Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

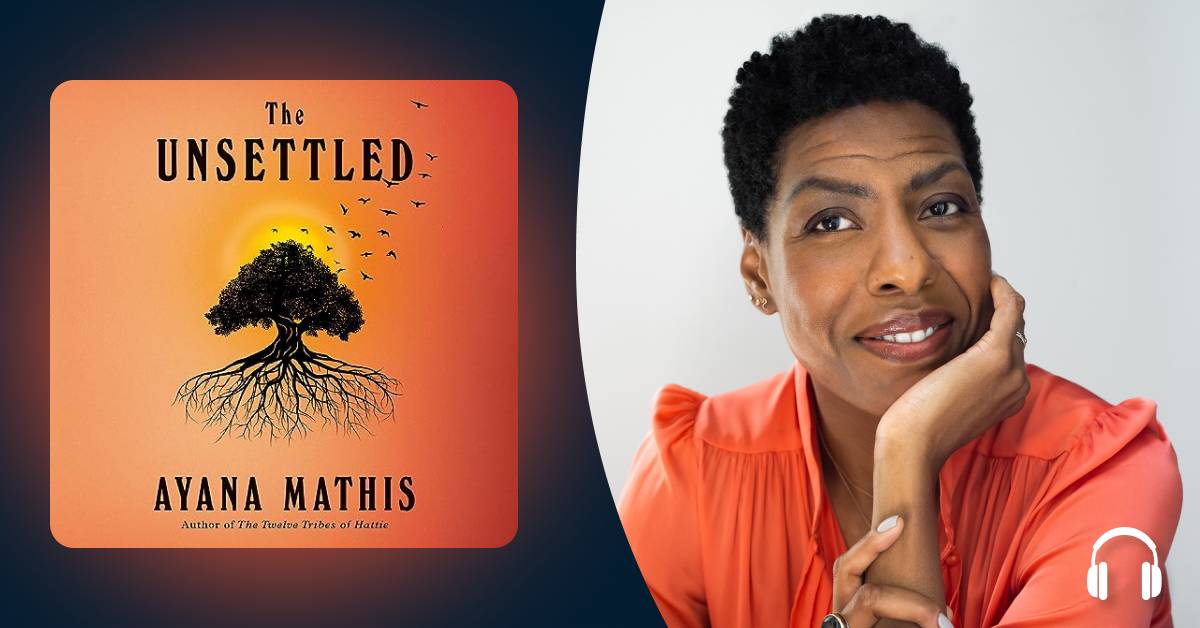

Jerry Portwood: Hi, listeners. I'm Jerry Portwood, an editor at Audible, and with me today is author Ayana Mathis. In her debut, The 12 Tribes of Hattie, Ayana Mathis presented a multigenerational story about the Black experience set against the backdrop of the Great Migration. Her prose inspired comparisons to Toni Morrison and other great storytellers. Now, in her second novel, The Unsettled, she presents another visceral, heartbreaking tale of longing and journeys, parents and children, dreams and disappointments. I'm thrilled to speak to you, Ayana. Thanks so much for joining us.

Ayana Mathis: Thank you so much, Jerry. I'm so glad to be here. This is very exciting.

JP: To get started, I do want to start with your first book, The 12 Tribes of Hattie. You wrote about Philadelphia and the dream of a new life and future for a Black woman and her children and grandchildren outside of the Jim Crow South, and I recall Hattie saying, "I'll never go back."

And now in The Unsettled, you have a young woman living in Philly who's trying to pick up the pieces of her life and return with her young son to her mother in Alabama. I just was curious—Did you realize that theme of Black women and human geographies would be so omnipresent in your follow-up?

AM: I did not. I know we'll get into this, but there're two poles in the book. One is Philadelphia, as you've said, and then the other one is a very Southern place. This book took quite a number of years to write, and (laughs) it kept changing around me and shape-shifting and really, frankly, being very irritating and hard to deal with. It was belligerent and recalcitrant. (laughs) But we worked it out.

What I did know earlier on was more about the Philadelphia stuff. The voice of the character who lives in that Southern place, called Bonaparte, that voice came early on, but I didn't know what to do with it, and I didn't know necessarily where it fit or even where she was, exactly. So, my kind of larger vision at the outset was more about Philadelphia than it was about the other place.

