Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

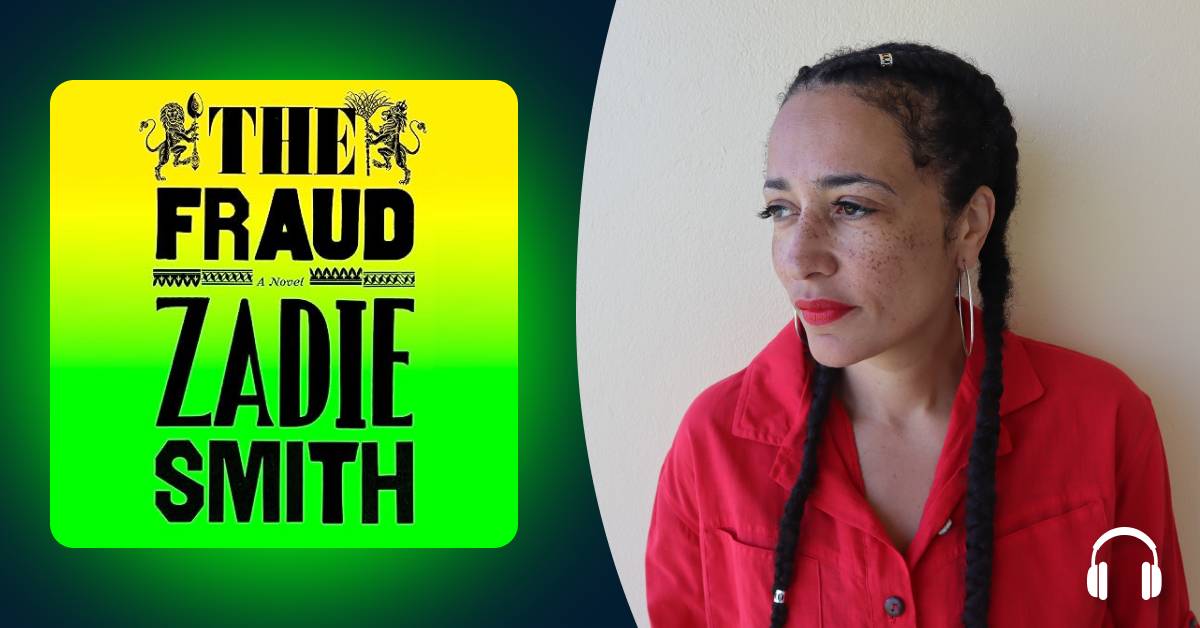

Kat Johnson: Hi listeners, I'm Kat Johnson, an editor here at Audible. I'm delighted to be speaking today with the one and only Zadie Smith, who is an iconic literary voice—and a personal hero of mine—with acclaimed works including White Teeth, On Beauty, and Swing Time.

Today she's here to talk about The Fraud, her sixth novel and first work of historical fiction. Set against a notorious case of alleged identity theft that captivated Victorian England, it has fascinating echoes in our world today. Welcome, Zadie. And thank you so much for taking the time to be here today.

Zadie Smith: Thank you for having me.

KJ: Thank you, it's our pleasure. One of the many things I appreciate about you as a writer is that your novels always take a little bit of a left turn from each other. They're their own individual worlds, and despite all the acclaim they've racked up, you always surprise us with something that feels like a leap in a different direction. So, I wanted to know if you could tell us about the leap that you took with The Fraud.

ZS: A few people have said that to me recently, and I was trying to think why that's unusual. I think maybe it's a ‘90s thing, that we really grew up with this idea that artists transformed each time they appeared. Like, I was a Prince fan, a Madonna fan, that was the whole deal. I think I've always thought about novels that way. It never occurred to me to write the same type of thing twice.

