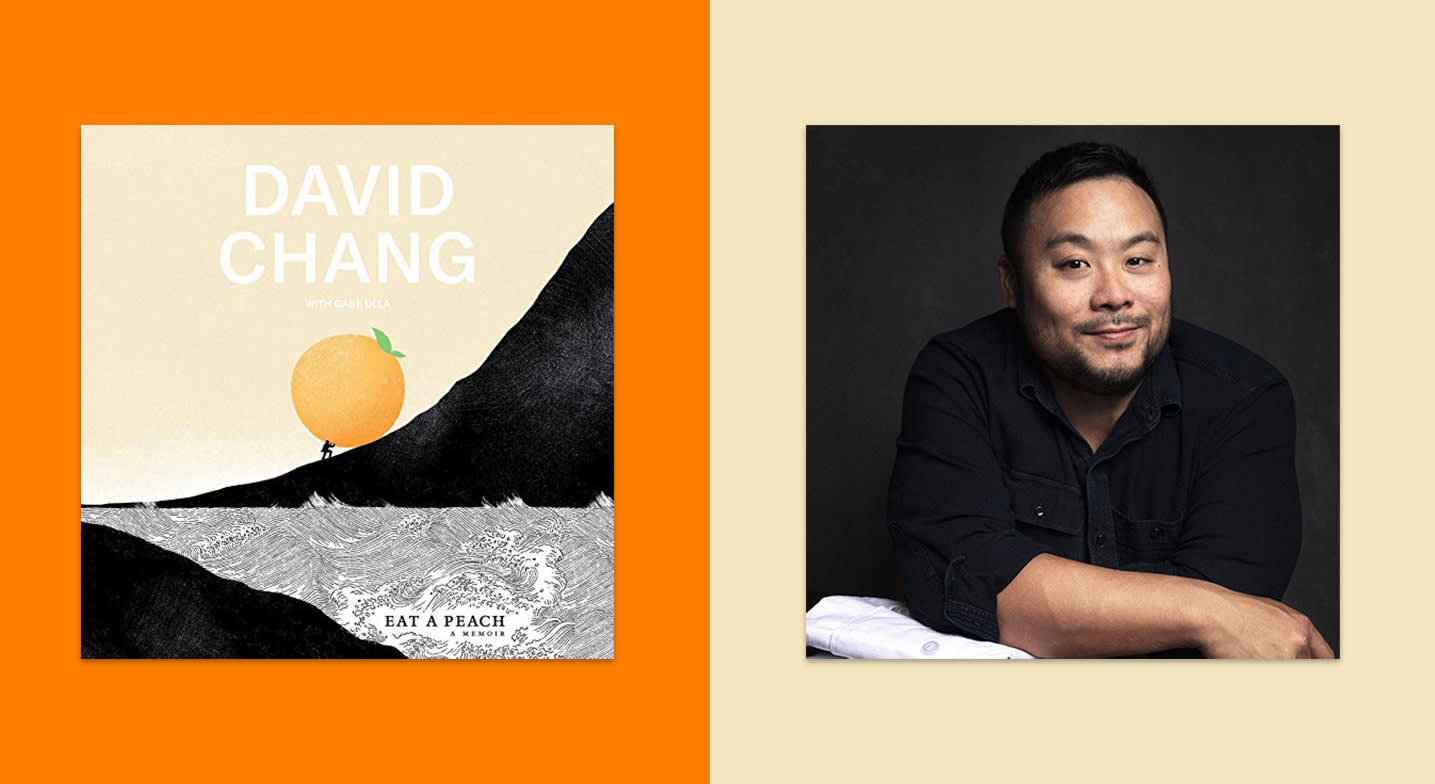

Kat Johnson: Hi, this is Audible Editor Kat Johnson, and I'm here today with David Chang, who is best known as a world-famous chef and tastemaker. But his new memoir gives listeners even more to dig into on the subjects of mental health and entrepreneurship. Eat a Peach explores Chang's journey from his roots as the child of Korean immigrants and young upstart chef to the top of the global food chain, with some ups and downs along the way. I'm so excited to have you here with us today, Dave. Thank you.

