Note: Text has been lightly edited for clarity and does not match audio exactly.

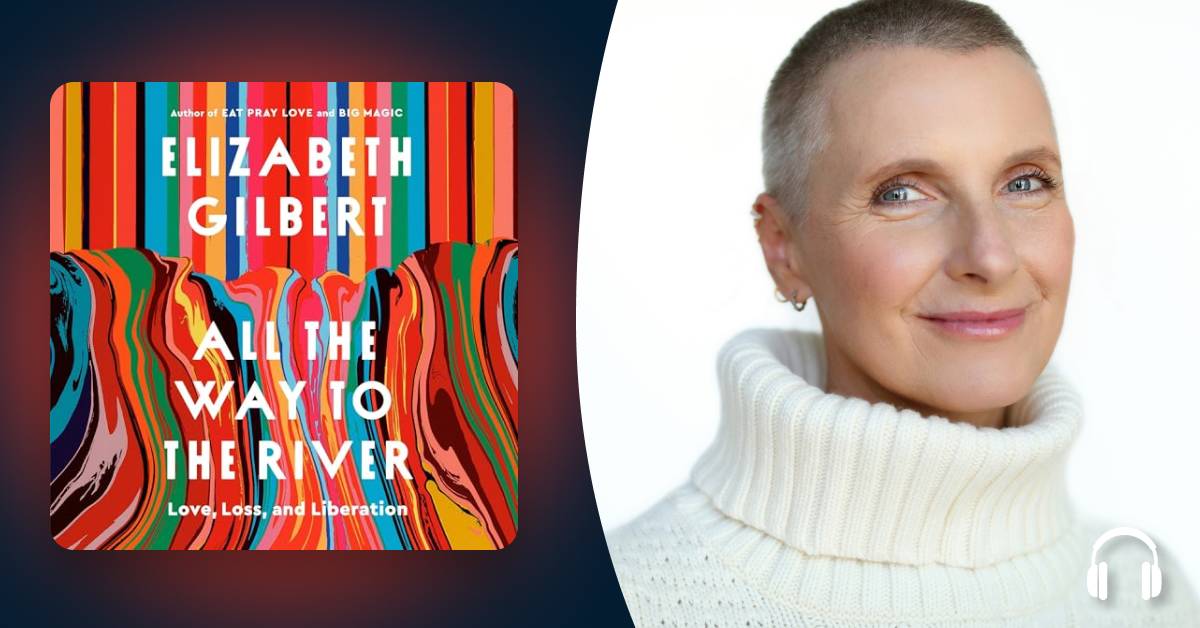

Kat Johnson: Hello, listeners. This is Kat Johnson, an editor here at Audible, and I'm so delighted to welcome the one-and-only Elizabeth Gilbert. She's the #1 New York Times bestselling author of Eat Pray Love, City of Girls, and Big Magic, among many others, and she has been a finalist for the National Book Award, the National Book Critics Circle Award, and the Penn Hemingway Award. Her new memoir, All the Way to the River, explores her life-changing relationship with the musician, filmmaker, and author Rayya Elias, who passed away in 2018. Liz Gilbert, thank you so much for being here.

Elizabeth Gilbert: Thank you for the introduction, Kat. I'm so delighted to get the chance to talk to you. I appreciate it.

KJ: Me too. And congratulations on the book, which I just finished last night, crying. [laughs]

EG: Oh.

KJ: It's a beautiful memoir. It's so emotional. It delves very deeply into sensitive topics of death and dying, terminal illness, grief, drug addiction, love and sex addiction, codependency, recovery. I knew this was going to be a tough listen, but it's also a total page-turner. It's very juicy and compulsive. It's often funny. And it's incredibly insightful and healing. It's also very different from your previous work, although it's very indelibly you. So, what does it mean for you to be putting this out in the world right now? And how does this release compare to previous ones, as this is your ninth book now?

EG: Thanks for all of that. Thank you. I smiled when you said it's also funny. I hope so. [laughs]

KJ: Yeah. I should mention—I don't want to get too much into spoiler territory because I did really enjoy the reveals of this book, but there are some moments that are really laugh-out-loud for me.

