Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

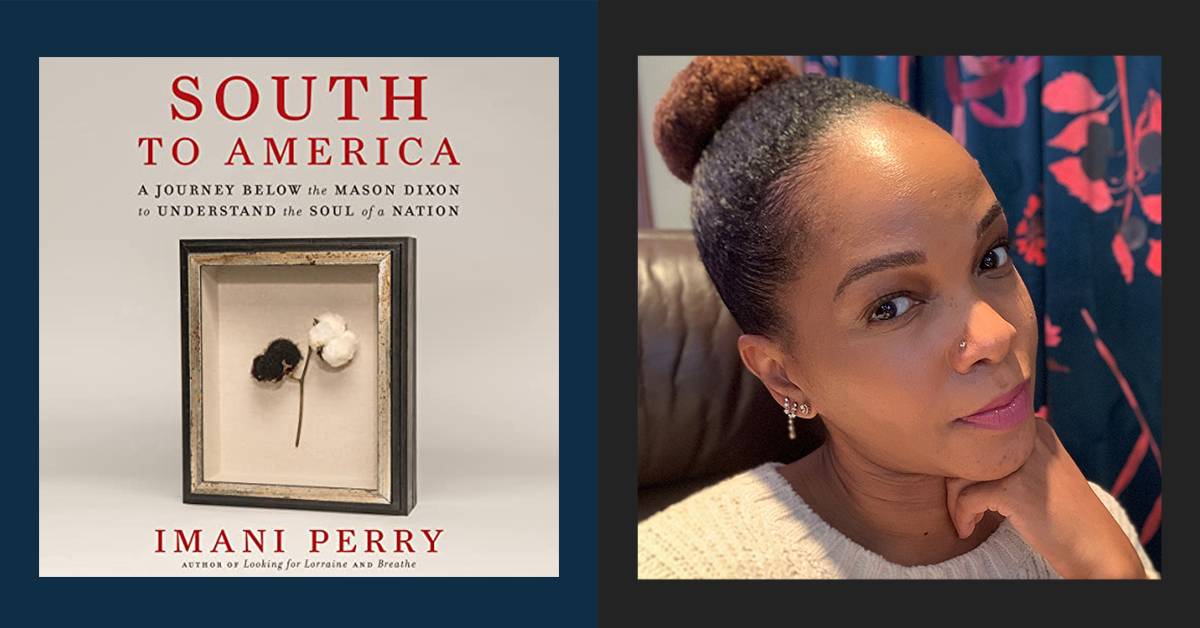

Christina Harcar: Good morning. I'm Christina Harcar, Audible's history editor, and today I have the distinct pleasure of speaking with Imani Perry, a legal scholar, professor, and author. Listeners may already be familiar with her work, such as Breathe: A Letter to My Sons, and today we're going to talk about South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation. Welcome, Imani Perry.

Imani Perry: Good morning. Thank you so much for having me, Christina. I'm delighted.

CH: So I'm going to dive into my first question, which is a general one I tend to ask a lot of authors. How would you summarize South to America in one sentence for listeners who are new to your work?

IP: Wow, that's a great question. I'd say it's a journey of discovery, surprise, and revelation about the soul of our country.

CH: I think that is a wonderfully inspiring capsule, and having read your book, I completely agree. From my experience in publishing, it's sometimes really hard to come up with a title that encompasses a lot of places, ideas, experiences, and emotion, and your book is rife with all of these. I'm curious about the title, which is perfect. Was that easy to arrive at, or how did you arrive at it, or was the title a journey in and of itself?

IP: I did not arrive at the title. It was the good folks at Ecco who came up with the title. The ideas I had were much more flowery and abstract, but I think immediately when "South to America" came up, it resonated with me, it resonated with everybody who was part of the community working on the book, because, of course, books are community productions, even though there is the author.

"...There's something really honest about the human condition that comes through the blues. It's not incidental that so much of the blues comes out of prisons for that reason."