So in this case, there were various kinds of ideas going around about the past, particularly the British past, that I was hearing that seemed to be only partially the story. So, that was part of the desire and just the challenge of it. I knew I wanted to write it as a subscription novel and send it to friends in that way. And I had this idea of a kind of deconstructed Victorian novel, in these tiny little chunks. It was just a beautiful challenge. (laughs)

KJ: I love the tiny little chunks, because those short chapters always remind me of a thriller. But you're doing something very different here.

ZS: Right, yeah.

KJ: There's a lot to dive into in this novel, and we're going to talk about it, but I wanted to start with the title itself and this idea of fraud, because in the world right now, and especially in the publishing world where I'm sitting, there are so many books and interest right now in misinformation and disinformation, and the nature of truth. It feels like we're in this moment where it's so critical that we sort out what's true and what's false from all this information that's flying around us.

ZS: Right.

KJ: As someone who just wrote a novel about this, and someone who's such an astute observer, do you think we're in a new moment with this question, actually? And what did writing this novel teach you about the nature of truth and this question?

ZS: How do I answer this? I was interested, particularly in the contemporary moment, that some things are prosecuted very heavily. Like the idea, for instance, that writers are fraudulent or in some way inauthentic ... Over the past eight years, it seemed to me like not being able to see the wood for the trees. Like, a novel announces to you that it's not telling the truth. But the social platforms and the technology we spend our days in actively deceive you. (laughs) And presents itself as truth.

So, I was very interested in the kind of ire that's put on the realm of the fictional. Whereas fiction announces itself as fiction and when fiction enters the world as truth—like it does in the Tichborne case, or sometimes with people like Trump or O.J., or these, kind of, fictional figures who burst into our reality, that they have so much power. It's just so interesting to me that people are more willing to submit to fiction in real life than they are (laughs) to fiction in fiction. So, those ideas were in my head a little bit.

KJ: And the man who's at the center of this, the Tichborne case, known as The Claimant, he says he is a nobleman named Roger Tichborne, and his opponents say he's a working-class butcher named Arthur Orton.

ZS: Right.

KJ: And despite some major inconsistencies in his story, he enjoys broad populist support, which I really love in the novel how that is voiced by the character of Sarah. There are some very funny moments in the novel, where you're kind of revealing how characters use their biases to tell if someone is telling the truth. And that feels very relevant today. How would you characterize this sort of human tendency to judge others and tell if they're telling the truth, if you could?

ZS: I mean, since it's been published, lots of people have pointed out this Trump analogy, but to me it's quite different in that this is left-wing populism, which is very different from right-wing populism, but its mechanics are similar. But before I was thinking about any of those kind of mass political movements, the first thing that it brought to my [mind] when I began was O.J.—that sometimes when you're dealing with a corrupt system, a lie is what breaks it open.

That was such an interesting case to me, because obviously—and I'm sure some people think (laughs) O.J. is innocent, but I personally don't believe that—it was a lie encased in a larger corruption, which was that the American courts are racist. And also classist, so they give advantage to rich men. So, his case came through as ... obviously an obscene lie, but that gathered this support exactly because the people were aware that the system he was within was itself corrupt.

I think the Tichborne case is a lot like that. You know, of course, it's very, very unlikely that this working-class butcher was in fact a Catholic aristocrat. But these courts were sending working men to jail or to death sometimes for stealing a sheep, for stealing a bag of sugar. You could be 14 years old and steal bread and be sent to Australia and never see your family again. That had been going on a long time. And I think the working people of England were absolutely sick of it.

Even though this case seems absurd in the second trial—there were two, a civil and a criminal. In the criminal trial, under public pressure for the first time, the jury was made up of plumbers, taxi drivers, working men. Whereas normally to be on a jury, you had to be an upper middle-class aristocratic person, because they were the people supposedly who could judge you. So, it really did create change, even though it was absurd. That interests me, that sometimes the lie or the fictional—when it enters into a corrupt system—can almost disrupt it and overturn it.

KJ: That's so interesting. And I appreciate that you said this is … I've seen a lot of commentary that this parallels with Trump, but I'm a big true crime person and so, I thought a lot about how we're seeing so many stories now about scammers.

