Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

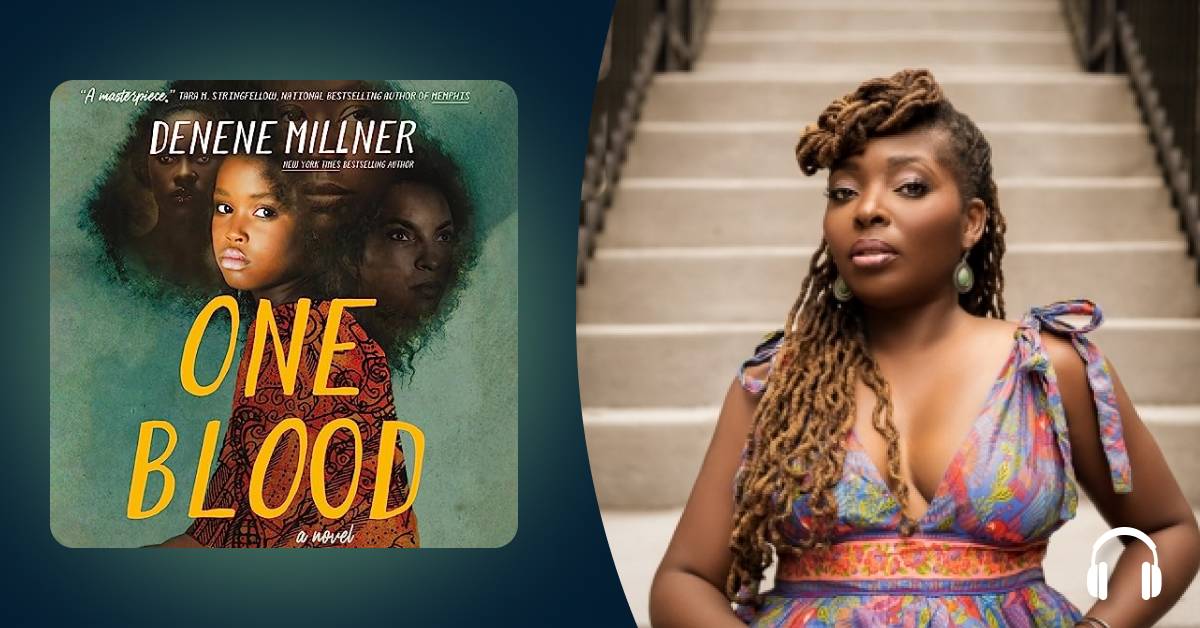

Margaret Hargrove: Hi, listeners, I'm Audible editor Margaret Hargrove, and I'm excited to be here today with New York Times bestselling author Denene Millner, who recently debuted her first solo novel, One Blood, an epic story about the connection between three women—a birth mother who has her child taken away, the adoptive mother who raises that child, and the woman that child becomes. This sprawling story spanning 60 years is a tender tale of Black motherhood, identity, and love, and boasts a fantastic multicast lineup of Bahni Turpin, Joniece Abbott-Pratt, and Queen Sugar's Tina Lifford. Denene, welcome to Audible.

Denene Millner: Thank you so much for having me.

MH: So, Denene, you've written or coauthored more than 30 books, including Steve Harvey's New York Times bestseller Act Like a Lady, Think Like a Man and Taraji P. Henson's memoir, Around the Way Girl. Given your already prolific writing career, how does it feel in this moment to release your debut solo novel?

DM: Oh, goodness. It's wild. It's exhilarating. It's scary, it … feels like a long time coming. I've always wanted to tell my own story, but I've been very cognizant of my need to make money and sustain myself and my daughters. And one of the best ways to do that was to write with other people or write for other people. So, the work that I did with Taraji and Steve Harvey, Jessye Norman and Charlie Wilson—books that I coauthored with other people that turned into the novel versions of films—all of that was in service to my background as a journalist and my job, basically. Not saying that One Blood isn't my job, but One Blood is way more my passion than it is my job.

MH: Great. Why tell this story now?

