Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

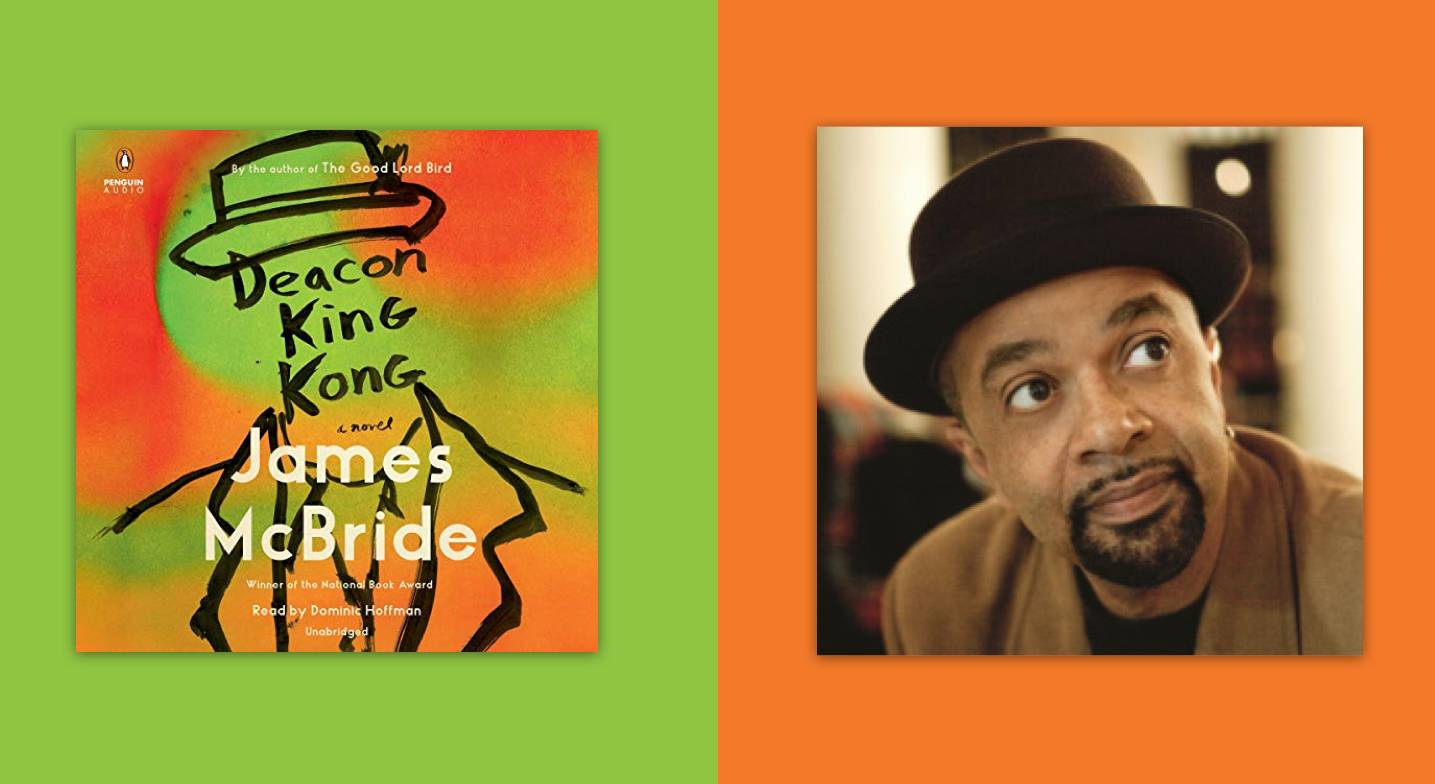

Abby West: Hi, I'm your Audible editor, Abby West, and I'm delighted to be here today with James McBride, former reporter and author of the National Book Award-winning The Good Lord Bird, his modern-day classic memoir The Color of Water, and many other works. But we're here today to talk about his new novel, Deacon King Kong. Welcome, James.

James McBride: Well, thank you. Delighted to be here.