ZS: Right.

KJ: There's this huge appetite for scammer stories and at the same time, I'm interested in how it seems to coincide with, like, we're at this peak moment of imposter syndrome for a lot of people. And to me, it's like these things almost feel connected. Do you feel that way?

“Imposter syndrome … It's not a phrase that means very much to me, apart from in the sense that I've always felt like an imposter—to me, it's a very useful feeling. I'm much more worried about people who feel completely comfortable in their positions of power or influence. Those people frighten me. I prefer someone who has doubts about it.”

ZS: The scamming to me—and it was very popular in the Victorian period, too, and Martin Guerre and these famous cases of people who turned up and said they were who they weren't—it happens when the economy is broken and the middle classes have fallen out. That’s what happens. When there is no route to surviving decently, people start gaming it. And you see it again at the turn of the century, when you have these enormous extractive industries, the railroad, people making millions and millions, like they're making in the tech industry now. Then again you get these grifters in the 1910s and 1920s, trying to find a way through this system where people are starving on the street and people are making more money than has ever been made before.

I think that's where the scamming comes from. And all the contempt thrown at millennial scammers really annoys me, because I feel like you've given a generation with so little—no proper jobs, no proper housing, student debt that weighs on their back—of course they're going to find a way around it. So it doesn't surprise me at all that there's so many scammers in that crowd.

Imposter syndrome, I don't know. It's not a phrase that means very much to me, apart from in the sense that I've always felt like an imposter—to me, it's a very useful feeling. I'm much more worried about people who feel completely comfortable in their positions of power or influence. Those people frighten me. I prefer someone who has doubts about it.

KJ: I was wondering, in the novel there is this scene where Eliza Touchet is watching Roger Tichborne/Arthur Orton command this crowd, and she's thinking, "He accepted the public's adulation without a moment's anxiety, as if it were only to be expected. A pulse of doubt ran through her mind. Wouldn't a fraud be nervous? Wouldn't a fraud make more of an effort to convince?"

ZS: Well, she has another thought, which is, "Is this about men and women?" And that's certainly a thought I have had. When I first started doing this work, if I went to a conference or a university thing, and I had to give a lecture and a male writer had to give a lecture, I was constantly amazed by watching guys just go up to the podium—no notes (laughs) ... and just, like, talk. And that is inconceivable to me. To this day, if you ask me to your university to talk, I will have written a lecture-worth of words, with commas and semicolons. So I guess you can say, "Oh, well that's sad, unseen feminine labor" or whatever. That's one way to interpret it. But I also think I do a good job because I have some fear. (laughs) I really do the best that I can, all the time.

Of course, I can see a world in which she would wish that women did not have to feel that they had to do twice as well ... Also in Caribbean families like mine, you were often told, "You got to do it twice as well to get your head above the parapet." It's obviously annoying, and people’s self-worth should not be based on these meritocratic insanities. But for myself, I have to say, I'd rather always bring to mind the idea of effort and work than just think, "Well, here I am. (laughs) I'll just say whatever crosses my mind."

KJ: That's funny. I agree, I think that it can be self-perpetuating, right? Because if you over-prepare and then you do well, then you feel like, "Well, I better do that again next time." But I like your idea that this actually could be useful.

ZS: Yeah. The competency of women in these roles is so astounding, partly because they have to do this double row. But of course, you want a world in which they don't feel that way.

KJ: Right, right. So one of the pleasures, I think, of historical fiction is sorting out what's real and what's imagined. And one of the things I loved about The Fraud was how the novel itself kind of questioned these ideas, especially in regards to self. I'm curious if you could share any interesting tidbits on something you completely invented for The Fraud, or anything that was real that might surprise us?