JP: So I know you live in Upper Manhattan, and you probably know Harlem pretty well, and there's been a lot of talk about this sort of reverse migration of people who are leaving the North and going back South. Some people are really excited about that and, in a way, I wondered if you thought of this story as a response to that sort of narrative of people returning?

AM: I think, in a sense. You mentioned how Hattie, in the first novel, how Hattie said, "I'll never go back." But, it was interesting to me, because then also in that first novel, Hattie really had a very contentious relationship with the South, but her husband, August, for example, was deeply nostalgic for the South. And then, their children were all sort of somewhere on a spectrum in between, disliking it and fearing it and kind of longing for it. And more than anything, just sort of having a big gap in their knowledge about it, so what they knew about it was kind of imparted to them but in a very piecemeal way from these parents of theirs who had very strong feelings about it.

So, in a certain sense, I think I've always been interested in pushing a little bit against these narratives of the North as a paradise and the South as a place from which to escape. I think that that's still happening in this new book, The Unsettled.

JP: That's what I was curious about—Bonaparte is fictional, but I wondered if it was inspired by any place. I mean, I do know of towns that were created and in ways, it was giving me these Zora Neale Hurston vibes of these sort of Black utopia or a Black city. Could you tell me a little bit about the inspiration for Bonaparte?

AM: Absolutely. I'm glad you picked up on that. I wondered if people would. Yes, absolutely. There're sort of three poles of inspiration—maybe we could put it that way—or three sources of inspiration.

One is certainly places like Eatonville in Zora Neale Hurston's Their Eyes Were Watching God or The Bottom [in Sula], which is not entirely a Black town but a Black section of a mixed-race town. So kind of drawing from the African American canon in that way and thinking about place and very Black places, utopic places, people's attempts to kind of make a free place despite the odds against them, was very much a part of my thinking.

There is a town in Alabama set on a bend in the river, which is called Gee's Bend. If people know Gee's Bend, they might know it for its quilts. There are some very famous quilts and quilt makers that come from there. One of the quilts—might be more than one, actually—is in the Smithsonian.

Bonaparte is not Gee's Bend, but it certainly was inspired by its geography and some aspects of its history that I imagine we'll get into later on, but Gee's Bend was a place in which people had been farming and taking care of their land. Black people had been farming and taking care of their land for quite a long time, and then, as a part of the WPA in the 1930s, there was this big effort to combat rural poverty.

Because, coming out of the Depression, we had been concentrating on cities, and there was this big push, like, "What do we do about rural poverty?" I mean ... given all the agricultural decimation and things like the boll weevil and cotton no longer being king, there was an enormous amount of rural poverty. And so, part of that initiative was to "give" (I'm doing this in air quotes) this land to maybe some groups of people who had already been living there and were already working that land.

And Gee's Bend was a place where that happened, and that is also what happens in Bonaparte in my book. So definitely a source of inspiration there, geographically as well. It's a very beautiful place on this bend in the river, and it smells incredible. It's a very beautiful place.

So there's that, and then I think the other part of it is—not necessarily staying solely with fictional recreations or explorations of Black utopias—there really just were a bunch of them that existed, that sprang up, in particular around the period of the Reconstruction, some of which may have stayed, many of which are, in fact, gone.

There're places like Mount Bayou, which is a settlement like this in Mississippi. There's an incredible place called the Kingdom of the Happy Land, which is in North Carolina. It's very mysterious; it sort of cropped up sometime during the 1870s-ish. There are not a lot of records, but something like between 50 and 200 people were living there. They were farming. They were engaged in all kinds of economic commerce. They were teamsters, which meant, at that point, you had a team of horses driving a wagon, and you were transporting stuff. That community eventually died out, but it was a cooperative model, so they were pooling resources, pooling land, pooling monies that they made, and putting those pooled resources back into the community and its development. So, those kinds of places which, again, did actually exist, really factored strongly into my thinking.

JP: It sounds like you did a lot of research and probably even visited places in Alabama for this.