And part of what made it resonate is that the story is about the United States of America, but it's also about the Americas. It's about the South as a region that is produced by the intersection between the transatlantic slave trade, Indigenous communities and their dispossession, and European powers, global powers; the sort of effort to harness the land that is often so cruel, but also becomes the space where cultures and innovations are born, and so America is this sort of vast term. South is a vast term. We talk about the Global South. We talk about the South as the largest region of the United States. It was a title that was able to capture the complexity of the book and its specificity. I fell in love with it immediately and was so happy for the suggestion.

CH: Yes, it's a wonderful title. Let's dive into talking about this audiobook a little bit. I was completely drawn to almost every place you discussed. Your evocation of place was magical for me. I actually felt like I was on a journey as I went along with you, and I was curious, what was your favorite place to explore in the making of this story?

IP: Oh goodness, what a question. I'm going to get emotional because my favorite place to explore is always my home, Birmingham, Alabama. It is always home. It is a place that is so historically significant for this nation, for the revolution of the mid-20th century. I was born just nine years after the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, just seven years after the passage of the Voting Rights Act, which, of course, is more Alabama history than anything else, and yet it's an everyday place. It's a place where I learned to speak, where I learned to walk, where I learned to read. I'm endlessly fascinated and in love with my home, notwithstanding all of the painful parts of our history.

CH: That definitely came through, and I think a lot of us are in love with your home now. I was particularly touched by your discussion in that section about the blues. I have enjoyed before your work on Lorraine Hansberry and essays that you've written about music. I understand that people often use this very big word "interdisciplinary," which I kind of think of it as just heartfelt as you go through it.

IP: Right.

CH: I wondered if you could say something about what it was like to be in your home with what you just said, and to be examining the blues through the lens of this soul of a nation?

IP: Oh, thank you, Christina. I appreciate what you said, because intellectual work to me is always hard work. The way in which we separate that out I think has a huge cost because we are passionate about ideas because of our hearts, and we put our minds to that passion. So the blues for me are, it's this sound that is an ancestral sound and it continues. It's waned in popularity, but it's still there, and it is a sound of the crossroads between Europe and West Africa.

It is the sound of people who were deeply connected to the land in vexing, difficult ways. I think this is true for rural people around the world. And very much so for Southerners, music has this function that is healing, that is cathartic, that is imaginative; it gives all of these ways of experiencing humanity that are possible without a lot of resources, without the proximity of major cities, and so there's something really honest about the human condition that comes through the blues. It's not incidental that so much of the blues comes out of prisons for that reason.

And also through migration, the Great Migration, of course, but also the migration of labor, so I think one of the things people forget is how much of Southern history includes migrant labor, and people moving around and having this guitar you can travel around with and tell stories and encounter other people and forge connections. The heart of a nation has to do with encounter, right? An encounter is a complicated concept: we meet the land, we meet labor, we meet force, we meet brutality.

These encounters become the stuff out of which we become a collective people, a common people. Even with very different social locations there is something about what it means to be American in there. I should also say that my mentor in this work, who I never met but who shaped what I think, is Albert Murray, who was a brilliant writer on the blues, and I feel like he sort of guided me through this book at least spiritually.

CH: I can feel that, and I just have to say on a personal note, when I finished that section I went back and listened to B.B. King's version, and Bobby "Blue" Bland's "I'll Take Care of You." It sounded new to me and very different, and I really connected with it in a new way, and I wanted to thank you for that.

IP: Oh, thank you.

CH: So leaving Alabama for a second—thank you for telling me about your favorite place to write about—what you said about it being your home made me realize that my favorite place that you wrote about, two places, I loved the chapter "Pearls Before Swine." My home is in New Jersey; I grew up 17 miles north of Princeton. So in the same way we all don't believe in horoscopes, but we turn to our horoscope in the newspaper, this was the chapter that drew me and it didn't disappoint. I went into it thinking that I knew Princeton, the town, and the history of the university, and I ended up learning so much about a place that I consider home, and also discovering Nashville through your work.

Long introduction, but I wanted to invite you to talk about Pearl High School a little bit, because I also found that to be a very touching discovery, or just a touching encounter.

