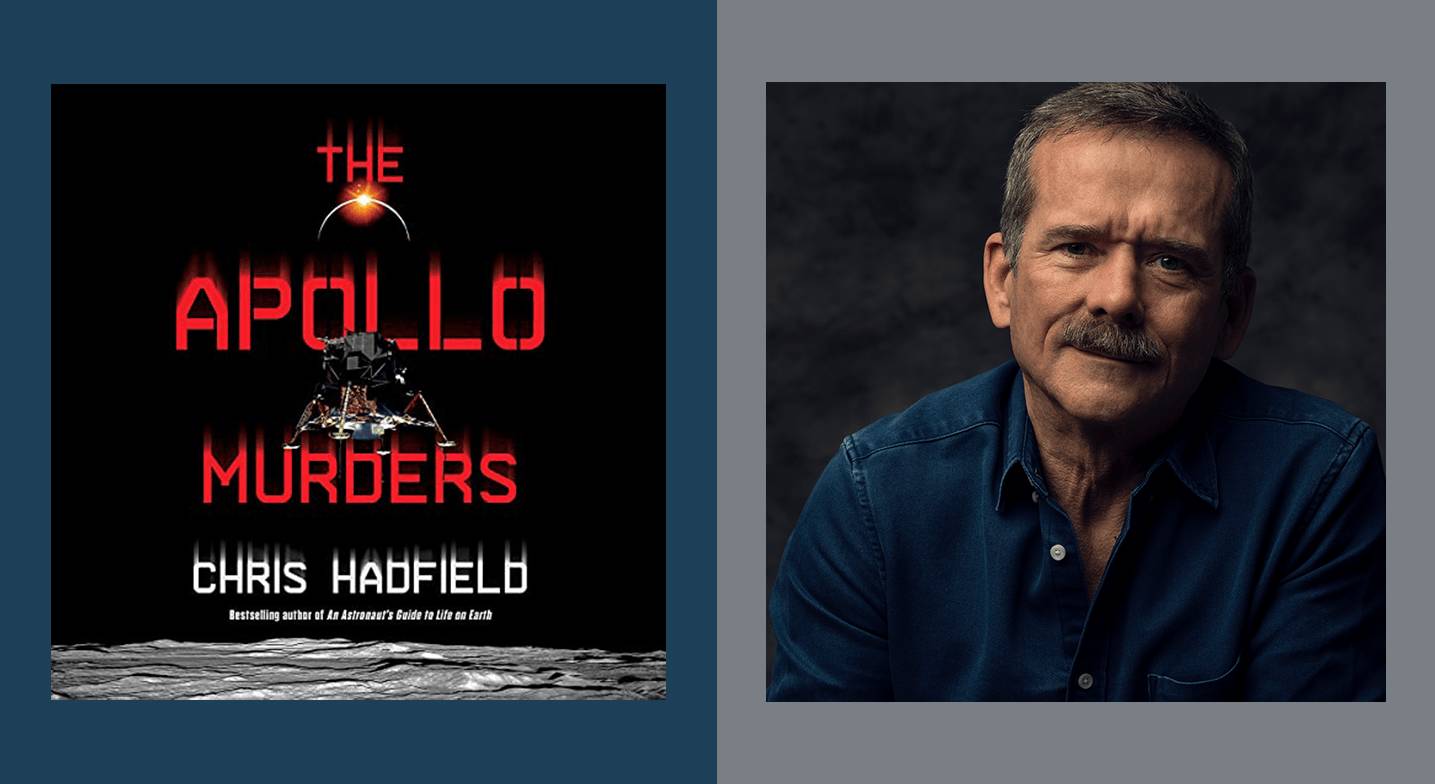

Kat Johnson: This is Audible Editor Kat Johnson. Today I'm honored to be joined by accomplished astronaut and best-selling author Chris Hadfield, who's here to talk about his first novel, the alternate history space thriller The Apollo Murders, narrated by the legendary Ray Porter. It is a great privilege to have you here with us today, Colonel Hadfield. Welcome.

Chris Hadfield: Please call me Chris. And boy isn't it cool that Ray Porter read this book? I'm so, so pleased, and he loved reading it too.

KJ: It's the coolest. We're going to geek out on a lot, I have a feeling, but I'm very excited to hear you say that.

Just to recap your considerable expertise before we get started: You're a decorated astronaut, engineer, and pilot. You've flown two space shuttle missions, and you're the former commander of the International Space Station. You're the first Canadian astronaut to walk in space. You've played the first acoustic guitar in space. You're the author of a best-selling memoir, An Astronaut's Guide to Life on Earth; a children's book, The Darkest Dark; and the photography book You Are Here. As the many people who have listened to your memoir or follow you on social media know, you've also done it all with humility and a contagious sense of purpose and wonder. It's such an honor to have you here, and your newest accomplishment is so dear to my heart. It's an intense Cold War thriller that imagines a terrifying Apollo 18 mission on the far side of the moon. What inspired this story and how did you come to write it as a novel?

