Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

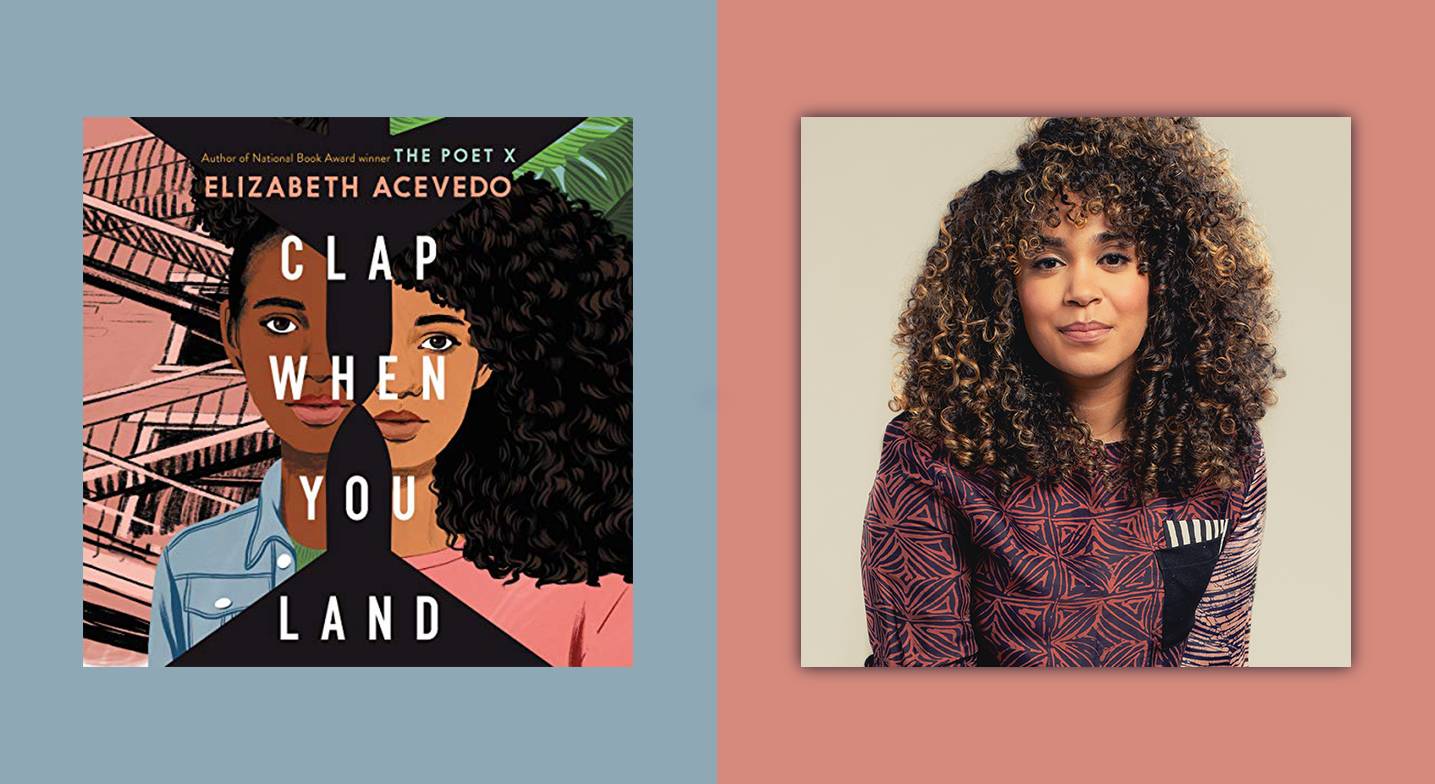

Edwin de la Cruz: Hi everyone, I'm Edwin, an Audible editor. We're here to chat about Clap When You Land. This is the latest novel by Elizabeth Acevedo. She's the author of The Poet X and With the Fire on High. The Poet X is a New York Times bestseller, National Book Award winner, and Carnegie Medal winner.

Clap When You Land is an incredible addition to this author's growing body of YA literature. The story is about two girls, Yahaira, a New York teenager and chess prodigy, and Camino, an aspiring doctor living in the Dominican Republic with her aunt, a curandera, or faith healer. The two sister's worlds collide in the aftermath of a plane crash that was traveling from New York to the DR, when both girls find out that their father who died in the crash was keeping each other a secret.

Welcome Elizabeth, how are you?