IP: Yeah, I love the kind of moment of kismet. I start the chapter in Princeton, and my traveling between Philadelphia and Princeton on a daily basis, and Princeton having been historically known as the "Southern Ivy" for a bunch of different reasons, but part because the planter class of the South would send their sons to Princeton. They could bring slaves to Princeton. There are numerous stories of that, there were auctions on campus, and the like.

This is a story that I'm always sort of thinking about, that James Baldwin described going to Princeton as his first time traveling to the South, when he worked as a teenager and the experience of segregation in Princeton. And then it pivots to the Department of African American Studies, and the story—and I'm going to try to encapsulate it—is that I went to Nashville to deliver a talk at Vanderbilt, and I wanted to visit the home that my grandmother lived in when she was a teenager in Nashville with her aunt, and also her high school, and in the process of telling this story to my colleagues I found that three of my colleagues in the Department of African American Studies at Princeton also had family members who went to this high school in Nashville: Pearl High. What was remarkable about that is none of us are from Nashville.

"Part of why I think the story of the South is the story of the nation is it has to do with environment, it has to do with land, it has to do with 'This is where there is all this abundance,' and the question of, 'How is this abundance going to be harnessed for the building of a nation?' and, 'Who is going to be made to suffer for that?'"

I'm from Birmingham, Professor Eddie Glaude is from Mississippi, Keeanga-Yamhatta Taylor is from Dallas, and Reena Goldthree is from, well, her family is Alabaman, but she's from Missouri, and so none of us are from Nashville, and this discovery that they all went to this high school—you know, family members, parents, or grandparents—the discovery for me was realizing that Pearl High in Nashville was one of these exceptional schools, in the context of the Jim Crow South, that was superb. It really was one of these sites where you can understand how much education was cherished, and how much communities devoted to ensuring, even in the context of Jim Crow, that Black children would have access to quality education, that that was a primary driver.

And so, it's a submerged connection. Unless I had been digging around, who would know that we had these family members who went to the same high school? It's also not the simple kind of bourgeois story of like, "Oh, they went to this fancy Black high school," because my grandmother didn't finish high school, Professor Glaude's grandmothers didn't finish high school, but there was something about these types of institutions that planted seeds, that shaped how we all ended up at Princeton.

Once you start digging, you get different kinds of connections, these sort of veins and arteries to understand the making of institutions, the making of fields. I'm really captivated by that in particular because I teach in African American studies, into the sort of, "How does this field come to be," is a story of protest in the '70s, but it's a much deeper story of the long effort for African Americans to write their history into this country.

CH: Right. I love the "submerged connection" phrase. I'm curious, as this audiobook comes to be in the world I suspect that more people are going to be coming forward.

IP: Oh absolutely.

CH: That is so exciting.

IP: Absolutely. I posted a picture of Pearl, and one of my students said, "I went to Pearl." Another student said, "My grandmother went to Pearl," from Princeton students, and the filmmaker Dee Rees, I was talking to her about it, and she said, "Oh yeah, my parents went to Pearl." Yeah, it's already happening. It'll happen more, and I think it'll happen with other places and institutions in the book too, so I'm excited about that.

CH: As I'm chatting with you, I'm really delighted and inspired by this idea of the submerged connection, because it's inviting and it's hopeful, this idea that as a society we're at a crossroads, but there's actually some kind of scaffolding or network, or some way to make it better that is there. I did agree with the copy that the wonderful folks at Ecco wrote about your book, that it makes the case that to be American is to be in some small way Southern. But I also in talking to you want listeners to know that in that way that great writing does, the specificity of your experience starts to feel a lot like my experience too, and it's really satisfying.

IP: Oh, thank you. That resonates deeply with me because I do think that resonance is always the thing you're seeking as a writer, right? We have very specific experiences, but we want to render them in ways that they can be familiar enough that you can connect it with something in your own life, so, thank you.

CH: You're welcome. So, where we find our connection at Audible often, usually, stock in trade, is listening, and it's wonderful to speak to an author who is also a narrator. This is not the first book of yours that you have narrated. The personal connection comes not just through your words, but through your voice, and so I wanted to ask you, what does it feel like for you when you narrate this book, when you perform the words that you've written?