EG: [Laughs] The reason I laughed is because a hospice nurse who was working with us when Rayya was dying, you know, there's this particular kind of humor that can happen around the darkest, hardest, most tragic moments of life. She and I were laughing at one point, and I was like, “I'm so sorry that I'm laughing right now. You know, we're on this death watch with the love of my life, but I can't even remember what it was that made us both start laughing.” And she said, “Well, in the hospice field, we always say if you can't laugh at both life and death, you gotta get out of show business.” [laughs]

You know, this is just the only way that you can do this work. So, how do I feel as this book is coming out? I feel deeply calm and very relaxed, because I feel as though the really hard part for me is over. The hard part was the living of the story. There were sort of three levels of hard part: the living of the story, and then the processing, over years, of the grief and the lessons of that story, which included me coming into sobriety and working a 12-step program, which I still continue to work.

And then, how in the world to tell this story? A big question for me as I was writing the book was, do I have the writing chops to actually describe Rayya, who was such a particular person? Can I communicate what Rayya was, effectively, because she was so much of so many different kinds of things? And then, do I have the emotional stability and the support and the courage to go back and relive the most traumatic parts of the book again? And the answer to both of those questions, for a lot of years, was: “No. I don't feel like I can do this. I don't feel like I can do this artistically; I don't feel like I can do this emotionally.” But having done it, and taking the last two years to write the book, it feels like the biggest cosmic homework assignment of my life has been completed.

And now, I feel absolutely relaxed about putting this into the world. Weirdly maybe more relaxed than I've ever felt this close to book publication—just a kind of surrender of, well, here it is, and to the very best of my capacity, this is the truth. And the truth is always, once you can find it, a very relaxing place. That's one thing that I've learned over the years—like even difficult truths, I would rather sit in a very difficult truth than not be in the truth at all. So I feel very peaceful, and I also feel happy that people will know Rayya.

I mean, they had many chances to know her: she wrote her own memoir, called Harley Loco. She made short films. She made music. She loved being known. But my Rayya, the Rayya that I knew, I get to now bring that into the world, and that feels really peaceful.

"It feels like the biggest cosmic homework assignment of my life has been completed."

KJ: I love that, and that was my next question. The first pleasure of this memoir is just getting to know Rayya. Your writing makes her come through so vividly. And I came to love her, not over the course of the book, but pretty instantly. She's just such a force! But you had this kind of different experience where you didn't fall for Rayya, at least romantically, right away. You had almost two decades-worth of friendship that came first. So, can you tell our listeners who might not know, how you realized that Rayya was your person and your decision to walk with her, as the title says, “all the way to the river”?

EG: Listen, I identify—in my recovery and publicly, just to keep my life simple and transparent—as a sex and love addict. We can talk more about what that means and doesn't mean, but as part of my addiction, which has constantly and always been to use other people the way some addicts might use drugs and alcohol, I've fallen in love at first sight many times. [laughs] It's a very untrustworthy feeling for me to have. It's never really about love; it's always about uncontrollable need and attraction. And I did not have that experience initially with Rayya.

I met Rayya because she was my hairdresser, and then she became a social friend, and then she became a neighbor, and then she became a really good friend, and then she became my best friend, and then she became something that we just no longer had words for. And we just used to call each other, you know, “this is my person.”

And that took 13, 14, 15 years for that deep intimacy to grow between us. I was married at the time I met her, and I was married to a different man at the time that I fell in love with her. She had multiple relationships during that time with women. But when we found out that she had terminal cancer—and this pancreatic and liver cancer diagnosis that they originally gave her six months to live—it was no longer possible for me to hide from her, from myself, and from my husband that this is the person who I loved and needed to go and be with.

And that was how our journey transformed from deeply intimate friendship to a romantic relationship and a partnership—with the highest level of drama that you could imagine. Because we were running out the clock, you know, we've known each other all these years. We've both secretly loved each other for many years, and now there's this tiny amount of time, this window of time that we have to be together. What Rayya called the river, before the river of death would come, you know? And that journey did not end up being what either one of us had expected it to be. [laughs]

KJ: No.

