Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

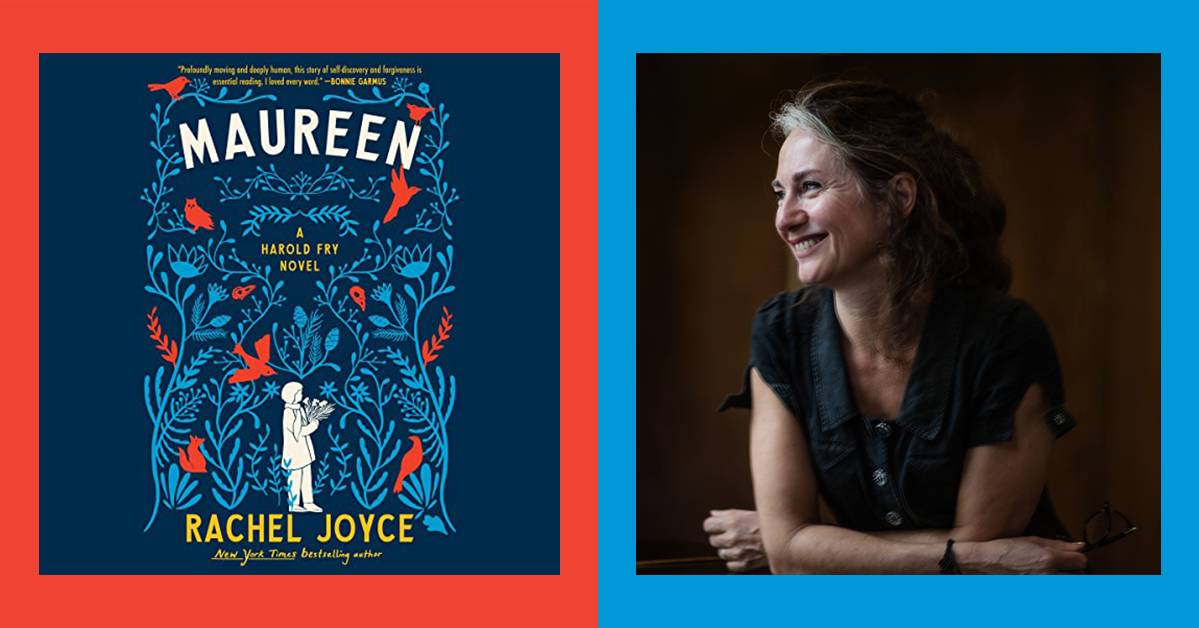

Emily Cox: Hi, I'm Emily, an editor here at Audible, and I'm so thrilled to be speaking to one of my absolute favorite writers, Rachel Joyce—the author of The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry, Perfect, The Music Shop, among others—about her newest book, Maureen. Welcome, Rachel.

Rachel Joyce: Thank you. It's so nice to be here.

EC: It's so nice to have you. Thanks so much. I wanted to actually talk to you a little bit about some of the things that you wrote in your prologue, which I thought was so interesting and just really added a lot of color to this trilogy. You said that you hadn't thought that Harold's story was a trilogy at first, and it was a reader who suggested to you that it absolutely had to be. Can you tell me about that experience?

RJ: Yes. It was very early on. So, it was just after The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry had come out and I was doing a kind of book event, and that was when this reader came up to me and said, "You do know that it's a tryptic, don't you?" Which kind of floored me. And I think at the time, I thought, "Oh, no," because I'd only just got to the end of the first book. I just didn't really think I could do it all over again. But as with readers, they're often right, and she kind of saw what I'd sort of seen but had turned my back on, and that was that there was Queenie's story and that there also needed to be Maureen's story at some point. And Queenie's story I found very easy to find. It became the second in the trilogy, which is The Love Song of Miss Queenie Hennessy. But the third part, for lots of reasons, I really stalled on, and it's taken me a very, very long time to get here, and it's taken me a lot of thought. But I did know that it wouldn't be complete without it.

EC: Right. Maureen is such a presence in both of the other stories. You sort of described her story as a sticky closet that you were hesitating to open. What finally propelled you to get in there and tell Maureen's story?