Elizabeth Acevedo: I'm well, I'm well. Thank you so much for having me.

EdlC: Elizabeth, I have a personal story regarding the tragedy of flight AA 5[8]7, which crashed on its way to Santo Domingo. And that made your novel resonant for me from the beginning. What was it about this event that inspired you to tell the story of Camino and Yahaira?

EA: I remember being pretty young when flight AA 587 crashed in Queens. I was probably 13 or 14, and this was two months after the attacks on the World Trade Center. You know, born and bred in New York City, it just felt like an incredible amount of loss, both as a New Yorker and as a Dominican, in all of two months.

It really rocked my community. We had a neighbor who was on that flight. There were two neighborhood friends that I had, their father was on that flight. I remember walking through 181st and Dyckman [Street]—I would go with my mom on shopping trips—and seeing the vigils outside of people's apartment complexes. We could call it a small number, 260 people, but at least for me, and possibly because I was a child, that number felt immense.

It felt like there was so much we didn't know about those people and so much that was swept under the rug once it was determined it wasn't terrorism. And I felt like it deserved more than it received, at least at the time. More attention, more care, but also generosity of... what was the work of supplying dignity for the people who were lost on that flight? And can we keep doing that 20 years later? Do we still remember?

EdlC: That makes sense. I know that the crash happened on the aftermath of 9/11 too, so I'm sure that contributed to everyone's anxieties. And the fact that it was overlooked, because by that time we were still having stories about 9/11, and… well you know what happened afterwards.

One of the great feats of this novel is that Papi's character looms large throughout the story without ever actually being introduced. He lives in the memories of the characters, where we learn that he was a good father to both Camino and Yahaira. But he wasn't a particularly good husband to either of their mothers.

What was it like to write a central character who isn't actually alive for the story?

EA: It was odd. I kind of set myself up for this project very early on because I knew I wanted to start the book on the same day that he dies. Usually you want to establish a certain sense of the world, the normal world, and then there's something that happens that changes it and that the character has to respond to.

I didn't really establish any normalcy. Normalcy is established through nostalgia, it's established through their memories, but you are thrust into the rupture of the story from the very beginning. And it all relied on that father character—on the ghost literally haunting the novel—feeling like a character.

He is not there, but how do I establish his presence throughout the book? How do I get him saying the things that he says to come over and over? There'll be moments that the girls catch themselves in the mirror or a window and they see his face in their face. And so how do we talk about loss and the space that a person's loss can take up?

That for me was one of the projects of the book: Can I make this work even though this character will never appear but is central to every other character's ability to move forward?

EdlC: Right. That's probably one of the things that resonated with me the most, the fact that their story, that they didn't know about each other—that happened to me. My father had a parallel family here in the States while we were living in Salcedo in Dominican Republic.

And my follow-up question to that is something that has always been on my mind about Dominican men. But as a Dominican myself, this is something that I struggle to comprehend, that some Dominican men have parallel families. And I know it's true for my family. Was there a cultural reasoning behind that setup for you?

EA: You know, this book tackles a lot of different cultural elements that I've been wondering about for a while. I talk about sex tourism, particularly in Sosua, that's a big thing that happens there. I've done work with a young women's project, Mariposa [DR] Foundation over there and seeing the way that it affects.

So I knew going in that I was going to take on a lot of different Dominican pillars in order to try to understand what's happening. And one of them for me was: What are the stories that we hear about men who have different families, different wives, and multiple children? And the ways that we make space for those men in our lives?

I think that that's a big part of it too. It's not just that these men have separate lives. But that the society at large makes that permissible in a way that I've always found fascinating.

And so the book is thinking through: What does it mean for this to be permissible? What does it mean for this to be really normal in a lot of ways for the older generation who knows about what's going on but doesn't necessarily step in? And what is it that these two young women are trying to voice? Which is like, "You did us such a disservice. And it's not that either one of us wishes you weren't here, but we just wish you could have been different in how you made this come to be."

And so for me I would say I wasn't looking for absolutely any answers when I introduced the father character as much as I was just intensely wondering what could make someone who everyone else might think is a perfectly good man and a great leader in his community, and takes care of his people, also have these parts of him that are difficult to reconcile, right? And I think in an effort to not demonize Dominican men, or demonize Latino men, I have to make it human. But I'm also wrestling with the fact that this is messed up, and it's messed up that we'd normalized this.

And so it was a push and pull on: What does it mean for me to have to sit with this character that I have very strong opinions about, and try to still create a nuanced story?