DM: I finally felt like I had something to say, and I had a lot of questions to ask of my characters. But really, the book was born literally on my 50th birthday. I was with a few of my best friends out in Tobago, and we were sitting on the deck … on a cliff overlooking the Caribbean Sea. And I had a notebook and a pen, and a little bourbon first thing in the morning (laughs) on my birthday. And I just felt like, now's the time to try and figure out what this book is going to be about and what the first sentences will be. And I wrote those first sentences.

That was in 2018. And then in 2020, during the pandemic when we were all locked down—Atlanta had just been locked down, and I had just moved into my new house. And George Floyd had just been killed, and then there was another brother here in Atlanta named Rayshard Brooks who was killed, not five minutes away from my house. And there were all different kinds of helicopters buzzing around and cops’ lights and sirens running all night. And it was a really scary proposition, because I had just moved into my new house, my young daughters were here—I call them young because they're significantly younger than me, but they were in their 20s. And it was the first time that I had lived in a house without the protection of a man. It was all on me. If anything happened, I had to protect my girls. And it was a scary, scary time. I wasn't sleeping. I found it hard to eat. I was worried about going to the grocery store because of COVID and worried about leaving the house because of the police presence and all that was going on.

And I told my agent, Victoria Sanders, how I was feeling about this, and she said, "Why don't you just write?" She said, "Just sit there and write. Just write something." And that's when I started writing, you know; I got serious about writing One Blood. And within a couple of weeks, I had the first 44 pages done. And then she read the first 44 pages, and she was like, "You need to go ahead and write me a letter explaining what this book is about. I'm selling it tomorrow. So I want that letter on my desk by tomorrow—by tomorrow morning when I wake up."

I wrote the letter explaining why I wrote the book, which really kind of put the icing or the topping on what it was that I intended with the book. And she sold it the next day. It went to my editor, Monique Patterson, exclusively on Thursday, and by Monday, I had a book deal.

MH: Wow.

DM: Yeah.

MH: It's a compelling story. You say in your author's note that you were 12 years old when you discovered your adoption certificate while you were kind of snooping through your parents' important papers. How did your own adoption story inspire One Blood?

DM: It inspired One Blood because as an adopted child, there's always questions about who your birth parents are, specifically your birth mother. Birth fathers don't really come into the conversation—it’s mostly the providence of the mother, right? Which is really kind of unfair, but that is the first bond. I was in her womb, and her blood is running through my veins, right? And so, as an adopted child, I always knew that she existed, but it wasn't until recently that I started questioning, like, what happened? You know, how did I come to be? What was it that... Was I made out of love? Was life too hard for her to care for me? Did somebody take me away from her?

And then I wanted to talk to my mom. I'll be 55 in a few weeks. And as I'm becoming more of a woman—and I say more of a woman like I didn't have 55 years to get here, but, you know, every year feels different—I'm not the same person that I was when I was 25, 35, even 45, even 50. And as I approach menopause, as I approach my daughters moving on and living their own lives as young adults able to take care of themselves—I'm single; I've been divorced for 6 years—and as I consider what relationships look like to me, I have so many questions for my mother, who passed away in 2002, three weeks after my second daughter was born.

"One Blood is really me asking questions of the characters that I wished that I could've asked of my birth mother, that I wished that I could've asked of my own mother, and then questions that I'm asking of my 34-year-old self."

I want to know why she lived the way that she lived, how she was in relationship with my father, how she was in relationship with her friends, how she was in relationship with herself. What was it that happened to her that she couldn't have children, and how did she come to the conclusion that she should have a baby through adoption? All of those things I wish that I could have asked her before she passed away. She passed away when I was 34. And I didn't think to ask those questions of her—one, because we didn't have that kind of relationship when I was growing up. She was very much mother, I was very much daughter, and adult issues were not to be discussed. I was a child, and I was to remain one until I wasn't anymore, right?

And then by the time I had my own kids, she was gone within three years of me becoming a mother. And in those first three years, it was a whirlwind. I was trying to figure out how to be a mother, and it didn't occur to me to ask her how she mothered when I was a baby. So it wasn't until after she passed away that I started thinking about that. And it wasn't until very recently that I started wanting the answers for real for real.

