I’ve been DMT-curious ever since my octogenarian father made psychedelics his pandemic hobby, culminating with a life-changing trip on the stuff, courtesy of the psychoactive secretions of the Sonoran Desert toad.

Whether harvested from a frog or brewed in ayahuasca, the so-called “God molecule” is common yet strangely complex to activate. It’s really more of a drug technology, according to the scientist Andrew R. Gallimore, author of Death by Astonishment, a mind-bending, science-stuffed history of DMT. Even odder? DMT trips often involve elaborately detailed visions of busy insectoid aliens, xapiri (spirits that inhabit the Amazon rainforest), and elves, which Gallimore distinguishes from mere hallucinations and even psychic archetypes. What he speculates they are is the real trip.

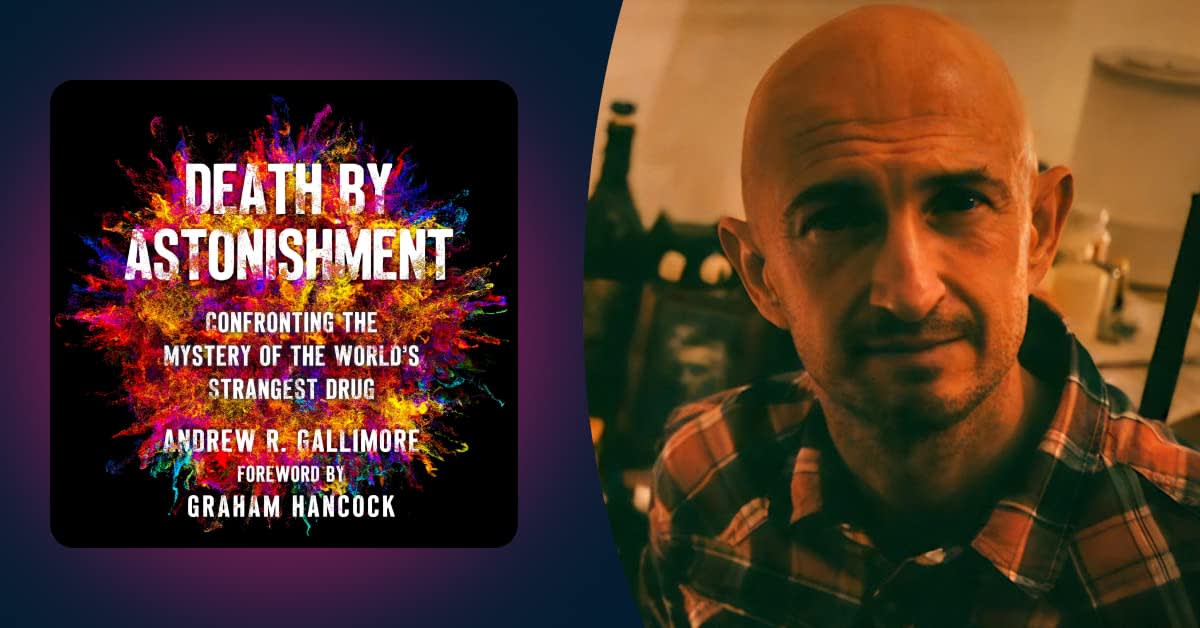

Populated by counterculture icons such as Terence McKenna, who inspired the title, and with a foreword by Graham Hancock, Death by Astonishment will thrill psychonauts and anyone interested in the mysteries of consciousness. It further ignited my curiosity about this strangest of psychedelics, so I was thrilled to talk to Gallimore about the ideas, experiences, and ramifications behind the book.

Kat Johnson: Congratulations on the new book, it's fascinating, and I'm currently having my mind blown by it as I write this! Can you share what drew you to focus on psychedelics in your career, and then DMT more specifically?

Andrew R. Gallimore: When I was very young—seven or eight—my thing was ghosts, werewolves, vampires, and the paranormal. So, I guess it wasn’t such a surprise that, as I entered high school, my interests started to shift toward unusual states of consciousness—and psychedelics are certainly the most efficient way to achieve these. But DMT, in particular, doesn’t merely generate an unusual state of consciousness but arguably the strangest state of consciousness a human can experience. After my own experience with DMT, I knew that I wanted to spend my life trying to understand and make sense of it.

You seem fun at parties, and I mean that totally sincerely. How do you describe your work and this book to casual acquaintances, and what kinds of reactions do you tend to get?

How I describe my work depends somewhat on whom I’m speaking to. I rarely get straight to the alien intelligence thing. Instead, I’ll start by explaining that I study the neuroscience of psychedelics. If I get a positive response—which is most of the time—I’ll progress to DMT and, eventually, to the idea of using the molecule as a technology for communication with advanced discarnate intelligences. Most people are surprisingly open to these ideas once I explain them, and they realize I’m not totally crazy.

Let's get to the weirdness. Your decades of research suggest that entities such as insectoid aliens, "machine elves," xapiri, jesters, and the like are common visions in DMT trips. Even as psychedelics have become more mainstream, the idea that alien intelligence—which might be fabricating our very reality—is revealing itself to us via the drug "technology" of DMT is wild stuff! As a computational neurobiologist, pharmacologist, and chemist, what kinds of scientific rigor did you apply to this theory and was there anything that especially turned you toward thinking it might be true?