David Chang: Thank you for having me, Kat. Real pleasure.

KJ: Thank you. This memoir is very candid and it's very surprising. I couldn't wait to listen to it because I’ve followed your career and eaten at your restaurants since you opened the first Momofuku Noodle Bar in New York in 2004. So, I was really excited to understand the David Chang vision.

But what I loved when I started listening is it's so much about you getting to know other people's perspectives and really deeply reflecting on your experiences and kind of rethinking them. Is that fair to say?

DC: Yeah. I mean, I think you did a better job of summarizing it than I ever could. It's weird to think about the book now that it's done and it's out there, but there are a lot of buckets that it covers. I'm constantly reflecting upon what my life has been. And even though the book is done, I'm still like, it's not done. It's just the beginning of sort of reevaluating everything.

KJ: Well, I'm going to try to stay away from food metaphors, but it's going to be like a stew. We're going to be jumping around from topic to topic, if that's okay to do.

DC: Sure.

KJ: You opened Momofuku in 2004, at a time when American cuisine wasn't generally as spicy and wild and fusion-y and delicious as it is now. And you took on a lot of risk in opening the restaurant. Any kind of restaurant in New York is a risk, but you didn't have really any experience. You were very young. And at the time, people's association with ramen was kind of like instant noodles, dorm-room kind of food.

In retrospect this was a brilliant idea, but this was actually a really dark time in your life.

DC: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

KJ: Can you explain a little bit, the relationship between this big risk you were taking and where you were in your life?

DC: When I was 26, I would probably not be able to comprehend that one day I'd be able to talk about whatever happened. Partly because at that point in my life — and it was something that was a long period — I just felt I was on a one-way ticket and I had had a pretty unspectacular life up until that point. A lot of unfulfilled promise.

I was going through what is now probably the worst period of depression in my life, where there was a lot of suicidal ideation. And it wasn't just that it was an existential dilemma and a dread in trying to find meaning in what I found to be a meaningless world and my place in it. I felt I needed to come to a decision on what were two options.

One is, I do something with my life that I never thought I should do — or I end it. And you get that reductive. You have that kind of clarity, it's unfortunate clarity. You begin to be like, "Well, I'll try this or that because I already know what is behind door number two."

I'd never really even thought about opening a restaurant up until that point. Opening a restaurant to this day is one of the hardest things you can do. So, I think I wanted a challenge that I was supposed to fail at, and failure just didn't become a problem for me. The idea of failure was like, who cares?

So it really became "I don't care anymore, as long as I don't hurt anybody but myself in doing a business." If I had to declare bankruptcy, well, that's not as bad as ending everything anyway.

Momofuku became an exercise in the opposite of what I thought I might do. It was a weird way to start a restaurant. It was a weird place to be, a very sad place to be. There were a lot of things going on in my life, and Momofuku became therapy in addition to the therapy that I began with a psychiatrist. So much of who I am today, and what Momofuku was, is intricately intertwined with my mental health.

Cooking saved me and really kind of hurt me simultaneously, because it gave me purpose. It gave me meaning in a world where I couldn't find meaning.

KJ: In the book, you talk about your bipolar diagnosis. And I know you've had manic periods where you're really creative. But it's interesting to hear you say that depression really fueled your addiction to work. Because so often we think about depression as like, lying in bed and not being able to do anything, but you were able to be incredibly productive.

Is that fair to say? And do you think there's anything to the idea that we have this persistent myth, that mental health and creativity are intertwined?

DC: Yeah. The funny thing is I had to be yelled at my entire life to work and then all of a sudden, I think I found a work ethic in cooking. So, that was a little bit of a calling and cooking saved me and really kind of hurt me simultaneously, because it gave me purpose. It gave me meaning in a world where I couldn't find meaning. Cutting something properly, cooking something properly, making it go to a customer, and them having a delicious meal, all equated to something that I could understand, that I had control and agency.

