Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

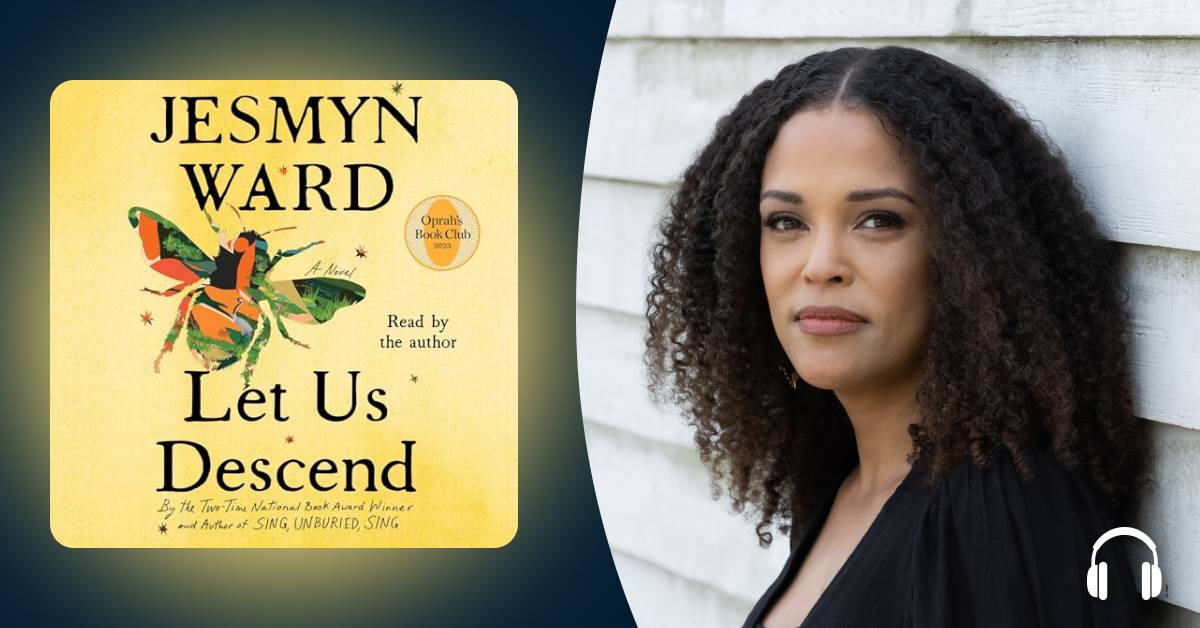

Tricia Ford: Hi, listeners. I'm Tricia Ford, fiction editor here at Audible, and today I'm thrilled to have the opportunity to speak with Jesmyn Ward, who you'll know from both of her National Book Award-winning novels, Salvage the Bones and Sing, Unburied, Sing. She's here today to talk about her latest novel, Let Us Descend. Welcome, Jesmyn. Thanks so much for being here.

Jesmyn Ward: Oh, it's good to be here. Thank you.

TF: Let Us Descend, in short, it's the story of a girl named Annis, a young enslaved woman who's separated from her mother, sold to the Southern man, and forced into a descent from the Carolina rice fields to the New Orleans slave markets and into a brutal existence on a Louisiana sugar plantation. Along the way, Annis uncovers a hidden world where spiritual forces and African ancestor wisdom help her survive the inhumanity she endures.

So, it's such a beautiful novel. But where I want to start is with the heart, which is Annis herself. This woman is so richly developed, and it's in ways a historical novel, which I think to some people kind of charts a timeline. But this is an internal journey. So much an internal journey. And she's someone that you really feel like you know. So, I was curious, is she inspired by any real-life people from history?

JW: Not really. I mean, as soon as I sort of found or stumbled upon the idea for the novel, Annis appeared to me. I didn't know anything about her, but as soon as I thought maybe I should write a novel about someone who is going through the slave pens of New Orleans, she popped into my head. I thought, "Oh, it's a woman." And it's specifically a young woman. She was a young woman from the very beginning. And then, once I began to research, I sort of learned more, I guess, about the world that she lived in, and some of the things that she might have experienced in that world, and how that world might have informed who she was and her way of thinking and her way of, I guess, trying to survive that world. But she wasn't really inspired by one particular person.