RJ: Actually, I have been trying to open it for years, and every time I opened it the wrong things fell out, I would say. I've actually written four versions of this book, and I don't just mean the beginning, I mean the whole thing. And each time I've got to the end and thought, "That's not it. I haven't found it." So I've had to discard it and get on with whatever else it was I was doing. I think it's partly because she's a tricky character. She's not like Harold, who, I mean, not everybody loves Harold, but despite his quietness he has a sort of openness and an extrovert quality, whereas Maureen is, she's much tighter and she's much more, she's shy, really, but she's much more guarded. And she has a tendency to say the wrong things. So she was a much trickier character to kind of fight to negotiate.

But also, because her story is so much about the kind of passing through grief to something else, and the whole trilogy of the books I think has been about my working out my process of grief with my dad, I was never really ready until very recently to think about kind of facing that last—I don't know that it's the last stage, because I think it's always there with you—but a kind of essential stage of letting go.

EC: Right. I did want to ask you about that. This trilogy is so centered on grief. But a lot of your stories are. There are elements of it I see in some of the others. And is that process of grieving your father—I'm curious how this has become such a central theme to your work.

RJ: I think grief has become a central theme, but I think it probably always was in that I was writing radio drama for years before I started writing novels, and it was kind of present then as well. Sometimes we have a sort of certain tendency and we don't know quite where to put it, and I'm probably, as a person, a bit on the downward inflection [laughs]. You know, I have that in me, and I always try to kind of push the downward inflection to a kind of slightly more “up” place.

"The whole trilogy of the books I think has been about my working out my process of grief with my dad, I was never really ready until very recently to think about kind of facing that last... kind of essential stage of letting go."

But that sort of sense of loss or being on the outside of things or not quite reaching things, I think I've always had that in my personality. But certainly the death of my father did really propel me into writing The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry, because I think I so needed somewhere to put my feelings of that kind of lacerating loss that I was feeling back then.

EC: Yeah, I understand. So, I wanted to go back to what you were saying about having a downward inflection, and it's interesting that you say that because whenever I recommend your stories to people, I'm always saying how there's a surprise and delight element there. I always say, "Well, her characters are always finding—they're always surprised by someone and surprised by the kindness of strangers." And yet I also think that you have such an amazing way of surprising the reader or the listener. You sort of send us down one path and then there's a bit of a reveal or a curtain pulled back. How do you manage to steer your readers down one path before turning them around?

RJ: Oh, that's such a good question. Well, I do think a lot about storytelling. I think a lot about structure, because I come from this radio drama background. A play on the radio is so easy to turn off. It's so easy to just, if it doesn't interest you, just to walk away from it. And so I think part of my discipline in writing was how do I tell stories that, I mean, not necessarily that have masses of plot thrown in them or loads of action, but how do you seduce the reader? How do you enchant the reader? How do you tease the reader? How do you mystify the reader? How do you change the reader? Those are all things that I think I've thought about in the context of radio drama. So, it's sort of part of how I tell a story, really.

But I do think a lot about those things, and I love being surprised by the writing process, which I constantly am. I mean, I attempt to plot and plan, but I'm a terrible planner. I can give you a really brilliant plotline once I've written the book. But I have to write the book to find out what works. And that means that for me, approaching the story from the outside and saying, "Well, this will happen, this will happen, this will happen because these are what's supposed to happen" doesn't really work for me because it's in the writing it that I get right in there and I work out what the characters would do.

EC: I feel like you talk about your characters as if they come to you. They sort of arrive at your door in some way versus you creating them. And is that part of how you've always written?

RJ: I think it actually is. I mean, without sounding a bit too out there, I do feel that characters—initially, I think Harold Fry had quite a lot of my dad in him, but quite a lot of me, too. My dad, for instance, always wore a jacket and tie. He just always wore a tie. And even when he was in hospital having various operations for his cancer, I remember visiting him and he would be in his jacket and tie—

EC: Oh, wow.

RJ: —sitting next to the bed. I think he just partly couldn't bear us to see him in that state of kind of vulnerability. It's a very kind of British thing. So, that really informed Harold. And also my dad always wore those decking shoes, which always made me laugh because my dad never went anywhere near a boat. He was actually terrified of the sea and couldn't swim. So, it really made me laugh that he had those shoes. You know, that just all became part of Harold.

EC: I love that he wore those for his whole walk and didn't get on with sneakers.