And then starting a noodle bar in 2004, that feeling got amplified on steroids, because the work that I put into it was the only thing that I could depend on. So, work became everything and is still, in many ways, everything for me. Out of that, if I really dig deep with all the work I've done with my psychiatrist, the work really masked pain.

It was a temporary sort of reprieve from whatever I was going through. And by focusing on that, I never had to really deal with my own problems and it allowed me to sort of delay anything.

The work itself, most of the time, was painful. It was so hard and that's something I'm still trying to unravel, that nobody wants to feel pain. But I tend to gravitate to feeling pain physically and emotionally because that has actually never failed me either. And that's a weird, terrible thing to say and to think about, but it's true. And the only way I can get better is by acknowledging it. That is what I'm trying to sort out right now, is all the work that you put into something, the workaholism.

And in the book, I say that it's sort of a last accepted addiction in this country. And I do believe that's the case. It is seen as a good thing. But if you pour yourself into that, you can stunt the development in other parts of your life as well, just like any other addiction.

KJ: Well, of course for you as the business owner, it's one thing for you to be all in, guns blazing, but then to hold your employees up to the same standards is another story, right?

DC: Yeah. Which is something that I'm still trying to unpack as well, because my meaning that I derive from work is a very specific thing. And it's almost like a religious thing. I literally can have an understanding of what I'm supposed to be and what I'm supposed to do by the most minuscule things in a kitchen. And it doesn't even have to be in a kitchen. It could be outside of the world, but so much of my life was abandonment or feeling conditional love or feeling let down.

And again, if I just write a piece of tape properly and label something, that little act was so meaningful to me. Not that I was conscious of it, but the aggregate, like I have agency and control and because doing things right in the kitchen saved me and gave me purpose and meaning. It was like they were my best friends. It was my family. It was a thing that, again, all of my life finally made sense. So if somebody didn't care about it as much as me, I took it as an attack on me. It's what I've learned is affective dysregulation and that's a whole other story, but it's debilitating.

I'm constantly striving to find what balance is, work/life balance. It's clear to me that however I worked in the past will not work moving forward. And in some ways the next chapter of my life is systematically deprogramming anything that I thought was good for me.

KJ: I wanted to talk to you about the experience of narrating the book. There was something that really struck me. I've never heard anyone do this in a book or an audiobook, but you actually kind of rewrote it as you were going.

You say, "I thought I'd be fine revisiting this for the audiobook, but I find myself pissed that I have to rehash it." And then as you're telling this story, you start contrasting what really happened with your perspective on it now. Can you tell us a little about how that worked? Because I've just never seen that happen before.

DC: Right, and that's the difference, I think, between the book and the audiobook. I do believe that while they're the same thing, and you're fully aware of this I'm sure, but they're also two different things, right?

That was tricky for us to figure out. How do you talk about footnotes? How do you voice change in words, when there's a chapter where it's a revisionist history of the things that I wish I said and did vs. how they appeared in my life as really traumatic and sad, or sometimes an inappropriate or boneheaded response.

Now, at the age of 43, I have the ability to say, "No. This is what the response should have been." And I thought the audiobook doing it that way was a little bit more effective than even writing it down, because it's more conversational. It's like, "Hey. It was this way but man, I'm an idiot. It should have been this way."

I was nervous that it wouldn't translate but I'm really happy that you liked it. It came across as conversational. It came across as something that is organic and that's what exactly it was.

KJ: Well, I love your podcast and I love this audiobook, and I love to see these fusions happening. So I think that's a cool direction for you to go in and for anyone to go in.

DC: By the way, recording audiobooks, it's not easy. I mean, I have the highest respect now for anyone that is good at this, because it is so difficult, and shout-out to all the producers who have to do this. I don't think anyone understands the meticulous work that has to go in on the sound engineers. I have no idea how they do this and my hat goes off to them because I am totally in awe of their work ethic, because it's unbelievably hard.