ZS: It really is all real. The only big lie—which I wasn't intending to do, but because Mrs. Touchet became a main character, which wasn't meant to happen—is that Mrs. Touchet is not a part of this story, really. She died early, and she never would have gone to that trial. I don't know if Ainsworth went—I would love to know if he did. I'm very tempted to think he did, because a lot of his friends did. So, there's no reason to think he didn't. George Eliot did go. Dickens went. Like, people went, so I can entirely imagine him going—it's the kind of thing he would love. (laughs) But I have no proof of that. But basically, it's all true.

It's more that I had to remove things, like Wilkie Collins was around that table all the time. But, I had to make choices, you know. Wilkie Collins and Ainsworth and Dickens is a whole other novel. They had a big relationship—they put on plays, they were very involved in each other's lives. But a lot of it was just about containing the information. And just deciding what you wanted to focus on.

But it's all true. And it was so interesting putting it through a contemporary edit, because a lot of editors who read it couldn't believe parts of it. They, the American readers, couldn't believe that a Black man is in court giving evidence for three years in 1873. I'm like, I'm not trying to rewrite the canon ... This is not Bridgerton! This is actually what happened, that he was in court for three years. You realize there's a lot of history that people don't know. They don't know that racialized laws and Jim Crow laws did not exist in England in the same way—they just weren't there. So there's no block for a Black man giving evidence in a court, whereas in America I don't think you could do that until the late ‘50s, maybe—especially not against a white man. So this is a completely different system.

And then I think some of the language surprised them. Like, in the newspapers of the day he was referred to as "The Man of Color," Andrew Bogle. A lot of Americans were saying, "Well, that's just a phrase from 2016. Why is it in this?" (laughs) And I'm going, this is what I mean about you don't know the history. You think you know, but you really don't know. So, that was enjoyable, because I'd read a lot of it, and I'd learned a lot of it, but watching people's reactions basically saying, "This isn't the past that I know. This is the wrong past." But these are the facts.

KJ: Wow. And the character you're talking about, Bogle—this is another real-life person. He was a former valet of Tichborne's, and he became the primary supporter of the Claimant after Roger Tichborne's mother passes away. His story is so interesting, and I love how you bring in the history of, or the relationship between, England and Jamaica through Bogle. There's this great line in the novel, "England is an elaborate alibi." I was curious if you could expand a little on what you mean by that.

ZS: Well, that's the great difference between American and English plantation slavery, this offshore element—that it all happened outside of England itself. That we had incredibly abusive labor practices in England and indentured labor in England, but we didn't have slavery in England. So, that offshore element has allowed the British for a long time to dissociate from that history, pretty much. But I was just fascinated by the idea that with all these men and women of color running around England, in particular London, in the Victorian period, you would have known where they come from. They wouldn't have all come from those plantations—some of them would have come direct from Africa, some of them are business people, some of them are actually involved in trade themselves, but a lot of them would have been previously enslaved people.

And I guess, I feel the same way when I'm in London, you know, talking to recent immigrants, like parents in my kids' school or wherever. I read the news. I think, "Oh, God, we're just getting a coffee together, but I know where you've been. Like, you've been somewhere really extreme. You've done something really extreme. You've gone on a boat from Libya, or you're from Sudan, and you've just, like ..." These are the people I live amongst. And people don't often speak about their past. They're more interested in getting their kids to the school gates and getting their lives together. But looking at them, you think, "You've come from somewhere really extreme. Extreme things have happened to you, and here you are."

So, that's what I thought about Bogle, that he's in court, he's the very picture of self-possession. He's funny, he's smart, he tells great stories, but I know where he was and where he spent the first 24 years of his life. And that's just an extraordinary thought, that one life can contain those two facts.

KJ: Right. I keep kind of harping on this idea of whether self-doubt can actually be a marker of authenticity. I guess because this novel, you know, it does put us in Eliza's head a lot, and it puts us in Bogle's head a little bit. And they’re both plagued by this self-doubt. And Bogle, in particular—having had his identity really stolen from him—is wrestling with who he is. Does that make Bogle more believable in some ways?