TF: To me, Annis could be a woman you meet today, which kind of brings me to the audio and your performance. You chose to narrate yourself, and quite honestly, you probably could've had your pick of actors to do this for you. What led you to that decision? Because your voice is now Annis.

JW: [Laughs]. I don't know. I haven't had to answer that question yet. I worked for a really long time on this book, you know? This book took me around eight years to write, and that's from conceiving the idea and Annis appearing to me, researching for two and a half years, and then writing. Writing the rough draft and then revising. All of that together took around eight years.

During that time, there were other writing assignments that I did that were born sort of out of that world that I was inhabiting, because I was writing Annis's story. So, one was my entry for the 1619 Project. That was written from that space. And I actually read that essay I think for their podcast. And when I was reading it, I got emotional near the end. Like, I started sort of tearing up at the end and feeling a great sense of part-sadness, part-triumph in the telling. I mean, it's very complicated emotions that I was feeling all at once, and I started to tear up a little bit. And that doesn't always happen to me when I'm reading something, because I do events all the time. I read all the time. But having that kind of very complicated emotional response, that doesn't normally happen. And so I took note of that.

"It felt important to me to read this one specifically...I think there's just some sort of emotional connection that I felt here that I wanted to try to communicate in the reading of the audiobook."

And then I was invited to take part in the Toni Morrison memorial in New York City years ago. And what I wrote for that, there were also hints, I think, of Annis's world and of all the things that I had learned or was learning in the writing of that world. There were hints of that in that piece. And again, I felt that same sort of emotion, that sense of multiple complicated emotions welling up inside of me. And so I feel like I wanted to attempt to narrate this. Because I was nervous about it. I have never done it before. I try to be a good reader when I'm doing events at bookstores and stuff. But I'm definitely not a professional. There was something about reading this book that, I don't know, that I felt very connected to it. And it stirred something in me. And it felt important to me to read this one specifically. I think the only other book that I felt this way about is probably my memoir, Men We Reaped, which I didn't read, but part of me wanted to read. So, yeah, I think there's just some sort of emotional connection that I felt here that I wanted to try to communicate in the reading of the audiobook.

TF: Yeah. From my perspective as a listener, I definitely picked up on that. It's hard to explain. But it was a raw performance, in a way. Not to say it wasn't refined, because it was extremely refined. But I just love the voice you gave Annis, because she just seemed like a woman standing next to me, not someone out of history, but someone just alive and with me. So, I loved your performance.

JW: Thank you. I mean, that was part of what I was trying to do in the writing of the book. It was something that I was thinking about the entire time, before I even put one word down. I was thinking about Annis and thinking about who she was and how she would be trying to survive this moment. But not only survive, because she's struggling with grief throughout, like multiple griefs, multiple losses. And one of the things that the book is about is this person who is trying to create a new reality. Which I think is like the hardest part of grief, right? Because you're trying to find a way to a new reality, because the reality and the present that you thought that you would have with this person who you loved and lost, that life doesn't exist anymore. And so part of the work of grief is trying to work your way towards finding a new reality and a new present and a new way of living, where you still carry that loss, but you learn to live with it.

She's constantly doing that in the book, and I think that understanding that emotion, that grief, and that that was one of the bigger things that she was struggling with throughout her journey, that helped me to really access her as a person and sit with her as a person and immerse myself in her experience as a person. And I think people often have knee-jerk reactions to narratives about enslaved people. It's such a difficult subject that I think people resist engaging with it. But I think we do that to our detriment, because we don't engage with it, and so, therefore, it's easy for us to flatten enslaved people in our heads. And to not see them as complex, complicated, textured people. And so that's something that I really wanted to try to do just as well as I could with Let Us Descend. Really immerse the reader with Annis into this world and reveal that she's just a person who is trying to do what she can with what she's been given, you know? She's trying to not only survive what she's experiencing, but also work her way to a place where perhaps she can thrive.

