Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

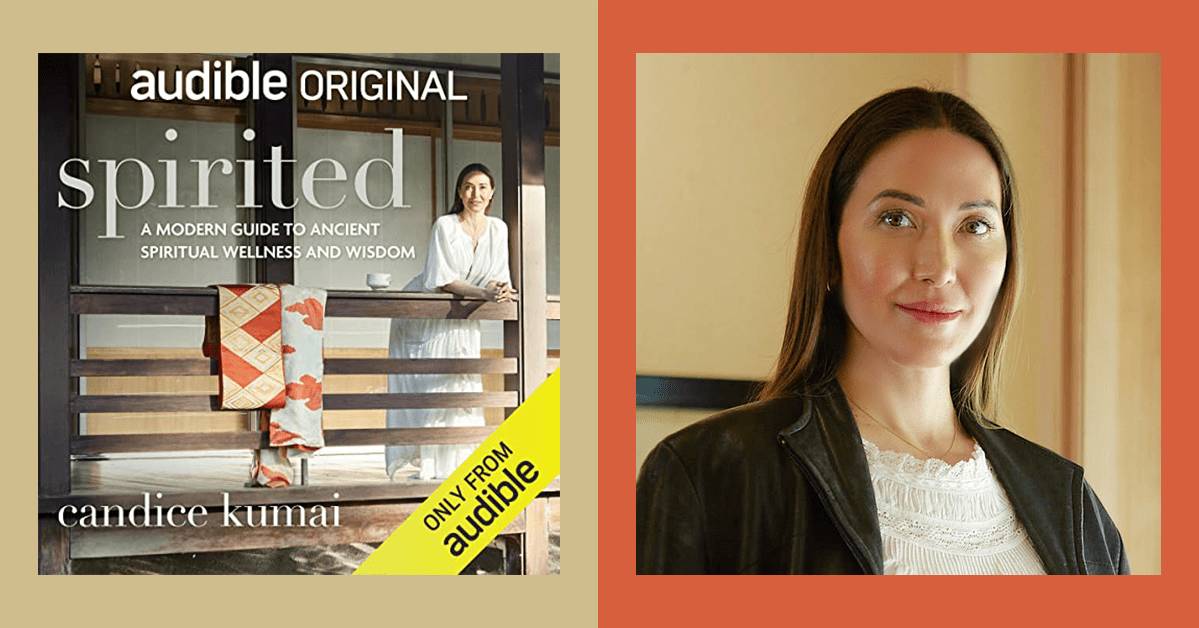

Rachael Xerri: Hello, I'm Audible Editor Rachael Xerri and I'm here today with author and wellness icon Candice Kumai to talk about her new Audible Original, Spirited: A Modern Guide to Ancient Spiritual Wellness and Wisdom. Candice also hosts the weekly top-ranked podcast Wabi Sabi and has written previous books as well, which you can also find on Audible. Welcome, Candice.

CK: Thank you, Rachael. Thank you so much for having me.

RX: Oh, thank you for being here. Firstly, let's talk about how Spirited is a departure from your earlier works. You say in the audiobook that this is the most vulnerable you've ever been. What inspired you to write Spirited and what made you want to share your story now?

CK: It was actually a very natural progression in the writing and the history of my books. It wasn't like I woke up one day and said, "My next book is going to be on spiritual wellness.” It was more like I lived down the street from here, in North Williamsburg in Brooklyn, and I had nowhere else to go but home to my parents and to figure my shit out and to straighten out my life. And I had started to think that I wasn't even well myself. I was never happy or fulfilled, regardless of the image that I may have portrayed for all of these years. I had spent a lot of time traveling through Japan, trying to figure out my ancestry with my mother's roots there, and also learning more about my father's history of lineage in Poland. And I didn't know the full story of my own Polish grandfather, who fought against the Germans and the Russians, becoming a POW very quickly and having to escape from the Russians on his own.

It took a tremendous amount of time to write this Audible book, but it felt just so truly right to take off all these layers and my own mask and stop talking about matcha and miso and start talking about my mental health, anxiety, depression, all the men that I dated, all of the drugs that I did, all of the partying and the sort of numbing out of being this golden girl of wellness, which is what I was touted for so many years in New York, and letting everybody else around me know, "You're okay and I'm okay and not one of us will get through this life without suffering.” It's like our one common denominator. As much as we love laughter and food, we will all suffer.