EG: Not even in the length of time: It turned out to be 18 months, not six. And a lot happened in that time that was really traumatizing. A lot happened that was really beautiful and glorious. But the short version of the story is that Rayya was a drug addict who had long-term recovery from being a heroin and cocaine addict. And when the pain and fear of her cancer and mortality started to catch up with her, she picked all that back up again after, I don't know, 13 years of sobriety, and she returned to the lowest and most-degraded version of herself. And I returned to the lowest and most-degraded version of myself—which is a blackout, codependent, Olympic, world-class enabler, and somebody who throws herself away at people and calls that “love.” So that journey got dark, and not in the ways we were expecting. We were expecting the pain and difficulty of a cancer death, but not the much more soul-eroding and spirit disease of addiction to arise in both of us.

KJ: Wow. It's so interesting. I have my own experience with recovery and with AA, and I definitely remember early on being so flabbergasted by… I remember having a really elderly person in one of my meetings that wanted to just have a drink. And I just thought, “Gosh, you're at the end of your life, why does it matter almost?” And this book, more than anything, has illuminated that for me.

EG: Answered that question. [laughs]

KJ: Yes. I have no more questions. [laughs]

EG: If you ever were, like, saving up for when I get that end-of-life diagnosis, I'm going to go on that last bender, and that sounds good to you: The answer why maybe not to do that is contained in these pages.

KJ: It's contained here.

EG: [Laughs]

KJ: One of my favorite Rayya-isms that I can actually repeat because it is profanity-free, is: “The truth has legs.” I love that Rayya would say, “When everything else has blown up or dissolved, the only thing left standing will be the truth.” How did Rayya's reverence for truth and honesty inform the telling of this story, or even your writing in general over the years, if it did?

EG: Oh, what a great question, thanks for that. I can never hear that line enough. Okay, this is my Rayya. Everybody has their own Rayya, but the one who I loved, my perspective on her, how I saw her, was that her highest virtue—when she was sober and when she was in her sanity—was: I never met somebody more fearless in the face of the truth. Never. And haven't since. It was astonishing how quickly she could get to the center of a thing. Whether it was about her; whether it was about someone else; whether it was painful; whether it was frightening. She would sail her ship right into the teeth of the gale of the truth and land there as quickly as possible, because as she used to say: “It's where we're going to end up.”

You know, that's the thing about the truth—the truth has legs. It's the thing that's going to be left standing; it's where we're going to end up. And since that's where we're going to end up, we should just start there. Like, let's cut through all the drama that separates us from the truth, and let's just start with it and save a lot of time because it's where we're going to end up. [laughs] I had never met anybody like this.

That's what made us such close friends... At our best, we each had a fundamental fearlessness that the other lacked. And I lacked that fearlessness of truth; truth to me has always been the scariest thing in the entire world, the thing that must be hidden and manipulated and dodged and avoided at all costs—until everything does blow up.

And so, for years, Rayya was my coach and counselor on: just open your mouth and say the thing. Or ask the direct question or receive the painful answer. But the truth is your friend. She had no fear about it. Where she did have a lot of fear was in her creative life, where she always felt like she was failing, where she had a ton of insecurity. And I am kind of fearless creatively. Like that's the place, you know, the Lord doesn't give with both hands, Kat, you know.

KJ: Yeah.

EG: But that's a thing I have: I will risk any creative expression. I think we all are allowed to do that. It's something that's really easy for me.

And so, I was creatively coaching her through the years to make her art, to write her book, to do her music, to put herself out there in the world at that vulnerable level. And when we were all firing on all our cylinders, and in our health, that was the magnificent thing between us: The way she supported the parts that I was wavering about, and the way I supported the parts of life she was wavering about. And we brought out the best of each other until we didn't. Until, in our darker sides, we also brought out the worst of each other, as it turns out.

There's a reason it took me seven years, from her death, to write this book. It's because I couldn't figure out how. It's such a complex story. And there were things in there that were going to have to be revealed about both of us that I wasn't sure I felt comfortable with the world knowing about her or about me. And the whole beginning of this version of the book I wrote… I wrote a fictionalized version of it that I never showed anyone, like trying to kind of write around the truth without writing the truth. I wrote a version of it that was just poetry. Like, I'm going to just speak in really poetic, abstract language around the feelings of this without actually telling the story of this. [laughs]

KJ: Right.

EG: Maybe I can get away with it, you know. In both cases, I'm like, "Maybe I can get away with not doing the thing that Rayya would've said to do."