AW: Deacon King Kong starts off with a very public shooting of a drug dealer by a seemingly harmless old drunk known as Sportcoat in a housing project in Brooklyn in 1969. It then follows how the shooting affects the witnesses, the victim, ancillary characters who are not actually ancillary, and even Sportcoat himself. I've seen it described as a crime novel, but it's also filled with vibrant characters in your hilarious prose. Do you consider it a crime novel?

JM: No. I never thought of it that way. But in fact, I think it's dangerous if you just classify your work as this or that. I mean, it's certainly set off with a crime, but no, I don't think of it as a crime novel. I don't think I'm good enough to write a crime novel. If I sat down to write a crime novel, I wouldn't be able to do it. I don't know enough about crime. I suppose I could do it, but what do you say? If you’ve seen Law & Order, what else is there to do? It's not a crime novel.

AW: How would you describe it without trying to pin it down to one thing?

JM: It's just a story of a community of people who know each other and who are all tied together by this wacky event that took place where the old deacon from the church, the old drunk, the neighborhood drunk, and who's this good-natured guy was walks around placid on time, gets soused and just pulls out his pea shooter and just fires it at the local drug dealer, and he causes a big ruckus. He doesn't kill him. He wounds the guy. It's an incident that sets off a lot of our story, but it's really about a community and how people learn to get along and how the community is about to change before drugs, I mean, before crack and all of that.

AW: Was the choice of the year very pivotal for you, with 1969 being such a loaded time?

JM: No, I think so, in part because it takes place in New York, and it was the year the Mets won the world series. It was the year that New York made a little bit of a comeback, and Brooklyn participated in that in the sense that Brooklyn in New York was heartbroken at the parts of the Brooklyn Dodgers even though that... even baseball fans were disheartened to see the Dodgers leave. Then the Mets with this hapless team, they won the World Series. It was a time of miracles. I don't want to say a time of innocence. That's overused.

AW: Deacon King Kong is set in a fictitious Brooklyn housing project called the Cause Houses. You grew up in the Red Hook projects in Brooklyn, and you still run a music program there, correct?

I think you have to accept people on their own terms, and as a writer, if you really want to humanize part of the world that most people don't know about, you have to first want to respect it and appreciate it.

JM: That's true, although I moved out of the projects when I was seven but used to go back in the summer because my godparents were there. I was very close to them, so I spent a lot of time in Red Hook as a kid, and then as an adult after I moved back to Brooklyn after I finished with. I just wish I had bought a property there. In the '80s, nobody wanted to be in Red Hook. I [remember] my Godfather's saying, "You could get that house there for $35,000," and I said, "Who wants to come here?" Of course, you know how that ended up.

AW: If only we knew.

JM: Red Hook is the hottest real estate in New York. But in any case, the housing projects that I knew as a child and as a young man are a little bit different from the housing projects in the book, but the story is the same. New York has 45 housing projects, and they all more or less look alike. They're these big red buildings where the poor are essentially housed and terrible things happen in the projects, but also, there's a lot of beautiful things that happen as well. It's a real village, and I really wanted to emphasize the beauty of the people that lived there, and their diversity as well.

AW: Yeah. I've seen you talk about the church and faith angle as well. Why was that an important part for you to play up?

JM: Well, I think the church is badly maligned in media, particularly the black church. But there's a lot of good stuff that still happens in church, despite some of the absolute morons who run some churches now. Some of them really have psychological problems.

That's the other thing about church. Church draws everybody. You get the best of the best. You get the worst. You get the worst hypocrites. Then you get truly religious people who are wonderful. Also, at least in the black church, you get women who are really sophisticated and really kind, and know a lot about a lot. The stereotype of the black church woman — a big fat mama with wig on and always saying, "You better go... Don't you go... " — you know that whole thing. I just can't stand that. It's just not true.

That's the problem. It's a stereotype. The women in my church, I mean, some of them are obese and some of them do talk like that a little bit, but they're very sophisticated. The elder ones I can talk about my problems with, they give me advice, and I have a lot more education and a lot more professional success than they do, but they know more about a lot than I do. I think you have to accept people on their own terms, and as a writer, if you really want to humanize part of the world that most people don't know about, you have to first want to respect it and appreciate it.