So, I really found out that I had not learned a lot about my own Buddhist heritage. I was raised Catholic, in a Christian church, and then we always went to visit the monks in the mountains when I was a little kid, but I didn't really grasp the concept of the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. And then I had said to myself, "There is no modern zeitgeist for young entrepreneurial women like you or I. And how can I explain to people, 'Yeah, I might like a cocktail, a margarita, a Japanese whiskey, or traveling to virtually go drink the best matcha in the world, but I also really want to tap into the side of me that has never been exposed, that wants to know more about the afterlife, or this life, and that wants to know more about how to be a better spiritual practitioner.’”

"You're okay and I'm okay and not one of us will get through this life without suffering. It's like our one common denominator. As much as we love laughter and food, we will all suffer."

I had seen that I was so dark inside, and I have seen the darkness become so normalized. And if somebody doesn't speak out and share a little bit of a slice of life that maybe somebody could relate to, I just said, "You know, if I can write six cookbooks by the time I turned 36, I could probably write a spiritual wellness book and just take a stab at it and see how it turns out."

RX: Thank you, that was great, there was so much to mine from that. In your introduction, you make a distinction between spirituality and religion and that one can have spiritual practices outside of religious affiliation. This is a unique concept and I'm sure it's one that will really resonate with many people. I know it resonated with me. What audience did you have in mind while you were writing Spirited and who do you think can benefit from this listen?

CK: I wanted to tap into every girl and guy and person and individual that maybe felt like their identity wasn't who they necessarily were. It was important to know that, at this point, everybody has a whole plethora of different friends from different backgrounds, heritage, culture, tradition—and that includes religion and spirituality. And you can judge people all you want on the things that they believe and the values that they carry and the practices that they hold true, but you have to understand that everybody has a different belief system and your beliefs are not universal. And if they were, this world of billions of people would be very odd. We're not a homogenous culture and we never will be. And until people realize that there are others out there, and whether you believe in the same things as them or not and whether you agree with the things they believe in or you don't believe in the things that they believe in, it doesn't really matter at the end of the day because you can still learn to see another's perspective.

I just said, "I'm just going to write from my heart and know that my experiences are not shared by everyone," but I do hope, much like, say, Trevor Noah's work, it's okay for me to talk about growing up as a mixed kid and what that might have been like and how painful and cutting it was sometimes, and how not fun it was to not have a pure identity. But also how beautiful it is that my mother loved my father enough that she did not believe in the same things as him, and at the end of the day, none of it even mattered, except that they loved one another.

RX: Yeah, so speaking of your identity and some of the feelings around it, I know early on in your book, you talk about how you felt ostracized in school as one of the only kids who was Asian and mixed race in your class and this was a real challenge for you growing up. And what struck me is, in your first visit to Japan with your family, you talk about how you felt connected both to the spiritual practice but also to a community. And now, of course, you've made several trips back to Japan on pilgrimages and to visit. How has your connection to Japan and Japanese spiritual practices evolved over time for you?

CK: Oh, so, so beautifully, Rachael, although not perfect because there were so many flaws, especially in me and the trajectory of my life. I can vividly remember not being allowed to go to my grandpa's funeral in Japan. My mom blamed it on my finals when I was in college, but I really just think she's embarrassed of me because I was a party girl. And I do go deeply into the pain of having an Asian mother and how beautifully painful it can be at times.

The most difficult part in my work when it comes to working with Japanese and Japanese Americans: I've had to prove myself tenfold over any Western white man and his work. Why haven't the Japanese allowed Japanese Americans or mixed Japanese individuals to feel, number one, that we belong there? And number two, why not allow those of us who are mixed to share with our own population of people? So that would be, "Could you let me share about Japan with my own audience in the US?" And there were many beautiful Western publishers that allowed me to do so, but some of the hardest stuff I've had to come up against was Japanese people, and it still is, not understanding my work.

I feel that it is time for people to allow other voices, and especially for the older generations and populations of Japan to appreciate those of us who don't look like white men, who are sharing our own heritage. And even if my friends in Japan are Pakistani and Japanese and they're mixed, they are Japanese. If they're Brazilian and Japanese, and they're mixed, they're Japanese and you should still treat them with the utmost respect. A lot of us get passed on as just half in that culture and it has been very difficult, but I do see the light and the changes. It's changing, but it is taking time.