Ultimately, the thing I did say to do in the first chapter of the book is essentially a mystical visitation where Rayya came to me and was like, "Girl, write this book." You know, and write it in her words, "Go full punk rock with it. Lay it all out on the table. Tell the absolute truth. That's the only way to do this."

So yeah, that courage that she lent to me, even from beyond the grave, was finally the motivating factor. And then, once I started, it really... You know, this is one of the lessons I came to Earth in this round to learn. There's only one way to do this, and it is to tell the truth.

KJ: Right.

EG: And the sooner you get to it, the better you're going to feel—even when it's terrifying.

KJ: And you had that incredible experience later in the book, when you're working on your recovery and you met some fans in your support group. And you just made the decision, like, it's more important for me to recover than to keep my privacy. So that's kind of related as well.

EG: Yeah, I need my recovery more than I need my dignity, my public image, my privacy or anything else in my life. Because without my recovery, I will lose everything else in my life.

KJ: Right.

EG: But only always.

KJ: Only always. Yeah, no big deal. Your work often has these sticky ideas that people latch onto. In Big Magic, I loved this theory that ideas are alive, that they have this conscious will and actively seek people to manifest them. I totally subscribe to that, and now I totally subscribe to an idea you posit in this memoir, which is the curriculum of the Earth School, and this idea of the “cosmic boardroom.” Why don't you tell us a little more about that, where it came from, and what it means to you?

EG: I'm not the inventor of the Earth School idea. Actually, it's something that runs through many spiritual and religious traditions. The concept that Earth is a school for souls is especially prevalent in Eastern theology, but it shows up in Western consciousness as well. But this concept that you come here deliberately to take form, perhaps not for the first time, perhaps not for the last time, definitely for the first time in this particular form—whatever form you've embodied in this time. And you've come here because you're very courageous as a spirit, and because you want to evolve, and you want to learn. And this is a radically challenging school.

"That journey got dark, and not in the ways we were expecting. We were expecting the pain and difficulty of a cancer death, but not the much more soul-eroding and spirit disease of addiction to arise in both of us."

It is for everyone. But you can learn stuff on Earth faster than anywhere else in the universe, and typically through experience. And there are certain experiences that you can only have embodied on Earth; and they are extraordinary experiences; and they are challenging; and they're devastating; and they're heartbreaking; and they're beautiful; and they're pleasurable. There's all these experiences to be had. And you choose—with your spirit counsel back in the boardroom—exactly the experiences that you're going to have in this life that will most directly and efficiently give you the lessons you need to transform and to grow. And the Earth School model of seeing life that way, it makes a lot of sense to me because, one thing that I appear to see, you know, trusting my perceptions as much as I can—which is limited.

KJ: Yeah.

EG: But I don't think there's anybody—and I don't care how much privilege somebody may appear to hold—who will reach the end of their life on Earth and say, that was easy. You know? That was a breeze, that was so easy being in human form. It's not. It's really hard. And if you really are an accelerated student, you might have picked an advanced curriculum. [laughs]

KJ: Right.

EG: Because nothing will bring you faster learning than suffering and pain. Which is not to say that you should seek out suffering and pain. I think where the Germanic Romantics made a mistake was sort of the “Goth version” of, like, I'm going to actually go seek out the most amount of suffering that I can. First of all, you don't have to: The curriculum's been established. The suffering will find you. It knows your home address. You know what I mean? You don't have to dodge it, and you don't have to seek it. It's coming, and it is going to be what it's going to be.

But how quickly you can move from a position of horror and terror and fear and resentment, and wanting to run away from this thing, to the question: What might be in this for me? Why might I have designed the video game this way? What am I being asked and invited to learn from here?

The faster you can kind of get to that question, I think the quicker you can get out of victimization, blame, and a kind of powerlessness. Not the good kind of powerlessness that comes with admitting addiction, but that sort of—everything's happening to me, and I'm just being battered by the storm of life.

The Earth School model suddenly becomes like, “Oh, this is a really interesting class, I wasn't expecting this one. I forgot I signed up for alcoholic parent.” You know? [laughs] I forgot I signed up for family estrangement. I forgot I signed up for living in a time of war. I forgot I signed up for losing the person I love the most. I forgot I signed up for horrific physical challenges and illness. Like, wow, okay.

KJ: Yeah.