AM: I did. You know, I have a weird thing about research, which is that I'm a massive procrastinator, and I'm also very easily tricked into thinking I have to actually write facts if I research too much, so I have to police my researching. (laughs) So, I visited Gee's Bend. I knew a little bit about these places that I've mentioned and then, certainly, of course, I've read Their Eyes are Watching God [and] all of those novels.

So, it was more like things that were floating in the ether of my mind that, as they kind of became manifest on the page, I just sort of wrote into them, and then did a little bit more research on the back end to kind of see how wrong I had gotten it. (laughs) You know? Or how right I had gotten it, or, you know, whatever. Yeah.

JP: Well, on the other hand, you grew up in Philadelphia in the '80s, and I assume you're about the same age as Toussaint, who's one of the younger characters. So, did you draw on your personal experiences for those parts of the narrative?

AM: Yeah, absolutely. In various ways, particularly in trying to recreate the kind of ethos and feel of the city at that period in the '80s. You know, it was a very particular period. Coming out of the '60s and the '70s, where there were all these freedom movements, all the Black liberation movements, the women's right movements, disability rights, the gay rights movement, all of these things are happening, and then you kind of get this hard stop in 1980. (laughs)

Ronald Reagan gets elected, and things just change enormously. There's a great deal of fallout from that change. I remember the ways in which certain aspects of my life changed enormously. And, of course, I was a child, so I wasn't like, "Ha, this is a political issue." (laughs) But I could feel that the zeitgeist had changed, and even little things—like the Head Start preschool program where I went to preschool and started when I was two—it still existed and still does exist, but everything just really shifted. So, the book is set in the middle of that and is trying to capture that strange, really kind of seismic shift—and how much it left people in various ways sort of marooned.

JP: We touched on this a little bit, but the narrative is told from the perspective of several points of view but primarily focused on Ava; her mother, Dutchess; and Ava's son, Toussaint. It's complex. You said you struggled with it in parts. It has jumps of POV, and I guess I'm just fascinated to learn how you outlined or mapped it out so skillfully. Can you reveal any of that process and any of the struggles?

AM: Sure. As I said at the outset, we were really in a kind of a knock-down, drag-out battle for years. (laughs) I'd figured out where Dutchess was and sort of where she belonged and kind of what she was doing. The Philadelphia sections remained really, really difficult—in part because Ava's voice was very difficult for me to understand. How to relay her trajectory was really difficult for me to understand, so it was just a lot of trial and error. There were a lot of thrown away pages and a lot of frustration. As I got a little bit closer—and by closer, I still mean probably about three to three-and-a-half years out from when I finished—I did a thing that I didn't have to do with Hattie, partially because, structurally, it was a very different book.

I ended up being one of these people like in a weird movie where there are all these index cards with plot points and chapters on a wall that I would move around and thumbtack and take them down, because it's oddly a very plotty book, which was not my intention at the outset at all. But the moving pieces were such that it became clear to me that it required a lot of really intricate, hair-trigger calibrations.

And, I couldn't hold it all in my mind, so I started this whole kind of whacky index card business, which actually was enormously helpful. I don't think I could have finished without having done that, actually.

JP: I'm really curious about how you inhabited the perspective of Toussaint, who is like 12, 13. You really have these moments that would frighten an adult, like when he's hanging out with the homeless and people who are addicted to drugs. We even see Ava's perspective, where she's like, "Oh, my God, what's my son doing?" I was just curious—How did you put yourself into those situations and be able to have that sort of innocence and that childlike wonder?

"I was really interested in pushing against some calcified notions of what certain people might be like. ... I really wanted to expand the notion of who is a safe person, who is someone who is reliable, who is someone who is respectable."

AM: I think childlike wonder is actually a really good way of thinking about him. I think that he finds himself in this situation where he's living in this homeless shelter, and his mother is continually receding from him, right? Like, she's receding into her memories; she's receding into depression; she's receding into all sorts of things. It had been for a great deal of his life just the two of them, you know? I mean, she has this kind of unsuccessful marriage, but that was a brief period, all told, in his life. So she was his anchor, and then she's kind of gone.

I think that what happens with him is that once his mother is gone from him, it really sets into motion a kind of process of questioning everything that he's been told is an authority—adults in general, school in general, the other sort of pillars that he would have, a place to live. All of these things are gone from him, and so he distrusts what he's been told or supposed to be the things that make sense and the anchors and the things that are supposed to keep him guided and safe. And he begins to look for other sources of companionship or understanding, and he begins to understand himself as an outsider—though he would not necessarily say that.