TF: Right. And that grief, the primary grief, I guess you could say, in the book is the loss of her mother. And their connection is just a fierce force within this entire novel. And one thing that I would love to play for everyone is from the very beginning of the book. It gives everyone a taste of your voice as Annis, and of this fierceness that Annis and her mother share. You'll know this part. Chapter one.

Audio from Let Us Descend: The first weapon I ever held was my mother's hand. I was a small child then, soft at the belly. On that night, my mother woke me and led me out to the Carolina woods, deep, deep into the murmuring trees, black with the sun's leaving. The bones in her fingers, blades in sheathes, but I did not know this yet.

TF: That I think is going to become one of those lines in literature that people will know when they hear it, where it came from. It's so beautiful.

JW: Thank you.

TF: And just that little sample of your voice. What is your perspective on their relationship? There's so much affection. But there's more than affection. There's that practical thing going on here as well. Can you talk about their relationship a little bit?

JW: Yeah. I mean, Annis's mother loves Annis very much. I think that both she and Annis are aware that they can be taken from each other at any time. And so I think that does inform their relationship. The fact that they both have this awareness. In what I wrote, they never had a conversation about it. And I don't know if they ever would've had a conversation about it. But the understanding was there, right? And I think that that understanding meant that they cherished each other more, because they knew that at any time they could be split and could be separated from each other.

Annis's mom, I think, also feels a responsibility to equip Annis with what she thinks that she's going to need to survive and to make her way in the world once the mother is gone. And whether that's because they've been split apart or because they could've gotten really lucky and the mother could've died in old age, but her mother is trying to prepare Annis for the realities of the world. And so part of what she does in order to prepare her for the realities of the world is she teaches her how to fight. And this is something that Annis's grandmother passed down to Annis's mother, because Annis's grandmother was a woman warrior, and then she was captured and sold and took the voyage across the Atlantic and ended up in a Carolina rice plantation. But she brought that knowledge with her, that knowledge of how to fight, how to defend yourself.

"I think people often have knee-jerk reactions to narratives about enslaved people. It's such a difficult subject that I think people resist engaging with it. But I think we do that to our detriment."

And so she passes that on to Annis's mother and Annis's mother passes that on to Annis, but it's complicated, because Annis can't necessarily use it, right? And I think that's one of the things that frustrates Annis early on in the novel. She's like, "You're teaching me these things and I can't really use them to defend myself against the people that I need to defend myself against." But her mother basically says, "This is not only just about me teaching you how to defend yourself, but this is also a way that we can retain a sense of self and a sense of family and a sense of people and of who we are outside of this inhumane system. I passed this down to you. I tell you story after story after story of your grandmother or of my life.” Because her mom's a real storyteller, right? Her mother also teaches her how to forage and how to collect mushrooms and herbs. All this knowledge and history that her mother passes down to her to do that, to sort of retain a sense of their history and a sense of their self. And so they have something that no one can take away. The mom says, "These are the things that no one can take away from you."

TF: And there is a foreboding in the beauty of this mother-daughter bonding, of “she's going to need this going forward.” It's not for naught that these skills are something she will need.

Which, this takes me to, once her mother is taken away, it's not long before Annis goes on her own journey South. This is kind of where the parallel between Dante's Inferno really picks up for me. One of the parallels between the Inferno and Let Us Descend is how Annis is accompanied on her walk by Aza. So, Aza came in, and Dante—we all know Dante was led through from Virgil—so Aza is kind of like Annis's Virgil. So, I was curious, how similar are they, Aza and Virgil? And one thing I'm super curious about with Aza is, not to make it too simple, but she's kind of mean. Is she a comfort or is she a threat? Or is she both? I would love to hear what you think about Aza.