Of course, my book pokes fun at black women and pokes fun at everybody, but it does it in a respectful way that's funny, but you can be funny and respectful. It's just with the understanding that we are all equal. I think there's a difference between poking fun at someone and making fun of someone. I think when you depict certain characters — and this goes all the way back to Flip Wilson dressing up like a woman and al — the old black comedian Flip Wilson who would dress like a woman named Geraldine and was part of this television show and so forth. I never really found it that funny. I wanted to show how funny my community can be in a human way that didn't insult anyone. I mean, maybe it insulted them a little bit. Nothing wrong with that, but not all the way.

AW: There's that comedic fine line, right?

JM: Look, most of my books have always been pretty funny because you can't laugh at yourself and laugh at your characters. Why write the book in the first place? I mean, unless it's an academic book, there's no need to do it unless you can bring people some joy and some laughter and some relief from their own suffering.

[Narrator Dominic Hoffman] really knows how to inhabit characters. He understands my work.

AW: There you go. The Good Lord Bird imagined a relationship between abolitionists John Brown and — I've been changing up my language lately —an enslaved person who joined him in his mission. Kill 'Em and Leave is a deep dive into who is James Brown. How do you come to your stories, or how do they come to you?

JM: Well, the John Brown story was something where I really wanted to write about Abraham Lincoln, but after meeting Carl Sandburg, I just decided that I wasn't good enough to. Carl Sandburg had done it [with Abraham Lincoln]. And so many others behind him had done it so well. There was nothing else to really say that was new.

I stumbled on the John Brown story when I was in Eastern Maryland at a historical society, and I was going through a book they had that was a diary of a Jewish merchant on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Most of the entries were very brief, like “Mary Smith came in, and she got sick. And the next day John Smith came in, and he had his horse. He bought three pounds of flour.”

Then there was an entry where John Brown attacked Harper’s Ferry. It was a long three or four-page narrative about the attack on Harpers Ferry that John Brown participated in. I just became fascinated with it. I went to Harpers Ferry right away, and I became fascinated with the story. Then it was just about trying to figure out a way to tell this story that was this unique.

With James Brown, certain members of his family asked me to write his story, so I just did my best in that regard. And with Deacon King Kong, I felt that in my heart. It’s just a story that I felt in my heart because how many people, how many of us know somebody who gets drunk at 20 and dies at 80, you know what I mean? It's just a lovable old man who has a story and takes us into a neighborhood where there are Italians and Irish and cops. People just are forced to get along because there are no cell phones and it's New York and it's Brooklyn and nobody has money. You just do your best.

AW: I love that. You have had the really great fortune of having wonderful narrators for all of your work, honestly. J.D. Jackson narrated your memoir, The Color of Water. Michael Boatman did The Good Lord Bird. Leslie Uggams did Song Yet Sung. Dominic Hoffman did Kill 'Em and Leave and was part of the ensemble for Five-Carat Soul, your short story collection, and now he's back doing a pretty wonderful job on Deacon King Kong. Did you have any input in his return casting?

JM: Yes. I specifically asked for Dominic Hoffman. He's just talented. He really knows how to inhabit characters. He understands my work. He's obviously a very gifted actor in his own right. I'm lucky to have someone that good reading all 30,000 words of Deacon King Kong. I mean, that's a treat. There are some really, really good actors that read. I listen to audiobooks because I drive a lot, so I'm always listening to audiobooks. I'm listening right now to Devil in the Grove, narrated by Peter Francis, and it's very good. I'm always listening to books. I have a lot. I listened to quite a few. I listened to the guy, the rapper guy. Jeez. I should know his name. Oh, his name is Rakim.

AW: I think Rakim's book is called Sweat the Technique. Yeah, that's the name of that one.

JM: Very good book. I'm not a big rap guy, but I remember Rakim when he was at his height. I was not surprised to learn that he came from a family of musicians. His mother was a singer, a serious singer, and family of his brother was a jazz musician. I can tell by his music that he is a talented musician and a talented wordsmith as well.

AW: Nice.

JM: He's an important voice in the American musical tree, if you will. I remember Wyandanch when I was growing up in New York. We were scared to go out there. They said it was rough. I never went out there. I had a friend who had a family out there, and he said, "Wyandanch, you can get beat up out there," so I was always scared to go out there, but I'm not surprised that Long Island has produced someone like Rakim because it was quite dense, they had quite dense black communities out there with the usual talented people that come from any group.