RJ: And there are people who write to me and go, "Why does he not wear boots? I can't bear the fact he doesn't have proper boots." And then I have to say to people, "Well, it's a story and this is a little bit metaphorical." He wears his shoes, that's the whole point. He has to do it his way. He can't do the walk with walking boots because then he would be not being true to himself. Anyway, that's always my answer to the walking boot people.

But Maureen, in terms of characters who kind of arrive, was definitely somebody who kind of marched into my imagination, I would say, and then kind of asked, "Well, what are you going to do about me?"

EC: What I thought was remarkable is how consistent her voice was from the first book to this third book, which is 10 years later.

RJ: Yeah. I mean, she makes me laugh. Her manner does make me laugh, even though it is quite abrasive sometimes. But she has been really, really clear to me and, I mean, it does feel like they have been hanging around for 10 years. The book originally was a very short radio play, so I knew their dialogue even before I wrote the book, and I've then gone on since then to write the screenplay for the film.

EC: Oh, wow.

RJ: Yeah. I really do know them very, very well. In answer to your question about characters turning up, I increasingly think that the writer is just basically a very good therapist, or you try to be. These characters come and they don't really want to change, but they know they have a bit of a problem and they've got something they need to sort out. But they don't really want to have to change anything major. And your job during the process of the story is to kind of help them shift. And it doesn't mean that by the end their lives are perfect, but that they might be a bit better equipped to deal with whatever life throws at them.

EC: Yeah. I love that all of your books end with hopefulness, even though all of them deal with tragedy in some way. I've really loved that about listening to them. You talk about your work writing for radio plays. How did that inform your novel writing? That's obviously interesting to us at Audible. How did you think about how the audiobook would be when you were writing these?

RJ: Well, the audiobook, I was very, very keen for Penelope Wilton to read because she plays Maureen in the film. And I saw her rehearsing. I was lucky enough to see some of the takes. I've seen the film now. And she is so right for Maureen. She is that mix of sharp, very, very funny, and then incredibly vulnerable in moments that you don't expect. She has a sort of slightly offbeat quality. So when we were talking about the audiobook for Maureen, it was just really clear to me that she would be the only person to read it, if she would accept. And I was so thrilled when she said yes. Because it's beautiful, her reading it.

EC It really is.

RJ: I think it's really special. Because I do come from this audible, radio background, I've always been interested in how do I tell a story that people can't see. And with a radio play, obviously, all you have is dialogue. You maybe have a tiny bit of voiceover, but that always felt like cheating to me. In radio drama, you think, how can I create a soundscape, I always called it, that would kind of be like a film? It would be like the shots that you see, but that sound would do that work for you. It's amazing how creative you can be with sound. I mean, I think I was adapting the Brontës and I worked out just how a different bird call, what a difference it made to the scene—that, for instance, a blackbird or a kind of thrush is quite a friendly sound, but a crow is quite ominous. Or peacocks would always suggest something more palatial and aristocratic. If you pay attention to those details, they'll do a lot of work for you, a lot of spade work.

EC: You're going to have to come work for us, I think maybe is what I'm hearing.

RJ: That's fine [laughs].

EC: Now that you mention bird calls, Harold becomes a birder in this third novel. Is that a passion of yours?

RJ: Do you know, I'm really trying to be able to tell the difference between all the birds. And if they've got lots of colors, I can tell. But the little birds that look all the same, I sit here thinking, "What are you? I just do not know what you are." So, I don't think I have the passion for it that Harold has. I mean, certainly when I first wrote The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry, we just moved to where we live now, which is very, very rural, and I'd always known quite a bit about plants, but it was like the beginning of a love affair, and I think a lot of that influenced the book.

"I increasingly think that the writer is just basically a very good therapist."

I was just gobsmacked by the size of the sky where we live, and just seeing how many shades of green there were. I'd just never seen or kind of taken in that there's green that looks like lettuce, and then there's green that looks almost black. And then there was so much to take in, and then to try to find the words to describe that. I think that really, really fed into the first book, so that it feels right that Harold would have moved on now in this very peaceful state that he's in 10 years after the walk, where he's just very interested in what lands in the garden. Whereas Maureen hasn't got the time because she still hasn't done that journey at the beginning of Maureen out of her familiar world, and that's why this book felt so necessary for her.

EC: Right, and gardening for her is such a practical matter, which is why it was so interesting, her contrast with Queenie's garden. Did you always know that Queenie would be a gardener?

