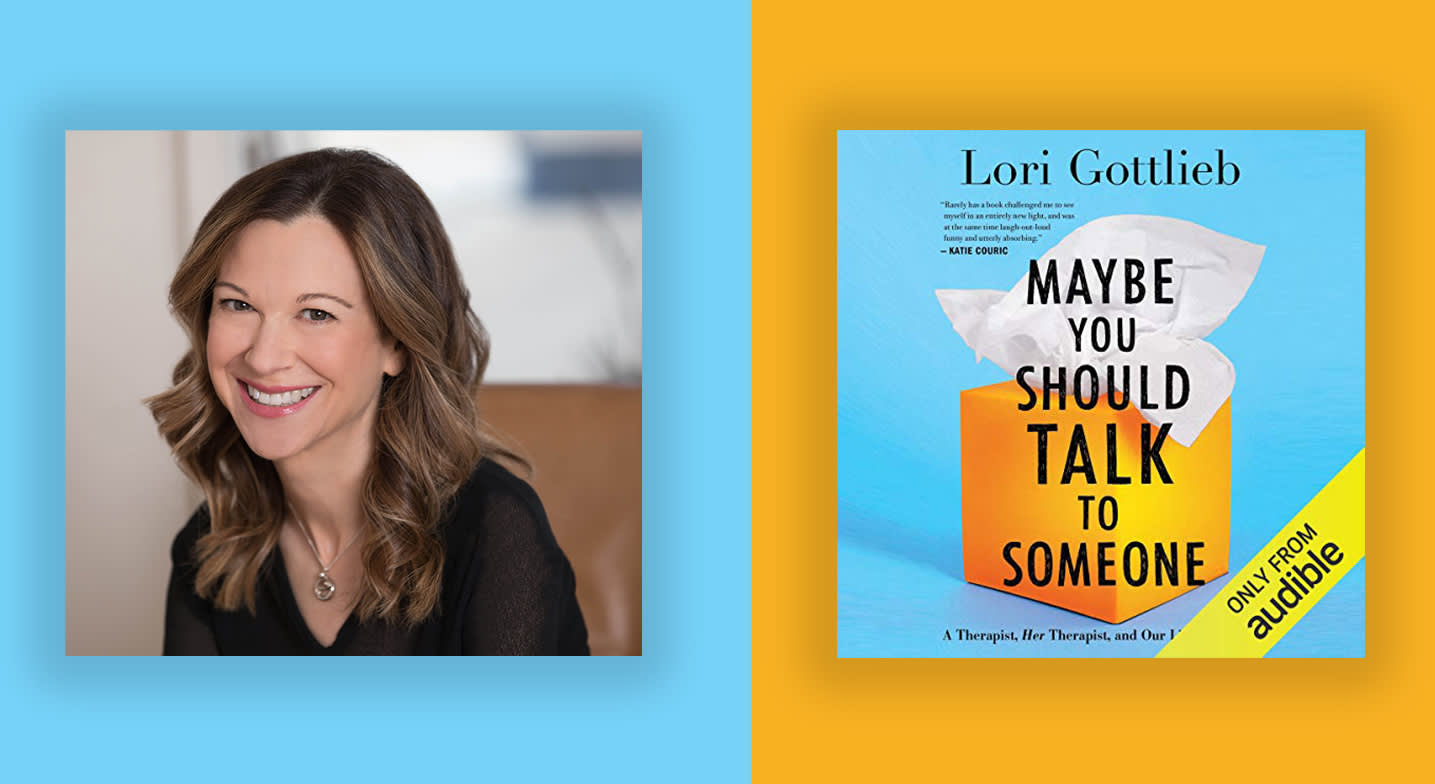

It's rare for a memoir to draw you in with engaging storytelling peppered with lightbulb moments, only to have you find out along the way that it's really a self-help book in oh-so-clever disguise. Lori Gottlieb's Maybe You Should Talk To Someone does just that. The best-selling author and "Dear Therapist" columnist from The Atlantic brings us all into the therapy room, strategically sharing the journeys of not just a handful of her clients but her own therapy journey as well.

Listen in as Lori talks with editor Abby West about why she chose the patients and stories she did, what the overarching messages of the book are, and how she knew they would resonate for us all.

Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

Abby West: Hi listeners, this is your Audible editor, Abby West, and I'm so excited to talk with Lori Gottlieb, author of Maybe You Should Talk To Someone. I've been talking about this book nonstop to friends for months. Lori is a psychotherapist and a writer whose controversial best-selling book, Marry Him: The Case For Settling For Mr. Good Enough, polarized readers nearly a decade ago. Her new book, a memoir, expertly weaves her own journey of getting therapy at a pivotal point in her life with stories from four vastly different and intriguing patients. With a number of resonant moments, it is a wonderfully entertaining and therapeutic listen. Lori, welcome.

Lori Gottlieb: Thank you. Thank you for having me.

AW: I'm very excited to have you here. Now, the subtitle of your book really says so much about the appeal. It's "A Therapist, Her Therapist, And Our Lives Revealed." I know in large part it's about your therapy journey, which was kicked off by a surprise breakup with your long-term boyfriend. You obviously knew there was something in this journey that would resonate, but were you surprised by just how interested the public at large is in the idea that our therapists have therapists?

LG: I think that people know that our therapists are real people, but I think sometimes they don't think about that. What's interesting about that is, that the fact that we are just regular people going through the world is our greatest tool. I always like to say that I'm a card-carrying member of the human race, and that my humanity is, despite all of my training, I think the thing that helps people the most in the therapy room. So, I really wanted to bring people back in and show them what that looked like.

AW: That's great, because I think it is that idea that in the middle of this really personally crushing moment you had to go and be that rock, that person for others in the therapy room. I will speak from personal experience that, when I go to therapy, I'm not always considering my therapist personal life going in there. It is a very selfish moment for many of us, and to see how our therapists, how you particularly, navigate that is so wildly interesting for us.

LG: Right. Nor should you be thinking about what your therapist is going through when you're in the therapy room. The session is yours, and it's very important that, even though I was going through what I was going through, I never brought it into the therapy room with my patients. That was why I went to see a therapist, because I needed my own place to really process and understand what was happening in my life at that time. Therapists should never bring their own issues into the therapy room. That is not what therapy is about.

AW: No. It was also fascinating to hear how therapists meet together in... I forgot what you call the dissection.

LG: Consultation groups.

AW: Consultation groups to help each other work through different patient issues, and help to find the best resolutions or the best paths for different patients. Pointing you guys in direction of having your own therapist. It's just a really good insight for so many of us to understand how you're doing it.

LG: I think a lot of people imagine that therapists sit alone in a room with our patients, and it seems like that's all we do. But there's a very rich life that we live. Part of that is that we get together with our colleagues in these consultation groups and we discuss our cases and get feedback on the work that we're doing, so that it's not just us alone in a room, but it's also us talking about what can we do better or where are we stuck or what did we miss? Even the things that other people get in other professions, which is "Good job! That thing that you did there, that was really hard and that was a really good intervention." I think in other professions, people either see a work product, or they're working on teams, or somehow, they're getting some feedback on what they're doing. We need that too, to be the best therapist that we can be.

AW: That's fair. You don't actually get the validation that many people get them in the office environment, right?

LG: Yes.

"...story is the way that we make sense of our world and the way we make sense of ourselves."

AW: I have to tell you that I became so invested in each of the patients that you featured. We meet them at these very specific moments of either crisis or approaching crisis. I also love the insight that we work in stages of being able to address issues. Sometimes people show up and they're not actually ready yet, but they are on the verge of being ready and this helps them get there. We meet these four patients -- a young woman who's a newlywed diagnosed with terminal cancer, an older woman who's full of regrets and finds her life to be meaningless, a self-absorbed Hollywood producer, and another young woman who's in a cycle of alcoholism and damaging relationships. Then we go on their journey the same as we go on yours, in such an engaging way. How did you go about choosing the patients that you did?

LG: Such a great question. I really wanted to write about four very different people who seem very different on the surface. But I think that we can see aspects of ourselves in all of them, even in my story. I think that one of the messages of the book is that we're more the same than we are different. You can see that with, as you were saying, there's this young woman who is always hooking up with the wrong guys, including one in the waiting room. And she thinks that's a step up because she says, well, at least he's in therapy. But of course, it's not. Then you contrast that with the woman who's about to turn 70 and her adult children won't talk to her. She's had some marriages that didn't work out. She's very isolated and unfulfilled. She says, if things don't change in a year, I don't want to live anymore.

