Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

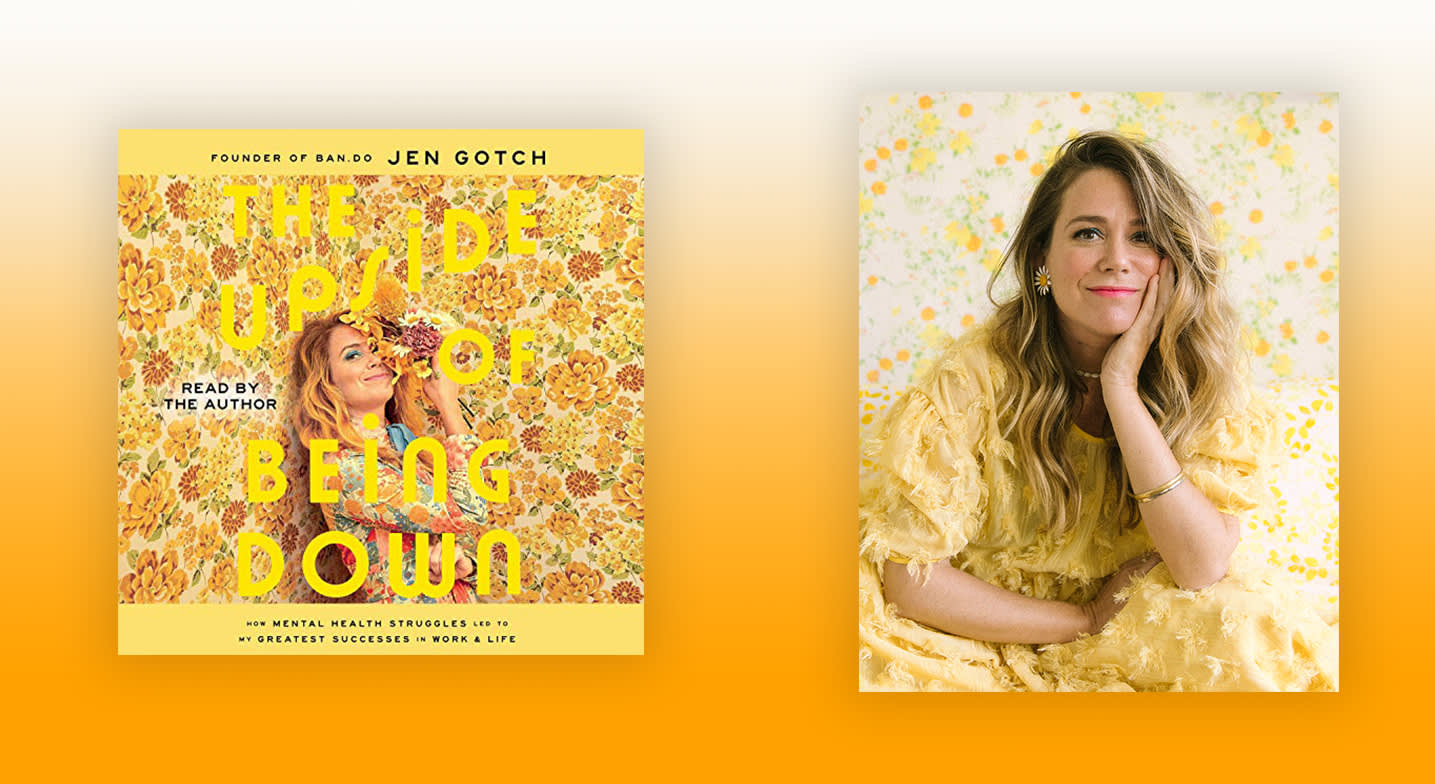

Rachel Smalter Hall: I'm Audible editor Rachel Smalter Hall. Today I'm here with Jen Gotch who's the founder and chief creative officer of the lifestyle company Ban.do, passionate mental health advocate, and lover of bold prints and glitter. She's also the author of The Upside of Being Down, her new memoir about how her struggles with mental health led to her greatest successes in work and life. Welcome, Jen.

Jen Gotch: Thank you. I'm very excited to be doing this.

RSH: It's exciting to be talking to you. I actually fell in love with your memoir before I even dove into it. I loved it from the second I saw the cover which I think was a universal experience on our editors team. I'm dying to know, did you get to have any input on styling the shoot?

JG: I think the level of input that I have, I was told, very uncommon for an author. So yes, I did. They actually let me produce a creative brief for the cover, recommend the photographer and the rest of the team that worked on it, recommend the designer who did the graphic text over the photo. So I was incredibly grateful to be able to do that, obviously, because... well, not obviously but within my job at Ban.do I've been selling book covers essentially for many years. Selling the book is going to be another question. But if I can make a great cover, I've done that before. So let's start there and the team at gallery has been incredibly supportive in me going outside the normal lines of what an author would do.

