Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

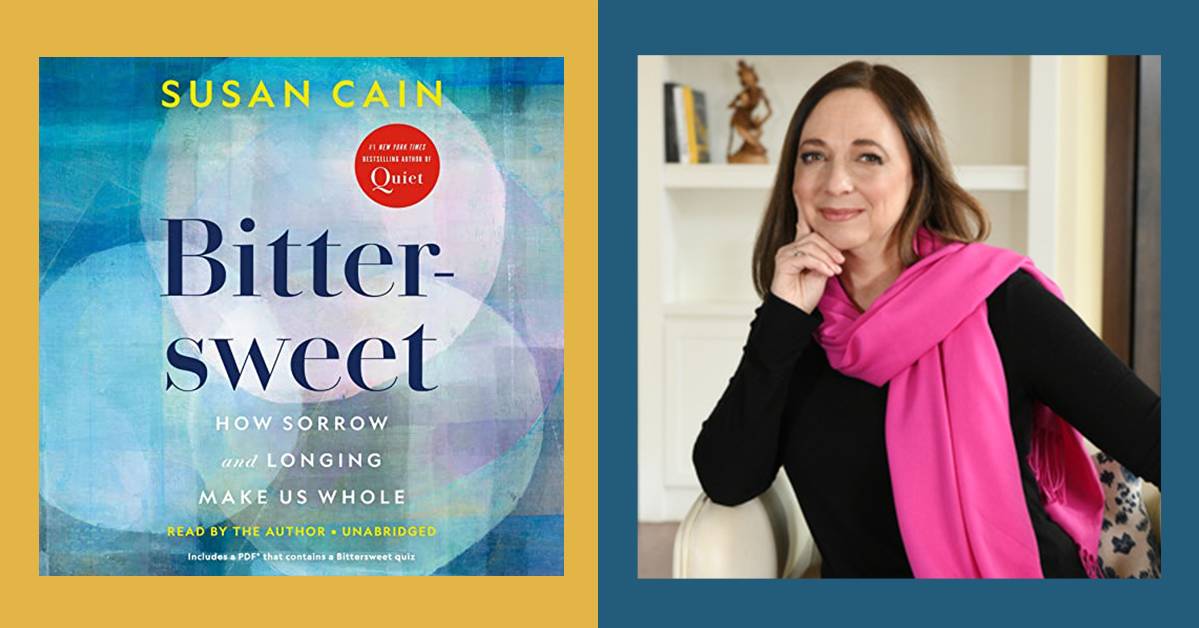

Christina Harcar: Hello. I'm Audible Editor Christina Harcar, and I have the pleasure today of speaking with Susan Cain, best-selling author of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can't Stop Talking, about her new title, Bittersweet: How Sorrow and Longing Make Us Whole. Welcome, Susan.

Susan Cain: Thank you so much, Christina. It's so great to be here with you.

CH: Let’s dive in, because I am listening to this audio and I love it. I love how meditative and thoughtful it is, and how thought-provoking. Susan, how would you summarize Bittersweet?

SC: This book is the result of a five-year quest to grasp the power of a bittersweet and even melancholic way of being. What I had learned is that the bittersweet tradition is centuries old, and that we really are creatures born to transform pain into beauty. And this is a message we don't often hear, because we're not even really allowed to talk about melancholia or pain. Those kinds of things are frowned upon or seen as distasteful to discuss in everyday life. But, in shutting ourselves off from that side of discourse, we are also depriving ourselves of centuries of wisdom that comes to us from our artists, writers, and wisdom traditions. And, even more recently, from psychology and neuroscience too. I looked at it all.

CH: Thank you. That is a much better summary than I could've done.

SC: This was actually an incredibly difficult book to summarize, and it took me a really long time even to come up with what I just said to you. I think the nature of the book is it's talking about ineffable experience that we all have. And we can get into that, but the book begins with effability in a way.

CH: Yes, absolutely. Let's start with the dissonance and truth of compunctio.

SC: Oh gosh, I love that you asked about that. I have an epigraph at the beginning of the book that talks about the concept of compunctio, which means “the holy pain.” It was something that Gregory the Great talked about in the year 540, so a long time ago. He is talking about the grief that we all feel sometimes when, as he puts it, "When we're faced with that which is most beautiful." He says, "The bittersweet experience stems from human homelessness in an imperfect world." And I really ask people to look at that. If you think about those moments we all have, when we tear up at a beautiful TV commercial, or a waterfall or painting, whatever it is, why do those things bring us to tears?