And so, One Blood is really me asking questions of the characters that I wished that I could've asked of my birth mother, that I wished that I could've asked of my own mother, and then questions that I'm asking of my 34-year-old self, from when I became a mom and I had a three-year-old and I lost my own mother and the things that I wished that I could've talked to her about, right? I won't give away the book, but there is, in the “Book of Rae,” a lot of answering those questions that I had from my mother, and in the “Book of Grace,” there's a lot of questions being answered that I had of my birth mother. So the answers are there for me. At least, some semblance of them.

MH: Let's talk more about the three women at the heart of One Blood. There's Grace, the birth mother, who has her newborn daughter taken away; Lolo, the adoptive mother; and Rae, that child who's now an adult with a daughter of her own. Did you have a favorite character among the three? Or is there any character that you identify with the most?

DM: I identify the most with Rae. She's the modern woman. She's a television producer. I was a young journalist in New York in the '90s, which is when Rae's story is set. So, that one was more personal because it just sort of tracks with the things that I was feeling and dealing with when I was her age with a relatively new kid ... living in Brooklyn. Those highlights—they very much track with my own story.

I have found it hard to like Lolo. I did. I found it hard to like Lolo because she was so hard, right? She lived a really hard life, and she was justified in the way that she interacted in the world as a mother and a wife and a friend and a woman in the different circumstances that she went through. But that didn't mean that I agreed with the way that she moved in the world. I just didn't like that there was very little softness to her. And that's the exact opposite of who I am as a mother and as a significant other, as a friend. I'm way more malleable and way softer than Lolo is, but I understand that circumstances of her life led her to be who she ultimately became.

Grace, I think, is my favorite because she is just sweet. She's a sweet girl who only wanted one thing, and that was love. The love that she shared with her grandmother, the love that she had for her mother, and the love that she ultimately had with the father of her child, and the love that she had with her baby. And all of those things she felt were just the way that you're supposed to be, that is innate. That loving someone and wanting to be with them and wanting to do right by them and wanting to have a good relationship with them was something that we all should just do.

Now, a part of that is that she's young, and so she hasn't necessarily dealt with the harshness of the world. She ultimately does deal with the harshness of the world, but she always centers herself, no matter what the heck is going on—she always centers herself on love. She is always looking toward the sun and seeing a rainbow after the storm. That's who she is. And I think that her personality was a lot like my personality when I was younger. I'm not as naïve as her now, but for a very long time, that's the way that I looked at the world. And so, I really, really love Grace the most out of the three characters.

MH: I agree. Grace was definitely my favorite. And I was really heartbroken when her book ended, especially because I wouldn't get to hear Tina Lifford's voice again. (laughs)

DM: Oh my goodness. Can I just tell you that I've been listening to the audio version of my own book, which I can't figure out if that's narcissistic, or if I just really want to hear the interpretation of my words from the mouths of these three incredible voice actresses. I'd like to think it's the latter. (laughs) But Tina Lifford's voice, and the way that she wraps her voice around these words and around these characters, the dialect—she just nails it. She nails it.

We did a few auditions of the actresses for each one of the characters, and I just found that the ones who were reading the “Book of Grace” were sort of parroting how Southerners talk versus knowing how Southerners talk. I'm from New York, but I was raised by two Southerners—one from South Carolina, the other one from Virginia—and all of their friends were from the South. They were all a part of the Great Migration. So they all started life in the South, all came with the same customs, tongues, ideas, beliefs. They brought all of that up to the North, and they lived it in the North, right?

That's what I grew up in, that was the pool of being that I was swimming in as a kid. And so, that voice is familiar to me. It's not just familiar—it's in me. So when I hear someone making fun of a Southern accent or mocking a Southern accent or trying to do a Southern accent but you don't know really, it grates like a nail on a chalkboard. It's just terrible to me.

So Tina Lifford came along, and her voice, I knew from her being in Queen Sugar, was going to be perfect. And sure enough, I'm sitting here listening to it, and I am looking for time, clearing time out of my schedule, just so that I can listen to her read those words. She's incredible.

MH: She definitely is. And you also have [two] incredible narrators.

DM: Yes.

MH: You have Bahni Turpin as Lolo and Joniece Abbott-Pratt as Rae.

DM: Yes.

MH: Did you envision having three narrators when you were writing One Blood?

