and then I'll keep going for another five minutes, and before you know it, you've made a real dent into your to-do list.

It works really well with exercise, because at least if you walk five minutes, you'll have to walk another five minutes to get back, so now you've got 10 minutes, and it's just so helpful slowly. And then, it gets to the point where you're able to do it longer and faster, and it just really builds on itself. So, I think it's one of those things that even beyond medication or some of the other treatments I use, like electroconvulsive therapy, exercise has been so helpful in maintaining [my mental health] and sometimes getting me out of a rough patch during the day. I always ask myself, "Have I exercised today? Have I talked to anybody?" That’s really helpful… to just spend some time to make some plans, go for a walk, or talk to somebody on the phone. That's incredibly helpful. I always have my wife to spend time with, but if I'm on the road, I always make sure that I have either another comedian, or sometimes I'll accept a lunch invitation from an audience member or a person who works at the comedy club.

So, those are two of the main things. I also take medication, and I don't drink or do any drugs. And I cut down on sugar, 'cause I found that that can destabilize my mood sometimes if I overdo it with sweets. I can feel kind of that… sugar blues, I think people call it. So, there are a lot of things, and I try to share the things that have worked with me whenever I can. And also, of course, weekly therapy appointments are really helpful as well, and so, in combination, all those things have enabled me to have now coming up on six years of really excellent health. I'm not just squeaking by as I did even in my best times—I was sorta eking out an existence. Now I'm really thriving, and I'm really grateful.

AS: That's amazing to hear. And, I completely agree about exercise. I don't know that I ever finished a workout and been in a bad mood after.

GG: Yeah.

AS: You're setting tangible goals for yourself—whether it's just running a mile or lifting this or whatever, and then doing it—and it slowly builds up over time a confidence that you are the person that you say you are, or the person that you want to be. And, yeah, exercise, I think, it's a tactile way to do that.

GG: Totally.

AS: Completely agree. Towards the end of the book—I think you're directing it towards the listener and the reader—you say something along the lines of, "If you're feeling badly about yourself, just remember that you're still the little kid that the bus driver was happy to see every day." I was very moved by that, and I thought that was really great. I was wondering, as the author, what you would want listeners to take away from Misfit?

GG: I think that line really resonated with me, too, when I wrote it. I remember welling up, because when you write a book, you also have to read that book a lot. That's what you don't think about. I've read every page probably 100 times, and I would go months without reading certain chapters because I had moved on, and then I would have to come back to edit and copy edit, and things like that. So, when I wrote that last chapter in which I talked about remembering being the child that the bus driver was happy to see, I had re-read the chapter where the bus driver was happy to see me every morning. And when you finish a book that takes you through so many years, and now you're in your present, it makes you realize a lot of my circumstances have changed, my physicality has changed, but I'm really that same person who, before a lot of things undid it, liked himself, looked forward to going to school, was very happy, and felt loved by almost all the adults in his community.

And so, I think that's one of the things that I would want people to get back in touch with is that their childhood made them who they are, and it is important to reflect on it and take forward some of the lessons you learned about learning, which is everything you're able to do now without thinking about, that you at first struggled with, from tying your shoes to reading to, for me, making a basket. These things were all difficult, and it is a great lesson, and almost a mantra that I've adopted, which is, "I'll figure it out." I've figured out everything up to this time. I've figured out how to be a good basketball player. I've figured out how to be a good husband. I figured out how to be a good comedian. Why will this thing that I'm struggling with right now be the thing that undoes me? Whether it's setting up the printer or getting the new television to work—these things should not undo me if they sometimes cause anxiety or stress. Say, there'll be a new job. When I got cast on Amy Schumer's show Life & Beth, I was nervous going into it, and I forgot to tell myself, "You figured things out before that were more daunting, so you'll figure this out."

"I've figured out everything up to this time... Why will this thing that I'm struggling with right now be the thing that undoes me?"

I think that's a really good lesson. And I also think that I want people to get from this book to be a little bit more compassionate and kinder to each other and see how it just affects everyone, how you're treated and how you're treating people, and also, as sort of a salutation to teachers and books, reading. It’s played such an important part in my life, in my health, and the idea that people are reading any book makes me happy, but the idea that they'll be reading my book—it's literally a dream come true. This is something I've thought about… one thing that’s interesting in the book is that I talk about a book, the first book I ever really wrote was in second grade, called The Lonely Tree, which was just this blatant allegory for a very, very lonely, sensitive boy. And so, this is really the culmination of an aspiration that I began in second grade at seven or eight years old.