IP: Let me start by saying it is an arduous process, it's really a labor of love. I was eating teaspoons of manuka honey through the day. It's emotional. There were several moments when I just broke down and it took me a while to pull myself together. I was just overwhelmed by tears unexpectedly. And then there's the thing about language and pronunciation. I'm someone who code-switches, meaning sort of code-switches between African American vernacular English and standard English, but also regional speech patterns, but there are also pronunciations, especially for words that are like core words that are very Southern, even though I left the South young.

And so there were moments where the producer would interrupt me and say, "This is actually pronounced this way," and I'd be like, "Well, I've pronounced it this way my whole life, and it's a book that is about the South, so we're just gonna have to rock with it the way I said it." It becomes a kind of mirror to who you are and your own formation when people are hearing you, or noticing, that I don't say "tornado," I say "tornada," or "tabacca," or "Appalachian"—that there are words that when you've heard them from the very beginning, even when your language shifts, those words don't shift. So that's interesting.

CH: It is interesting, and it's part of the weave that gives realness to the voice, so I think that that is a wonderful observation to make about narration. Before I segue into the next subject, I have to point out to any listeners who are hearing this that the colleagues you mentioned… Eddie Glaude is the author of one of my favorite books of, it feels like a lifetime ago, but it was last year, which is about James Baldwin and reconceptualizing what he said in the modern era and a completely stirring book [Begin Again], and a personal signpost for me, and I encourage listeners to find it in our store, and also From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation by Keeanga-Yamhatta Taylor. I think my point is it's very meta. We're talking about connection, and connection through listening, and connection with your colleagues, and, you know, they're all authors, and they're all in our store, and this connection is available to us, and that is a happy thing.

IP: Yes. I'd like to make this point just because of the way the South and Southerners are characterized: those books that they wrote are so transformative and groundbreaking, and it's not incidental that at this moment there are people who are coming out of the South who are really key for helping us understand where we are. That's the meta point of the book. There's an intimacy with the core of our foundational challenges that people who come of age in the South are connected to, and so once there's a sort of interrogation of that experience, I think that a lot gets illuminated.

"Everything I write is geared towards a belief in the possibility of the beloved community; against all evidence otherwise, we try to hope for something better."

So, they're really important both as interlocutors, conservation partners with me, but also they have both the intellect and the experience that really helps us get it.

CH: Yes, thank you for making that point. On a side note too, I grew up in New Jersey being taught that there was a consideration to run the Mason-Dixon Line through New Jersey. This book made me totally rethink. Is that true? What would that mean? And on any given day I could be pro and con. I just wanted to throw that in there and say you're right, and when you talk about the South, again, everyone has a South in them to some extent, and the experience of hearing your words will make listeners think. It's almost like the concept of true north; now we have true south. "What is your true south, and what does it mean?"

IP: I think both because Jersey has a longer process of getting rid of slavery amongst Northern states, and also when you travel through those towns in South Jersey that are sort of plantation towns—I mean, they're not called plantation towns, they're farm towns—but the way they were run historically, and the kind of poor communities as you go farther down in Jersey, you can feel that dynamic of both race and class and land that is not wholly different from the South.

Part of why I think the story of the South is the story of the nation is it has to do with environment, it has to do with land, it has to do with "This is where there is all this abundance," and the question of, "How is this abundance going to be harnessed for the building of a nation?" and, "Who is going to be made to suffer for that?" So it's not like a mystical thing about the Southern soul. It's about what is produced there, and there's aspects of that in other regions, and so I get it with Jersey. You can understand, given the agricultural history of the state, why it has shared some characteristics with the South.

CH: Absolutely. I think that you have already mentioned this in a lot of different ways, but I really would love to underline it and tie it up with a bow for our listeners. What is your fondest hope of what listeners will take away from listening to this audiobook?

IP: I hope that they will take some stories away that are unforgettable. Some of the episodes, some of the events, some of the characters. I hope they will be encouraged to look upon the region, and themselves and the nation, with fresh eyes, and I hope that it will actually elicit hope. There is something about all of the difficulty, you know, [being] salt of the earth, earnest, and also imaginative people—that's where hope for our future resides, and so I hope as opposed to seeing, "Okay, the South is this sort of weird, backwards, different place," that it actually ignites the imagination and tons of possibility. That's something that we can do meaningful things with together.