I don't know how to articulate it. Other than, I don't know how an audiobook gets done. It seems impossible. It seems simple on paper, but man, it is not easy to do for anybody.

KJ: But you did it! But set the scene for us, because your book was one of the ones that got kind of pushed out because of the pandemic. When did you actually record?

DC: I was supposed to record in April in a studio in New York, and now I'm in Los Angeles. Because of social distancing and because I had podcast equipment, we decided to test the sound and recording capabilities, and it worked out that I was able to do it here instead of having to go to something that might not be as safe during COVID.

So, that was difficult because usually you're able to do it with the engineer and it's live. And it's just like most things in a COVID world, it's not as easy without human interaction for whatever reason, but it worked. I had some amazing sound engineers and amazing producers who were with me I don't know how many hours for two weeks. And we got it done.

It was a lot of work. I'm happy that it came out. It did get pushed back, unfortunately. It was supposed to come out in May and now it's stuck in a glut of Donald Trump books.

KJ: I know, but we need a reprieve. We need something else to listen to, so we all appreciate that.

In addition to being a memoir, this also functioned as a little bit of a business, how-to guide or in some cases maybe how-not-to. But I really love the section you have called “33 Rules for Becoming a Chef” also because I'm obsessed with Jerry Saltz's book, How to Be an Artist, which you were inspired by. Can you tell us a little about that and what you liked about Jerry's approach?

DC: I am so fortunate to call Jerry Saltz a friend, and the fact that he wrote this book off an article he wrote for New York magazine, and you should go out and buy it because it's not just about being an artist. I think it's being creative, being an independent thinker and having the courage to go out in the world and put your ideas to paper or make a building or do any kind of creative endeavor.

I love it so much. He has so much insight. And we did a couple of podcasts with him and I was like, "I think your '33 Rules' is more appropriate for the culinary world than anyone realizes." And he was like, "Why don't you just make one for chefs?" And I was like, "Fine. I'll do it."

And that's what we did. It was based on his 33 Rules and it is not all rosy. Basically most of the rules are trying to tell you do not become a chef, do not become a cook, until you have no choice.

We've really learned how to think about someone who has an addiction problem. It's still a process that we're learning to talk about. And we're in the beginning stages, still, of destigmatizing mental illness and all of its facets.

And that sort of fulcrum. That point where, if you haven't been there, then it's maybe not the right job for you. You have to have this compelling feeling that you cannot do anything else but to do that. It doesn't have to be cooking. It can be anything. And that's what you should be doing.

Oftentimes, whatever you choose to do flies in the face of conventional wisdom. And people might tell you it's a bad idea, but if you still feel like you have to do it, then you do it. And I think the 33 Rules sort of gives you not a play-by-play, but a breakdown of what might happen in your career over 20-plus years.

KJ: You have some really great business advice in the book. My favorite one is: "Organic growth means having no strategy." And I'm going to use that in meetings for the rest of my life, because then I don't have to write any strategy.

DC: It's true. It's true, Kat. Everyone's like, "Organic strategy is such a cool thing." Well, if you try to plan an organic strategy, well, that's not organic. At all.

KJ: I was a devoted reader of Lucky Peach, and I loved the way the design kept changing. We touched on this before, but you went from not having experience to having this very, as we said, one-way ticket, guns-blazing, risk-oriented approach, and now you're more mature in your career. You've got a family, you've got stakeholders. How do you balance — or don't you? — the approach that's worked for you in the past?

DC: I don't know if the word "balance" would ever be something that should describe whatever I do or how I live. Yet it's something that I'm in constant search for. I'm constantly striving to find what balance is, work/life balance. It's clear to me that however I worked in the past will not work moving forward. And in some ways the next chapter of my life is systematically deprogramming anything that I thought was good for me.

I've stepped down as decision-maker of Momofuku. There are a lot of things that I've done. I don't have to be in the kitchens. I'm still involved, but I mean, my words don't carry weight anymore.