RJ: I think I didn't really know that until I got to the second book. And then as soon as I began thinking about it, I thought, “She has a sea garden,” and I didn't even know what a sea garden would be, but I knew that she must have one. And then what happened was that I went to the place where I imagined her garden would be, and in my mind, I'd put her in a little kind of hut, a sort of tin-hut-type house overlooking the sea. And where I'd imagined it, I got there and I thought, "Oh, no, there's no way. This is just completely the wrong place." And then I went walking for about three miles up the coast and I came to a cliff and I could not believe it. On the top of the cliff there were about 20 tin-hut bungalows, chalet-type things. I mean, exactly what I'd imagined. It's just that my imagination was about three miles out.

EC: That's amazing.

RJ: It was amazing.

EC: It feels like a premonition in some way. So interesting.

RJ: Yeah. You know, when you were asking about, are these characters there? I think sometimes there is something there and you're just listening to whatever it is, and then your imagination is meeting it and this kind of rather wonderful outcome seems to happen.

EC: Yeah. You've talked about your radio career, and you were also an actress when you were younger. But I think you published your debut when you were in your 50s, if I've done my math correctly.

RJ: Yeah.

EC: I mean, it is such an achievement that I think a lot of writers who have families and other careers find hugely inspiring. Was becoming a novelist something you always kept your eyes on over the years? Was that a goal? And what was your story to getting that first work out there?

RJ: Yeah, I’d always wanted to write a book. Even when I was a child, I wanted to write a book. I've always, always loved reading, and when I was a child, I felt met by books and contained by books and I kind of traveled with books. So, they were really important to me. But I think it was also writing things down was just how I worked things out and expressed myself.

So, I remember being distraught. This is my ego here, but being distraught about the age of 11 because I realized I'd got to 11 and Daisy Ashford had written The Young Visitors, I mean, maybe she was eight? I don't know. But I realized that I'd got to the age where somebody had published a book, or written a book that was published, and I hadn't done it. I seriously wrote my autobiography when I was eight.

EC: Oh, wow.

RJ: Because I felt that the world hadn't recognized my poetry, of which there was not much, in fairness [laughs]. But I did write about how brilliant my poetry was. So, I mean, I'm being really tongue-in-cheek, but it is true. It was always something I wanted to do and it was part of how I expressed myself. And I continued to write. Even when I was acting, I was always writing. But I think it took a very long time to be in a place where I kind of found what my voice was in fiction. And it's such an elusive thing. It's sort of very hard to describe, but I think when you get to a stage where you think, "Oh, yeah, this is me on the page. I'm being true to something now. I'm not trying to be anything else or anybody else." It took me a very, very long time to get there.

EC: Yeah. And you have a family. Finding time to write among having a career and raising a family—I've asked this question to several other authors, actually. I'm just curious how you sort of carved out that time for yourself and for your own goals.

RJ: I think I recognized that it was something that was so important to me that I wasn't going to let it go. And I think I became a bit driven by it anyway. So, what I used to do when the children were little, and it's still my best writing time, is to get up. I'm a naturally very early riser, but I would get up about 5:00, and I loved writing in the very early mornings. I mean, partly because my children, I knew, were safe, but unconscious [laughs]. And also just because I find dawn such a kind of clear but inspiring—it's such a hopeful time of day, when you write and the light comes. It's so very basic. And sunrises are spectacular. I often say to my husband, "You missed it. It just didn't look like the normal day." So, everything about that time really, really works for me, and that was definitely how I kind of got into writing. I mean, I would always be driving my children somewhere or other, and in the end, we had a pad of Post-it notes, and whoever was sitting next to me in the passenger seat, I would just say, "Oh, look, I've just thought of something. Does Harold drink?" And then they would have to write down "Does Harold drink?" And stick the note on the dashboard for me so that I wouldn't forget.

EC: I love that.

RJ: That's how I got through.

EC: That's an amazing piece of advice. Well, what are you embarking on next now that this trilogy has come to a close? Are these characters going to appear elsewhere?