So, he stops going to school, and he's kind of wandering around, and in this wandering, he finds a tribe of people who are also outsiders. Though he certainly is, I think, initially kind of scared of them—some of them are kind of scary—but what he discovers is that quality or that understanding of oneself as being outside of the mainstream is something that makes him feel seen and safer and all of those kinds of things, and so he gravitates ever more toward those kind of people.

I was really interested in pushing against some calcified notions of what certain people might be like. You know? One of his sort of dear friends—who becomes a little bit of a surrogate father figure—is this homeless man who is struggling with a drug addiction. But that man is kind to him, and he's funny, and he offers guidance. I really wanted to expand the notion of who is a safe person, who is someone who is reliable, who is someone who is respectable. That character's name is Zeke, who may not be respectable by many measures, but he certainly is in other measures. So, I was interested in exploring that.

JP: Yeah, and other than Zeke, obviously, Cass, his dad, comes back into his life, and we get this moment where Ava and Toussaint are going to leave. They're going to go back to this bucolic land in Alabama, but then Ava gets wrapped up in Cass's dream of communal living and undoing social injustice—or righting the wrongs. I was just curious—I don't want to give too much away for people who haven't listened—but that ultimately fails, right?

AY: Yeah. Yeah. Spectacularly. Spectacular failure. (laughs)

JP: Cass seems to want to do good, but he makes some really cruel choices. Do you think those radical attempts at organizing were worth the pain it caused?

AM: That's a really interesting question. Do I think it was worth it? I never thought of it in that way. Hmm. I think that it was, actually. I actually do. I think that it was. Thank you for asking that. I think that it was.

I think it cost an awfully lot. I think it cost almost too much, but I think the thing about Cass—and I'll be careful here, because I also don't want to give away too much for folks who haven't read or listened—but the thing about him is that ... his motives and his methods are questionable at best. (laughs) At best.

He's not a great guy, but in some ways what underlies the reasons he wants to do these things [is} he's right about a lot of them. You know, he's right about Black people being in danger. He's right about the need to find some kind of safety. He's right about people's needs to pass some sort of legacy on to their children. He's right about all of those things.

It's as though the vessel was so flawed that, in the end, the vessel cracked, but what the vessel was holding—which is some notion of freedom and communal living and some alternative way of being—I don't think that that was so wrong at all. I hope I'm not getting ahead of us, but what happens in Philadelphia is kind of a dark mirror of what happened in Bonaparte in a way. Right?

That attempt at communal living lasted a lot longer, was a lot more successful, was a lot more loving, I think, and stronger, than Cass's attempt at the same sort of thing. Nonetheless, there is something in the attempt that is incredibly worthy and was really valuable. You know? I mean, Ava is a woman who, having grown up in Bonaparte, in this community that is quite singular and also sort of larger than life and a little bit mythical in a way, she spends much of her adult life looking for something like that. You know?

And for a time, she's happy, and for a time, she feels that she's sort of realized something. And so do the others. And there is something, I think, very worthy in that, albeit, or despite—I guess I should say—how things end up.

JP: So, I want to switch gears only slightly and talk about the narrator of the audiobook, Bahni Turpin. Have you had a chance to listen to the book?

AM: I've listened to part of it—I'm meaning to listen to all of it, but it's a busy time, so I haven't. But what I've listened to thus far I really liked. She also narrated The Other Black Girl and some other things, so I had spent a lot of time listening to her before we made decisions, so I'm thrilled with it, actually. She feels like just the right reader.

JP: I'm always curious what authors think of their books when they're interpreted by narrators and you hear these voices. Was there any kind of reaction you had to hearing Dutchess or any of the other characters?