EdlC: I completely agree. And in my case, even when I listen to your novel I had already had this... My dad passed away four years ago, and I already had forgiven him. And I think that's part of your writing in this novel, that it's also about forgiveness. I found that very healing in listening to this novel. Clap When You Land is told in verse, and I must admit that I initially proceeded with caution because I don't usually read or listen to poetry.

EA: Fair. I get that often.

EdlC: But I was quickly captivated with how the verse traps you into the story. Can you share with us a little bit about your writing process in verse?

EA: Yeah. I wasn't sure that this was a novel that would be able to be contained in verse. Usually with something that's more adventurous, where you have multiple settings and a lot of characters, I tend to think that prose does better because it can contain all of that information, [whereas] verses come at you very quickly, so trying to establish a complicated family structure or dialog is hard.

But I also felt like I wanted the music of New York and the music of the Dominican Republic to come through. I wanted to have rhythm be a really big part of the story. I wanted to sit with these characters. And I think poetry automatically lets you know like, "This is going to be a contemplative endeavor. I'm going to need you to stop and sit with the metaphor, I'm going to need you to pay attention to imagery. You're probably going to have to reread a passage."

I wanted folks to take that time out, you know? You always get accused that a verse novel—or not accused, but one of the things that is hailed about a verse novel is that they're quick reads. But I also think they make you stop a lot.

And so here is a story that, when you hear the pitch, it's almost like... It sounds completely made up, right? There's a plane crash, there's a secret family, there's all of these things happening. I'm like, "But all of that was true, all of that was based on my research." And so there's a strangeness to this story, and I think there is a strangeness to verse, trying to hold that kind of story.

It just made sense for me to push what was possible in the expectation around this narrative. But also to echo some of the things I thought were there. All of the praying, all of the music, all of the ways in which the girls move and walk and are listening to their surroundings. I wanted the ability to bring all of that rushing through. And I think verse lets you jostle and play with language in a way that is disruptive. And I wanted this novel to be a little bit disruptive.

EdlC: And just speaking of verse, I know that while listening to it, it was almost like a song, because [the] audio overall just fits this narrative so beautifully well. And at the chapters between the voices of Yahaira in the US and Camino in the Dominican Republic, they oscillate between each other, they give the listener a simultaneous, parallel view of how each sister lives their lives.

Ultimately the novel ends fittingly with their voices in unison. Was this a conscious decision? And when in the writing process did you begin to think of the audio version of Clap When You Land?

EA: The first version of Clap When You Land only had one sister. It was only Yahaira's story. And I was talking with a writer named Ibi Zoboi, who's a Haitian writer—she wrote a book called American Street and Pride, which I actually did the narration for. As I'm telling her about this idea, she's like, "You got to get the second sister. We have to hear the other voice."

And when I began thinking of the sibling, when I began thinking of Camino, she did come to me very much verbally. I heard her first. I heard that poem. The book opens up with a meditation on mud, and I kind of... That snippet of: This is her voice and she's going to sound very different than Yahaira.

In general my writing tends to be very auditory. What are phrases or words or things that catch my attention? It's why there's always, in all of my books, going to be one passage that's just looking at the definition of a word. In this case there's the mud meditation, and there's also one on dar a luz [to give birth]. What does it mean "to give to light"?

And so for me I'm always thinking about, "Oh, how do these words sound? And what do we think they mean?" And then when we say them in Spanish versus English there's a strangeness that happens. Like, "give to light" feels so weird but in Spanish I'm like, "Es normal. This is normal."

For me, it's a game. I already heard it when I was writing it. I read all my books out loud while I'm editing. So I have in my body a sense of exactly what I need it to sound like. And it's, "Can I execute that?"

Once that second voice came in I was like, "Okay, I can hear it now. I can hear the narrative in their voices and how there's different—" And I was recording With the Fire on High, my second novel. So I was in the studio and I'm talking it over with the audiobook director, and I'm like, "The next book is going to have these two characters. And I'm so excited and there's these voices." And she looked at me and she was like, "You know, you probably won't be able to perform both. That could be really confusing."

When she said that, I was still writing. I began thinking of, "Oh, this is going to be a voice that literally belongs to a different body. Someone else is going to have to perform this. And so I have to be conscious as I'm writing that my style, the ways that I'm approaching this, [needs to] be something that another poet or another writer can lean into."