DM: I did. I did envision having three narrators, just because it's three distinct women in three distinct time periods, right? We get Grace's life in the '50s and '60s; then we get Lolo, in part in the '40s and '50s, but mostly in the '60s, '70s, and '80s; and then Rae is in Brooklyn in the '90s and the 2000s. Each one of them has a different way of talking, each one of them has a different way of expressing themselves, each one has a different level of freedom, right? Each one of them has a different age range and a different geographical location.

Most of Lolo's story takes place in New York and Long Island and in New Jersey. And that's completely different from the voice in rural Virginia in the 1950s and '60s. And then you have the child of hip hop, Rae, who has nothing to do with the Southern kind of sensibilities. She is very much a modern woman in Brooklyn, New York. And so, each one of them required a very different voice. I couldn't imagine Tina Lifford reading Rae's part, and I couldn't imagine Joniece trying to read Grace's part. Bahni's bad, so she would have been able to do whatever.

MH: (laughs) She could have done the whole book.

DM: Exactly. (laughs) But when I heard her voice, she sounded most like how I envisioned Lolo sounding. So it just made sense to have three different actresses for what is literally three different books.

MH: Your voice is also in the audiobook. You perform a poem, written by your daughter Mari Chiles, to open One Blood, and you also give voice to the author's note and the acknowledgements at the end of the audiobook. Why was it important to have your voice in the audiobook for One Blood?

DM: I just like my voice. (laughs) I've always wanted to have a radio show—it’s crazy. And I really like the way that my voice sounds when I'm reading, how it translates over a microphone. So I wanted to do something in my book—this is my 32nd book, and I've never done any voice work for any of my books. I wanted to do it for One Blood. And I wanted really very much to read my daughter's poem, which was important to me because her poem was sort of the jumping off point for the idea about nature versus nurture and how even if we are adopted, we are still a part of the family that is the human race. That is every bit as important as who is in your DNA. And so, I wanted that poem to be in the beginning of the book, and I wanted to be the one to read it because it is deeply personal to me. And then, so are the acknowledgements. The acknowledgement starts with a letter—the letter that I actually wrote [to my agent] when I was describing what the book was going to be about. That's a part of the letter that I wrote—I wanted that to be in my voice. And I wanted to say thank you in my voice to all of the people who brought me to this moment—my parents, my brother, my besties; the folks at Macmillan who really just took the helm of this book and shepherded it to this moment. I wanted to be the one to say out loud, "Thank you."

MH: That's great. Everyone, get the audiobook so you can hear Denene! (laughs) So, a major theme in One Blood is Black motherhood. We see a few variations of it—Grace is estranged from her mother and being raised by her beloved grandmother, Maw Maw; Lolo's mother died when she was young; and then in turn, Lolo becomes a very overprotective mother for her adopted daughter, Rae. What did you hope to convey with these different experiences of motherhood?

DM: I wanted very much to show that Black motherhood is not a monolith, that we all have a very different kind of way of approaching and being in that space as opposed to the way that society tends to look at Black mothers. They tend to look at us as, sort of like, the mammy who raises other people's kids but doesn't know how to raise her own. We can trust her to raise our kids, but her kids are going to be a hot mess, and it's because of her, not because of any of the “isms” that go into affecting how you can engage with your own family and particularly your children.

I wanted to be able to show Grace's love for that baby. She made that baby out of love—it wasn't an accident. Well, it was kind of an accident. But she made that baby, even though it was an accident, the actual act was love. That baby was a creation from love, right?

And then with Lolo, the way that she mothers, she mothers out of fear. And so, I wanted you to understand [that]. She is heavy-handed, she is abusive, she thinks that children are to be seen and not heard. She comes from a very … hard life, being raised as someone's daughter or in someone else's care, and to fight against that, she has a very specific notion of how she should raise her own children, particularly her daughter. But it's rooted in sort of the abuse that she suffered herself. So even though she feels like she's keeping her daughter from harm, she's actually the one who's doing the harm, and it's all rooted in trauma and her inability to understand or be able to lay on somebody's couch and just work that out, right? Like, she didn't have the money for that. She didn't have the wherewithal for that. Therapy was not something that Black women had access to or thought about in her time. And so, it all comes out in the harshest of ways, and the way that she's dealing with her child—that's real, right? That doesn't mean that she doesn't love her … I'm trying to lay out a foundational sort of understanding of why she mothers the way that she does.

