Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

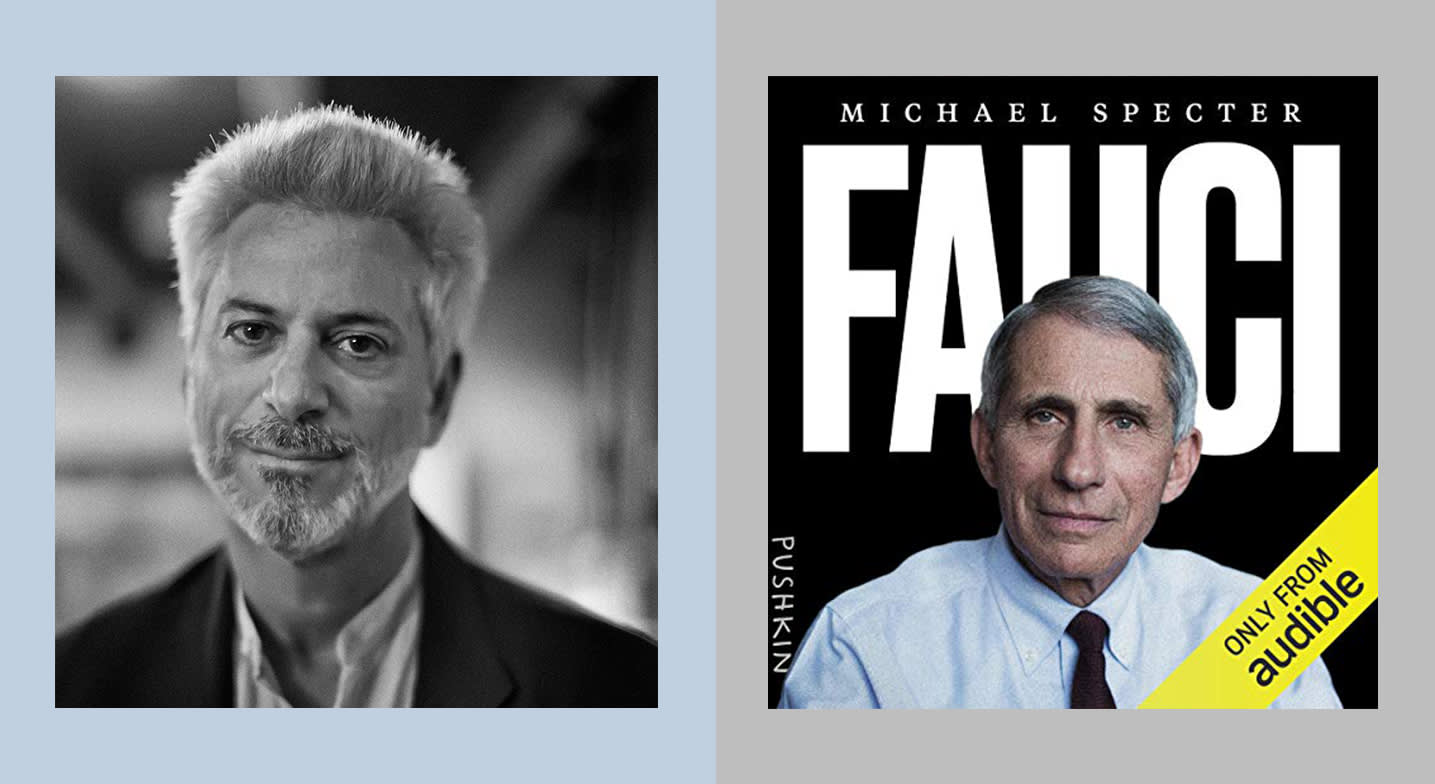

Courtney Reimer: Hi, I'm Audible Editor Courtney Reimer and I am so glad to be speaking today to Michael Specter, the journalist, author, and narrator of the new audio exclusive title Fauci. Welcome, Michael.

Michael Specter: Thanks for having me.