EG: Having acknowledged that I signed up for this, where's the lesson? How do I graduate from this one with the most amount of grace?

KJ: Right. And sort of related to that, you say that you and Rayya manifested these different kinds of addictions, but they both kind of stemmed from the same place of deep spiritual sickness. I totally related to that, and the idea that having one kind of addiction opens the door to understanding and also being vulnerable to all the other ones. That spiritual sickness runs through our society, and I wonder, do you think to some extent, we all suffer from addiction stemming from spiritual disconnect?

EG: Gosh, that's a big question. I feel it looks that way to me, you know, but I also have to hedge that by saying, I have lots of experiences of life of something looking a way, and then it not turning out to be so.

KJ: Right.

EG: I will say that addiction has been called the God-sized hole. And I use the word “God” carefully, because I know that that's a very triggering word for a lot of people. And, also, a word that has been used to abuse a lot of people. And it's a word a lot of people just simply can't stomach and don't want to and shouldn't have to.

But what it points to is where in you is there a vortex of emptiness that is so profound? The literal definition of profound, in terms of deep, that nothing can reach the bottom of it, that nothing can fix it, that nothing has been able to heal it. That everything you have tried to throw at it, to medicate it, to numb it, to make it go away, to heal—it has not worked. And the reason it's called a God-sized hole is because God is a good catchword phrase for “that which is infinite.” You know? So, what is the infinite hole and emptiness and vacancy inside of you? And what have you been using to try to survive it? And how's that been going, you know? [laughs]

Like food, shopping, money, sex, power control, the illusion of control, drugs, alcohol, cigarettes, gambling. What are you doing to get out from that thing? And every morning, you wake up and that vacancy is still there. That's a spiritual sickness. And we live in a culture that has masterfully solved all material and all longings to be sated immediately in our culture—more than ever in history. You have a want, you have a need, you can get that thing fixed and filled immediately. There's an app for that. There's a drug for that. There's a something for that, you know?

The tricky thing about all of those wants and needs—and I've heard this described as the acquisition treadmill—the reason we are living in such a time of mass addiction is because all of those things work to make you feel better. We wouldn't do it if it didn't work. If sugar didn't make me feel better, I wouldn't use it. If caffeine didn't make me feel better, I wouldn't use it. If alcohol and drugs didn't make me feel different and better, I wouldn't use them. Like, money feels good, all this stuff feels good.

KJ: Right.

EG: But it passes, you know. It gives you this dopamine hit. It gives you this endorphin rush. It gives you this feeling of security, this feeling of power. And then it ends. It cycles out, and it comes to an end in a short or longer amount of time. And you're still left with the fundamental emptiness that was feeding that urge at the bottom that now is crying out like a baby in the night to be fed again. You know?

KJ: Mm. Mm-hmm.

EG: And so, it becomes this treadmill where it doesn't matter how hard you're trained, it just doesn't work. And I've also heard all addiction described as about as satisfying as hijacking a revolving door.

And so there's this enormous energy expenditure that you're doing to try to get all these needs and wants and urges met, and you're still in the revolving door. And the only thing in my experience that can fill a God-sized hole is God. And by God, again, I mean the infinite mystery. The other thing that is infinite is the only thing that can fill an infinite vacancy. It's the only thing I have found—and a lot of people in various kinds of recovery have found—that will still that rampant ravenous hunger and quiet it.

The quiet that comes with that is what they call serenity. And one of the things I write about in the book is about being an excitement addict as well, and an adrenaline addict, and a novelty addict. Like, I want the new thing; I want the biggest thing; I want the next thing; I want the thrill.

Somebody taught me very early on that addiction to excitement, that excitement and the need to be overstimulated, is actually the sort of flipside of boredom. And boredom and overstimulation are both signs of anxiety. They both equal anxiety. I can't sit in myself, so I need to be super-stimulated in whatever kinds of ways. And if you don't know serenity, if you've never experienced serenity, the only thing on the menu is anxiety or boredom. So, serenity is the thing I never had felt.

KJ: Right.

EG: And that, to me, can only be found through spirituality. That's an ancient idea that runs through a lot of cultures, that wasn't invented by AA in 1939. That is a deep, ancient-wisdom thing that says, the thing you're looking for that you think is going to make you feel better is within you. And that has to come from a spiritual place—or else it's never going to satisfy you.