So, although my relationship with Japan has always been so special and beautiful and cherished with just gold in my eyes and mind, it's not all fun. A lot of this comes with a deep, profound responsibility of actually retelling from a different perspective so that people can see it's not just about traveling there and exploiting the culture for your Instagram or TikTok. There are so many stories, like the Nagasaki survivors I interview when I go to Hiroshima or Okinawa or visit the museums. I've seen plenty of individuals who survived war, famine, the atomic bomb. There are a lot of stories that don't get told because they're not shiny and new and popular and cool, but I think my job is to take some of the darkest parts of life and give them a little bit of light. And that way, the contrast makes the good times and the light times that much more special.

RX: Thank you for sharing that, so intimate, and you have many of those intimate moments throughout your book that we're going to talk about in just a little bit. But to focus on the light a little bit, one of the many aha moments from your Original that resonated with me is this idea, and I'm going to quote your book, that your “whole life's purpose in this lifetime is spiritual evolution.” Can you expand on that and what it's meant to you?

CK: Yes, so when we go back to the question of “Why did I make a right turn or a hard left again from the wellness sector and food and cooking,” they say the first part of your life is for the body and then let the second part of your life be about the spirit. There's a lot of debauchery and partying and confusion and growing into who you are, not knowing who you are, playing around, doing things that you can do when you're young. And then when you get old, there's the spirit and there's the enlightenment and there's the suffering. And there is, hopefully, because not everybody wakes up to this—and I'm not perfect and I'm not always the most mindful—but there are a lot of people that don't ever come to the realization of mindfulness or living in a way where they can simply ask another, "How are you doing?" and they genuinely mean it. And I ask people to question, "What do you believe in? Why do you care what others think so much? Would you like for things to be a different way?" I would too, but unfortunately or fortunately, they are what they are, it is how it is, and therefore, we must learn to live in harmony with what we've got.

I don't know what triggered this awareness. I think it was gradual for me. There's still times where I miss my old life and I miss the partying and going out. And then there are times where I'm like, "I definitely like my pajamas, my bed, my pillows, my partner, and my cat way more than going out." So, there's this beautiful, profound growth process. I started writing the book at 38 and now I'm almost 41, so it took a couple of years for me to really get this out there. It had felt very much, like I had mentioned before, that we needed a zeitgeist for modern day times. To be modern and technologically advanced and to have had so much change so rapidly over the last 20 years and to not have spirituality or the wellness sector in religion and spirituality necessarily catch up to the current time.

Because I had grown up in a household with multiple religions, backgrounds, and belief systems, I felt like I could use that source. I could look at how my Polish family accepted the Japanese family, and vice versa. And virtually nobody else between the immediate two sides had been in an interracial marriage. And my parents seem to be like best friends at Costco every weekend. And I was like, "How does that work?" And they have a beautiful relationship. And although not perfect, it was enough for me to say, "I've got it. I got the Japanese grandpa who was an impressionist artist on one side, who loved alcohol, and the POW grandpa of Polish descent on the other side who lived through a grimacing time of darkness.”

And boy, does that lineage live through your bones. And it will come and bleed out into the pages that you are writing and there is no other way that I can describe it other than I think sometimes your ancestors send you a lot of notes, and you have to either choose to listen when you get to that point in your life when you can feel it. And I don't necessarily want to say that they're your spirit guides, but they're certainly a large part. If they paved the way for you and they paid the ultimate price through war and famine, hardship, then you absolutely can live a beautiful life with honor and truth and dignity, and we should be doing better at this point, and so that is why I wrote the book.

RX: I love that. Another helpful idea that you introduced in your book is mono no aware, or accepting things as they are. And I wanted to talk about what are some ways that this has helped you on your journey and that you think mono no aware can help others.

CK: Oh, Rachael, you really did good research. Mono no aware pertains to the pathos in life in Japanese, the notion that everything will not be perfect and it will not be okay all the time and that there is a darkness to life that is normal and we can all live through it because it will teach us so much. My life is not perfect at all, and that's another reason why I had to start with Kintsugi Wellness, my last book; [it] was a gradual process into Spirited, the current Audible Original. So it took a lot of bravery to write really ugly parts of my life on paper, and there's still so much to share.