ZS: When thinking about Bogle, I would use a kind of ready-made phrase. I don't normally like to use them, but I think survivor's guilt is the right phrase for Bogle. I think he has exactly the same traits as a Holocaust survivor. He can't believe he's not back there. He can't believe he has children and a family and somewhere to live. And he's mentally still there. I think that's absolutely fair. And you know, as writing those things, you're always kind of using not your biography but your emotions.

There were things I remember, like thinking of my father, who was in the second World War. He's one of that generation where you were aware that he had been places and seen things. I mean, he was at Belstone, and yet here he was in my family, seeming to be a normal person going about his day. But it couldn't have been the truth, right? So, I think I was always aware as a kid that these long histories have profound effects on people.

“There's all kinds of different frauds in the book, but the fraud of thinking you're talented when you're not is one of the most benign things that can happen to anybody. It’s not a crime not to have talent.”

KJ: And then do you think William is this other type of fraud? We're not so much in his head, but I guess I'm wondering, do you think William had his own self-doubt?

ZS: I mean, William's a good case of someone who should have had a lot more self-doubt. But he's a completely benign fraud. There's all kinds of different frauds in the book, but the fraud of thinking you're talented when you're not is one of the most benign things that can happen to anybody. Like, it's not a crime. (laughs) It's not a crime not to have talent.

And he also has many virtues. The virtues of kindness, of generosity, of being willing to accept the talents of others, which is very unusual in most people, talented or untalented. So, there's a lot to like about him. The fact that he's a bad writer is just one of those things. But he's an interesting guy in other ways.

KJ: So, switching gears a little more to the craft of the novel. I wanted to ask you about what it was like writing this historical novel. Did you do all of the research first? Or did you kind of do it as you were going? What was that like for you?

ZS: I did both. A lot beforehand, just to get the lay of the land and to have this kind of lightbulb moment ... All I remember about it was that I was at my desk—which is in my bedroom in my New York apartment—and going through the notes about Ainsworth and seeing this name Kenealy and thinking, "Wait, why do I know that name?" Thinking, "It can't be. It can't be. It can't be." And I Googled it and realized that this young lawyer was good friends with this young poet, who was a good friend of Ainsworth's 15 years later, who became a lawyer and was the lawyer on the Tichborne case.

When I had that realization I was like, "I'm definitely writing this novel." I know it's two novels, but I'm writing it because this is London. London was a place where all roads lead to Jamaica. People are intimately connected. Worlds collide. Literature and the lore, and that's how it was. And Dickens writes about it that way. It's true—it's a really intense metropolis in which you can bump into the same person twice in one day. (laugh) It's a crazy moment.

So, I'd done all the reading about both cases, but that was the moment where I thought, "Yeah, this is the thing." But then, I had advice from a good friend of mine, Daniel Kahneman, this German novelist, who was like, "You've got to get going. You've got to get started. You could read forever, so just get started. Read as you go along." And that was good advice. It was all pleasure. The hardest bit, maybe the sloggiest at the beginning where you're just reading one-volume histories of the Victorian period, just to get it into your mind, so that you know the basic shape of what happened from 1800 to 1900. Once I had that, I felt like, "Well, I got a basic sense." And you can start moving on from there. Yeah.

KJ: Right. And then, when it came to recording the audiobook …

ZS: Oh, I can't wait to talk about that, actually.

KJ: Yay! I'm so happy that you did it yourself. I know you've worked with professional narrators in the past for your novels. I know you have narrated your essay collection Intimations before, but this is a full-length novel. You have different accents. You have different characters. I cannot wait to hear how this went for you and how you made this decision to do this.

“My Scottish accent, as anyone Scottish listening to this will know, is not good by any measure. And I apologize to Scotland, and particularly the people of Edinburgh. It is not good, but it is passable.”

ZS: I never do them for just a purely practical reason, which is—even though the recording studio is maybe 100 yards from my door—it takes too much time. And my kids were small, and it was never a good time to say, "All right, I'm not going to pick you up for three weeks. I'm going to be in the studio." There was never a moment to do that. So I always said, "No, no, no, no, no." My brother did one for me at one point; actors that I liked. And I never listened to them, I have to say, because I have a sensitive ear and it's painful. I just didn't think to do it.