CR: So it's particularly serendipitous that we're speaking now because Dr. Anthony Fauci is, of course, in the headlines as he has been for some time now, but with the two vaccines having very positive results so far, we're seeing Fauci back on the talk shows and weighing in. So this title is going to be in the forefront of people's minds again.

MS: That's good to know.

CR: So you go way back with Anthony, or Tony, as some people call him. You are well positioned to craft this multilayered audio portrait of possibly one of the best-known names of these unprecedented times. Can you talk to me a bit about your history with Dr. Fauci and where it is now?

MS: Yeah, I met him in 1986, which was about a year and a half after he became the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which he has directed ever since. I was working for The Washington Post and I had been assigned to cover the AIDS epidemic, which was raging and they had never had a reporter just write about AIDS before. And Fauci was the kind of go-to guy for the federal government on talking about AIDS.

"...The people who were the most active AIDS activists... went from detesting Fauci more than anything on earth to absolutely loving him. And that's because he just listened. That sounds pretty simple, but it's kind of rare."

So I immediately met him and I dealt with him quite regularly for the next two or three years as I covered that beat. And then over the years, I worked at The New York Times for a while and I'm at The New Yorker now. I've done a few different things. I've lived overseas a bit, but I've always gone back to writing about science and medicine. And I've had a particular obsession with pandemic preparedness and influenza, and so has Fauci. And so we have intersected on any number of pandemics and I've had many long conversations with him over the years about how you deal with this, what would be nice about dealing with that, this sort of thing.

CR: So let's talk about that. Fauci is, he's practically a celebrity at this point. But folks who've been around a little longer may recall, you mentioned the AIDS epidemic and how he started to become part of the public consciousness back then. And as he is now, he was then a controversial figure of sorts to some folks.

MS: Yeah, he was very controversial. First of all, he emerged as a sort of classic bench scientist, a guy who had done some really important research and he got wind of the epidemic early and decided to focus on it. But the federal government didn't do the job it ought to have done in terms of helping the people who were infected, particularly because they were homosexuals mostly.

And Fauci bore the brunt of that because he was the most famous person associated with the epidemic. It got very ugly for a while and at one point Fauci thought, "This doesn't make sense, I'm trying to help them." So most people in that position would say, "Get lost, we're done with you." And that's what a lot of people at NIH did and wanted him to do. Instead, Fauci just went out and met all the ACT UP [AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power] people who were the AIDS activists and said, what's your problem? And when he asked them that and they answered, his response was, "Oh my god! You're totally right."

And he completely changed his position and kind of became a leader that they could look up to and work with. And that is very unusual. We don't have a lot of people changing their minds anywhere ever. But to do so in such a very public way, it was kind of remarkable to watch it then. It's always been a remarkable facet of his character and the people who were the most active AIDS activists, particularly a guy named Larry Kramer, who I bring up a lot in this audiobook and who I've written about and known for decades, who died this year, they went from detesting Fauci more than anything on earth to absolutely loving him. And that's because he just listened. That sounds pretty simple, but it's kind of rare.

CR: You just used the word "remarkable." It truly is. I can't think of any other example of such a public figure actually stopping to listen to their critics and—

MS: It doesn't happen very often and, I think, sadly, it happens less now than it used to. And again, I think Fauci is, first of all he's driven by public service. That guy has worked there for a long time and he gets paid very well. But he could get paid multiple times what he gets paid if that was something that interested him if he had left his job. I think he does the job because he cares.

And he has taken a lot of crap, frankly. The things that people have said about him during this pandemic are breathtaking. He has had death threats. You can think whatever you want about the guy, but he gets up in the morning just trying to get rid of a terrible thing that's happening to the American people. And for him, his wife [Christine Grady], and his adult children to be put in danger in this way, it says a lot of bad things about our country, I have to say.

CR: So I think you do a great job of humanizing him in this to that point of he views his role as one of service. Talk to me a little bit about how you went about capturing the Tony that you know. I think about him out on a walk, that audio that you captured.