So you have this person who has this vast vista ahead of her, the young woman who can make better choices. Then you have this woman who has already made such significant mistakes in her life, and what do you do with regret and what you can't change? And is it ever too late to change? That's a question for her. Then you have this woman who is newly married and seems to have everything going well in her life. She's actually a really happy person, but she comes back from her honeymoon and finds out she has breast cancer and how does she deal with that? Then you have this person who is a very successful Hollywood producer, who keeps everyone away from him. He can't let anybody in. He's very abrasive and off putting. He says to me, he's coming to me because I'm a nobody.

Therefore, he won't run into any of his high-powered colleagues when he comes. But when you see the trauma and the tragedy underneath the way that he's protecting himself, I think he becomes the person that people tend to love most in the book. In real life, I developed a real deep affection for him. So, I chose people who seem so different in terms of their personalities and their ages and what they're coming in for. But I think that what connects all of them, and me, and I hope the reader, is our shared humanity and the pieces of each person that we can all relate to.

AW: I think that definitely comes through. I was stunned by my turnaround on him, from so severely disliking him in the beginning, to crying over him towards the end. That journey is very important to see, because it does resonate. The details may differ, but a lot of the themes are the same.

"We want to be happy as a byproduct of living our lives a certain way, not searching for happiness as the primary goal."

LG: Yes, absolutely. I really think that part of why I wanted to bring people into the therapy room instead of writing about "here's how you can learn what these people have learned," I wanted them to see it through story. Because I think that the stories are so powerful and I think that story is the way that we make sense of our world and the way we make sense of ourselves. I think the book is all of these stories that seem to be about other people. But I think the stories are really about the reader.

AW: I love that. I want to come back to your history with writing and how that really played into this, but what was the feedback from your patients? I think a lot of us really want to know, how do you go about getting people to say, okay, do this, even with the names changed and all of that? And what was their feedback in seeing themselves in this way?

LG: Well, I didn't write about anybody that I was currently seeing, because I didn't feel that I could be writing about them and doing the work in the room with them at the same time and keeping those separate. That was really important to me. Of course, I got permission. But I think people want to use their experience to help other people, in the same way that that's what I'm trying to do in the book. I'm certainly not the first to do this. Irvin Yalom did this, famously for Love's Executioner. There are other clinicians, [such as] Atul Gawande, who often writes about his patients. I'm not the first clinician to write about what happens with my patients. I think that we all go through the same process with our patients in terms of comfort level and privacy and permission.

AW: Have you heard back from them about how they are portrayed in the book?

LG: One of the things that I think was really important to all of them was that, I not talk about them in the present, because I got their permission to talk about them in the book, but I don't talk about them in the present.

AW: Oh, okay. I see. Understood. That makes sense. Let's talk a little bit about Wendell, your therapist. It is such an intimate relationship, as a therapist and patient relationship goes. Including the part where you wrestle with whether or not you're subconsciously attracted to him. Which, again, is kind of universal for so many of us, that I cringe for you ever to ever having to make him aware of all your inner thoughts, but did you find the fact that you'd already shared so much with him made it easier to bring all of that to light in the book?

LG: Yes. There's nothing in the book that he didn't already know. I think that what's interesting about therapy is you end up talking about things that seem really, maybe uncomfortable, out in the world, but they become so comfortable in the context of that relationship. There's something intimate, emotionally intimate, about the therapy relationship, where so many people will say, I've never told anybody this before. It's actually different for men and women. Men will say, I've never told anybody this before. Then they tell you something that doesn't seem on the surface so private. But I think because men tend to be much less vulnerable with each other, that they really, really don't talk about these things. Women will come in and say, I've never told anybody this before. Then she'll say something like, except for my mother, my sister, and my best friend.

Then what they say tends to be, you can understand why it was more private. But I think in general, I do hear things that people are not telling people out in the world. Yet what we find is that, what people are telling other people tends to be the Facebook version or the Instagram version of their lives. They're not really talking about the things that we need to be talking about, because what happens is so many people start to feel very isolated in their circumstances. Because they don't know that other people are going through something so similar to what they're going through.