"We really are creatures born to transform pain into beauty."

The question I first asked myself is, why do I feel so tearfully uplifted when I hear beautiful sad music? What I've come to understand is that what we're really experiencing is the desire that all humans have for a more perfect and beautiful world. And when we see intense beauty, we're getting a glimpse of that world, and it's reminding us of the gap between the world that we live in and the one that we believe we should be living in, the one from which we were banished. For some people, this takes the form of an explicitly religious impulse, so this is really the heart of all the worlds' religions. And for some of us it takes the form of appreciation. Appreciation is a very mild word, but it’s an intense reaction to music, nature, art, or beauty.

But for all of us, this is one of the most important experiences we ever have, because it is the source code of our creativity and of our ability to connect with each other. And I say “connect” because we're all in a sense united in this strange sense of exile from the world as we wish it were. And the sorrow that we feel at not being in that world is the ultimate shared human experience. We're not aware enough of it to be able to make the most of that sorrow, to use it to connect. But it really is the source of some of our greatest sense of union with each other.

CH: Yes. I think what you just shared is the beating heart of what I loved about this audio. We're in a business about connection through listening, and the idea that what we call sadness can be the mothership of that connection was strangely comforting and very exciting to me.

SC: Why exciting?

CH: Well, one quote from early in the audio that really stuck with me—although, I have a whole list of ways it gets reframed throughout—was, "longing is momentum in disguise." You are talking about the gifts of bittersweetness, and I think one of them is that bittersweetness can be an engine for personal fulfillment in this counterintuitive way.

SC: Yeah, absolutely. Follow your longing where it's telling you to go. The etymology of the word "longing" literally means to grow longer. It means to reach for something. That really is the heart of the creative impulse. For example, you want to bring into being something that didn't exist before, because the thing that you're going to bring into being comes from that other place that we all long for, or is a representation of it. You see this in our entire literary heritage, from all over the world. But I'll give you an example, one that everybody knows.

Homer’s The Odyssey: we think of that as a poem of epic adventure, and it is, but that's not what starts it. What starts the poem is that Odysseus is weeping on a beach, longing with homesickness for his native Ithaca. There's an ancient Greek concept called pothos. Pothos meant the desire for an unattainable, beauteous, or perfect thing. And it was understood that this state of longing was the natural catalyst for the adventure that was to come, but there would've been no adventure without the pothos being there first. And that's true for all of us. If we could tap into that, we would understand the longing. I'll give you an example in my own life of how following my longing led to the right place.

It's a bit of a long story, but I write in the book about how I used to be a corporate lawyer, and I was the most unlikely Wall Street lawyer on earth. But there I was, and I was kind of ambitious, as I wanted to make partner. I was working 16-hour days for seven years. And then, on this one day, a senior partner comes into my office and tells me that I'm not making partner after all.

At first I have the sense of the world kind of crashing down around me, but I leave the firm that very afternoon, and a few weeks after that I decide to end a seven-year relationship that I'd been in that always felt wrong. And so, now I'm kind of floating around in the world without a career anymore and without love and without a place to live, because I had left the apartment that I'd been living in with this person for the last seven years.

I fell into a relationship with a guy who wasn't fully available for various reasons, but it was a really intense connection. I became quickly obsessed with him in a way that I had never been before or since. He was a musician, and a lyricist, and had a big, expansive, lit-up kind of way of being. Being in the grips of those obsessions is like intense pleasure, but also intense pain, you know? This was the age before we had cellphones, so I was living in New York City and I was spending my days dodging into internet cafes just to see if there had been an email from him. I would walk a block and then go up to the café to look, check my email, walk another block, find another café, check my email. We've all been there.

CH: Yes, my Gen X friend, we have.

SC: So, I had a friend, Naomi, and I was regaling her with, I'm sure, long, boring, exacerbating stories about this guy. And then one day she looked at me and she said, "You know, you wouldn't be this obsessed if he didn't represent something that you're longing for. What does he represent? What are you longing for?"