AM: Absolutely. I think it's a strange thing, because, obviously, no one is ever going to sound like these people sound in your head. Right? If a film or a play or something were made of it, none of the people would ever look like the way these people look in your head. So, it's always a little bit jarring. Fortunately, with Bahni Turpin, it was jarring in a good way. It's like, "Okay, well, no, I like this." But, you always have this moment where it's just these people— especially if you've taken a long time with a book—these people's voices in the way that they came to me have been living in my head for a decade, So it's always really strange to encounter them out there in the world. (laughs)

JP: That's always something that a writer has to deal with as well, right? Once you put it out there, how other people deal with it. I mean, even the attention you got for your first book must have been overwhelming because of the Oprah attention. But then also, everyone kind of interpreting the book in their own way. Did that also create part of the time it took for the second book, or no?

“It took a few years really just to kind of return to myself, to some sort of quiet place inside of myself, and to tune out other voices and stop hearing them as I was trying to generate material.”

AM: Yes. Yes. (laughs) Categorically, yes. Writing requires—as you know; you're a writer too—it requires a certain kind of privacy. And it requires a certain kind of discernment, right? You can never, of course, fully judge your own work, but you make a series of choices all the time, in every sentence, every minute. There was a period in which both the privacy and my ability to discern were really interrupted. Like, instead of hearing my own internal barometer, making an assessment about a sentence or whatever it was, it was like the New York Times was doing it. (laughs) Which, of course, is no way to write. I mean, you can't get very far that way.

So it took a few years, really, just to kind of return to myself, to some sort of quiet place inside of myself, and to tune out other voices and stop hearing them as I was trying to generate material.

JP: I graduated from high school in deep South Georgia, and I know how little is taught about African American history. And I found works by Alice Walker and Toni Morrison and Ralph Ellison, and I was learning through literature. Because you do deal with certain points of American history in your books, do you feel that added responsibility that there will be people learning, you know, "Oh, this is the way that people struggled," or "This is the way certain people had to overcome?”

AM: I hope that the books will function in that way somewhere down the line. Sort of at the height of the pandemic, and the height of that fellow that was president at the time, I felt really hopeless. Really, really hopeless. A lot of people, so many of us, did. And it was very difficult to write, because it felt sort of stupid. I was like, "What am I doing spending my time scribbling in some notebook?" You know? Like, at the very least, I should be an EMT. What is this? You know? This is useless.

For a while, I kind of stopped writing. I was working on this book, but I just couldn't continue. And then, I was reading … It was probably James Baldwin, because I feel like whenever I'm stuck in any point, James Baldwin comes and saves me or chastises me, or tells me to get over myself, or something. We have this ongoing conversation. (laughs) I forget what it was specifically, but whatever it was, it made me think, "Okay, here is this genius kind of crying out in the middle of a period of enormous upheaval in which many people ignored him or thought he was ridiculous, or whatever, and yet, here we are, 50 and 60 years later, looking to him for insight and knowledge and a path forward."

So it made me think, "Well, at the very least, maybe this work ... creates an archive." My time would really be better spent being an EMT, there's no denying that, but perhaps what I leave is a record, like the work that has been left to us is a record. And when it serves, or when it can be of use, we find it, and we pull it out, and we look at it, and we are buoyed by it and inspired by it and guided by it.

I don't aspire to guide in the way that, obviously, the greats that precede me do, but in any case, I do think that in really dark times—when perhaps it feels as though you're just kind of screaming into the wind—there will be some other time ... Things pass. That's the only thing that we know for sure, right? Things change.

And some change will come at some point, and we will need these records of now, of what people were thinking and what they were feeling and how they were reacting to things, and they'll be a help in some way. So that's kind of how I think of it, like we are all creating some sort of archive in a way.

JP: That's great. I connected to that. I was thinking about this idea of resilience that’s seeped into the vernacular and this concept that seems to be at the heart of what your characters endure after years of trauma and systemic racism. You offer this—and I don't think this is giving anything away, because it's in the prologue—but you offer this ray of hope with Toussaint.

AM: Mm-hmm.

JP: So, I'm just curious, what do you think about that idea? Is it a trope you're working against or that you're conflicted by?

AM: Conflicted. I think that resilience is a hard word, right? Because, it's become a cliché, and it's become a way—I think that's probably the exact reason you're asking me the question—there's the cliché aspect of it. Then there's this other kind of dehumanizing aspect, like there are certain people that can just be put through every sort of abomination, and yet they will come out of it, and they'll be fine. Or if they're not fine, they'll come out of it—and that's dehumanizing.