AS: Yeah. I remember, actually in The Great Depresh, when you're with your mom and you're talking about that book. And you're like, "Look how obvious it was." And your mom was like, "What are you talking about?"

GG: Yeah. (laughs)

AS I related to that so much, having a Jewish mom, too, just kind of being like, "Well, you were fine." And just being like, "No, I wasn't."

GG: Right. Yeah.

AS: And, you know, I gotta say I myself hit a low point in my depression, towards the end of 2020. By that time, I had actually, before that, seen The Great Depresh and had really loved it and resonated with it. But having that exist in the world already at the time in which I was going through what I was going through, it was really special and important to me that there was this body of work that was funny, but also it gave me an ability to articulate certain things and to relate to it. And I think also, when I had first seen it, I watched it with my mom, and so when I was, like a year later, going through my hard times, it was a good reference point, almost to be like, "Hey, Mom, remember in that special? That’s kind of what this is like right now." It was a really nice reference point to have for myself when I was going through it.

GG: Wow.

AS: So, just as a fan, I appreciate the special and appreciate your work.

GG: Oh, well, that makes me really happy, because I will say that one of the most difficult things about depression is that it is so hard to describe to people who haven't experienced it. The English language fails us just in the term depression. It's the same word we use to describe how we feel when the Yankees lose.

AS: Exactly.

GG: Or, as well as how we feel when we don't think there's any purpose to our life. We're so limited, and the one thing I wanted to get across is how it feels. And up until the night I shot it, and then when we added the documentary, I still hoped and was concerned with, "Is this going to make people understand what it feels like?" And to hear people who have shared it with spouses and family members and friends to explain how they're feeling, that has made me so happy, and it's so gratifying. But I also think there are a lot of other pieces of art that have done a good job with that. I read Darkness Visible by William Styron. It's very short, and it's a great book about his experience with depression. And I think Maria Bamford and Chris Gethard have done such a great job in talking about their mental illness. And then, I read a short story by David Foster Wallace a couple of weeks ago called “The Depressed Person.” It's a story in Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, and it talks about [how] one of the most frustrating and maddening aspects of depression is being unable to describe how you feel to people. And that was so moving, and he gets it right, man. Of course, David Foster Wallace suffered from depression and ultimately died from it, so he happened to be a person who understood it but also was an excellent writer—problematic but very good at the craft.

AS: Yeah, David Foster Wallace, and all of those people you mentioned.

GG: Yeah.

AS: Maria Bamford's new book, too, is great. Yeah.

GG: Yes.

AS: So, you've mentioned your love for audiobooks throughout the interview, and you even mention it in your book. I'm just curious if you're listening to anything right now that you would recommend to the listeners?

GG: Yeah. I think audiobooks were really helpful when I was particularly anxious, because it got my mind off my worries and so I would listen to them. And also, it made me feel like I was doing something. And also, they were really helpful companions for any of the exercising I was doing. I just finished Touré's Nothing Compares 2 U, which is an oral history of Prince, and it was riveting and so well performed and so smart and fascinating. And right now, I'm in the middle of two books. My wife and I are listening to Neil Gaiman's The Graveyard Book—we read the book, and now we're listening to it because the performances are astonishing. It's so good. And then, I'm listening to Randy Rainbow's Playing with Myself, which is really funny, and he's such a funny, interesting guy with a similar background in that he grew up Jewish and artistic and sensitive, and it really resonates with me. I just really like it. So, that's what I've been listening to.

AS: Yeah, those are all great picks, and some Audible editor favorites, actually, too.

GG: Yeah.

AS: Right on. Yeah. Well, great. Gary, thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me today.

GG: Oh, this was a great interview. It was my pleasure. Thank you so much for being so prepared and asking me such great questions.

AS: Oh, thank you. And listeners, you can get Misfit by Gary Gulman on Audible.

GG: It's credit worthy.

AS: It is. It's 100% credit worthy. (laughing)