AW: That's absolutely the case. I think that was one of the many takeaways. I had a lot of nuggets of a-ha moments as they were, insights that really resonated. The patient-therapy relationship, the parent-child relationships, and just the intentionality that is required so much in life. You've mentioned the theme that we're more alike than different, but if you had to add a few other takeaways that you want listeners to have from the book, what would they be?

LG: I think a couple of them are first that we grow in connection with others. That there tends to be, I think particularly in American culture, this idea of independence and stiff upper lip. I don't need other people. I can do everything myself. But we do need other people and we have a lack of connection, nowadays, with everybody seemingly connected via technology, but not really sitting face to face together without their phones on the table, without interruptions, and things binging and pinging and vibrating and whatever they're doing. I think just unmediated by screens. That's even why I don't like to do Skype therapy, because a colleague called Skype therapy, it's like doing therapy with a condom on. It's not the same as a physical experience of the energy in the room hearing someone breathe.

We don't get that in our personal lives and our social lives either so much. We'll like something on Facebook, but we won't go and have coffee with that person. I think [the fact] that we grow in connection with others is what you see in the book, with me growing in connection with my therapist and my patients growing in connection with me. But it goes both ways. That I'm growing in connection with my patients, and I'm sure my therapist in some way grew in connection with me. I think that that's something that I wanted to show. How that works and why it's so important. That you need another person there to hold up a mirror to you and show you something about yourself that you're not already seeing.

I think the other thing is that, one thing I've noticed as a therapist is how unkind we are to ourselves. You can see that with all of my patients and also with me, that we tend to be so self-critical. We tend to be so hard on ourselves and we don't have a lot of compassion for ourselves. If you listen to the voice in your head, often it's so judgmental, and it's not that we shouldn't hold ourselves responsible. One of the main tasks of therapy, in fact, is to help people to take responsibility for their lives and not blame other people for their circumstances. But at the same time, you can take responsibility for yourself and not self-flagellate. I actually had a patient write down all of her thoughts during the week, the way she talked to herself. She was embarrassed because when she came back she said, oh my God, I can't even read this out loud. It's so horrible. She said, "If I said this to a friend, I wouldn't have any friends."

AW: It's very familiar. I'm cringing because it's so familiar and I know how I personally do it. That's, again, one of the reasons I love the book so much. It's moments just like where you mentioned that you wanted Wendell to like you. I remember feeling very embarrassed that I had wanted one of my old therapists to like me. I was just very invested in whether he liked me as a person.

LG: I do everything as a patient with my own therapist that my patients do with me. So, I did want Wendell to like me. When I would leave, there was always this woman, if she would come early for her appointment, I would pass her in the waiting room. She was the next appointment when I was leaving my therapist. She seemed so nice and put together, and I'd come out sort of a wreck in the beginning when I started with this crisis. And I always thought, oh, I'll bet he dreads my sessions or he must look forward to her sessions so much more than he looks forward to mine. I even Googled him one night, when he tells me that I need to stop Googling the boyfriend.

Right in the aftermath of the breakup, I would Google [the boyfriend] and I would see things that he posted. I would make up stories in my head, like, oh, I didn't matter at all to him because he's going to restaurants and taking pictures of salads in restaurants, and nobody in the throes of heartbreak does that. [Wendell] said, you need to stop. You need to stop Google-stalking the boyfriend. He said, you need to do something different when you have that impulse. I was about to type the boyfriend's name into a search engine and I stopped myself. But then I thought, oh, I've never Googled my therapist. I wonder where he went to school or what his background is. I went down the rabbit hole of Google-stalking my therapist one night. It was interesting because I found out that his father had died at a relatively young age of a heart attack, even though he had been a marathon runner. It was this sudden heart attack.

I had been talking in my own therapy about my very close relationship with my own father, who was ill and almost 80, and I was saying how grateful I was to have this time with him. That we were going to get to say goodbye in the way that we wanted. I had no idea that my therapist had had this other experience. I started editing myself in the therapy room because I didn't want to cause him pain. I finally confessed to him that I had Googled him and found this information. All the air returned to the room and we were able to talk about my father differently because I had told him the truth of what I had done. But I wasn't that different from my patients because I know that they Google me. They'll slip up inevitably, with something like, "Well, youknow what it's like to raise a boy who's in middle school." Even though I've never said anything about being a parent or having a son or how old he is.