Then the other part of it, I think the other side of it, is that it also creates a lot of issues around accountability, because it's like, "Well, they'll survive it, so then how much are we responsible to make the things that they're surviving any different? Because they'll survive it.”

JP: if it doesn't kill you, it makes you stronger sort of thing.

"I think I'm always struggling with trying to figure out how to make human beings that can and do survive the worst stuff without having that worst stuff be totalizing in a way that they become inhuman vectors of suffering."

AM: Exactly. And so, there are a lot of problems with it. And then, at the same time—which I'm aware of and worried about (to use maybe too frank a term)—I don't want to create these characters that are just pain bodies. For whom there is no hope; there is no ray of light. They're just going to struggle along in enormous agony forever. I don't want to do that, either, because that's also dehumanizing. Right? You could find people in the worst sort of situation and someone will crack a joke, and someone will have a memory that is precious to them, or whatever it is. These are just human things.

So in a certain sense, I think I'm always struggling with trying to figure out how to make human beings that can and do survive the worst stuff without having that worst stuff be totalizing in a way that they become inhuman vectors of suffering. It's a really difficult struggle, and I would worry about it. I was like, "Wait are these people pain bodies? Or, are they people in pain?" And, hopefully, they're people in pain and not pain bodies. I don't know. Time will tell, I guess.

JP: I also want to ask you about the title. It seems like there's a lot of different meanings embedded in The Unsettled.

AM: I do think there's a lot in the book about notions of land and ownership, but that’s a whole other kind of can of worms. But what I will say is that I think there's an essential struggle around having a place or belonging to a place that can be home and can be safe and all of those things, but then, in this country, as in most of the West, there's an essential kind of tension there, which is that no matter where one might do that in the United States, it's not your land. I think that's something that Dutchess, she mentions it at various points. She'll say, "Well, it's not ours anyway.”

But it's complicated, right? Because, these are enslaved people who are brought to a piece of land, so they have to be home; they have to make some kind of home somewhere. They can't go back to where they were taken from, so then they settle on a place to which they were brought, with the essential complication because, of course, that place to which they were brought is not theirs. There were just a lot of questions there for which I have no answers. But I think it wanted to kind of poke the question a little bit, or just at least raise the complication of that.

JP: There are so many authors with books coming out, you included, and you're about to embark on your book tour. Are you excited? Are you nervous? Your friend Justin Torres has a big book coming out this fall as well. Do you guys talk? Do you celebrate? I'm just curious.

AM: I am excited. I'm also very anxious, because it's been so many years since Hattie. So, I kind of forgot what it was like, in a way. (laughs) You know? I forgot about review anxiety and all of it. I got my first one just yesterday, and I opened my email, and there it was. Literally, my heart was pounding—like a person in a movie or a bodice ripper. “Her heart was pounding.”

JP: So, are you an author who reads the reviews, or no?

AM: I do. Maybe when I am sort of, you know, venerable—in 30 years. You know, I've written eight books ... I should be so lucky, but let's just indulge my fantasy. Maybe at that point, I'll say, “Reviews schmaviews!” and I won't look at them at all. But I do— totally do. What I don't do is comments. As much as I am so glad that people read and engage, but that is overwhelming, because there's so many of them, and there's so many different takes, so I don't look at that stuff. But I can't help but look at the reviews. I wish that I were a writer who could say, "Oh, no, no. The work speaks for itself. It's out there, and that's that." But no, I'm not that evolved. So, yeah, I read them. (laughs)

JP: Before we wrap up, I was going to see if you had any favorites of the year so far.

AM: Well, I'm reading Justin's book now, and that's shaping up to be a favorite. I've just recently read Chain Gang All Stars, which I thought was really terrific. I'm trying to wrangle myself a galley, but nobody will give me one, but I'm very excited about Anne Enright's The Wren, The Wren. I really do just love me some Anne Enright. And I'm super excited about Jesmyn Ward's book.

JP: Well, it's been so great talking to you. I feel so inspired hearing how your creative process works, and I just want to thank you so much again for spending time with us, Ayana.

AM: Thank you so much for having me. It was a real pleasure. It's really great. I love when it's a writer that we get to have these conversations, so thank you.

JP: And, listeners, you can find The Unsettled on Audible now.