You just don't want to hear your own work, it's just not a thing that is enjoyable. So I never listened to them, and I kind of had a dissociated thing with them. And then, this time, I wanted to know, because it seemed to be really important that the actor was good. So they sent me these clips. And the problem was, they were all brilliant actors, but they could only ever do, like ... Some people could do the Black voices, some people could only do the white voices. Some people could only do the middle-class voices… I got really distressed. Like, I was listening to these things thinking, "I can't let this happen." So then I thought, "Well, if I do it, what's the problem?" And the problem is I cannot do a Scottish accent. Like, I can't.

KJ: (laughs)

ZS: I can do any other accent from around England. I can do American accents. But I cannot do a Scottish accent. So, I said to Penguin, "Look, this is the choice. Either you have someone who's going to do half of them bad, or you can have someone who's going to do most of them well and one of them really terribly." But I have a friend who's an actress, and she said to me, "Get a voice coach. Ask Penguin, will they get you a voice coach? Just four sessions." And Penguin agreed.

And so, we got this lady who was working on the Barbie movie at the time, so I got to learn a lot about the Barbie movie before anybody else, which was thrilling. (laughs) And she was brilliant, just brilliant. Helen Ashton is her name. She really helped me. And my Scottish accent, as anyone Scottish listening to this will know, is not good by any measure. And I apologize to Scotland (laughs) and particularly the people of Edinburgh. It is not good, but it is passable. It just functions enough that we can get through the book, and that's all I needed, because previously I couldn't even make the noises. It’s been like that since childhood, and it's always annoyed me. Why can I do all these regional accents, but what is it about Scottish?

And it's to do with the shape of the mouth. The vowels are very counterintuitive. So, I watched a lot of Maggie Smith in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. I worked with Helen. And just got something that will work okay. It's incredibly wobbly. And when I was in Edinburgh recently, I didn't do it. I got a stage member to read her part, because I was unwilling to humiliate myself in front of the Scottish. And also I know—bad accents drive me up the wall. Like, English actors who think they can do American accents and they can't, and vice versa. And I admire the people who can do it. The high point to me is Renée Zellweger doing Bridget Jones is one of the most perfect—not just a good English accent, but it's to the zone. It's like a North London publisher accent. She has an ear. She must have a genius ear. So, it pained me to do it, but I thought, "It will be less painful if I do it." That was the bottom line. It was less painful.

KJ: (laughs)

ZS: So, I'm sorry Scotland, but it could have been a lot worse, is what I'm telling you.

KJ: Right. Well, but it sounds like you gave it your best shot.

ZS: I gave it my best shot; I really tried. And then, the only other problem is Kenealy's from Cork, and oh my God. I have a house in Cork, me and my husband go to Cork all the time. That accent is, particular, let's put it that way. (laughs) Even the Irish find that accent extremely particular. So there's about eight lines in the book where I also murder the Cork accent, and I apologize to the people of Cork, too. (laughs)

KJ: (laughs) Well, all credit to Helen Ashton.

ZS: She's amazing. No, I think most Americans won't notice, but believe me—when that audiobook gets to Scotland, you're going to hear about it.

KJ: Well, my favorite is probably Sarah, because that character's so funny. And to hear that accent makes it even more enjoyable. Did you have a favorite character?

ZS: Oh, I loved doing Sarah, for sure. And, you know, when I was a kid I wanted to be an actor. My brother's an actor. It was a great pleasure to do it. And of course, I was aware that Dickens did it. He went all across America doing these crazy, almost staged versions of A Christmas Carol. He would shorten it. He did all the voices; he did all the actions. He was the ham beyond hams. So it was really fun to do.