AW: Yes. I guess it's a rite of passage, so you don't get too unnerved by it? It's just the way it is?

LG: Well, I think that it's very hard nowadays with the internet to not be able to find something about your therapist online if you dig deep enough. But I also think, I would caution people and say, well, why do you want to know? How is this information going to serve you?

AW: This is such a deeply personal story and it feels so uniquely your story to tell. Were you tempted at all to narrate it yourself?

LG: No. I think for a few reasons. Everybody asks me that question, since it is so personal, why didn't you narrate it yourself? First of all, I wanted it to be good [Laughter] and I'm not an actor, but I also think that I wanted somebody who wasn't that close to it to be able to bring the words that I had written to life in a different way. I'm so proud of how it came out. I think that the narration is fantastic on it, and I'm really glad that the person who did it was able to bring my words to life in exactly the way that I had wanted.

AW: Brittany Pressley did an amazing job. The idea that someone has embodied your work in such a way and brings it to life, particularly with memoirs, I find it very interesting to talk to authors about. Were you involved at all in choosing her?

LG: Yes. I specifically chose her in fact. I looked at various people who were possibilities and who were available and who had done similar types of material, and they were all fantastic. But I think I was looking for something. It's kind of like you know it when you see it. You know it when you hear it, in this case. There was something about the books that she had narrated and the way that she had captured them, that immediately I said, that's the person. Thank goodness she was able. She was so busy because she's so good. She had all these other commitments, but she was able to make this happen. I think she told me that she really loved the material and that's why she tried to make it happen.

AW: That's great, because it did feel like she connected with it. I think it's in large part, you've been writing for years. It's not like you're a therapist who only did academic work. You'd been in TV development, correct?

LG: Yes, I'd worked at NBC. I was working on a show called ER, which got me to medical school, which I eventually got me to journalism. I wrote about in a very accessible way for major publications, not for the academic market, but for the New York Times, The Atlantic, and women's magazines. I always wrote about psychology and culture. Even now I write the Dear Therapist column for The Atlantic every Monday. I do both, but I think they're very related in the sense of all of the things that I did. Even working in television. They all had to do with story and the human condition. I think I went from telling fictional stories in television, to real life stories in medical school, to helping people tell their stories as a journalist. Then I think as a therapist helping people to change their stories.

AW: I think that one of the underlying lessons and takeaways there, in hearing about your journey through your career and finding the next right thing for you. Then also figuring out that writing the happiness book wasn't necessarily what you wanted to do, that this was the book you wanted to write and taking that leap. That also was a big lesson in intentionality, I guess, in your life. Also seeing signs.

LG: I wasn't supposed to write this book, and I talk about this in the book. Originally, I had written a piece for The Atlantic called "How To Land Your Kid In Therapy: Why Our Obsession With Our Kids' Happiness Might Be Dooming Them To Unhappy Adulthoods." That was the book that publishers wanted me to write, but I didn't want to write that book. I was a new therapist at the time, and I felt like I wanted to write about something that was happening with the adults. I felt like, as The New Yorker later said, another book about over parenting, which would be cruel.

There are so many great books out there about it. I didn't feel like it would really have meaning. I was really at a place in my life when, as you can see in my journey in this book, that even though it starts off with the boyfriend incident, it's really a book about me finding meaning at midlife and reevaluating my life and really not wasting time, as we see with my work with Julia. She's going through cancer. She makes me very aware of my mortality and all of our mortality, and that we really need to live every day. What are we waiting for? That we really need to live our days the way we want to live, because none of us knows how much time we have. I think that having that awareness was important in the sense that, I didn't want to write the kid book, the parenting book. And I was supposed to then write a book about what they called happiness, but that wasn't really capturing anything that I was seeing in the therapy room. Because happiness is beside the point.