And the minute she said that, I knew the answer: that he represented the world of art that I had wanted to be a part of. I wanted to be a writer since I was four years old and he represented all that. It was like, he was an emissary from that perfect and beautiful world. And as soon as I understood that—I know this sounds far-fetched, but it's true—the obsession fell away. I still loved him, but I was no longer obsessed and it was no longer erotic and it was done. I turned to writing, which is what I had wanted to do for all those years. And I have never looked back since.

CH: Wow.

SC: So I say to people what Naomi said to me: "What are you longing for and what does it mean to you?"

CH: Wow. That's a very powerful story and it makes me fond of your former object of obsession, because in a way, that's what an angel is. It's a messenger about something ephemeral.

SC: Me too. I think of him as an angel who came into my life for that moment. Yeah, absolutely.

CH: So now you're a writer, and a great one in my opinion. What was your favorite part of Bittersweet to write? What part made you the happiest to get down?

SC: It was just so amazing to be living in the bittersweet tradition for this last five, six, seven years that I've been writing this book. That meant, for me, listening to that kind of music and I got really interested in the poetry of Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī, the 12th century Sufi poet—who I believe right now is the best-selling poet in the US. Who would've thought? Which is kind of amazing.

Living in this world has been incredible. One of the things that the bittersweet tradition teaches you is the intense importance of beauty and all that it represents. So I've really oriented my life that way to the point that I now begin every workday by finding a favorite piece of art and sharing it on social media, paired along with a quote, or a poem, or an idea that I thought went well with the painting. It was just this practice that I started doing and it just kind of happened. It's amazing because now there's all these kindred spirits on my social channels who love that kind of thing too. And it's like this daily moment of beauty. I've come to really understand the importance of that.

CH: Wow. This is an interview about you, Susan, and yet, I feel completely validated because I was a little shy to tell you that since listening to the audio, I've been living in the bittersweet tradition. You just gave words to how I've been feeling. I want to encourage listeners who are hearing this now to join us in the bittersweet tradition. It really is a very rich broth and a more mindful way of living the life you would be living anyway. But there really is kind of a glamour to life, to be aware of the painfulness of beauty.

SC: Yeah. Thank you for saying that. It's funny, I didn't realize when I wrote this book that it had one big thing in common with Quiet, which is that after Quiet was published, I started to be inundated with emails from people who all used the same word in their emails, and the word was "permission." Like, "Oh, I read this and now feel like I have permission to be my true, quieter self." And I mean, this is early days, but once again, I'm starting to hear the word you just used, "validation." I'm hearing the word "permission."

I believe that many people who feel the richness of the bittersweet tradition don't have words for it and don't feel that it's socially acceptable, even if they had had those words, because you're not supposed to go to a place of melancholy. We don't even have a way of distinguishing between melancholy and depression in clinical psychology. There is no distinction made even though anybody who's experienced this bittersweet state can tell you that they're completely different. I don't know whether it's a difference of degree or a difference in kind. I'm not really sure, but I don't think it matters at the end of the day. There's a state of melancholy that does not lead you to the emotional black hole that is depression, and that is very rich and rewarding. I'd like to resurrect that.

CH: Yes. I hear and deeply appreciate this idea that you just brought into the conversation that bittersweet concepts give everyone the permission to experience our own emotions more fully.

My next question was going to be about Quiet, because I felt like Quiet was a book about the gifts of introversion, even if you're not an introvert. I'm not an introvert and Quiet changed my life. And I feel that Bittersweet can do that too. There's a quiz in the beginning, which I took and scored pretty highly on. But if you are a very sanguine person and you score on the other end of the spectrum of that quiz, there's still enormous gifts about bittersweetness.

So, I wanted to dive into some of them more specifically. I want to invite you to say more about: what might it look like for other people to be living in the bittersweet tradition?

SC: It might be good to take a moment to define what bittersweetness is and then to talk about what some of the gifts are of understanding it and living in it.

CH: Yes.

SC: To my mind, bittersweetness is the recognition that joy and sorrow and light and dark are forever paired. A kind of piercing joy, the beauty of the world, and an awareness of passing time. Our culture basically tells us that the main road of life is when everything is going well, and you have good health, and your job is good and everything. And then, when there's bad health, or when something bad happens, that's like a detour from the main road.

The bittersweet tradition tells us that it's all the main road. The joy and the sorrow, they're both the main road. And that's a completely transformative way of understanding day-to-day experience. It removes a lot of the resistance that we feel when bad things happen. When a bad thing happens there's a kind of "why me?" impulse that we talk about. But if you're looking at things in a bittersweet way, you don't have that reaction as much.