JW: I think that she's both, and I think that she's more. I think she is like Virgil in that she's a god, right? Something of a god as she accompanies Annis on this descent, this walk South. But for me, she was very different in most other ways. She's very different. Because she is mean, right? Because she's very self-centered. Because she wants to be worshiped. Because she wants to be regarded. Because, I think, that she wants to be loved. But not like a supplicant loves a god or goddess. I think more in the way that a child loves a caregiver. She has particular motivations. There are things that she wants. And I think that she thinks that she knows what's best for Annis every step of the way. Sometimes she has little regard for Annis and for what she's going through, what she's enduring. I think because it's so alien to the spirit's sense of the world and experience of the world. I feel like, in a way, she doesn't empathize with Annis and Annis's wounds and Annis's sorrow and Annis's very human longing, right? Annis's hunger for self-determination. That's all very alien to her. I think that comes out in her behavior.

When I thought about writing the fact that this world would contain multitudes of spirits, I did not want those spirits to be either/or. I didn't want them to be either wholly evil or wholly benevolent, which I feel like is a very sort of Christian way of understanding spirit. You're either one or the other. I felt like in this world, in this time, in this place, that perhaps that world would be peopled by spirits who were more complicated than that. Who were as complex and as complicated as the human beings that they interacted with. With each of the spirits that found their way into that book and into that world, I tried to make each of them complicated and not fitting into one camp or another, either wholly good or wholly bad.

TF: It's almost as if you can plug into their power, and very literally with Aza—she's electric. What you do with it is kind of up to you, right?

JW: Right.

TF: That's kind of how I took it. But she scared me, too [laughs].

JW: Yeah, she should [laughs].

TF: In a good way, I guess. But yeah, she's incredible. She's a power, to say the least. It's perfect for a novel, just the many descriptions of her. Like, you see her. But I would love to see a physical representation of her too. That would be beautiful, if someone made a painting or a film or something like that. That would be amazing

JW: It would be amazing. I mean, she's a storm spirit. I think it would be really interesting to see her on film. The ways that visually you can interpret her being a storm spirit. Yeah, I totally agree.

TF: Now, one thing that we talked about a little bit, that I feel there are lessons here about grief. It is so central to the story, and Annis's journey is kind of like a journey into the depths of grief. But she does come out of that. Do you feel like there's lessons in her journey and how she deals with things that anyone dealing with grief could learn from?

JW: Definitely. I've lost a lot of people that I love in my life, and when I was writing Let Us Descend, in the middle of that process, my partner, the father of my children, he died unexpectedly. Before he transitioned, I was struggling with Let Us Descend. I had written my way around three chapters in, and I stalled out. And so when my partner died suddenly, I just wasn't writing at all. I wasn't even forcing out a paragraph a day or a section a day. I was writing nothing. And this lasted for around six months, where I just didn't write anything, which is really strange for me, because I am very disciplined about writing. Five days a week, at least two hours a day—I have dedicated to writing on that schedule for years, and I wasn't.

"[Annis's] journey helped me to realize... that even when life is difficult, it is worth living, right? And that there's always hope at the heart of it that you can live your way to a better tomorrow. And that part of the way that you find your way to that tomorrow is through connection, is through community."

I realized that I was at this moment where I felt like giving up, you know? Where I felt like I had given up, because I felt really hopeless and I was really mired in my grief. And this feeling that nothing would ever get better. Just a real sense of hopelessness, which I have felt before, twice. Once was after Hurricane Katrina, and the first time was when my brother died, when he was 19 and I was like 23. And so I'd been at that place before. The first time that I was at that place, with my brother, it actually made me write, because I came to this realization where I asked myself, "Okay, what am I going to do with this life that my brother was not given, that my brother did not have? What am I going to do with this that will make this worthwhile?"

And the answer that came to my head was writing. And then after Hurricane Katrina, I almost stopped writing. I had been writing for, I don't know, eight years or something at that point. And I almost stopped writing. And then that intuitive voice spoke up again and was like, "No, just keep trying. Just try one more time. Send your manuscript, your novel manuscript, out to one more publishing company." And that was it. That was when my manuscript was picked up and I got an offer for my book to be published.

And so then this time, as I'm sitting here and I'm thinking, "Okay, maybe I've written the last book that I'm ever going to write," that voice spoke up again. And that voice said, "The last thing that B,"—because his name's Brandon, but I called him B, his nickname was B—"The last thing that B would want is for his leaving or his loss to silence you.” And so I said, "Okay," and then I dove back into writing Let Us Descend.