I would say about a year and a half ago I became aware of: Okay, I'm writing the story but I'm also writing thinking about the audiobook at that point. And which one of the two sisters I would want to perform and which one felt more exciting. And that pushed my editing, because I'm like, "If I really just want to perform Camino it's probably because there's something in Yahaira's story that doesn't feel as compelling in the language." So then I'm editing to make sure, "Wait, if I have to perform Yahaira I want to make sure she's just as good."

It felt like when people interview Lin-Manual Miranda and they talk about Hamilton, and he's like, "I gave all my favorite songs away." Right? His favorite songs were all the Aaron Burr songs.

So I was writing it knowing, "Dang, this is a bar and I might not be even the one to say it. But I know that I want to give this other person, whoever they might end up being, a lot of room to play with, a lot of ability to find nuance and pockets in the language that they could bring their own to." So I say it was a long time thinking about the book in its auditory version.

EdlC: I totally get it. You narrated your previous books and did a dual narration in this one. Do you enjoy the narration process?

EA: I do. I have a lot of fun. I come from a performance background. I did spoken-word poetry for a long time. I still do about 40 presentations a year, mostly keynotes, but I perform a poem at almost every presentation. And so a part of me enjoys the performance of it, literally getting into the studio and thinking through, "All right, the audiobook director has read this book however many times, she has her own ideas of what it needs to sound like. And I'm going to convince her my ideas are better."

For me, it's a game. I already heard it when I was writing it. I read all my books out loud while I'm editing. So I have in my body a sense of exactly what I need it to sound like. And it's, "Can I execute that?"

And then it's a fun moment of, you know, my director will come back and she'll say, "I think you need more here." And at first I used to get kind of offended, like, "No, I know exactly what it's supposed to sound like, I wrote it."

But I've learned the collaboration, the ability for me to realize, "Oh there are nuances, there's depth in the language that sometimes I don't even hear." She catches an opportunity like, "If you said it this way it would layer in wonder, or would layer in awe, or would be complicated." And so I have to then expand what my thinking of the text is.

So I find it to be a really fun collaborative process. It's hard. Like, some people I think imagine, "I’m going to go in and just say my own book. It's going to be a great day of work." It's like, four days, you repeat the same paragraph over and over. You hit that one word that you just can't say and want to edit. I edit as I'm going so it can be really frustrating to realize that we are at the last step and I want to change a character, I want to change a name, or I want to change an entire passage. And so having to think about, "Well this is what the book is and my performance is going to have to do what I'm trying to edit. My acting has to be enough."

It's a complicated process for me, but I couldn't imagine anyone else doing my own work. Even through this, and I got to help pick Melania-Luisa Marte, who's also a Dominican spoken-word artist, I was the one who sent out names. I did a lot of it, and even then it was like, "My precious." It's hard to let go. So I will step up to the plate anytime.

EdlC: That's good to hear because we love listening to you. So please continue. Going back to the theme of Dominican Republic for a second, when I visit relatives in the Dominican Republic... By the way, I'm from Salcedo, from Hermanas Mirabal. I have some cousins that—your words in describing Camino's house for instance—it brought back a lot of memories because some of these cousins that I have are not well economically. But you said something in the novel that really rang true, in that everything was in order. While they were not rich, the house was tidy. And that's true in my experience.

So this novel gives us a very honest account of Camino's life, which mirrors actually how a life is for many Dominicans on the island. Why was it important for us to know so much of Camino's class status and her struggle? Because while I was listening to it I somehow... I couldn't decide which sister I liked more. And in the first half I really gravitated towards Camino, but halfway through when they eventually meet and we know that Yahaira's coming, Camino starts having doubts about "Could she be a comparona (someone that’s conceited)?" and she has all these doubt about her. So could you tell us a little bit about that?

EA: Yeah. I wanted to be mindful, especially because Camino's character was coming into the story after I had already written it. And so I'm bringing in this other dynamic. I didn't want to write a stereotype. I think when folks are writing about other places or multiple countries it becomes a comparison between, you know, first-world and an island. And what do they have and what don't they have. I wanted to demonstrate the ways in which they both have, in some capacity, and they're both lacking in others.

And I wanted Camino's community to feel like a community. There are some awful people, there are some terrible things happening. But there's also Don Mateo next door who always gives her una bola (a ride). There's the neighborhood dog, there's the fruit lady who looks out for her and the ice cream person. There's her best friend who's Haitian descent and whose family has taken care of her.