MS: Well, at the beginning of this book we have a conversation where he's out walking with his wife. And we were originally, to be quite honest, we stopped that conversation because my producer was concerned that the quality of the sound wouldn't be good enough. And he was good with that too. He went home and we continued it from home.

But it was very revealing because he had been very frustrated about… That conversation occurred right after the president of the United States had sort of released an opposition research paper against him, which is something political opponents do to each other. You don't usually expect the president to do that to his top infectious disease expert. And Fauci saw the humor in it but it wasn't that funny, and he was kind of shocked by it.

So we had that conversation and then he went home. I talked to him, I talked to his wife, who's also quite a remarkable human being. She runs the Bioethics Division at the National Institutes of Health, which is a very complicated thing to do because as science progresses, those decisions about life and death and what to do with bioethics just get harder and harder.

And she's done a really good job, but she's also extremely fiercely protective of Tony and more so than he is of himself. And that, I think, probably came through in the interview that I had with her for this book and it comes through all the time if you talk to her.

CR: Yeah, wow! To be a fly on the wall. I wonder what their dinner conversations are like, when they finally get around to dinner that is, because I know he's also a workaholic. I'm really glad you included that audio of the walk with his wife, partly because you get the ambient sound and the kind of like rough-around-the-edges, because that was representative of how he was feeling and where he was in that moment.

This is more than just an audiobook. It's more than a podcast. It's sort of like a love child of the two. Talk to me a bit about the decisions you made in this area of audio journalism that's coming up.

MS: Okay, this is an interesting question, which I'll answer honestly but probably incompletely. So the people who run Pushkin, Jacob Weisberg and Malcolm Gladwell, are old friends of mine. And Malcolm and I worked together, we covered AIDS together at The Washington Post, we go back. And I wrote a long piece on Fauci for The New Yorker in the springtime.

And Jacob called me up and said, you should turn this into an audiobook. He also said, and I hope you use this part, it'll take you no time at all. And I said, fine. I was teaching at Stanford and I taught through June, the semesters are quarter systems so I had to teach through June. I said, I'll do it over the summer, if it'll take me no time, no problem.

"You can think whatever you want about the guy, but he gets up in the morning just trying to get rid of a terrible thing that's happening to the American people."

But it was a tremendously all-consuming project because I would write things and my very brilliant editor, Julia Barton, would read it and say, I'm sending this back to you and don't give me more stuff unless you read it out loud first, because New Yorker writing is nice and it's lovely writing usually, but you can't always say the words that you write.

Audio is an absolutely different medium and they're related, but they're different. And I had a couple of really unpleasant weeks before I figured that out. Of course, that was all I thought I would be spending on it. I actually spent the entire summer, every minute of it, doing it, and it was delightful. And I had a team of producers and editors who are just unbelievable.

They had seen the value of doing this as an audiobook because they knew we had great archival tape, AIDS, pandemic, all sorts of appearances that I had, had a lot of recorded interviews with Fauci over the years, and also with other people who appear in the book. And then they had a guy named Bart Warshaw, who wrote a score for it, which I didn't even think that would be possible. And music does alter everything. And it's a very subtle score, but it's beautiful and I think it really works.

I remember a friend of mine who's a film director saying, "Just with a couple of notes you can make somebody cry or change their mood entirely in a movie." And I do feel that, that is a very powerful element of this book. So when you put the interviews, the writing, the experience together with some really great sound in the type of pacing that frankly I never would have been able to do myself if I wasn't being taught by some people who really know what they're doing, I think it worked out well. I was extremely reluctant to listen to it, but I finally did. And I thought it came out pretty well.

CR: I agree. And we at Audible obviously agree that the audio format is extremely evocative and there's science and research around how sound can light up parts of your brain that even movies and visuals can't.

MS: I'd also say that since that audiobook has come out, I've had a lot of comments from people who, I feel like it fills a niche. I listen to audiobooks a lot. I'm heavily invested in Audible and I don't mean stock prices. They're usually eight or 10 hours or 12 hours, and that's okay because I'm cooking or I'm driving or something. This is three hours. And I think a three-to-five-hour book is a sweet spot for a lot of people, they feel that it's quite digestible, yet you get a lot of information.