I loved doing Andrew Bogle, with the kind of Jamaican accent of my relatives. I loved it all, actually. It was just so much fun. Actually reading it aloud instead of feeling—I don't know, nausea, or, "I didn't do that the way I wanted to," all the things I thought I would feel—I felt real pride and pleasure, and really thought, "This is the book I wanted to write. I wrote it the way I wanted to write it, and I'm glad it's in the form it's in."

KJ: Oh, that's so great to hear. And that's such a treat. I love to be able to hear the author, when that's a possibility. And this is quite a feat, because it's skipping around in time and, like I said, so many characters. I thought you did an incredible job. Thank you for that.

ZS: Thank you.

KJ: Are you a listener of audiobooks yourself?

ZS: I have a problem with ... Language is so much to me that it's not like I can listen to an audiobook and walk down the street—which is super annoying, because I can see it would be so useful to be able to do that. And I don't drive—though, I'm desperately trying to learn. But I've failed my test, so, I'm trying. (laughs)

KJ: Oh, no.

ZS: I love to listen to podcasts all the time and that kind of thing. But literary language is something that I personally—I'm too close to it. I need to see it. So I've tried to do things like listen to Proust... maybe that's not the best choice. (laughs) You get distracted, and you don't know where you are. I think the ones that would work for me are the propulsive ones. Something like Ferrante, for me, which I find propulsive. Or a thriller. It would have to be that kind of thing. I can't, when it comes to mood pieces or literature—I need to see it, you know, with my eyes.

I'm so struck, when I'm going on these book tours, how much audiobooks mean to people. Particularly maybe to women who have other things going on, whose hands aren't always free. It's really a big deal to be able to take in fiction in this way. It was nice to think that for once it's going to be my voice in their ear.

KJ: Yeah. I think for me—just if you want a little tip—sometimes it's nice to listen to something that you already know so you won't get lost.

ZS: That's it! And I think the biggest problem we have is on a long car trip and my husband put on Boy by Roald Dahl, which is, for all of us, family. And that was fantastic, because it's first person; it's direct. I know those stories very well from childhood. And my children were rapt. I was like, "Oh, my God, this is amazing." But it's quite hard to find things that would have created that. There's something so direct about the way he speaks to children, and ... just his voice. So we were all, yeah, completely rapt by that. It was brilliant.

KJ: He was an incredible storyteller. Can you share any books that you loved reading recently? Any recommendations for our listeners?

ZS: I really loved Stay True by Hua Hsu, the memoir which won the Pulitzer, which was absolutely brilliant. And I just read—it's out very soon, I think, in February—a book called Blessings by a Nigerian writer whose last name is Ibeh, I don't want to pronounce his first name because I think I will get it wrong. But it's a queer coming-of-age novel. He's very young, 21 maybe. It's set in Port Harcourt in Nigeria, which I found really beautiful. And I'm reading Fathers and Sons, Turgenev. Deep dive into the Russians. (laughs) That's pretty great as well, yeah.

KJ: Oh, good. Thank you for those, that's great. So now that you've gotten Dickens and this incredible story out of your system, or partly out of your system, can you share any details with us about what you're working on next?

ZS: There's a period between novels where you see a novel coming out and you really—it's self-doubt—you think, "Is this what I really want to do for the next, you know, who knows how many years?" So I have a novel in mind, but I don't know if I can talk about it. But it's a very different thing. It's just two people in it. And it's small. And I haven't decided yet, but it's around the edges of my mind. (laughs) We'll see.

KJ: Well, I can't wait to hear what it is and how it goes. And I also have to know, now that you mentioned your voice coach working on the Barbie movie... Have you seen the Barbie movie and what did you think?

ZS: Oh my God! You caught me on the rails. I really enjoyed it, and I hope that Greta takes her millions and makes more of her own movies, because she is a really great filmmaker. That's what I think.

KJ: She really is. Thank you so much for that.

ZS: Thank you.

KJ: Zadie Smith, it's been such a pleasure talking to you today, and, listeners, The Fraud is available on Audible now. Thank you, Zadie.

ZS: Thank you.