It was important that in the first book where I am writing specifically about the Dominican Republic and about another place, that I really create it in such a way that it is rich. That if you're reading it and you read it generously [are] actually paying attention, you realize, "Oh, this is an island that has some things going on, and also some beautiful things going on. And it's more than the resorts but it's also more than the terribleness." The people make it a different place than the government or the organizational structures.

And so I needed to give a lot of detail because otherwise I was nervous that people wouldn't have enough information to actually have to wrestle with the fact that this is not going to be an easy place to hold, because no nation is. And I can't give you a cookie-cutter representation of palm trees and colorful houses and that's it.

It felt important to talk about Callejón (Camino’s neighborhood) as it is, but then also the malecón (jetty, waterfront promenade) being beautiful. You love this place, you just wish it could be better for people like you.

EdlC: I absolutely agree, and I also think that a lot of Dominicans don't necessarily want to leave. I think we love our island, but as you mentioned, the political issues, the corruption: that's enough to drive some people away. But at the same time, in going back to the title of the book, when we get on a plane and land in the Dominican Republic, everyone claps.

EA: Of course. And it's exactly that. In a book for children, how do you capture that you can hold multiple feelings about a place at once, right? And so I had to mirror what Yahaira felt about New York and about her home, which was, "I really love this place but also there are things here I'm not happy with." And Yahaira has that very clearly on her side.

One Camino's end, her issues are a little bit more escalated. We are talking about what is relative poverty, what is relative power, what is relative privilege versus absolute. There are things that Camino clearly lacks that are just at the most basic, like, "If we don't get a check I don't know how we're going to eat." That's very different than some of the issues that Yahaira deals with, but I didn't want to give one more importance. I just wanted to hold them all together and be like, "These are the many ways that Dominicans can exist, and it can be with multiple issues and multiple methods of healing, and a lot of different ways of talking about themselves and who they are."

I love that you said that you flip-flopped on which sister you liked best. I flip-flopped on which sister I liked best as well. And I think they both hold a different tenderness, a different like, "Ay, pobrecita! (oh poor little girl!) Ay, bendición (oh bless!)" right? All the time I'd be writing I'd be like, "Ay, bandito! (Caribbean Spanish-speakers use it express a sense of pity, but with tenderness)" And so it was that, like, "How do I get readers to care about them both?" For what they bring, for what each character and any one person... Sometimes we're compelled by the loudest sob story. And I think that could have easily been Camino's story, which is why I think I gave her a ferocity of spirit and a lot of people around her so that it didn't feel just like, "Oh, here's this poor little girl," like, "Oh my god, the Dominican Republic is full of orphans." No, this is one story. It's just one glimpse.

EdlC: And one other thing too is that I think this might... I hope… it's probably true of every town, you go to Moca, Villa Tapia, Santiago, whatever, there's always characters like El Cero, for instance. Which to me, believe it or not, while Papi was looming large in the story, he's another character that's the villain. There's an omnipresence about this guy that is dangerous. I didn't even know what to ask you about this character. What were your inspirations behind him? And did he change throughout your writing process at all? El Cero.

EA: He did, he did. El Cero, which is short for "carnicero" (butcher)— people think it's "cero" as in "zero," which also works, but literally "carnicero" I thought was even more symbolic of what he represents.

Prostitution is legal in the Dominican Republic, however a brothel or pimping or any type of other individual outside of the two people, or whatever the transaction is, isn't allowed. And that becomes a really big thing when you're talking about under-aged girls, or just girls right? All girls underage. And when I was doing work specifically with young women in DR, that was one of the things that the organizations all had to struggle with, that there are men that are going to come around and offer these girls, like, "Why do you have to go to a high school two towns away? Wake up at six in the morning to get bused there? I'll pay you this weekend however much money, you don't have to work again until next month."

And so it's this allure of young women who are in completely disenfranchised positions. It's so normalized in some ways that you have these outside foundations stepping in. And so it was less about... It was just something that struck me. Like, when you are put in a position where these are the options, what happens to you?

It's a book about silence. So it's important that we're not talking about silence, we're talking about shame. I'm never going to tell any kid, "There's something too shameful for me to talk about."

And so Cero represented a lack of options. And it's not that there's anything wrong with sex work if that is what you choose to do, but it is a choice, right? And someone who is underage cannot make that choice. And when are we going to start having these conversations around how age is treated depending on setting? If you were taking Yahaira's 16 in New York, we're talking about someone who was trying to pimp her out, we would be like, "Wait, this is a sex ring, this is..." Hopefully it would be a thing. Well when you talk about other countries were it's like, "Well those are pleasure places, we kind of hands off, that's tourism, that's our bread and butter. People will figure it out."