I think it's good to share with our young female entrepreneurs, and men too, and anyone who's suffering that sometimes you're going to get a phone call, an email, a text that you don't resonate with, whether it's a job loss, a breakup. And I do want to remind everybody it is best to be kind to everyone because you do not know what people are going through behind closed doors. And there are friends of mine that have been so beautiful and graceful about the loss of a loved one, a marital affair, cancer diagnosis, the loss of a job maybe that they really wanted. And the disservice that we do to each other nowadays, and I'm included in this, is that we show the beauty of our lives and not mono no aware, the pathos. So, I've also experienced suicide and seeing that hit close to home through extended family. It's very, very dark and it needs to be talked about because if we don't normalize the mental health issues in this culture, I think we will all regret not bringing it and putting it out on the table. So, as much as I want to talk about fun things and Japan being goofy and weird and kawaii, I can't because everyone talks about those things. To talk about the darkness is very brave and it's harder to do.

"I think my job is to take some of the darkest parts of life and give them a little bit of light. And that way, the contrast makes the good times and the light times that much more special."

I think it's cool to see shows, most recently, like Beef come out and talk about how angry the Asians—we’re angry people and we don't talk about it. Not all of us, but a lot of us. And I've seen it with my own friends and my own family, including myself. I thought it was my dad's side of the family, but the more I see Asians being honest about our infuriation of so much, like being overlooked, being underpaid, underserved, etcetera, and we can't talk about it. And it doesn't mean that we're not extremely grateful for where we've gotten so far in this life. We're all different, but as a whole, everyone can be angry, depressed, upset, anxious, and everyone can be a better listener, where you listen to understand someone and nod and you don't listen to give a response. And so the best way I can say to love on mono no aware is to know that it comes and it goes and your life would not be full of beautiful brilliant colors without the dark.

RX: I want to dive a little deeper into mental health and some of what you were just touching on. So, in Spirited, you talk about how important a psychiatrist and therapy has been during your healing process. How does taking care of your mental health factor into your spiritual wellness and vice versa for you?

CK: Wow, Rachael, it was hard to admit that I needed a lot of help. And like I said, I've just dipped my toe in the truth pool of “this is who I really am,” and there's so much more. And while I haven't been able to process all of it, because a lot of it I buried somewhere very deep and dark inside of me for many years, and I've never faced some of the nastiest and worst demons, things that started from like junior high and high school. But I knew that I had an addiction to sleeping pills, and I specifically mean prescription ones. And I would drink on them and I would get high on them. And I didn't even know, because as far as I knew, I was an idiot thinking, "Well, these are just prescriptions. I can't get high off this."

And I should have known better and I started to see a serious psychiatrist. And he was right here in New York, and I'd like to say that he saved my life by helping me professionally, to remind me that one day I might never wake up, and what would my mother do, and I had to change my life from that day on. I didn't really have a choice because I love my mom more than anything. I think there are a lot of people out there that probably have the same problems as I did. And they may not even realize it, because they're drinking on Xanax or they're drinking on antidepressants and it's a pretty bad cocktail to be taking every day.

So, talking to someone, it was nice to be able to at least have someone listen and not always respond. They just listen to understand. And then it was even better to have the doctors that were very brave that said, "I need you to consider talking to your medical doctor about no longer being on these because they don't work for you." And I think everybody should get the best medical advice from their own therapists, psychiatrists, psychologists, doctors, etcetera, because I'm not a medical professional, I'm a writer just sharing my story. Like I said, it's just dipping my toe in and also, like, a tiny little slice of my life, but I knew sharing just that little bit might save a life and it was the right thing to do instead of acting like I just drank and smoked weed like everyone else.

Sometimes I don't even regret it because I think it taught me a lot of lessons and it made me who I am. And I do believe that a lot of us need to go through what I call your own Kintsugi process, which means, when you're at your lowest of lows and you're completely broken, you have to do self-work to put yourself together, and you should never do it alone. You should absolutely reach out to the professional. I believe the suicide hotline is 988 and you can just dial 988 anytime you need to talk to anybody and not be afraid to reach out because it's confidential and it will do you good.

RX: Thank you, Candice. And yeah, I can confirm that number. I just did a quick fact check. Thank you for being so vulnerable, too, and for sharing your story. I think that every time we share our mental health journey, we help to destigmatize mental health. So, I want to talk about another phrase that you repeat often in your audiobook Spirited. Bochi, bochi, ganbatte, “slow, slow, doing your best.” What are some ways that we can practice this concept in our everyday life?