Everything I write is geared towards a belief in the possibility of the beloved community; against all evidence otherwise, we try to hope for something better, so, I guess, that's the thing: I want that part to speak to listeners.

CH: Thank you for that answer. I love what you just said about the hopefulness of the beloved community in all of your work, and I wonder if I can ask you, do you think that that's the through line over all of your work?

IP: Oh yes. And that is really a breach of academic culture, right? Because academic culture is so often about being right and not about being good—and not good in the sense of Goody Two-shoes good, but good in terms of being devoted to the good, the collective good. This is my parents, this is my grandmother, this is my tradition. I would not expend so much intellectual and emotional energy, labor, were it not in the service of what I think of as the good directly trying to address human suffering and being motivated by love for humanity, and love for the planet, and love for young people, and elders as well. I have children, and I think about, "What is this thing that we have, we are leaving them with? How can we try to, if not repair, give them something that helps them imagine differently?" That's the through line, absolutely.

"The South as being a gateway to the rest of the world is something that is often neglected in the story about the South."

CH: Yes, that came across really strongly in Breathe.

IP: Thank you.

CH: And now that I'm sitting here, I think that that's also true of your Lorraine Hansberry book and the musical work.

IP: Yeah. Hansberry is and was a muse because she was as impassioned to build a better world as she was intellectually voracious, as she was a brilliant artist, and so she's like a model.

CH: In talking about your work, do you feel like sharing what you're working on now?

IP: Sure, yeah. Well, I'm working on a couple of things. It's so funny, one of the things people ask, "How long does it take you to write a book?" That's an impossible question for me to answer, because I'm always working on multiple ideas at once. The other day someone asked me, "How'd you begin South to America?" and I'm like, "I've been writing it my whole life." There's notes that I've taken since childhood that are part of what this could become, so I will say this is not everything I'm working on, but one of the things that I'm working on is a meditation on the color blue in Black life. It's a passion project, but it's also connected to what we were talking about with the blues, and what does it mean to give a sound to the world's favorite color and to try to move through that and also why blue is such an important color for people who are imagining freedom, you know, the sky and water. So, that's one of the things. And I'm working on some middle-grade works, which I'm really excited about, and I do have an Audible project that I will save discussion for, but I hope people will look out for.

CH: Terrific, thank you for sharing all of that. I'm very excited about "Imani Perry's Kind of Blue"—I don't know about the working title. Before we go, is there anything else you want to tell listeners about South to America?

IP: I would say another piece of what I'm trying to say about the South that's really important, and it comes towards the end of the book, and because it's a long book it'll take a while for listeners to get to it, so I just want to mention it: the South as being a gateway to the rest of the world is something that is often neglected in the story about the South. People think of these Northern or Western cosmopolitan cities, but, you know, the South is part of the Circum-Caribbean.

The South is where oil was struck, and so that connects the United States to the world. The South is the entry point of what the relationship between the United States and Central America has been, and Mexico has been, and the Caribbean has been, and so there's so many ways that there are other regions that have been created through and with and under the influence of the South that we often forget those connections, and so I try to go into telling stories. For example, why is it that Central America was once offensively called a place of banana republics? That's a Southern story. Why is that we became a car culture? That's a Southern story. Detroit is essential, but oil was necessary for that, right? That's a Southern story. I want people to listen through, and I think it's a perfect work for a slow progress through. It doesn't need to be rushed. There's a lot on each page, but there are, I think, lots of surprises all the way to the end.

CH: I completely agree with that, and that the journey is the destination.

IP: Yes, that's beautifully stated.

CH: Your audiobook evoked that for me, and I just want to thank you from the bottom of my heart for your wide-ranging thoughts, and your wisdom, and the glory of the words, but also for your time today. It's been a pleasure, and "thank you for stopping in," I guess, is how we say it now in these digital times.

IP: Thank you so much. It's really been a delight to speak with you.

CH: We'll be rooting for the success of your book, and in fact, let me just say that listeners can download the audiobook South to America at Audible.com now.

IP: Thank you.