So Cero represents that. And yeah, I had to—similar with the Papi character, I cannot make a monster out of people. That is not what I'm looking to do. And so you learn a little bit about his little sister, you learn that there's some trauma there. But then he's working within a system, and there are other people involved too. There are other men, there's a resort. This is all an ecosystem. He is just one person we are looking at within the ecosystem. So I don't want to pin anything on one person because the idea is if we just get rid of this person everything's okay. And that's not the answer, it's like, institutionally, how do we undo the ways that our countries function?

Which is a really grand idea to have for a YA novel in verse. But at least start the conversation. At least start the conversation, right?

EdlC: Absolutely. Gosh, you said so much that I have questions on, but primarily, and speaking of Cero's character and this being a YA novel, did you restrain yourself at all in writing about El Cero? Were there things that you said, "I can't go there with these girls?"

EA: There wasn't any point where I said, "I can't go here because it's YA." I think that young people... The things that happen in the book are things that happen. The train scene is a thing that happens, it's a thing that happened to me. The ways that women have to hold each other, the ways that people keep secrets: all of this happens.

So for me, I don't ever want to shy from being honest. I think kids are having these conversations, kids are watching each other be coerced into situations, they're watching older guys come around their schools. If you watch the R. Kelly documentary you realize that this is the way that young women and black women, and women and color, and immigrant children, are kind of shoveled to the sidelines. And things happen that they can never say because they feel like they cannot be protected from them. It’s horrific.

And so I think it's important to have these conversations, to talk about like, "What would have happened if Camino had said something sooner? Why didn't she trust Tía, who is her rock, to hold that down? What was she trying to protect Tía from in that moment? What if Yahaira had talked to her mother first?" It's a book about silence. So it's important that we're not talking about silence, we're talking about shame.

I'm never going to tell any kid, "There's something too shameful for me to talk about." But I do think that I am careful on… if I'm going to bring kids on a journey with me, or any reader, because I'm writing YA, I am thinking about, "This has to be something a young person can handle." I knew I didn't want there to be rape. I knew that was a possibility and it kind of hangs over the story as a possibility. So I always had my niche on, "This could be the story but that's not the story I'm choosing to tell. We're going to just let that hang over the story, it's the umbrella that everyone kind of knows. This is what's possible and this is what may happen."

But in the one that I'm telling, it felt like there was already enough hurt and trauma. That there were things that I'm sure could have been possible in the story, but they weren't necessary. So I think I bumped up just against what is necessary to get the point across of just how real a lot of this is, without necessarily needing shock value.

So I pulled back a little bit, but… No, I probably could be a little bit... No, that's not true. I'm working on being my honest, unflinching self, and I think that's what kids respect. Adults love the books, but I think kids love the books because they're like, "Wait, she don't hold no punches."

EdlC: Right. I felt that way when you brought up Yahaira's sexuality, or when Yahaira revealed her sexuality to Camino. Camino deflected it as, "Oh, I know homosexuality is difficult in Dominican Republic." But she accepted Yahaira, and that also resonated with me.

The other thing that I wanted to ask you about was Tía's character. There was a moment in the novel where you describe her as once being beautiful. And when that verse started I immediately wanted to know more about Tía. But then it went away, and I don't think you came back to it.

In relation to El Cero’s character, what does La Tía really represent, knowing that Camino's mother is no longer around?

EA: I think if El Cero represents an illness in the society, or a diseased part of the society, Tía literally represents the healing. She is someone who could lead that neighborhood, who could go on to a different life, who was offered that opportunity. But who's so dedicated to, "This is where I'm from, and if we don't have these resources someone needs to step in."

And I think that that community spirit... There's always one character in every one of my books who's like, "It is actually okay to stay home. It is okay if you do not leave this place." We are told stories of, "You have to go to the 'burbs and get these big-ass houses, and this is the only way to prove success." And I always want to counter that with the one character who's like, "I love where I'm from, and I'm going to sit here and make it better."

Because I think we have to talk about homes as being places that some people desperately want to leave, and that they realize, "I cannot grow here." And as places that other people realize, "I have a role and I have to fulfill that role. There's a duty to this community that if I don't it, someone won't."