CK: Oh, yeah, a monk that I loved, Suzuki-san, he's a monk in the mountains of Shikoku Island in Japan and part of an 88-temple pilgrimage, which is one of the most beautiful places in the world in my opinion. He taught me that it's not just about doing your best. Ganbatte in Japanese, as we say, it's about being slow and doing little by little and not overwhelming yourself with this world of like, "I want to make the 20 under 20, 30 under 30, 40 under 40 list. I need to hustle. Everyone else is ahead of me." No, you don't. You don't have to do any of that. You can live a very simple life as my sister does in London working at her own bike shop, or you can live a very extravagant life, as a friend of mine who owns a penthouse, a partner at a legal firm in New York. But you can also just do you and not worry.

I think we worry so much about trends, what other people are doing. We are highly involved in other people's lives to the point where it is not even necessary nor is it good. And you do not have to keep up with anyone. That is a myth that we tell ourselves. It is an outdated societal norm. You don't even have to be on social media. You don't have to have an account. You don't have to have a website. You don't have to have a newsletter. You can virtually live in the woods, in the mountains of Oregon or Washington state, or go get a shack in Hawaii or Maui or Kauai or Lanai and just live.

I mean, it's really simple, if you think about it. It's very scary for a lot of us to think about because we want a lot of structure to our lives, but I think if we choose to take a little break it will take you out of the headspace that you're in. And I do want to remind people, you just do not have to do what other people are doing. It is imperative that you learn that early on, because I was only able to pursue my dreams as a writer in New York because I followed that: “Do your best, a little by little.” You do not need to do what everyone else is doing.

RX: So, you've touched a bit on how important your relationship to your parents is specifically. I know as many daughters do, we struggle with wanting acceptance from our moms. And you have one particularly tear-jerking moment in your audiobook towards the end. It's when you return back to California and you ask your mom, "Did I make it?" What was it like in that moment for you hearing her validation that she thought that you had.

CK: I mean, I can get teary just thinking of it now. I feel like it could be written in a sitcom or a show one day. I'll never forget how not only did I ask her that, but I also thought I was a failure because I had had to move out of New York for a while. And I know immigrant kids will be able to resonate with that. You know, your mom and dad, there are some parents that really coddle their kids and they want them to come home, but fortunately or unfortunately, my parents were never that way. My father had put limitations on how long I was actually allowed to stay when I would take breaks from rent in the city because I just wanted to drop all my stuff at their house and go to Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Europe, Africa. I just wanted to get away.

I had felt like my mom cared about my cat, Sisi, more than me that day that we arrived, because that's just how Japanese mothers love. She's also very funny, so she's kind of like playfully, "Oh, I just want to see Sisi. How is Sisi?” She had really doubted me at the beginning of my career in food and writing. And I think a lot of kids will resonate with that when you choose to go into the arts. It's difficult. It will never be easy. The arts is a questionable place. And then years later, we were shooting a show for Shiseido and my mom came to set to shoot with me, which she'd only done two other times in my entire life. She's not the kind of person that wants to be in front of the camera. She's not thirsty. She doesn't care about fame or beauty. She cares about education, cats and dogs, and being a good person, and her Japanese cartoons. So, we shot with her and then my mom had mentioned randomly how proud she was of me. And my friend Meredith, she actually cried super hard when we were putting all the wardrobe away at the end of the shoot day together. And I was like, "What's wrong?" and she said, "Well, I know how badly and deeply you needed to hear what your mother said."

"It's okay because not everyone is going to love you and like your work. And that's normal."

It's almost like your friends can take one for you. Like, when my friend Dana's brother passed away, I just wailed for her right here in Brooklyn, even though she was all the way in Hawaii Kai in Oahu. So, when you find profound connections with others, especially your girlfriends, you don't want to lose the essence, especially if you become a well-known artist. It becomes more and more difficult through the years to be humbled and to stay normal. But they can watch the trajectory of your career and let you know if you've made it, but they can also just as easily keep you in check like my mom does.