"Bittersweetness is the recognition that joy and sorrow and light and dark are forever paired."

To give an example of how this affects child rearing, for example, we took a family vacation when my kids were very young. I have two boys. We rented a farmhouse that happened to be right next to this field in which lived two donkeys. The boys fell in love with the donkeys and they spent the whole vacation like at the fence feeding the donkeys. The donkeys would come running over when they saw them in the morning and it was this beautiful summer romance. A couple days before it was time to go home, the boys suddenly realized that this trip was coming to an end and they'd have to say goodbye to the donkeys. They started crying themselves to sleep at night. And these are happy kids, but they were really bitterly upset at having to say goodbye.

We told them all the things that parents would say at a moment like that. "Another family will come and they'll feed the donkeys. Maybe we'll be back again and we'll see them again." And nothing really helped until we said, "This is actually part of life, this feeling of saying goodbye. And it'll feel better in time. You'll be able to remember the donkeys and feel happy and you won't always feel the way you do right now. But just know, this is part of life. You felt it before. You'll feel it again. And everybody feels it." And that was the thing that dried their tears.

And I think it's because kids who are growing up in relative comfort are taught the message that that isn't part of life, but they suspect that it is. And having somebody confirm it for them is a huge relief.

CH: Yes.

SC: And it's a relief for all of us.

CH: So, yes. You've hit something. This idea that a person can be what we consider to be fortunate and still have an entire range of feelings about loss, and sadness, and parting, and some elusive happiness that we've been separated from at our origin. Do you think, in this specific moment you and I are speaking at, kind of the end of the pandemic, we hope—do you think that the gifts of bittersweetness can cure what we now call languishing? The feeling of not being quite right and kind of a malaise and crise d’affection for "normal" life?

SC: I do think that understanding life in this way, that joy and sorrow are going to come and they're probably together at every given moment, does help when things like a pandemic happen. And I don't mean to make light of that. I lost my father and my brother in the pandemic. I actually wrote about that in the book.

I struggle a lot and wrestle a lot with the question of, to what extent anyone can ever truly accept the impermanence of this world? As much as you might use a Buddhist practice that is focused on impermanence, or a Stoic practice, memento mori, you know, "remember that death will come at any time," I do those things and I find them intensely beneficial. And at the same time, there's a way in which nothing ever really helps you come to terms with it.

So I guess what I'm saying is, I don't mean to offer a pat answer of like, "Yes, you know, grief can go away. You'll feel equanimity at all times with all things." That's never the case. But there's something about understanding that this is the essence of humanity, to be in this space, and that all humans at all times always have been dancing in this state of joy and sorrow simultaneously that is incredibly uplifting. The fact of us all being in this mysterious state together I find immensely reassuring and comforting.

CH: Absolutely. Thank you for sharing that. I'm sorry for your loss, but so grateful for this book. I don't know, I guess that's just my theme today.

SC: Thank you.

CH: So, I would like to ask you a question about narrating your own work.

Okay. So, we're Audible. We know that narrating is hard work, but is it also energizing. How do you find narrating words that you've written?

SC: I actually loved doing it. The person who narrated Quiet was amazing and I love her as a person and I love her as a narrator, so no disrespect in that way, quite the opposite. Now that I've done it, though, I can't imagine not narrating one's own book because as the writer, you know exactly which part of the sentence you meant to emphasize and you know exactly what you wanted to convey with each word and with each idea. And I really am a writer who every single word is deliberate for me.

CH: I get that impression.

SC: Yeah, totally. So, as I was narrating the audio, I was like, "Oh my gosh, the freedom to be able to choose the right emphasis is incredible."

And also, I will just say I love Audible and I love the experience of listening to audiobooks. There's something about having a writer's voice in your ear that is so primal in such a comforting way. I think it taps into thousands of years of oral storytelling, and that feeling of being told a story by a parent or grandparent before you at bedtime when you're little, it taps into all the best things. So, I loved it.

CH: Absolutely. Would you care to share anything that you love listening to or that you're listening to now?

SC: I mean, I loved listening to the Harry Potter books with my kids. That was a really big one. Oh, there was this audiobook that was read by Erika Schickel, The Big Hurt. Oh my god, I love that. Did you listen to that one?