I always describe my work as about 80 percent deconstructing and analyzing—using neuroscience—more orthodox explanations for the effects of DMT and showing why they fail to explain them. It’s in that remaining 20 percent that I work to develop the alternative explanations, including the idea that DMT allows us to interface with some kind of intelligent agent—this is the approach I use in Death by Astonishment. I certainly didn’t leap to this conclusion but, in fact, feel that I was forced to reach it.

We can now explain how, in the presence of psychedelics, the old familiar world begins to break down, becomes more fluid and unstable, less predictable and more novel. We can even explain how and why certain types of imagery—drawn from personal memory or influenced by inherited archetypal patterns, as well as from spontaneous emergent patterns of brain activity—tend to present themselves to a tripper.

But when the normal waking world is not only obliterated but replaced in its entirety with one that bears no relationship to the world left behind; when the brain somehow begins constructing worlds it has no business constructing, worlds populated by hyper-intelligent, non-human, discarnate entities with no referent in the normal waking world; highly coherent, more real than real, higher-dimensional worlds of crystalline clarity and impossible narrative and structural complexity that not only don’t exist in normal waking life, but could not exist… Well, then, we have a problem.

I've noticed two distinct approaches to psychedelic scholarship: to take psychedelics oneself, to add an informed empirical perspective to the research, or to eschew them, to legitimize one's work among mainstream scientists and academics. What is your approach and why?

It really depends on the type of research. There’s a kind of impassable gulf between the reports of people who have taken DMT and the immensity of the felt experience, which can never be fully transmitted in words. So I think it’s important to have had at least some experience with DMT to be able to engage with the phenomenology. When academic scientists refer to encounters with advanced intelligent alien beings as “illusory social events,” I can only imagine someone with absolutely no personal experience with DMT ever saying something so obviously silly to anyone who has.

On the other hand, if your work focuses only on therapeutic properties or the fundamental molecular pharmacology of psychedelics, then personal experience (at least spoken about publicly) seems less important. Fortunately, I left the academic world several years ago to focus on writing, so I’m lucky not to have to worry about what my academic peers might think of my use of psychedelics. I’m free to say and write what I like—and I exercise that freedom.

Counterculture heavyweights such as Terence McKenna, William S. Burroughs, Aldous Huxley, and Timothy Leary all show up in Death by Astonishment, as do contemporaries like Rick Strassman and Graham Hancock, who provides the introduction. To the extent that there is a contemporary movement of intellectual and scientific psychonauts, what are you guys buzzing about these days? How would you distinguish your work from the pack? And what book or books do you think fans of Death by Astonishment should turn to next?

One of the major aims of Death by Astonishment is to convince people that DMT represents a true mystery—that science struggled to make sense of its effects for the better part of a century and is still struggling. From Burroughs to Leary to McKenna to Strassman, everyone who takes DMT is left shocked and aghast by the experience. While McKenna and Strassman, in particular, seemed to take seriously the possibility that DMT granted us access to some kind of intelligent Other, few others in the scientific community really took that idea seriously. In all of my work, I try to keep one foot firmly planted in the scientific arena whilst reaching into territory other scientists fear to go.

"From Burroughs to Leary to McKenna to Strassman, everyone who takes DMT is left shocked and aghast by the experience."

I hope that my work in Death by Astonishment will convince at least a few of those scientists that what I’m proposing isn’t so crazy—that DMT might well allow us to establish and maintain communicative relationships with beings far older, far more intelligent and advanced than humans. I can’t think of anything more worthy of getting buzzed about than that. Anyone who’s excited by these ideas should definitely check out Terence McKenna’s books, especially True Hallucinations. And, of course, Rick Strassman’s DMT: The Spirit Molecule is essential for anyone interested in the experiences of his volunteers injected with DMT during his pioneering study in the 1990s.

If your theory on DMT is true, what do you think it means for humanity? What assumptions do you think it upends and could it heal us from some of the most traumatic divisions and problems currently facing us?

Accepting that there are probably intelligences vastly more advanced and capable than us out there in the cosmos is one thing. But accepting that such intelligences are right here, right now—and can be reached and communicated with by anybody willing to fill their lungs with one of the most common molecules in the natural world—is another thing entirely.

It’s profoundly humbling to realize that, not only are we not at the top of the tree when it comes to intelligence and technological advancement, but we barely register on such a scale. It certainly puts our endless quarrels and power games into perspective, but what we make of this realization only time—and perhaps not a lot of it—will tell.

For folks who might be rushing out to have their own DMT encounters after listening to your book, what advice do you have?

Don’t underestimate this molecule. When Terence McKenna said that the only real risk in taking DMT is “death by astonishment,” he was only being slightly hyperbolic. If astonishment could kill, DMT would be lethal. Fortunately, DMT is remarkably benign physiologically, but obviously anyone with a weak constitution (high blood pressure, heart conditions, etc.) should tread carefully. Expect everything you thought you knew about the nature of reality and of our place within it to be obliterated. Think carefully about whether you’re ready for that.