[I listened to] a bunch of books, Stephen King's The Institute. There's some really good books, just really, really good. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich is probably my favorite audiobook, and I don't know who read it.

AW: That's a long one, isn't it too?

JM: William Shirer wrote it, and whoever read it was clearly one of the all-stars of reading. Look, the audiobook world has obviously grown quite a bit since it first got started, so obviously the actors are a lot better and, but whoever read The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich was just amazing.

AW: The narrator for The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich doing a Herculean job was Grover Gardner, who really did a great job with that.

JM: That's right, Grover Gardner. Yeah.

AW: It was 57 hours long.

JM: Yeah, well, that was 57 hours of two magnificents because that's one of the most important books, in my opinion, in the last 100 years. If you listen to Grover Gardner read Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, it will help you understand where we are now in America in terms of where America is now in here in the year 2020, early 2020, pre-election 2020.

But I think Dominic Hoffman is my favorite [narrator], and so I'm glad he agreed to read the Deacon King Kong because he really understands characters.

AW: Did you two ever consult while he's recording or before he records?

JM: No. I've never met him. I don't want to mess up his groove. Let him go. Look, every king or queen needs to have their own kingdom or queendom, if you will. An actor that talented, there's nothing that you need to tell them unless there's a specific sort of coloring or a specific scene that the whole thing pivots on this set scene but I think they can read it because the difference between a book and a movie or book and a play or a book and a screenplay is book, a novel anyway. Pretty much explains that world. The novelist is not in the room. He's not in the room directing the episode or he's not on the theater directing this stage play. He or she is just the puppet master. They're pulling the strings, and readers are expected to follow. I think the most actors who read books on tape know what the novelist is trying to do. Look, if he has to ask me what I'm trying to do, I haven't done my job.

AW: Fair.

JM: If he has to ask me what's my motivation, then I obviously haven't done the work.

AW: Nice. You pack a lot of fast-paced, rich, wonderful storytelling into your sentences. Does audio factor into your writing at all? Do you think about how your narrators will tackle some of the complexity of your sentences? How does that all work for you?

JM: No, I don't think about it at all. I leave that to the narrator to figure that out, but I am sure of one thing that when people talk, they don't talk in long sentences. Your best writers can write short and long sentences, but I always tell young writers that it's better to write short than long. Now, that said, someone like Jim Harrison, he can write a paragraph that lasts for pages and pages and hold it together, and so can Toni Morrison. I mean, the great ones can do it.

Harrison was a really underrated, just extremely gifted writer, author of Brown Dog and many other books, but I tend to try to keep my sentences short. I think that comes from my journalistic background, but I don't read the sentences aloud, and I don't do all that fancy stuff. I just get it over with. Sometimes, they go long. Sometimes, sentences will run long, and you find a paragraph stretching into the horizon, but generally I try to keep it down.

AW: I think whatever you're doing is working for you. An adaptation of The Good Lord Bird will soon premiere on Showtime, and you've written for Spike Lee movies, and particularly off of your work, like Miracle at St. Anna. Has it made you at all think more cinematically when you write novels?

JM: Not really. I don't really think about that. Well, first of all, I never see my stories in color when I'm writing. If they become movies or films, they end up in color, but I see everything in black and white. It's really hard for me to describe or even work color into my stories because then I have to really fictionalize not really seeing it. It's just the problem. It's just a workaround to me, but I don't think in terms of cinema or anything like that. I just I think in terms of character because if your characters don't work, it doesn't matter. They're not going to move from room to room no matter what.

AW: Good point.

JM: It’s just a different language, really.

AW: Was that hard for you to switch gears when you did start doing screenplays?

JM: No. Screenplays are a lot easier. I mean, the difference is that if you just imagine like when you get a key to go to a hotel, and then you come off the elevator, and you're just walking down a long hallway. With screenplays it’s like that hallway, and you have a key to this room, you can get in that room, peek in, but then you have to close the door and go down because you want to see the other room, you have to get the key and go look in there.

It's all spine and muscle, so using that sketch or paradigm in your head. The hallway would be the spine. The rooms would be the muscle. You pop into a room, and you explore that muscle, and you go right back to the hallway, which is the spine, and you just keep going down the hall. That's how it works. At the end, I suppose it's the last room you hit, there's some sort of resolution, and you're out.

