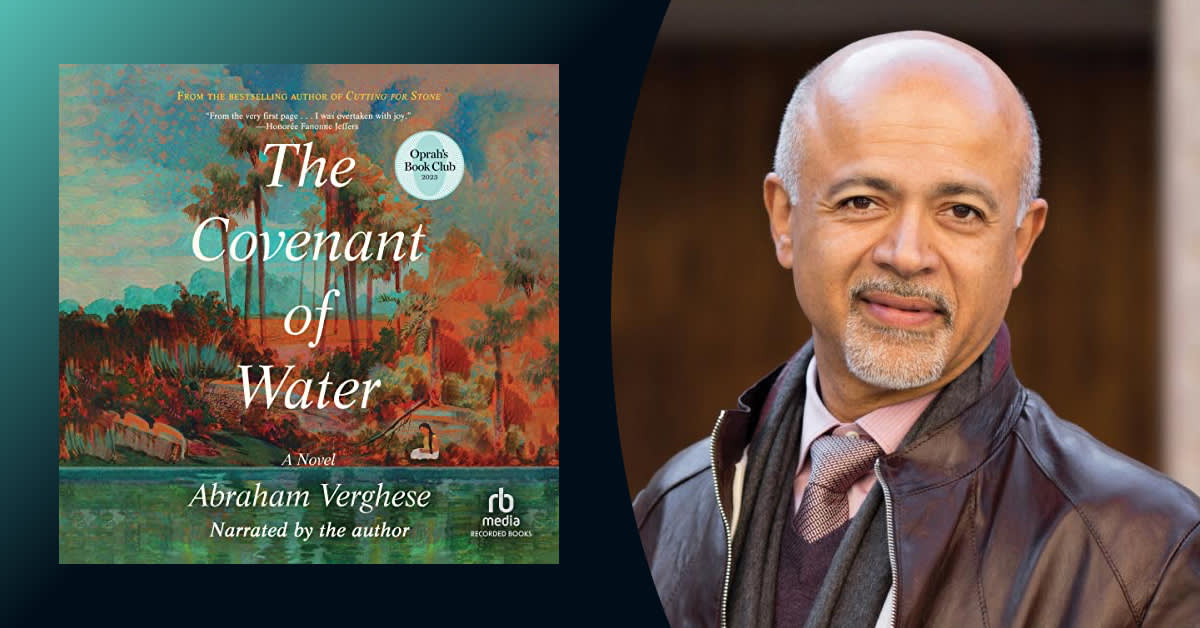

From the New York Times bestselling author of Cutting for Stone comes a stunning epic of love, faith, and medicine. Abraham Verghese's self-narrated latest, The Covenant of Water is set in Kerala, South India, following three generations of a family seeking the answers to a strange secret. I spoke with the author about his epic new release—which has already amassed praise from listeners and critics and a coveted spot on Oprah's Book Club—and all that inspired it, from bedside medical exams to a handwritten notebook filled with his mother's recollections.

Audible: Cutting for Stone was a phenomenon—and a true listener favorite here at Audible. It’s been quite a while since we’ve “heard” from you, book-wise. Was this intentional? Is The Covenant of Water something you’ve been working on for years, or did you step away from writing fiction for a while?

Abraham Verghese: The long interval wasn’t intentional, but I wasn’t in a hurry. It took a while to gather my thoughts after the success of Cutting for Stone and to think of a new novel. I don’t feel pressure to churn out another book, and it is because I love my day job. That is the advice I give budding writers—and I’m not being facetious. Get a good day job you love, because it puts huge pressure on your writing if you do it for a living.

I knew Covenant was going to be an epic multigenerational story; I anticipated it would take time. For better or worse, my method seems to be to discover character and story elements by writing. I don’t have the ability to plan out the whole story before I embark. I’m envious of those who can.

What made you choose Kerala, India as the setting of this story?

My family is from Kerala, though I was born and grew up in Ethiopia. The majority of the Indian teachers in Ethiopia, like my parents, who were hired by the Emperor Haile Selassie in the 1940s, were from our small St. Thomas Christian community in Kerala. Our Christianity is said to have begun with the arrival of St. Thomas (or “Doubting Thomas”) on the shores of Kerala in 52 AD. It’s similar to the traditional Orthodox Christianity of Ethiopia. There were so many teachers from Kerala that we had our own priests who taught at the theological college. So, I was being brought up in the tradition, albeit it in Ethiopia. Also, we spent our summer vacations with my grandparents in Kerala.