So, I still don't know if she thinks I'm a success or a failure. It is TBD. Currently, I'm back in the mode of feeling like, you know, loser mode. I know that sounds really crazy, but any artists will understand what I mean. It's like you're done with a project and you're promoting it, and although I am wildly grateful for all of my opportunities and work, including especially this project with Audible, I can't explain it other than being a granddaughter of an impressionist painter who arguably never made it. You know, he didn't make it big. He had his pieces at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Art and the OPAM among others, but it was actually my aunt Kyoko Kumai that was at the MoMA and all over the world who is much more of a success on paper.

So, The Artist's Way by Julia Cameron, a great book, a great, profound book with lots of practice to go through the lulls and the highs and the lows with. But I do think having a Japanese mom means you might be on a trajectory of having to succeed your entire life and just living for her in a weird way. She helps to keep my pencil sharp and I wouldn't do anything less than the very best that I can do because of her standards.

RX: Thank you for being so vulnerable, and I was getting a little choked up as well, as the daughter and granddaughter of immigrants and having been told not to pursue English as a major when I was in college or to pursue writing or editing as a career. That really did resonate with me. So, I very much appreciate your honesty and truth. Were there any times when you were recording Spirited where hearing your story aloud, hearing yourself perform your story aloud, that you were perhaps able to look back on times in your life when you were struggling with more grace?

CK: Well, it's interesting that you bring that up because I had never thought I would talk about my former partner in LA [who] was an opioid addict and an alcoholic, and I was only 22, 23, 24 when I was with him. And that's one of those stories that I buried somewhere far away, some of the things I actually forgot, like the painful things. I think Rose, my lovely editor at Audible, had allowed me to just be myself and she loved me just how I came. I didn't have to change anything for her. And it was so interesting to me because I kept saying to her, "Are you sure you want to leave this cursing in?" Like numerous times, I had asked Sarah and Rose, I was like, "The cursing," and you know, they were okay with it and I thought, "Wow, times have changed."

Another thing that came up for me was that people were exhausted with the voices that are in spirituality right now. We had seen and heard a lot of the same old and it had not become new and fresh and revealing. When I read Trevor Noah's book, Born a Crime, I was very happy that a mixed kid was sharing his story. Because although my story's not like Trevor's in any way, his experience growing up in apartheid, in a horrible time in South Africa, but having a white father and a South African mother—or his father, I believe, is Swiss. I resonated with that. You know, my dad's entire family is European and they are the furthest away from Japan, and yet they collided worlds and it was a beautiful story. So I think I was able, for the first time in my life, to be proud of being a mixed kid and where I came from, instead of feeling ashamed, embarrassed, ugly.

I mean these are things that most immigrant children will always feel because we don't look like everyone else. And I think the difference also is that Trevor grew up in South Africa and we grew up in the US. And in the US, I think people are very blind to seeing how bad children get bullied and teased and made fun of for the way we look, for what we eat, for what our last name looks like. I mean, I grew up with a Polish last name and I looked Japanese and I got made fun of so bad for it, and those are things that don't leave you in life. It almost is kind of like I feel maybe liberated and able to share it now in hopes that a lot of people can understand what that's like.

But I also can understand that not everybody is going to resonate with this book. And I could be the most graceful person in the world talking about the ugliest parts and they may not get it. And my mom had always told me, “It's okay because not everyone is going to love you and like your work. And that's normal.” I'm able to write from a perspective where I think immigrant kids and kids of different backgrounds hopefully will be able to see that this was a little difficult to write and it wasn't for any other reason other than to just share so we can connect.

RX: Absolutely. There are so many concepts, practices, ideas, amazing moments, vulnerable moments in your audiobook. If you had to settle on one takeaway that you would like listeners to walk away with, what do you hope resonates most?

CK: I mean, you're right, it's hard to find one that sticks out. I think, overall, for people to know that we will all suffer in our lifetime and no two people will have the same suffering, and so it is always possible to be kind and that you never know what anyone is going through. So it is best to just be kind to others. And I hope that simple phrase in itself is enough. And maybe the last thing I'll leave everyone with is, if we all have the self-realization that we're all, as Ram Dass says, just walking each other home, then it kind of just puts things into a very simple snippet, like different things at different times.

RX: Thank you, Candice. That's a beautiful way for us to end. If you're listening to this interview, please go and download Candice Kumai's audiobook Spirited. Give it a listen. It's absolutely worth it. Thank you.

CK: Thank you, Rachael.