KJ: I wondered about the love and sex addiction of it all, and particularly the codependency, because I feel like it's hard to see when you're inside a relationship. I loved the motto you provide, I don't think you wrote this one either, but it's, “You break it, we fix it.” I was wondering if you could explain a little more about what codependency is and what kind of advice you might have for others in those kinds of relationships.

EG: So, I'll be careful because I'm not a psychological expert. Also, I’m going to be careful about being in the advice-giving business. So, I think the best thing for me is to express how it manifests in me, and to just keep it on the “I”—as we say in the rooms—and keep it on myself and my own lived experience.

So, how codependency runs through my system is it's a deeply sincere, earnest, and totally insane idea that if I can make you be okay, then I will be okay. So the way that I'm going to finally feel all right and safe is if I can fix your life. Because again, going back to anxiety, I can't bear watching you spiral because it sends me into enormous fits of terror and anxiety.

"There's a reason it took me seven years, from her death, to write this book."

And rather than going off and sitting in a room alone in meditation with my terror and anxiety, or praying for relief from that, or learning how to monitor that in myself and learning how to take care of my own nervous system, I hop out of my own existence and nosedive into yours with a whole bunch of plans for how to make your life good. You know, I'm going to fix you. And codependents are really attracted to addicts because there's a lot to fix there, a lot to fix, manage, control, and rescue in a person whose brokenness is so evident and obvious.

One of the other things I quote in the book, something that my uncle—a family member who's also in recovery—said to me: How to kill a codependent is you lock them in a round, empty, windowless room, and you tell them that there's somebody sitting in the corner who's suffering and needs their help. And then you watch as they literally run themselves to death trying to find the person who needs to be saved. The thing that's super tricky about codependency is that you can really mask it behind: “I’m just a really good person.” [laughs]

KJ: Right.

EG: “I’m just a really good person. I’m just a really good person. I’m a really kind person. I’m a really compassionate person. I just want to help.”

KJ: Mm-hmm.

EG: I think I put this in Big Magic, that this British... I can never remember her name who said it, but she said, “You can always tell people who live for others by the anguished expressions on the faces of the others.” Right?

KJ: [Laughs]

EG: And what's happening is that what you're doing is you're pouring your life force into somebody who may or may not even want to change. One of the lessons I've been taught as a recovering codependent is, don't care more about somebody else's life than they do. That might seem really simple, but like, look around. How many people are you up worrying about at night, who aren't taking care of their own life? I had a really great sponsor who said to me one time—this was a radical moment of learning for me—she's like, “I’m not throwing shade. I'm just genuinely curious. Are you aware that other people can take care of their own lives?”

And I was like, “Uh, I see no evidence to support that.”

KJ: [Laughs]

EG: You know, like, “All I see are people, like, flailing.” And she's like, “Well, do you literally not know that?” And she said, "It doesn't mean people will. It doesn't mean people will take care of their own lives, but people can take care of their own lives if they decide to. And if they decide not to, why are you taking care of their life?”

This is what I've done my whole life, one of my earliest pain-evasion survival tactics as a child was to be like, if I can make these people around me be okay, then I'll be okay. And it didn't work when I was 4 years old, and it didn't work when I was 15, and it didn't work when I was 30, and it didn't work when I was 40. It doesn't work.

So it's a tough one to get away from because it's so tempting. I mean, that's another one of my drugs is like, let me get the high of fixing your life. And it's a wonderful way for me to avoid my own. And so much about recovery is about not avoiding your own life anymore.

KJ: Absolutely. So, I have to ask you about the audiobook. I always love your narration. This one in particular is so personal and emotional. Was this a hard book to read out loud? Did you have any feelings about the recording process that you might want to share?

EG: This one, I definitely wanted to read. I read all my memoirs. I don't read my novels because I feel like they need actors, because of all the different characters, although this book has plenty of characters, too. But, yeah, this one, I knew I was going to read it. And the request that I made to Riverhead, my publisher, was: “I'll do this, but I can't do this in an antiseptic recording studio in Midtown Manhattan. I can't. Like, I can't go back into the Ninth Circle of Hell of this story with, like, just some dude bro engineers sitting around, you know, nameless people. I can't." [laughs]

KJ: Right, right, right.