When my mother was in her 70s and had retired to Florida after teaching junior high in New Jersey, my five-year-old niece asked her, “What was it like when you were a little girl, Ammachi?” My mother was very taken with that question. How could she convey what her life was like in India in the 1920s and 30s to a child born in America? She wound up filling a notebook with her handwritten reply. She even had illustrations, because Mom was a good artist. The document had anecdotes and legends about our family. My two brothers and I had copies of what she wrote. I happened to pick her manuscript up again some years after I wrote Cutting for Stone. I was suddenly certain that Kerala was the place to set my novel. My only hesitation was that I wasn’t born in Kerala, and I am not as conversant with every nuance of life there as a native might be. But I had lots of great help from relatives and did extensive research.

What about writing makes you a better doctor? And what about being a doctor makes you a better writer?

I don’t want to make too much of doctoring giving a writer some sort of secret advantage. However, the fundamental skills of observation and of gathering disparate clues and trying to make a cogent whole—the clinical method—is useful to a writer. I’m an internist by training— my particular passion in academic medicine is the bedside examination, the time-honored skill of reading the body for clues. It’s an art that’s rapidly fading with our increasing dependence on technology. I’m always observing people for what the body is telling me about them—“reading the body”—and observing nuances of behavior and habit.

In short, I write in order to understand what I’m thinking. With a novel it’s more complex—you are telling a story, but also processing your own life. It can be a form of atonement and healing.

That discipline I suppose is helpful to a writer. Also, years of medical school, residency, and fellowship give you practice in applying yourself to one task for a long time. Conversely, writing helps me process my medical experience, particularly the emotions that are stirred in me by what I see. I became a writer because I felt the story and the tragedy of HIV in a small community where I lived in Johnson City, Tennessee, needed to be told. I described it in a scientific paper but that narrative in the cold language of science felt lacking. My attempt to make up that deficit became my first book, My Own Country. Subsequently, I watched my best friend and a former tennis professional descend into drug addiction—the desire to process that experience became The Tennis Partner. In short, I write in order to understand what I’m thinking. With a novel, it’s more complex—you are telling a story, but also processing your own life. It can be a form of atonement and healing.

You wrote Cutting for Stone after working closely with AIDS patients during the early, terrifying years of the epidemic here in the US—and then came Covid-19 and your next novel. I know this is not a “pandemic novel,” but did writing during this time stir up memories of the past or impact your writing?

The current pandemic certainly did stir up strong memories of the HIV pandemic. As a senior member of the faculty with administrative responsibility, I was involved with our institutional response to Covid. I wasn’t on the front lines as much as my colleagues in emergency medicine and critical care medicine or my residents. I did my share of being attending physician on the wards, and I saw many patients with Covid-19. During that time, I was trying to finish The Covenant of Water. It was a poignant juxtaposition because my fictional characters were threatened by mortal illness in the 1900s, while in real life, I was witnessing the same phenomenon in 2021 and 2022. Patients and their families in any era when critically ill turn to the same things—hope, faith, family, and ritual. Those human attributes are more or less unchanged since antiquity. That was instructive and deeply moving.

You narrate The Covenant of Water yourself—and it’s not a short book. What was that experience like? What made you decide to do it?

The book is challenging because it has many ethnic names and phrases, and although they are translated in the book, it would be jarring for readers familiar with Kerala or Madras to hear some words mispronounced or pronounced poorly. Even for me, Malayalam is not my first language. I’m sure people from Kerala will find much to criticize (and the fact is our people love to criticize!).

I wanted to narrate my book only if the director thought I was as good as a professional narrator, but with the advantage of being more familiar with the territory. I was happy to get the part.

Nevertheless, I thought I’d audition. I wanted to narrate my book only if the director thought I was as good as a professional narrator, but with the advantage of being more familiar with the territory. I was happy to get the part. I was instructed by a wonderful director, Peter Straub, and encouraged by the studio sound engineer, Jermaine Hamilton. I had to learn how to perform the book, and to learn how, by subtle alterations of pitch, to clue the listener in to different voices. There were many accents—Madrasi, Malayali, English, Scottish, Texan—but one had to be careful not to overdo it. I had to convey the passion that the words on the page evoked. There were many times when I was tearing up, as were Peter and Jermaine. In the process of reading, I also began to notice startling connections within the novel that I had not consciously put in. It was a reminder that so much of the novel is from the deep subconscious, or the muse, or the right brain—whatever you like to call it. It’s magical, but it doesn’t happen without hours in front of the manuscript and lots of blood, sweat, and tears.