RSH: You know, I asked the question because I was so fascinated by your stories early in your career styling photo shoots and I was like, "Oh my god, this cover's amazing. I bet she had a hand in it." But I hadn't made that connection between the work that you actually do at Ban.do and now I know why we emotionally resonated with this cover before we even opened it. That's amazing!

JG: Here's what I will say. I didn't want a picture of me on the cover. I actually suggested a cover that was just the title that looked sort of like a '70s, '80s self-help book. And everyone was like, "No, it's a memoir. Your face is going on the cover." I was like, "Okay. Well, then we'll put text over it."

RSH: Nice. And some flowers. So I feel like for the benefit of our listeners, it's kind of unfair that they're not looking at the cover right now. Can you describe it?

JG: Sure. It is a picture of me actually in a bathroom, which you can't tell. But it's a room that is just wall to wall vintage, yellow, floral wall paper and then I am in a vintage sort of blue and pink floral dress, holding flowers. So it was sort of a flower-on-flower-on-flower and I talk a lot about having yellow as my power color. So the fact that there was this yellow bathroom and then we were able to lay the tile and yellow text over the image felt very true to my aesthetic and what I stand for. Hopefully it evokes joy in people just looking at the cover. Which it sounds like maybe I got there.

RSH: I think maybe you're onto something. It's almost like you do this for a living.

JG: I know. [Laughter]

RSH: So let's talk about what happens once you dive in past the cover. You are so open about your mental health in this book. I think it was within the first five minutes, you talk about having bipolar disorder, anxiety, and ADD. So I really want to know what inspired you to share that part of yourself with the world?

JG: For some reason, I have never had the filter to not share those types of things. And it wasn't really something that I saw necessarily as an advantage for a long time. But then obviously when social media became popular and over time I began talking about the struggles that I was having, the way it empowered other people and resonated with them and helped them feel less alone was enough for me to know that... I mean, it's strange to call it a gift but I do think in ways it is a gift because people always ask me like, "How are you doing that? Isn't it scary? Don't you feel vulnerable?" And I don't. So to me I don't feel brave because this feels very comfortable and also important as we try and destigmatize mental health issues. Talking about it is the best way to do that.

RSH: You had touched on so many things that I want to talk about just in that gorgeous, eloquent answer. Around the stigma with mental illness, I was dying to ask about this because I've seen it in employers who are scared to hire someone with a history of mental illness, and even really recently there was a situation where my own local moms group in Manhattan was discussing whether they would ever hire a caregiver who had been in therapy. And the fears around it, to me seemed so outlandish but to them those fears were really real. And I was wondering if you could talk about how pervasive you think this problem is with people being afraid of mental illness and where we need to go next to address it.

JG: Well, first of all, I would say absolutely hire a nanny that's been in therapy. That's probably the most self-aware nanny that you can find. But what I've realized the deeper that I've gotten into these issues and advocating for mental health awareness is I've never felt like a liability for someone. And I really didn't realize based on the type of workplace that I'm in that I obviously control a lot of what is normal, what is acceptable, what is encouraged. I understand now that that is different than what most people deal with.

And, again, I feel like it's just another way that my life experience set me up for success to be able to do what I'm doing. But I'm sure that part of the answer should be legislation and speaking at a high level in the government. Not at all how I approach it but thankfully there are lots of people that do it. That way, for me, continuing to talk about it in a way that resonates and makes sense that is lighthearted so that it doesn't feel like a burden but just a part of being alive and I think, more than anything, it's something that I wanted to do with the book is just show the interplay between mental health issues and success.

And that you can thrive so that it doesn't have to be this debilitating thing that brings up all the questions that you just said your group was asking or that an employer would have to understand that you can have both and not just me. And people say that to me a lot. I don't know if it's a compliment or not but they're like, "If you could do it, I could do it." And so I'm like, "Good. I'm glad you feel that way." That's how I want you to feel.

RSH: So I love how you talk about your mental health issues as a strength. You admit that they're kind of a pain in the ass sometimes but they're also a strength. I love this quote. "After years of working with Laurel and nurturing my own increasing interest in mental health, I had developed a good amount of emotional intelligence. This ability to recognize my own emotions and also have empathy for others and able me to innately understand what would resonate with customers. I could sense it almost viscerally and it seemed that my sensitivity and struggles pointed us in the right direction." So, Jen, can you share a little bit more about how, especially at work, you've been able to harness your brain chemistry for good?

JG: Absolutely. Well, I think, like I said there, not just the emotional intelligence but also the empathy that comes along with that has just helped me pick up on things, I think, actually before there's something that is like other people are aware of so in my mind it has helped me, internally at the company, support the employees on a level that's probably a little bit deeper than most founders would support their employees.