EG: It’s so intimate. And I brought to them a proposal, and I was delighted that they went with it. So, one of Rayya's best friends—and also a recovery fellow of hers—is this music producer named Barb Morrison, who lives in the same town where I live and where Rayya used to live. And Rayya recorded music with Barb for years; they worked together. And Barb's got a studio in their home. That's one of my safe places. Barb's a dear friend of mine, and their living room is one of the places in the world I feel really safe—in this old farmhouse in rural New Jersey. And Barb knew Rayya before I did. I mean, Barb knew Rayya from the rooms, from repeated relapses. There was a real intimacy there. And that's who I wanted in the room.

KJ: Mm-hmm.

EG: I wanted somebody who knew all the Rayyas: the amazing Rayya, the funny Rayya, the trustworthy Rayya, the incredibly untrustworthy Rayya, the repeated-relapsing addict Rayya, the hustler. I wanted someone who knew those stories and who knew both of us. So, we sat and did it in the living room of Barb's house. And that turned out to be really challenging because Barb's a rock ‘n’ roll record producer. I thought I had a silent studio until it came time to do an audiobook—because it's a different level of silence that's needed. And Barb's like, “It's one thing to be quiet enough to record a guitar solo; it's another thing to be quiet enough to record a book.”

We found out that Barb's house is not as quiet as we thought. [laughs] There were helicopters and airplanes going on overhead, and birdsong outside, and dogs barking. There's a farm across the street where they were building a barn and motorcycles driving past. And then the noises of the house and refrigerators turning on and air conditioning units. We had to stop recording so many times that it became comic. But it also was kind of beautiful because it made us slow down.

KJ: Mm-hmm.

EG: We’d be in this deeply emotional part of the book, and then an airplane would go by, like a private, loud airplane would go by. We also found out—we didn't know this—that Barb's house was right in the middle of a flight path of a local airport. Like every 10 minutes, there'd be another airplane going by. So we would have to stop, and at first, we were frustrated by it, but then we started to take those stops as meditations and we would all of us—Barb and their sound engineer and myself—just sit in silence for five or six minutes and feel what we had just read. And then, once that stillness came up again, Barb would be like, "Okay, go." And then it's like it would drop us into deeper and deeper levels of stillness and intimacy.

KJ: Wow.

EG: And I think that really informed how the book sounds. It's not a book you want to read out loud quickly. And you don't want to move too quickly through those chapters. My friend Rod Bell always says, "Don't move too quickly through the experiences of life that have the most potential and capacity to transform you." And so, it took us more days than we planned, but it was transformative to do it at that pace.

KJ: Wow. It doesn't sound like an ideal recording scenario, but for you, it ended up being just the right thing.

EG: For sure, yeah.

KJ: I have kind of a curveball question for you, but I'm interested in what you might think about it. In your professional life, your early writing leaned into men and more masculine topics, but then with Eat, Pray, Love, you gained much more of an audience with women. Similarly, in your personal life before your relationship with Rayya became romantic, you'd been in relationships with men. And in All the Way to the River, you mentioned this idea of the “marriage benefit imbalance”—which is something that my girlfriends and I talk about a lot. There's a lot of talk about the manosphere and the idea of masculinity being in crisis. Given all that, I wondered: what's your take on what's going on with men these days?

EG: I'm not at all interested. [laughs]

KJ: You're just not interested. Interesting, that's fair.

"I was married to men, I was in relationships with men. I was constantly trying to understand men. And I think I've given enough attention to men."

EG: And I say that, actually, with a lot of love, because I have always loved men, and I've always felt pretty comfortable around men. And I, for years, as you noted, wrote books [about them]. I wrote a whole book called The Last American Man, where I went into a deep study of masculinity, and American masculinity in particular. I wrote for GQ magazine for five years. I wrote for Spin magazine for five years. I wrote for Esquire. I wrote for men and about men, and I thought about men all the time. And I was married to men, I was in relationships with men. I was constantly trying to understand men. And I think I've given enough attention to men. [laughs]

I think they are in crisis, and I think that's a them problem. And I think women have been trying to help men for a really, really, really long time, and I think that it's the moment now where men need to figure themselves out. It's so easy when a woman loves you to just collapse into her care.