And then, with Rae—Rae flips it. She sees how her mother mothers, and she's like, "I'm going to do the exact opposite of that because I remember what it felt like to be on the receiving end of that kind of mothering, and I don't want that for my daughter. So here's how I'm going to mother." And ultimately, Lolo comes around to that, which is, I think, the redemption part of the story, you know? It's the healing part of the story. And so, I wanted to show those different ways of making babies, raising babies, and loving on babies for the reader to understand that we are not a monolith. We have very specific reasons for why we mother the way that we do; here are three examples. And they're not the only examples of how Black women love on their children or mother their children—these are just three really solid examples of how that can manifest itself.

"I wanted very much to show that Black motherhood is not a monolith, that we all have a very different kind of way of approaching and being in that space as opposed to the way that society tends to look at Black mothers."

MH: Right. There was this redeeming moment for Lolo when she defended Rae when she was still nursing her daughter and all of the friends are like, "Why are you still doing that? Your eight-month-old has teeth. (laughs) Like, you shouldn't even be ..." But she really stood up for Rae in that moment, and I felt really proud of her that she wasn't siding with her friends. She was instead sticking up for her daughter and her choices.

DM: Right. You know, that particular scene was actually based off of something that literally happened between me and my mother and her best friends. I was breastfeeding my older daughter, Mari, and they just could not understand how I could be breastfeeding an eight-month-old. Like, what in the world is going on? And then, when I had my second baby at my god-sister's funeral, while we were waiting for the limousine to come and take her to the funeral, everybody was preoccupied with my daughter's hair. Like, why I hadn't braided it or put it into some puffs or, you know—

MH: Put some bows in it.

DM: Right, and put some bows in it. She just had this dope, curly, fluffy afro that I just loved, and it was a problem for them. And my mother stood up for me. I just didn't see that happening, but she stood up for me in both of those instances. Later, I actually got to ask her why. Like, "Quite frankly, I'm a little surprised that you stood up for me because I thought maybe you would feel the same way." And she's like, "That's your baby. It doesn't matter what I feel about it. If you want to breastfeed your kid, breastfeed your kid. You have your own reasons for why you're raising your kid the way you're raising your kid. And if you want her hair to look like that, then that's your business. You're the one who has to carry that baby on your hip, and you're the one who has to sit there and pull and tug at her hair when she's tender-headed. And if she doesn't want you pulling and tugging at her hair, and you like the way her hair looks, then rock with that. It's fine."

And that just made me look at my mother in a completely different way. That second conversation about my baby's hair came three weeks before my mother passed away. And that's what I mean by us having … like, finally getting to the point where I was brave enough to ask her, even ask her, the question. And then, she was open enough to actually answer it ... To [answer} me, her kid, who she was now looking at as a mother and as a woman. And then, she was gone three weeks later. So I never got to ask her the kinds of questions that I wanted to ask her about life, because she was gone. So you’ve got to be bold and brave and willing to walk through some tough conversations before it's too late.

MH: What do you think your mother would say after listening to One Blood?

DM: I think she would, hmm ... I would hope that she would see the intention behind the book and why I was doing what I was doing, why I wrote what I wrote. I would hope that she would understand that, again, I was asking those questions and trying to really understand and celebrate the lives of her and her friends, her sister-friends, who I used to sit and watch—you know, trying to be the quiet mouse in the room—and listen to them talk and laugh and engage and just really enjoy each other's company as women and to put being a wife aside and to put being a mother aside. I wanted to know about them. I would hope that she would read the book and understand that I was really trying to understand her.

I think, too, that she might be a little embarrassed by it, because she might look at it and be like, "Where did this come from? And why are you putting this business in the street? And what? (laughs) And oh my goodness, this is a lot." I think that she might read some of the pages and blush a little, but maybe she wouldn't. I remember when I was a kid, her reading Wifey, you know (laughs), and talking about it with all her friends (laughs) and me sneaking and reading the book and seeing how salacious it was, so maybe she would be fine with it. I don't know. My mother was a big romance reader. She loved reading, and she read a lot of romance books. And a lot of popular books. That's where I got my love of reading from. She might've been proud too. I would like to think that she would've been proud.