But also to be sensitive to our customer and our community and just understand. We do so much with phrases and I think when I looked back I was like, "Oh, I can see that I'm trying to evoke joy in people," because I know how important joy can be and that it's an emotion that lives inside of us and sometimes it just needs to be evoked by someone else. Whether it be [through] a color, a pattern, or a phrase. And so I feel like these were all things that I was sort of doing for myself and not realizing it. And then starting to put it out there and have it resonate, to me, is just directly due to... if I wasn't struggling and I didn't go to therapy and I didn't have these lows and these highs and these anxieties, the depth of how I feel would be different and I don't feel like I would be able to access those things.

RSH: I really connected with this idea you had about the crying rooms. This is an awesome idea that you put in the book. You say there should be crying rooms in offices and public spaces that are like these cozy rooms where people can just go emote when they need to. And I made a note to myself to ask you this because you say, "That by the time this book is published, mark my words, Ban.do will have a crying room." Did you do it?

JG: Here's the thing that I want to tell you about that quote, which I was reading last night because one of my friends called me and was like reading passages of my book to me. Actually Kim Ferrier, the owner of Ban.do, she's just like, "I love this book." And she was reading the passage and I was like, "Oh, no. The crying room." So I think this is a great example of how someone who is seemingly in charge of everything at a company cannot get what they want in the timing that they want it. I was like, "I mean, I will build this myself." And we have this open floor plan office so there are not that many rooms.

And our HR director was like, "I really need an office." The room I wanted to be the crying room because it's the only room that isn't glass, she was like, "I need it." And I was like, "Well, I agree. So can we make it a place where people can cry and have a comfy couch and candles?" And she's like, "Absolutely. That's part of my job anyways." So no, I failed. There is no crying room yet. We will continue to use my office, the bathroom, and now the HR office until I'm able to just get this thing done. I won't give up until it's done, by the way.

RSH: I feel like that's another aspect of you harnessing your brain chemistry. You're going to get it done. I love that tenacity that you have.

JG: It's about not being deterred or disheartened. To just know, "Okay, well... " I don't know. For me it's things don't always happen in the way that you had hoped and the timing you had hoped but that doesn't mean it can't happen. It just means readdress it, find another angle. I also think it's a really good lesson in that there is not one person that has ultimate power even though things are portrayed that way. I was like, "Well, this will be interesting for people to see that I couldn't do it. Because I have to run certain ideas by people and there's accountability.” So, anyways.

RSH: From one open office to another, I completely understand the competitiveness for meeting room. But I wish that it would happen at some point.

JG: I think it will.

RSH: That's great. And thank you for being so honest. You could have just lied and told me but you're so honest.

JG: No, oh my gosh. That's not in my DNA.

RSH: Right. And so I want to dig into that honesty. You have such candor about your family. It was so refreshing. You talk a lot about the financial support you had from your parents throughout your 20s. And this is when you were really struggling with your mental health, you didn't have an accurate diagnosis, you were on incorrect medication. Can you speak to what that support meant along your mental health journey? And I understand that it wasn't always a positive thing even though it definitely was sometimes. Could you speak to that?

JG: Yes, certainly. Yes, well my journey probably wouldn't have occurred, at least in the timing and the manner that it did without that financial support. And I also know that that, even though that was, at the depth of my struggles, was such a luxury to be able to have parents that felt accountable enough for part of it and cared about me enough that they made the sacrifice to support me at a time where it was just really many times hard for me to get out of bed for months. So, I mean, in a way I was feeling very disabled and I didn't have the skills to do that. So I don't know. I guess I just want to acknowledge how fortunate I was.

I think the downside is kind of, A, knowing you have a fall back from a career standpoint I certainly wasn't as motivated as I could have been. And then also, when your parents are financially supporting you in that way, you're a grown up that has to report back to their parents and do what they say or else you don't get the money. So at times, that felt like it was both empowering and also took away a lot of my power. But, again, I don't look back at anything and think, "I wish it were different," because I like where I am and I know I needed to have all of those things in order to get there. But yeah, wow, I haven't thought about that in a while.

RSH: The thing that really stuck out to me is that it doesn't matter who you are, where you come from, mental illness can still affect you even if you come from this family that has the means to support you. I mean, obviously it helps you in that journey in some ways but it just stood out to me that mental health and mental illness affects everyone.

JG: Of course.

RSH: Yeah. To pivot a little bit, I feel like I've seen this trend of fashion intersecting with wellness. So I'm thinking of Elaine Welteroth of Teen Vogue and Project Runway, she wrote this fantastic self-development memoir. And then there's Morgan Yakus, the founder of Number 6, who left to become a hypnosis practitioner. What do you think that might be about?