It's just about the juxtaposition there. But I think Tía's character represents so much. I love the hairy upper lip, but that she was beautiful. And that she does carry this machete. But also when I was writing her there were things that would come out of her mouth that I would be like, "Yo, someone said that to me." When she's like, "Don't ever talk about death as if it's a sure thing." Those little sayings that women in my family will say like it's nothing, but that really hit home. And I'm like, "She is the embodiment of a collective wisdom." We learn from each other, we learn from doing it, and that is a sacred thing.

Like "Yes, Camino with your textbooks and your doctors and your dream of Columbia, tato, pero like we also have to know what herb works." And sometimes you overthink things. I like the idea of the figure who comes in and isn't the witch doctor that saves the day because she can't do that, but is bringing in—outside of technology, outside of these other things—is just bringing in a different perspective. In The Poet X we have the priest who kind of comes in and is like, "How do we heal from within? We don't need outside people, we don't need anything out there. We can figure it out at home."

And I think for me, Tía was that. "We will handle us, we take care of our house." It's wishful, but when I look at certain issues and issues I'm writing about, to imagine that the societal ills will end with a policy change, it’s like, "Not until people start doing that work themselves." And I think when you're writing, particularly about areas that are forgotten, if you don't step in… I just think that community spirit is one I want to see more invoked. I want people thinking of place in that way.

EdlC: So Elizabeth, this novel further illustrates the importance of own voices stories, something that's become increasingly acknowledged as important in the literary world. What have you thought about some of the controversies around who gets to tell what stories?

EA: I think that craft shows a lot. And I feel like some people believe they have the range to tell certain stories. And it's important to just feel like you've done the work, right? And I think research is what you find online—I did a lot of online research, I watched a lot of documentaries specifically on the flight. I went to Sosua, I worked with young... I did a lot of setting the ground because I knew that there were points that were outside of my understanding.

We had a babalawo read the book and make sure that the Santeria felt specific. I had Haitian readers. My Dominican cousins who were raised in DR read it to make sure that I wasn't... You know? So this is me writing as a Dominican, and still realizing there are a lot of things I don't know that I need to make sure I get right, because if not there are so few books by Dominicans about Dominicans put on the market that I owe it to do as much work as I can. And I might get it wrong. I might get some things wrong.

Sometimes when we talk about own voices, when folks are writing outside of their experience, I wish that there was just that dedication to... Writing a people requires proximity to a people. And that doesn't mean you can't do it, and I would never tell anybody... I'm writing stories about folks I don't necessarily... I'm not that. I didn't lose someone on that flight. But you have to know them.

I always love using the example of, Dominicans point with their lips, "Pásame eso (give me that)."

EdlC: That's so true.

EA: And I thought that was universal. And my husband one day looked at me, was like, "Why do always do that thing with your mouth?"

But it's that. It's like, "If I do not know those gestures, how am I writing this?" My second novel is Afro-Puerto Rican and Philadelphian, a teen mom—that felt super outside of my lane. And she's still Afro-Latina. And so I had to then go back to, "Okay, what are the perceptions and biases I've learned about Puerto Ricans? What is it that I know? How am I making sure I'm not carrying that into this book? Am I doing it justice? Have there been other books written about Puerto Ricans and enough of those that I feel like I'm not taking up space?"

It's all of these conversations, and I feel like sometimes people want to skip those steps because they have a cool idea. I've got a lot of cool ideas that I realize aren't mine. Like, that is dope but I might not be the best person because: the research I would have to do? I'm not dedicating 60 years to live in that place to figure that thing out. And I think sometimes people shy away from the work that is required of them to not do harm to a community of people.

One, you've got to do the work. And two, you've got to take your lumps. You know, someone comes at me and it's like, "Bueno you didn't lose anybody on that flight and I don't think you wrote grief right," that's fair. I didn't lose anybody on that flight and if the grief didn't resonate, that's fair. You know what I'm saying? And I have to be able to own that. I was writing outside of my lane, I tried my best to extend my imagination, and that possibly it didn't work.

That's what I've got for own voices. This gets really complicated. But we could parse it apart until at some point you're not writing fiction if you're only writing what you know. So I just want to push to write what you know and then be incredibly mindful about what you don't know. And be willing to do the work to fill that gap, and also realize that there might be gaps you don't even know you have that come out after publication. That's the project of writing fiction. And the craft will show; if you didn't do the research it's going to be thin.