And part of that was a process to step back and reevaluate and add value in different ways. It's hard to teach happiness in your work. It's hard to teach, I think, true hospitality, if you don't know it yourself, and that's what I'm trying to learn.

KJ: You talked about your struggles with anger in the memoir, especially in the kitchen. It's actually kind of scary, at times you say you've almost lost consciousness. The persona of the angry chef is one we're very familiar with. Do you feel like the cultural myths around this "bad boy chef" mentality enabled your behavior?

DC: No. I don't know if anything enabled it. If anything, my behavior I take full responsibility for, and I don't think you can blame anyone else. I have agency, and it doesn't mean that I can rationalize it and I can understand why it happens, but ultimately when you reflect upon that sort of lone genius being a tyrant in the kitchen, creative genius, all these things...they were mythologized by the industry, by the media, by the chefs who pursued it. And certainly I was one of them unintentionally, yeah.

And some people were aware of the stupidity of it all and other people warned, and I just didn't see it. I think moving forward some people have a responsibility, and I hope I'm one of them, to change the conversation. To say that the brigade system and the verbal abuse, the harassment, all the things that have become sort of synonymous with something that, if you read Kitchen Confidential, was oftentimes glamorized, right?

This rough-and-tumble crew of misfits really shouldn't be romanticized. We should find a more equitable way. I don't have the answer, but that's part of the process of why I think we should start talking about it. It's not going to be an easy road because how you cook in restaurants, at least independent, ambitious restaurants, it's all built on a military system. And that's not the only reason, but it's something that all of us collectively need to start to ask, "Did it actually even work well to begin with?"

KJ: That's so interesting. I didn't realize that about the military system.

DC: Yeah. [Auguste] Escoffier built it on the French military system, the brigade, and it's a top-down command and control. Not all kitchens, but the kitchens where I learned, it was like being in the military and it doesn't have to be that way.

KJ: You brought up Kitchen Confidential, and I did want to ask you about Tony Bourdain, who was your friend who we lost in 2018. And at the time, I think partly because we had lost Kate Spade at the same time, there was a lot of discourse around, "How can someone who's so successful be so unhappy?"

Do you think that people understand more now that mental health issues are separate from success? And where do we still need to go with that?

DC: Well, Kat, I don't think people are aware, and unfortunately suicides happen all the time and it doesn't have to happen with someone who is rich and famous and beloved. I mentioned this somewhere else, but the way I've phrased it to the people around me who've asked me about suicidal ideation and how can someone, whether it's me or someone else, be depressed and it's still like, you don't ostracize someone, but you almost put them in another bucket like, "Oh. That person's having problems."

The best way I can describe it to people is, could someone who is successful, loved, who has what seems like everything, the world in their hand, have asthma? Could they have some form of cancer? Could they have a tumor? No one would ever look down upon them for that. And so much of mental illness is a biological condition. A chemical imbalance in your brain.

Certainly there are cultural and environmental things that can trigger certain things, but regardless, it's an illness. Someone who's an alcoholic, you wouldn't say like, "Well, fuck you." We've learned.

You think about the past 25, 30 years. We've really learned how to think about someone who has an addiction problem. It's still a process that we're learning to talk about. And we're in the beginning stages, still, of destigmatizing mental illness and all of its facets.

I hope that this book and other books are just — it's not going to be the solution. I think the way to get there is to simply talk about it and not to make someone feel like something's wrong with them in a different way of being ill in any other way. So, I hope that made sense, but no. I don't think we're anywhere close to removing the stigma and the taboo of talking about mental illness.

KJ: I really appreciate your saying that. And I'm just going to insert here for any listeners. If anyone is having thoughts of suicide, that you can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at +1 800-273-8255. But thank you so much for that, Dave. That was really good to hear.

I do want to, awkward segue, but I do want to talk to you about some more fun stuff before you go. Because I know you're a really kind of omnivorous person in general. You have the podcast, you do TV, and now you're a published author. Can you share with us anything you're really excited about reading or listening to lately?