I was only like three chapters in, and so I wrote forward as if the first three chapters were good, which they weren't [laughs]. But I found that when I went back in and began writing, that I was able to write with a new awareness of who Annis was and of what she was living with, and what she was struggling with. Because suddenly she became more than a person who doesn't have any physical agency, right? Because that's what I think that we think of whenever we think of an enslaved person, we think, "Oh, this person just had no agency." And it's such a big thing to get over that. I feel like it's hard for us to relate to them. But when I went back into Let Us Descend and I realized just as I was struggling with my grief and my loss and missing this person who I had hoped and thought would always be a part of my physical, present life, and they weren't, that's the same thing that Annis would be struggling with as she is separated from her mom. She's sold away from her mom. But then, here she has not only that grief to contend with, but then she has these other losses along the way as she makes connections with people and then as she loses them.

I mean, because she's always sort of reaching out and making connections with people, forming friendships, forming relationships, finding family along the way, which I think is a testament to how she didn't give up, to how she was doing the hard work of not only existing in that world, but also reaching out even in the midst of her grief and still risking and reaching out and trying to make connections with each other. Her journey helped me to realize—I do think that both of us realized it at the same time—that even when life is difficult, that it is worth living, right? And that there's always hope at the heart of it that you can live your way to a better tomorrow. And that part of the way that you find your way to that tomorrow is through connection, is through community, is through family, is through friends, is through relationships. Making yourself vulnerable in the living. Yeah.

TF: Wow. That all shines through in your epilogue. It kind of shines through in your own story. You thank so many people, and so warmly and personally. I feel like I know these people now. So, it's another connection, not only are you Annis's voice, there's a lot of parallels there.

JW: There is. There is.

TF: Which brings me to another question that I have for you. Who do you write for? Do you write for yourself or do you have a particular audience in mind when you write?

JW: I don't know. I think that I write for multiple audiences. I mean, yes, I do write for myself, because I love it, and I've always loved it. I'm engaging in something beautiful whenever I write, right? I'm doing something that feeds my soul whenever I write. But I do write for my family. I write for my extended family. I write for my community. I write for people who could be part of my extended family, who could be part of my community. I write for Southern people, Black people, poor people, people who are all of the above. I feel like I write for people who are marginalized in some way. Who come from marginalized communities and don't often see their lives reflected in popular culture and in literature that they consume.

But then I feel like I also write for anyone who has ever lost someone, for anyone who has ever struggled with grief. I write for that person, too. I write for children who are made to grow up too quickly and who are made to be adults too quickly. I write for young adults who feel bewildered in the world and who are trying to figure out how they're going to live their lives and what that even means.

So, I don't know. I feel like I write for all kinds of audiences. I remember the first time that that occurred to me, that I wrote for more people than I initially thought. Because when I first started writing, I thought, "Oh, I'm writing for me and my family, my community. I'm writing for this group of people here." But then after Salvage the Bones came out, I did a book festival in Australia and one in New Zealand. And when I was at the one in New Zealand, I met people who had been affected by the Christchurch earthquakes, and they came up to me and they were deeply affected by Salvage the Bones. And they said, "We love this book so much.” Because they saw some of their own experience sort of reflected in what Esch and the characters in Salvage the Bones went through with Hurricane Katrina and in the immediate aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

And I was like, "Oh, people don't have to look like me. They don't have to come from the same socioeconomic background that I do. They don't have to come from the same place in the world that I do, but they're still finding something that resonates with them in this world that I'm writing, and in these characters.” There's some kind of way that these characters become universal for readers, regardless of where they're coming from. And I think it's because so often, so many of my characters, they're just struggling with things that all people struggle with, right? They're struggling with loss. They're struggling with family relationships, with romantic relationships, with first love, with trying to weather natural disasters, with substance abuse. They're struggling with things that so many people in the world encounter. So, I hope that my work, in part, helps people to navigate those things.