RJ: I did feel that I've, well, I was about to say I've finished writing about them, but I'm actually lying. So, I'll explain. In terms of the books, yes, I knew when I got to the end of Maureen that I had healed Maureen in so far as I could, but also that the book rounded off Harold's story and Queenie's story. I knew that there was a couple of, they weren't loose ends, but they were things I hadn't opened. And so when I got to the end of Maureen, I did think, "Right, that's it. My job is done." But there is the film coming out in the UK in April, and I'm not sure yet when it will be more widely available. So the characters are still with me and it's quite strange seeing characters that you've had in your head suddenly on a huge screen. It's sort of like looking inside your head, and it's quite unsettling, I've found, and almost a little embarrassing as well. It won't be a shock, but the film coming out will be a bit strange. And then I'm also, I mean, insanely, working on a musical of Harold Fry.

EC: A musical. Oh, wow.

RJ: Yeah. A musical. I'm not writing music. I can't even sing. But I'm sort of writing the script. And again, it's just going back to that drama part of my life, and, actually, I'm so used to now kind of being alone at my desk and writing what comes up or what I see. But it's years since I've been in a rehearsal room. And for many years that was just part of the way I worked. So, I'm really looking forward to kind of working in a collaborative way again.

EC: Oh, great. So, you'll be able to sort of help in the production aspect of it as well.

RJ: Yeah. Well, I'll be there during the whole thing, because I've written it, but what I won't be doing is singing.

EC: Right [laughs]. You know, I'm realizing there was one question I didn't get to that I wanted to make sure I asked, which was I was so intrigued by the moment in Maureen where she talks about the author and she goes to the reading and she sort of tells this author off for being a tourist, which I thought was just so funny. I mean, funny, sad, heartbreaking, but I felt like I just knew immediately what she meant. This author had written about a middle-aged woman losing her son to suicide and yet she herself was in her 20s. So, there's no way that she had experienced this kind of loss. And the author's quite contrite, which I think Maureen appreciates, but also feels bad about. Were you exploring an anxiety that you've experienced as a writer? I was just curious where that came from, because I thought it was so interesting as a writer to work that in.

RJ: Yeah. I was interested to work it in because obviously there is so much discussion at the moment about what it is fitting to write and what it is not fitting to write. I have a lot of sympathy with the argument, the debate, and I'm very interested in it. Though I also feel that as a writer, you must try—I mean, as a reader you must, and as a person you must, but certainly a writer—to keep trying to understand what you don't know. You must keep trying to make those imaginative leaps.

But the honest truth is that when Harold Fry came out, I had had an experience of somebody close who'd lost a child to suicide. So, it had informed the book. But it wasn't my own loss and I don't for a moment pretend to—you know, I would try to understand, but what they were bearing, I've never had to bear. But I did do an event where a woman, I mean, I did several events where people said to me, "How could you give Queenie that cancer? That was abhorrent what you did." And I had to say, "I'm really sorry, but that was my dad's cancer. That was what I saw and I couldn't fudge that because that's what my dad went through and that's the truth." But for a lot of people, it was unpalatable. And I was then apologetic, and then they were apologetic because they'd asked the question, and it was a difficult, you know, it was the sort of, it was thorny. But because it was so thorny, I did think it's interesting to kind of go back there and revisit it and look at what's going on.

It did feel right that Maureen, being the person she is, if she'd read that book, would certainly at the beginning of her story would be furious with that book and would express it and would actually make a fool of herself and cause embarrassment all round, you know? And nothing would be healed, and that the writer, being a young woman as she is in this particular instance, would be kind of so thrown. What Maureen does is sort of brutal and unpleasant and leaves everybody feeling messy.

EC: Right. Right. But she is a ball of fury. That is such her character.

RJ: She is. Yep.

EC: And so it's such a great way of capturing it.

RJ: And I know you're not supposed to say that you love your characters. It's sort of a bit like, you know, "I really love my writing when I say this." But I do love that Maureen at the end is kind of still not prepared to read that book. She's kind of like, with the author's new book, she kind of wants her to have another new book, and she wants her to be a big, big bestseller, but she's never going to read her.

EC: Right. She's like, "It's not for me."

Well, Rachel, thank you so much for joining us today. I can't tell you how much I've appreciated this conversation. I can't wait to see this movie. I hope it comes to the States soon. I'm going to be in England in the summer, so if it's not here by that time, I'll check it out when I'm over there.

RJ: Well, thank you so much. It's been such a pleasure.

EC: And listeners, you can get Maureen and the rest of the Harold Fry trilogy now on Audible.