It's so easy to just be like, “I don't have to do any emotional labor because she does all the emotional labor. I don't have to make myself feel better because she's going to make me feel better. I don't have to keep up any relationships with people because she'll do that. I don't have to stay in touch with my family because she will.”

One of the things that is really interesting is, typically in man-woman, cisgender marriages, women do really well after divorce. I mean, they delay it for a long time because there's this tremendous fear of hurting the other person; there's a tremendous fear of loss. There's a tremendous fear of being alone in a culture that tells women that they can't be alone.

But, actually, the reality is women thrive after divorce and men tank. And part of the reason they tank is because they haven't been taking care of themselves at all, and they haven't been taking care of their relationships and the networks around them at all. They've been letting a woman do it.

KJ: Right.

EG: So, women have sort of been doing the lifting for both, in these cases. And a lot of women after divorce feel this huge relief of, now I'm just taking care of one person, not all the people. So my attention's not on men, and I actually think that's beneficial for everybody. I think it's beneficial for them. And I think it's beneficial for me. Certainly it's beneficial for me. Because I've poured myself into a lot of men.

Everything that I'm doing now is about uplifting women's lives. Encouraging women, supporting women; it's where all my money goes. It's where all my creative attention goes. And then there are men who show up for what I'm offering, which I think is really cool. I teach these creativity workshops and sometimes there'll be 1,000 people in this weekend-long workshop, and there'll be five men. I always notice them, and I always call them out in this really loving way and say like, "Just want to let you know that I see you. And any man who wants to be here with 995 women, we love you." Like, "We love you already, and we're glad you're here. We hope you feel safe and comfortable here—and don't make a woman here take care of you.” You know?

KJ: Right.

EG: Like, the women have come here to take care of themselves, so, you know, look after your own emotional health and show up for everything we have to offer. But nobody's going to get well in this world as long as men continue to use women as their buffer for everything and as long as women continue to do it.

KJ: That is a great idea to end on, and I love that answer so much. Before we go, I'm wondering if there's anything that you're working on—upcoming or in the works—that you're excited to share with your many, many fans?

EG: You know, the thing I'm most excited about that I've been doing for the last two years is on Substack—which a lot of people still don't even know what Substack is…

KJ: Ah, yeah. It's the best place on the internet, right? [laughs]

EG: It's the best place on the internet. It's giving, like, internet 20-years-ago vibes. Essentially, people are creating these newsletters that are—it's a return to the blog, you know?

KJ: Mm-hmm.

EG: And it's a place where a lot of people, myself included, have been going to try to communicate across the internet in a way that is not guided by the algorithm and social media. So I started a Substack newsletter two years ago, called Letters from Love, that is a place where I'm teaching and sharing with people this practice that I've been doing for years to rewrite the self-hatred narrative in my own mind, and the one that culture reinforces all the time. I write myself a daily letter from the spirit of unconditional love. And that's where I go to for guidance; it's my higher power. And it's every day I do it, and I ask, "What would you have me know today? What would the spirit of unconditional love—if it were embodied and speaking to me—want me to know?"

And then I write that letter, and it's transformed my life. And I never knew whether it was teachable, but I've gone there to Substack to teach it, and it is indeed teachable. We've got 200,000 people in that community who are doing this practice on a daily and weekly basis. We bring in special guests once a week to write themselves a letter from unconditional love and share it, and it's just such an incredible community. I can say, without any hesitation, that the Letters from Love newsletter is the kindest corner of the internet, with the amount of love and support that people are giving to one another there. It's a really safe place, and it's becoming something like a real garden of love and grace and healing. So, that's the thing I'm most excited about right now.

KJ: That's so awesome. It's so good. Everybody go to elizabethgilbert.substack.com, Letters from Love, it's lovely. And you're lovely. Thank you so, so much for this; it's such a great conversation.

EG: Thanks, Kat.

KJ: And I'm so excited for your book to be out there and everyone to listen to it because it's wonderful.

EG: Oh, I appreciate it. Thanks for giving me this opportunity and all blessings to you on your journey.

KJ: Thank you.

EG: What a wonderful interview and such great questions. Sending a lot of love to you and to everyone.

KJ: That means a lot, thank you so much. And listeners, All the Way to the River, written and read by Elizabeth Gilbert, is available on Audible now.