By that I mean we want to be happy, but we want to be happy as a byproduct of living our lives a certain way, not searching for happiness as the primary goal. It comes from connection and meaning and purpose and all of the other things in our lives and relationships. By relationships, I mean relationship to self and also relationship to others. Those are the things that I wanted people to see. I was trying to write this book that I didn't have my heart in, and I would sit down every day, and people would say, how's the book going? I felt so much shame around not being able to write this book after having turned down the other book that everyone thought I was crazy for turning down. It was almost like the gambler who gets dressed every day to go to work and kisses her partner goodbye and then goes to the casino instead of the office.

When people would say, how's the happiness book going? I'd be like, well, it's going. But I wasn't able to write it. Eventually, I called it the "miserable, depression-inducing, happiness book." The irony that the happiness book was making me miserable, but I couldn't even talk to my own therapist about it. I had so much shame around the fact that I couldn't write it, and I felt really trapped by my circumstances. Because my agent was saying, if you don't write this, after all of these other mistakes you've made, you will never write another book again. My therapist said, you remind me of this cartoon of a prisoner shaking the bars, desperately trying to get out, but on the right and the left, the bars are open. I couldn't see that I had choices.

I couldn't see that it was open on the right or the left. I think that so many people feel trapped like that. I actually brought that. I went from his office to my office, and for the next five hours, I repeated that to various people in the therapy office. Because no matter our circumstances, I think so many times we feel like we don't have choices where we do.

AW: Right. You're helping to reveal paths for people or have them look at it and find their own paths and that's critically helpful.

LG: Yes, I think it's important for people to look at the story that they come in with, and look at it from a different angle. So often people will come in with a story of, usually it's that they want to change someone else in their life. But then when they start to realize that they might have a role in this, or that they have choices in how they respond to these circumstances, it's still hard to change. I think it's hard for us to look that the bars are open, because with change we have to take responsibility for our lives. I think sometimes it's hard to do that. It's hard to take responsibility, because we feel like we might make the wrong choices, or if things go badly, we only have ourselves to blame. Also change involves loss, that sometimes we cling to the familiar, even if the familiar is unpleasant or downright miserable. Because we don't want to go off into the new thing, which is rife with uncertainty. Humans are very averse to uncertainty, and so we cling to this thing that's very familiar to us.

It's why it's so hard for us to make the changes that we know we need to make. Even though we might know exactly what we need to do to change, sometimes it takes us a long time to make those changes. It doesn't work like Nike, just do it.

There's a lot of emotional preparation that happens before you just do it. I like to say that, in the therapy room, change happens usually gradually and then suddenly. So, when you get to that just do it moment, there's been a lot of seeding that's happened before that. There's been a lot of preparation that maybe you weren't even aware of, that allows you to come to that moment of just doing it.

AW: When you hit that moment, it's like, okay, now everything should magically fix itself because I've got the answer. It should move forward.

LG: Right. We like to say that insight is the booby prize of therapy. That you can have all the insight in the world. People think you're going to therapy to learn all these things, to gain insight. It's partly what you do, but mostly we want you to use that insight. You can have all the insight in the world, but if you don't make changes out in the world, the insight is useless. So, someone says, now I understand why I keep getting in those arguments in my marriage. But then they go home and they do exactly the same thing in their marriage, and they're not making those changes, then nothing is going to change and they're actually wasting their time in therapy. We want to guide people, not just to create more awareness for them around what they're doing and what they can be doing that will help them, but then also making those changes.

AW: Well, I think this book is a real good help for people to find that path and to see the options that they have available to them. Because as I mentioned, it's entertaining and therapeutic at the same time. It's like, what is that phrase? A spoonful of sugar makes the medicine go down a little bit. It's not meant to be a harsh lesson. It is just a lot of interesting engaging stories that really leave you with a wonderful takeaway. I hope other people will see that too.

LG: It's easier I think to see ourselves through somebody else's story. So many people have read the book so far, say, oh, I saw myself doing what so and so does in the book. I think that that makes it clearer. Sometimes we need to see somebody else make the mistake that we're making, before we realize that, oh, I do that too. I think that that's how people change, is to realize that there's something that they're doing that's not working that they hadn't seen before.

AW: Right. Lori, thank you so much for hopping on the phone with us to talk about, Maybe You Should Talk To Someone, which is, again, one of my favorite books this year already, and it's available on Audible.com

LG: It's my pleasure. Thank you so much for the conversation.