"There's some kind of way that these characters become universal for readers, regardless of where they're coming from. And I think it's because so often, so many of my characters, they're just struggling with things that all people struggle with...So, I hope that my work, in part, helps people to navigate those things."

TF: I think it does. And it's that humanity that shines through these characters. As a fiction lover, it's all about the characters, and this one was amazing. Annis is such a focal point, and this is like a deep dive into a woman whose existence we aren't even allowed to imagine, and you allow us to imagine it, so thank you. It's beautiful.

JW: Well, thank you. Thank you.

TF: So, what are you working on now?

JW: [Laughs] At this very moment? Nothing, and I feel so guilty about it. Because I've been on book tour and it's really hard to write when you're traveling. I'm off, but now I'm off right in time for the holidays, right? So, I am going to be busy with that. But I am pretty determined to begin writing a new book come January. Because I'm actually under contract to write a middle grade slash YA book, which is something I've never done before but I've always secretly wanted to do, because I want to write the book that I was searching for when I was this little voracious reader in elementary school. So, that's my hope. I'm going to start working on that book in January and I'm very excited about it, but I'm also very nervous because I don't know what I'm doing and I've never done it before. I am preparing somewhat already. I'm reading some middle grade books, reading YA books. I've also had a couple conversations with Jason Reynolds when I've run into him [laughs]. I'm asking his advice.

TF: That's a good idea [laughs].

JW: Yeah, so that's what I'm doing next.

TF: That's great. And one thing I also always like to ask is, I know you're a narrator, but are you a listener? Do you like audiobooks, podcasts, anything like that?

JW: I am a listener. I love podcasts. I love audiobooks. I listen to everything from, like, this book recently that I listened to that I loved called The Human Cosmos, which is all about stars and space and how the awe that humans have felt through the centuries about space has, in some ways, shaped our humanity and shaped civilization. It's a fascinating book. I tend to listen to more nonfiction like that on Audible. Like, right now, I'm listening to a couple different books at the same time. I just listened to Surviving Death, which is all about death and the possibility that there's an afterlife. And it's by this journalist named Leslie Kean. And then before that, I listened to this incredible book called Black Ghost of Empire by a writer named Kris Manjapra. It's all about emancipation and different emancipations around the world and how emancipation wasn't as clean and as honest as we think it is, right? So, it's a history book.

I tend to listen to history, and also true crime, which is terrible. And then I do listen to fiction, but I can only listen to kids' fiction on Audible. I don't know what it is. I've tried to listen to adult fiction. And it's something about, I guess, the way that my brain processes fiction, but it's hard for me to focus. I can listen to an entire book about the most obscure—like, I'm listening to The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. I could listen to that, focus with no problem. But for whatever reason, I can't listen to fiction. It's so weird. And sort of disappointing to me that I can't listen to adult fiction. I have to read all of it. So yes, I love podcasts. I love audiobooks. I just tend to listen to a lot more nonfiction than fiction.

TF: Yeah, maybe try some genre fiction [laughs]. That might be a way in, like some detective story or something. As an expert, there is practice, but I do think for the way my brain works, just some advice, is I don't often just sit and listen.

JW: Got it.

TF: So, it's finding the right dual activity that's not too distracting but helps you focus. So sometimes it's driving for me, where I'm focused, but it's a little auto, so I can still pay attention. I know a lot of people do knitting, different repetitive-type things that take that part of your attention so you can sit still and still take in the story. But it's different for everyone.

JW: That makes sense. I hadn't thought about it like that. Maybe that's part of the reason why it's so difficult for me to focus, because I'm like concentrating so much on the language and the words. Like, I'm listening probably like a writer, which probably requires way too much brain power.

TF: That's interesting, yeah. Could be. Well, keep trying [laughs]. And there's nothing wrong with podcasts and true crime. It’s totally respectable.

JW: And history. I listen to history [laughs].

TF: And history. So, Jesmyn, it's been a pleasure talking with you today. Thank you so much for being here.

JW: Thank you. Thank you for having me.

TF: And listeners, Let Us Descend is available on Audible now.