MH: I bet she would be. How important do you think it is to know who your mother is, to know who you are? And I ask that because I read—you did a recent interview in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution where you spoke about when you were ready to seek out your birth mother, she had, unfortunately, passed away before you could meet her. So, what happens if that question never gets answered? Where you don't know your mother? Does that in any way affect how you know who you are?

DM: Ooh, that's a good question. I can look—I found a couple of pictures of my birth mother after I discovered who she was. We have the same exact face. The same exact face. My daughters look exactly like her. My daughters look exactly like me. And I look at her face and I do wonder about what her life was like, what she may have gone through, what she may have experienced as a young, teenaged ... she had me when she was 19. And what she may have experienced going to that home for unwed mothers and having her either talked out of her baby or willingly giving me away.

"I don't think One Blood is an easy read, but it wasn't meant to be. It was meant to be a truthful read."

And there are just some things about me that do not come from my mother, right? And I wonder if that comes from my birth mother. There're specific things that I know are my mom's. My mom was very strict, but she also was very loving. She never had to hit me because her ability to express her disappointment was like getting a lash across the back, right? You didn't want to disappoint my mother. And so, I'm very good at doing that to my daughters. I never had to hit them. They were really clear that if I was disappointed that they had messed up, and they had to rectify it.

That's just one of the things that I got from my mother. Like wanting to make sure that my kids eat every night at the table as a family—I got that from my mother. Wanting to be a moral center for my kids—I got that from my mother. But there're other things that stand out to me that may be from my birth mother, and there's no way for me to know. So that's disappointing, but I don't let that rule how I feel about myself. I'm just happy that I have some small inkling of who she is, and that right now is enough for me.

MH: And One Blood is out in the world. (laughs) It feels like your baby—another baby is out in the world. So, just curious, what's next for you now that One Blood has been released?

DM: I have a companion book to this—it’s called What They Created Was Love—and it's a book about a birth mother and her having to go to one of those homes, like the home that I discovered that I was born in [and] explored in One Blood, just a little bit. This next book is going to be right there in the home with the birth mother, and you're going to understand how having a baby taken away from you, and having a family that's okay with that or that actually encourages that, how those two things can tear an entire family apart and really just wreak havoc on a mother who doesn't have access to her child. It's not going to be an easy read. I don't think One Blood is an easy read, but it wasn't meant to be. It was meant to be a truthful read. And so, I'm hoping that the same can be said of What They Created Was Love.

And then, I have another book that I'd like to write with one of my best friends. She's Ghanaian, and she lost her husband at a very young age. And she once told me about the traditions that she had to endure as a widower, and I thought the story was fascinating. So we'll be writing a book together that's kind of rooted in sort of what happens when this Ghanaian woman loses her husband and how life has to continue on through these traditions on American soil.

MH: I know you're listening to One Blood now, but I'm curious. Is there another audiobook that you listened to this year that you would recommend, and why would you recommend it?

DM: Yes! So I actually read and then listened to on audio Ocean Vuong's On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous. And just the words were super poetic in and of themselves. It made me want to throw my computer across the room (laughs) because it's just ... his writing is just insanity. His writing is so very beautiful. And as an editor—I am the publisher of my own imprint, DM Books at Simon & Schuster, and I know what it's like to edit someone—I don't think that I would've been able to edit him. I'd just be … just in awe of every word that pours onto the page. Kudos to his editor. But then to hear those words in the audio version was just every bit as beautiful as the words were in my head as I was reading them. And I just super encourage anyone to go ahead and download that one and just let it bless your speakers and your ears. It's beautiful.

MH: Well, Denene, One Blood is a truly beautiful book. I loved the generations of this family and their individual stories. I felt their pain, I felt their joy, and I felt their love. Listeners, One Blood is available now on Audible. Denene, thank you so much for joining me today.

DM: Thank you so much for having me and for your thoughtful questions, for making me dig deep. I appreciate it.