EdlC: Well I have to say that you were on point when you described in the novel the scene with the sancocho. In the waiting for Yahaira's arrival. That rang so true to me.

EA: And I included every step. Like, that was one where you got the whole recipe. It takes many hours, you need this much. I wanted those parts of us that another Dominican reading would be like, "Word. Word."

EdlC: And even further, Elizabeth, there was a point in time when you... I think you ended it with heart at the end of that sentence. Which to a sancocho is... For the listeners out there, sancocho is our most familiar recipe that we make in every possible occasion. It could be 90 degrees outside but we still have sancocho. And a lot of us here in the States use it as a hangover cure, if you can find a restaurant for it. Or I can make it. But it was an incredible touch of detail that hit home for me, the sancocho bit.

EA: I write a lot about food. It’s so nice to see the comments because people will comment a lot on, "This book has just as much food as the other ones." And I'm like, "Is that my thing? Is that what I'm known for now?"

The sancocho takes so much time. And it takes so much effort and it really is such a sign of love. And it's hot work. And so the vats, when you see those big-ass pots of sancocho, you have arrived. For me, I'll go to New York and my mom will make it for me all the time because... I don't eat meat, but that's the one time when I'll be like, "Esperate!" I’m vegetarian, so she thinks of me now. But it's still like, broth, right? Con tó la yuca y tó lo plátano (with all the yuca and platáno, the two main root vegetables used in the dish). But it's our way of being like, "Yo, I love you and you're home."

And so when I go to DR and that is the first meal, it is like you said, here is this gesture somewhere else, but it's that same... I want you well and so I gave you the thing that cures all hangovers and cures homesickness, and cures everything.

EdlC: It cures everything. There's also something else you said too, you wrote, "The patience pays off in the end with a sancocho." It takes time, but in the end it pays off. Elizabeth, another question for you. Are there any plans to translate your work into Spanish for Latin America?

EA: Yes, The Poet X was translated, and that was done by Ediciones Urano which has a base in Argentina and a base in Spain. We are in conversation with them to try to see for the other two novels. It is an interesting field to step into because there's a lot of Spanish in the books. And I'm writing from a very Caribbean perspective. And so with the translation it's just trying to find the right translator.

I think because most foreign rights are trying to cover a lot of different countries, it's been hard to figure out the right middle ground of how do we send a book to Chile that is going to understand a bunch of Dominican-isms? But also it's important to me that even in Spanish the books sound like me and sound like what I'm writing about and from.

So we are in conversation, but we'll see. I think folks are reluctant to use non-Spain translators. And I am reluctant.

EdlC: Well the saving grace is that Dominicans are everywhere in Latin America. They're in Spain, they're in Chile, they're in Argentina. They're everywhere.

EA: I just want to disrupt what we think neutral Spanish is. I'm pushing, and I think they're open to it. We just got to figure out what it's going to look like. There should be a Spanish version, and if there isn't it's because we haven't been able to find the right person. So stay tuned folks.

EdlC: speaking of the Caribbean experience, what do you think unites Caribbeans as people?

EA: You know, I'm always so surprised to receive notes or DMs or messages from people who will read one of the novels and really resonate. And then they tell me where they're from and it's like, all over. It's Antigua, Barbados. But they come to me and they're like, "This feels so Caribbean." There's something about that experience of writing. And so I do think that there's clearly a thread that does connect us. And part of that is probably, geographically, we are in a lot of continental shadows.

When your island’s descended I think there's just a different understanding of fluidity and joy, because you are existing with much smaller territory. The idea of just like, you could just go across the country and that's a big continental flight, versus my mom would get on a plane for 20 minutes and go to Puerto Rico and then come back that same day? It's just a different understanding of region and of closeness and of people.

When your history has been islands communicating with each other—so many Dominicans in Puerto Rico, so many Dominicans in Antigua. We share folks. And so there has to be a lot that has been fluid.

But I'll say that the thing that... Not that unites us, but one thing that I feel like I see a lot of Caribbean writers slightly pushing back against is the idea that the Caribbean is the globe's playground. That we are just here to be palm trees and sunlight for everyone else. And I think a lot of folks are trying to continue amplifying the voices that say, "We are powerful and our narratives are deserving of being told in our way and in our voice."

EdlC: Well with that, Elizabeth, I want to thank you so much for spending time with us today. For everyone listening, Clap When You Land is available on Audible. Please listen to it, you will not regret it. Thank you so much Elizabeth.

EA: Thank you so much everyone.