A novel is different. With a novel, you get off the elevator, and there's nothing there. It's bare walls, and you begin to build. You build however you like to build. Sometimes it works out. Sometimes you build yourself a room, and you're trapped in it. Like painting yourself into a room, you can't get out, and then you just put that book together. That didn't work, then go to the next one.

AW: Why am I not surprised that you just described that so eloquently? Thank you. It might be what you do, right?

JM: Well, I can't remember what I do from one minute to the next, but I'm glad that works.

AW: I've seen you talk about how you accept failure as part of your creative life, but you never dwell on it. Can you share a little bit what you've learned over the years about that part of the process?

JM: Well, most of the writers I know when I started working in journalism stayed in journalism. I think there are a lot of reasons for it, but I think if you really want to write seriously, you just have to be willing to accept the fact that most of what you write won't really do that well. It won't be accepted. It won't be read. You just have to learn to just say, "Okay, well... " I mean, writers are insecure people, and they're often afraid to say, “I know it’s the truth is that I don't know what the hell I'm doing. I kind of do, but I really don't. I just go by faith and hope that this will work out, this particular story where... and I just push in.”

But I think it's better to just push in and push forward into unknown territory than to go back and keep sweeping the broom across the same old floor because you know how to clean that room. So you take an old broom, and you just sweep out on the corners, and then you got a nice little neat little room. How boring. I would just die just doing the same old thing again and again. It's better to fail and have fun than to just be doing the same thing successfully again and again and again. I mean, that's not interesting.

I should add that when I was a child I saw my mother [and] she often failed in a lot of stuff. She just would forget all about it. She just simply forget all about it and just go on. Sometimes people have problems with that for reasons I don't understand.

AW: Did you deliberately try to instill that in your own children? Did you think about that sort of ethos that you picked up?

JM: Well, I was just thinking about that because I'm divorced. My two oldest children, I really wasn't allowed to raise them. I shouldn't say I wasn't allowed. My ex-wife... She had more influence on them than I did, but my youngest boy, who I raised these last five years as a single parent, I've had a lot of influence on him. He's just a different person. Not that I'm a better parent my ex-wife. My ex-wife's a great mother. She's great person. Yeah. Okay. But I think a child should be allowed to fail, and there should be certain disciplines that are in place when you're dealing with kids. You don't ask them what they want when they're 9 years old, when they're 12 years old even, which I guess is what you do. This is what you do in this house, and if you don't like it, well, then when you're 18, you can always go to the other house. I won't hate you or be mad at you, nothing, but this is what we do here.

Then there's a certain amount of responsibility to take on, and you're just expected to do it, and because it was just me and my youngest boy, he became more responsible and became more mature. Also, when I had to do something, I just brought him along. When I started the church program in Brooklyn, he came, and he taught too. It helped him a lot, really. He's seen me fail, and I mean, he's watched me build my career back up after the debacle of my divorce.

I mean, I didn't tell him about it. In fact, I've never spoken to him about it at all, but he's seen. Children know, and they watch. Look, my mother never said, "I'm failing at something." I was just watching. She would just be humiliated by something, and she would simply forget it and go on to the next thing.

AW: There was that resilience.

JM: She wouldn't make a speech about it or something. She would just get to the next problem and solve that one.

AW: Well, I think that's a great lesson to teach to not just kids, but definitely to us writers as well to just keep pushing past any of that.

JM: Yeah, you have to keep trying. If you're a writer, you just keep trying. You just fail and fail better and fail better. The joy is in the journey, and if there's no journey, there's no story. Part of the joy of writing is it's just the joy of doing it. I mean, half the fun of eating M&M's is going to the store and knowing you're going to get them. I mean, I'm not making a cheap pitch for M&M's, but half the joy of getting candy or chocolate is the joy of riding to the store or walking to the store and getting it. That's part of the fun. If you're a writer, you want to get all that.

AW: Well, I can't think of a better, more optimistic and inspirational tone to end on. James McBride, thank you so much for talking with us about Deacon King Kong, which is available on Audible now.

JM: Well, thank you very much. I'm delighted to be talking on my favorite audiobook listening platform.

AW: Thank you.