CR: Kudos to you and everyone who peppered throughout sound bites that really helped drive it home. And even though the author of this is Michael Specter, you get Fauci's voice, you get him in interviews. So you really get a sense more than if I were just to read a quote that you transcribed.

MS: Yeah. Also Karen Shakerdge and Eloise Lynton produced it and they came up with almost all of those archival bits. And some of them were really remarkably great. A few of them I knew of, I had existed through some of those things. But they really found some great stuff. And it really I think puts it onto a whole different level of understanding.

CR: Yeah, the Larry Kramer stuff was fantastic. I could go on forever, I mean I’m an audiophile, obviously, and I lived through the AIDS epidemic, but I didn't hear Larry Kramer, I didn't hear those ACT UP protests.

MS: Sometimes I wish I didn't hear Larry because he spent a lot of time screaming at me, though I ended up caring deeply for him, as did Fauci. And I actually dedicated this audiobook to his memory, because I think he had a really big impact on me. We went through periods as with everyone, with Larry, we went through periods when we didn't speak to each other and probably would have wanted to shoot each other. But we also understood each other and cared for each other and were important to each other. He lived to be 84 and I'm glad he did. I wish he was alive today. I wish he had been alive to listen to this project.

CR: It was sweet that you dedicated it to him. It says a lot for your relationship.

MS: It was hard to read some of those parts, just emotionally hard. Again, I've been interviewed on the radio a lot, but I've never done anything like this before. So I had my producer and executive producer, Brendan, and they were, you've got to do it again. It doesn't sound right.

And I would sit here doing it again and again and it was worth it, but it wasn't always the easiest thing to do. It's a medium that I think writers might take for granted. I think a lot of people think [with an] audiobook, you just write your book and then you read your book. But this wasn't like that at all.

CR: I'm glad. This is a perfect segue because I wanted to dig into that a bit with you, particularly writing and then the art of narrating, speaking out loud what you've said. But tell me about making that transition and what you learned maybe about your craft, making that move from writing for the page, then for the ear?

MS: Well, it was interesting, because what you need to learn to do is to write into the sound and out of it. So if you're going to be discussing an episode on the bird flu pandemic—it was a pandemic technically, but luckily it didn't infect that many people—we're going to have some clips about that. So you need to write the things you're writing, but you need to focus it. Sometimes you need to break it up a bit. Lots of times I would introduce someone then I would play a bit of a clip and then I would go back to them.

And when I say "I," I really mean Julia [Barton], because she has like magic ears. And she would say, you got to introduce her but you really have to do this, then you go back to her. It's just things you wouldn't do in writing, it would not seem consistent but the opposite is true in a vocal product like this one. It was really interesting to learn how to do that.

I'm not saying I'm an expert, but you do get the sense that you need to work your way into sound and out of sound and around sound. This is a fascinating learning experience for me.

CR: On the topic of the vaccines…how are you feeling and how has Dr. Fauci responded to this work? Has he heard it?

MS: Yeah, he just thanked me for it. I don't want to speak for him but I think we feel similarly about two things. One is, the way this epidemic has been handled on a federal level is appalling and shameful. And that is why so many people have died and so many are sick and why we're going to have such a terrible winter ahead. And it should not have been the case. But the other thing that I think we both feel, and again, I'm reluctant to speak for him, but I know he feels this way is, these vaccines are more than good news. One had hoped for maybe a 70 percent effective vaccine.

But the more important thing is that these vaccines are proteins. They're made in the lab, they're made to stimulate your antibodies. And this changes the entire approach to vaccination that has existed ever since Edward Jenner developed the smallpox vaccine by basically giving a dairymaid a cowpox shot, which is… For hundreds of years, we were basically throwing spaghetti at the wall and hoped it sticked. Our flu vaccines are grown in chicken eggs. They have been for the last 40 years. And what we really need to do is make vaccines with the engineering ability we have with biology now. Biology is becoming digital, and by that I mean you can manipulate cells and make parts of cells. And we can now make parts of cells that will protect us from various things. That's what's happening here. The fastest vaccine that has ever been developed was four years, I believe, that was a pertussis vaccine. This is a year.