DC: I just reread Lisa Donovan's book. She's a chef in Nashville. She wrote a memoir called Our Lady of Perpetual Hunger. And I just encourage people to check that out. It's an unbelievably good memoir and as talented as she is as a chef, don't even think of her as a chef. She's an unbelievable writer.

I had Alex Ross — he's the music critic for the New Yorker — on my podcast about a year ago. We talked about his upcoming book that he has now just released, Wagnerism, Art and Politics in the Shadow of Music, and so I just started that.

So, there are a lot of books to read or to listen to. I don't even know how you guys listen to so much. There's so much content out there. And Audible has literally, what book does it not have? I don't know where to begin. I find that now that I drive in LA a lot, I don't listen to music anymore. I listen to Audible because it's part of my Amazon account, and it's just an easy way to listen to something without getting into the music.

I find it to be way more productive for me, because I can weirdly drive and listen to my favorite thinkers of the world. Right now I'm excited. I want to get Alex's book on Audible and then, I don't know, what other books should I be listening, reading? I want to finish listening to Cathy Park Hong's Minor Feelings. I think that's becoming a seminal book for Asian Americans and I refuse to read or listen to any Trump book. Too many. I mean, come on.

KJ: You know what? I have some recommendations for you, actually. Two things I've been listening to that I think you would like. Luster by Raven Leilani is amazing. That was kind of the book of the summer that everybody has been listening to and it's phenomenal.

DC: Luster?

KJ: It's literary fiction about a young Black woman who kind of gets into this affair with this couple that lives in New Jersey. So it starts off very sexy, but then it kind of detours and becomes about something else entirely. It's like when you read somebody new and you're like, "She's got it. She's got that talent. She's it." So, I love that one.

I was also thinking you actually might like the new translation of Beowulf because I read a Times article where you said you listen to Beethoven's Ninth a lot. So you like classics, and you're just this kind of fusion-y guy. And I feel like this is a really modern new translation of Beowulf. It's a little bit like what Hamilton did.

DC: Okay.

KJ: The first word is "bro." But it's by a serious scholar [Maria Dahvana Headley] and the narrator, JD Jackson — his voice is like butter. It's so good. I was never forced to read Beowulf.

DC: By the way, Beowulf, what an amazing book that they forced kids to read in like elementary school or seventh grade.

KJ: It's hardcore.

DC: I can't wait to listen to this. “Bro” is the first word uttered? All right. I'm listening to this.

KJ: It's fantastic, so I'm excited that I got to recommend something to you. I would be remiss if I didn't tell you if I've had some of the best times of my life at your restaurants, like my bachelorette party at Ssäm Bar.

DC: Well, thank you for celebrating that with us at Ssäm Bar. I'm so happy to do that.

KJ: I loved it. But what do you think about the state of the restaurant industry right now, and how are you feeling about things?

DC: I wish I could be a more optimistic. It’s not a very good place right now. A lot of people are hurting and while it's terrible for restaurants, it's more terrible for the people who work in the restaurants. And I'm hopeful that we can make some positive change.

I'm hopeful that this is a reset and we can come up with some really ingenious solutions to impossible problems. Without talking about it forever and really depressing people, I don't know if the government is going to do what they need to do.

In the interim, before we find some solution, and there's just no way we could sort of distill this topic into even an hour conversation. So, apologies, but I think the one thing that you can do is to support the one, two, or three restaurants that you can't live without, and really support them as much as humanly possible. Because it doesn't have to be a restaurant, it could be any small business.

This is an incredibly tough time. And disposable income is not sort of as easy as it used to be for so many people. So, I know that it's a difficult ask for so many people, but if you can support restaurants, I wouldn't do a lot of them. I would just ask which ones are the cultural institutions. They don't have to make great, great food, but which ones are so important to you that you can't imagine living without them? And I would try to prop them up and spread the word as much as possible.

KJ: That's great advice from David Chang, whose memoir Eat a Peach is available now on Audible.

DC: Thank you so much everybody. To the entire Audible community, thank you so much.

KJ: Thank you so much.