JG: I can speculate. I don't feel like I'm in necessarily in the fashion industry. We're a lifestyle company so we certainly dabble in that but I think any business where you're sort of serving a customer and using your own emotions to contribute to your creativity which eventually ends up with a customer. I think it's similar to what I was saying earlier, you get a better view of people because you get so much feedback and you see what's working and you're just connected into this consciousness that I feel like is part of your job.

But it also allows you to see these other things and then you also realize that you... at least for me, I started to realize how much access I had to that. I feel like once you start to recognize that, you almost feel like your purpose should be to do more but like I don't know that it necessarily always be walking away from what you're doing. But I think just knowing that what if you fold that in when you already have the attention of these people and the trust of your customer and your community, what are the limits to the things you could help them with or expose them to or share with them.

And the other part of that is wellness is a huge trend right now. And I feel like any fashion company certainly is about following trends and I think, again, the whole point of a trend is that it’s resonating with a large group of people, so why not fold that in. I mean, I think for us it came to fruition quite differently but we have people's attention around that in a way that we didn't before, even though we've always been talking about that. It's just wasn't on their radar like it is now so. This is all me speculating. I don't know.

RSH: Once again, Jen Gotch, the trend forecaster. I love it.

JG: Listen, admittedly I do think it is a skill of mine. I also live in Los Angeles so we... I mean, it's the same as New York. It's like in the air.

RSH: Right. No, but actually I did not know the very early history of Ban.do, and it kind of blew my mind the story about the flower halo. I think that's what you call it in the book. I remember the “flower crown” moment. And so I was totally fascinated that you were plugged into that before it was even a thing. And that's really the origin story of Ban.do.

JG: Totally, it's an interesting thing plugging in in that way. And sometimes it serves you and sometimes it doesn't. I feel like when you're far ahead of what the majority of the population is wanting to consume or where, there is this period where you're like, "Can anyone see me?" I mean, I think it was a similar thing with mental health stuff. When people started to recognize that that was a thing for me, in my mind I was like, "Well, I had been talking about this publicly for years."

It just wasn't grabbing the attention like it does now. I feel like it's a similar thing where being ahead like that sometimes means, unless you're in the high, high fashion where people are waiting for that, you're sort of speaking into a vacuum for a while. Which was just something I had to understand and get used to, to know that it's not necessarily that it's not the right thing or not the right idea but it's just the timing may be off. But that's sort of your job. Just lean into it and wait. I understand that now. It took me a long time to get there.

RSH: Yeah, so speaking of reflection. I want to close with a question about the process of writing this. In the very beginning you talk about how you did go into the space of asking yourself from really tough questions while writing the memoir and that at points doing it the difficulty pushed you to some low places of frustration and self-doubt but then on the other side, you say you've felt stronger than you have in years. So my question is a little bit about that but it's also about narrating. So you got into a studio and read this story into a microphone. Did that experience bring up any different feelings than writing it did?

JG: I, first of all let me just say, was equally excited and terrified to narrate my book because I haven't really read aloud in front of other people since I was probably in high school. And I thought well, "I can read inside my head and I know I can read aloud." But what is that going to be like? So I actually think, first, you spend several days going it and the guys that I was working with were just incredible and so supportive but I think at first it was like... it took me a minute to connect to the words because I wanted so badly to just do a good job and let the listener feel like they are hearing my story from me.

And so I wanted to have the right inflection and tone and make sure that the jokes are funny. So reading it then, as I started to really hear what I was saying and absorb it, was strange in that you're sort of outside yourself in a different way than writing it. Even when you go back and read what you wrote. To have it read out and then also can see in another room, people reacting to it, it gave me sort of a distance from it. So it wasn't as much that it was evoking things, it was like let me examine it in a different way. And when I was done I was like, "There's a lot of information in this book." I was like, "Is this multiple books in one?"

And it's funny because the guys were two like 40-something guys and were like, "This is amazing. It was like being in therapy." And I was like, "Wonderful. That's what I wanted." But I think as a narrator and as an author, you experience it in a way that you haven't. So it was very fulfilling for me more than anything else. I figured I would be crying a lot but that didn't really happen that much.

RSH: Maybe you had already experienced all the emotions while writing it. I think that's definitely possible.

JG: Yeah. And reading it. Even just when I actually sat down to read it. Once we had the galleys, I mean, I cried a lot. But not because I was sad, just as an emotion that covers a range of feelings. But, I have to say I'm so incredibly grateful that I was able to narrate it and it turns out I can read aloud into a microphone. I do feel like it makes the difference between having someone who isn't as connected to the material do it. So hopefully that'll come through.

RSH: Jen, thank you so much for talking with me today.

JG: Of course.