So it's a big deal. And part of it is, science moves on and people are smarter and there was a lot of money and dedication. But part of it is that this system is an easier modular system, sort of the same way that you'd put Legos together or you'd put computer parts together, you should be able to assemble these things in a sort of standard way.

"One of the people I talked to about him said, "We'll know Fauci is retired when somebody goes into his office one day and he no longer moves.""

It's going to take quite a while to distribute the vaccines. There's 325 million people in this country, it's a two-dose vaccine, it's complicated. But it will start and it will end and we'll have defeated it. And it will have, in the end, been a scientific triumph. The amount of people who have and will die should be 10 percent of what happened. But we can't go back in time, we can't undo what other people did, but we can at least look forward to something better.

CR: And until then we wear a mask.

MS: Yes, we wear masks, we wash our hands, we do all the things that... They're not magic but they work.

CR: In hearing you talk, how you interviewed Fauci as part of The New Yorker Festival and this book itself, audiobook, audio piece, is just called Fauci. You think of people who you know by just one name and they are celebrities, Madonna, Prince, there's probably a less dated reference. But is he aware that he is a celebrity and does he like it?

MS: When Brad Pitt played him on Saturday Night Live, Tony's not an idiot, that gave him a bit of a clue. Yeah, he's aware now. I did write in some draft, either for The New Yorker or for this book, it got taken out either by me or by smarter people, that he was a one-name guy like Madonna. He is, there're not that many people that you can say just a name and people will know who it is. I think he likes being a celebrity to some degree. I think people enjoy the ego gratification.

You don't become an infectious disease specialist, if that's your main goal in life. But you also don't stay in a job through six administrations and do all the stuff he does if it bothers you. There's a thing in the book where we have a quote from him in the '90s basically saying, somebody interviewed him, it wasn't me, it was someone from the NIH saying, "God! You were vilified and hated and it was scary during the AIDS epidemic." And he said, "Oh yeah, well, it was never like physical threats and thankfully that's over now and we don't have to worry about that anymore." And that was nothing, he has said that to me, it was nothing compared to what he's going through now.

So I think that has been difficult and shocking. He's also gotten a lot of support. I bought my Tony Fauci bobblehead. The Fauci baseball card, despite his initial throw, sold out in a day. People respect him and they admire him.

CR: I have a final two questions. What's next for you? Are you going to keep writing about Dr. Fauci? And also what is next for Dr. Fauci, the subject that we're talking about?

MS: I am doing a couple things for The New Yorker, just sort of long-term things about public health. I have another project for Audible that we're not able to talk about it yet. I mean not Audible, oh my god! Hopefully it'll be on Audible, but it's Pushkin.

CR: Lowercase a, it will be audible, right?

MS: It'll be audible. I think that will be an exciting project. I also teach, I'm not going to teach this winter but I like teaching because college students, sometimes you want to kill them, but they're mostly very engaged and they care and they want to learn things, and they're not afraid to be challenged… So it's been fun to do all those things. As to Fauci, frankly, he [turned 80 December 24], I wished that guy would… He's not going to retire. He's not going to just like go fishing for the rest of his life.

One of the people, I think it appeared in the audiobook, I can't remember, but one of the people I talked to about him said, "We'll know Fauci is retired when somebody goes into his office one day and he no longer moves." To some degree there's some truth to that. I know he'll want to sort of oversee the distribution of the vaccine. And once that's done a year from now…I hope he'll consider lightening it up a bit, just from a human point of view, I think that would be good for him.

CR: He's earned it. This has been great. And I'm thrilled to hear that you've been converted to being an audio geek.

MS: Totally.

CR: And I look forward to what's next.

MS: Thank you so much and thanks for doing this.