CH: It was amazing. Yes.

SC: It was so, so good and I just walked around with her voice in my ears for however long it took me to listen to that book. It was so good. And then conversely, I won't say who, but I heard another author in a podcast not long ago, and he had the most amazing voice, and I had never read his books, so I went straight to Audible looking up his books, and none of them were read by him. And it made me feel like, "I'm not sure that I'm going to listen, because I wanted to hear his voice."

"For all of us there's going to be joy and there's going to be these painful moments. And the question is, what do you do with that pain when it comes to you?"

CH: Well, someday you'll tell me who that is. But, I have to say, any listeners, after you finish Bittersweet, I think it's time to go look up Erica Schickel. And if you are an author listening to this, please know, we love to hear you read your work.

SC: And it's worth it. It is a lot of work. It took a full week. We probably did like five hours a day, I think, for five days. But, you know, totally worth it.

CH: I just love hearing your ebullience about reading, because we do know it's work, and we hear the work part a lot. And to hear that it's worth it and that it made you feel good to do really makes my day.

If you feel like sharing, do you know what you're working on next?

SC: I do have another book idea, but I invest so much time and energy into each of my books that it will be a while before that one comes out.

CH: Okay. Well, I'm glad that you have a lot of ideas in the pipeline. Speaking for myself, personally, I'm here for it and I bet your other fans are too.

So, I have one final question, which is, is there anything else you would like to share about Bittersweet with listeners? Is there any question you wish you got asked that you could answer in your own way when you go on tour?

SC: I guess I would like to talk about just one big lesson that I feel like I've learned from immersing into the bittersweet tradition all these years, which is that for all of us there's going to be joy and there's going to be these painful moments. And the question is, what do you do with that pain when it comes to you? There's essentially a fork in the road that we all face, which is, you could not acknowledge it and repress it and invariably take it out on somebody else, or maybe take it out on yourself. Or you could do what the bittersweet tradition advises, which is to transform the pain in some way into beauty.

Maybe that's through a creative act and maybe it's through a healing act, either of yourself or of other people. I give a lot of examples of people like that in the book. One of my favorite ones is Maya Angelou, who had had just an incredibly harrowing childhood, to the point where she stopped speaking for five years to anyone but her brother. Literally, did not speak.

She was so afraid of what her voice could do until a woman named Bertha Flowers took the young Maya under her wing. This is all told in her book I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. She describes Bertha Flowers as somebody who often smiled but rarely laughed, which I thought was such a masterful way of describing, just in a single stroke, whatever shadows had been in the life of this woman who takes the young Maya under her wing and first reads to her from Charles Dickens, from A Tale of Two Cities, and the young Maya says, "I had never realized that words could sing before, but the way that she read them out loud to me, they were music." And then she has the young Maya start reading out loud herself. And before long, the young Maya is writing herself and she's writing poetry, ultimately, and plays and memoirs.

And then there's a foreword that was written years later to I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. The person who wrote the foreword talks about how she herself had been a young Black girl growing up in the South and had had experiences uncannily similar to the ones that Angelou describes in the book. She just couldn't believe that her own struggles were experienced by someone else who had now transformed those into something beautiful. And the woman who wrote that foreword was Oprah.

And I just thought it's such an incredible thing. The idea that one person can take the time to transform what's happened to them and then it can impact another being who they've never met, who's growing up in a different generation. In this case, the two people got to meet, but it could be that it impacts somebody who lives 1,000 years later than you did. It's just incredible to me, the ways in which telling the truth of what it's like to be alive can be so incredibly connecting and healing.

And I don't mean to say, by the way, that we all have to write a great memoir that's going to survive for a century. That's not really the point, you know? We can express these things in everyday acts of beauty, or connection, or healing. In the smallest acts, these things can be expressed. The example of the Maya Angelous of this world are just the grand examples that makes it possible for us to do these things in small everyday acts.

CH: Well, on that note, I need to thank you, Susan. I need to thank you personally for your work, which has meant a lot to me. And I need to thank you on behalf of Audible and Audible listeners for your time today and your really thoughtful answers to my questions.

SC: Thank you so much, Christina, for having me and for being such an awesome interviewer. So amazing to connect.

CH: Thank you so much. And listeners, you can download Bittersweet by Susan Cain at Audible.com now.