CH: I was inspired by the real Apollo missions back when I was a kid. They kind of shaped most of the decisions in my life because I wanted to do that. I wanted to go walk on the moon. As a teenager I used that to help inspire a lot of the stuff that I chose. Learned to fly, learned to scuba dive.

But for this book I was really actually inspired by the title. A specific person in the publishing industry that I know and trust. A guy named John Butler at Quercus over in the UK. He came to me with an idea, and he said, "Hey, you know, I've seen some of the stuff you've written on the more fiction side and I think you could write a really good fiction thriller novel. And I've got this idea. What if you had a book called The Apollo Murders, and something happens to the crew on the way there and back? What do you think?" And I thought, "Well, cool idea, but I don't know how to write fiction. I have no idea. I don't know if I can do that."

"I've been in space for half a year, around the world thousands of times... So if you had done that, how would you share the experience?"

The idea just sort of languished for a while. But he came back with a publishing offer, which was pretty compelling. And then the pandemic hit, and I had an unusual amount of time. That combination of a cool idea and a publisher who was willing, and then a little bit of extra free time, allowed me to actually sit down and write The Apollo Murders. I'm tickled with how well it turned out. I think it turned out to be a really fun, interesting book. I'm looking forward to a lot of people reading it. And listening.

KJ: And listening, absolutely. I love that the idea was always a thriller, because I think for so many of us space equals terror. I wonder, is it that scary? And then how much fun was it for you to kind of play on those fears that people have about space?

CH: I've been in space for half a year, around the world thousands of times. I think it's 2,650 times around the world. So if you had done that, how would you share the experience? Or would you? Would you just keep it to yourself? Would you tell your mom? Would you tell your loved ones? Would you try and tell somebody else? And what would you tell them? You can talk about the facts of it, but how do you really give other people a feel for what it's like?

As you mentioned, I wrote An Astronaut's Guide, which is more than a memoir. It's like the rules for life to be successful. And then a children's book about fear and a picture book, but I thought, "Wouldn't it be a cool challenge to set for myself to put this into a fiction book so that people are right there in space when good things are happening and when bad things are happening? What is everybody's thought process, and how do we interact with each other, and what's it really like?" So that was a large part of my motivation as well in trying to really find a new way beyond the music and the master class that I did in the other stuff. A new way to try and share what is an infinitely magical experience of flying in space, and try and do it in a way that people would, without even knowing, just viscerally get it.

KJ: That's fascinating. So in some ways all of these mediums that you've explored, are you trying to relay and share your experiences with people?

CH: It's too good to keep to yourself. A lot of people in a lot of countries work really hard and trusted me to go do this thing really well for decades. And so I partially see it as a compunction, or a responsibility, as one of the very few people who has done this while serving as an astronaut. It would just be a shame if I squandered it and didn't ever let other people maybe see the world differently. So, that's part of the reason, but also it's such a fun challenge to try and weave a story into the reality of what was happening back at that time.

KJ: Right. So it's set during the Cold War. Why did you choose that particular timeline?

CH: As soon as I had the title The Apollo Murders. Okay, it's got to be happening in the '60s or '70s. Fine. And then it's like, where am I going to put it? Is it just murders that happen while Apollo was going on, or is it something in space? And if I could have tried to retro fit it into a specific spaceflight… But I thought, "Well, then I'm going to have to change what really happened. Instead let's just pretend that Nixon didn't cancel Apollo 18 and that it really flew. And then I looked—the internet is a wonderful resource—I went and looked, what were world events in early '73 and the spring of '73? And there was some really amazing stuff going on. You mentioned of course the Cold War, but also the end of the Vietnam War and the start of the whole Watergate scandal, and then the rise of women's rights and how that was being put into law in the United States.

The Soviets had built this real space station that was a secret spy space station, and the Americans had been building one and canceled it. And the Soviets had this rover on the moon. All these mysterious things happened in real life.

And I suddenly realized, "Okay, this is where the story has to happen because all of these threads give me the opportunity to weave something together that is almost all factual and find a plot through them." All that is hard to pull apart of what really happened and what didn't.

And in fact James Cameron, when he read the book, he said, "When you're talking about the book, say, 'This is what might have happened during the Apollo... or did it happen?'"

KJ: That's the experience of listening to the book. It's like, wow, where did this start to diverge from reality? Because it is so grounded in real details and your own experience. Was it tricky for you to balance getting those details right, and then just letting your imagination go in a different direction?

CH: I'm an engineer, and a fighter pilot, and a test pilot, and an astronaut. Details matter to me. Getting things right is what kept me alive all those years. You can't just wave your hand and pretend or pose. You actually have to know how everything works. And so to me I really value that. When I'm reading someone else's book and there's something that is patently false, it's not only disappointing, but I find it immensely distracting. It's like, "Well, if they didn't even check this detail, then what else?"

I really worked hard to get all those details right. The beauty of historic alternative history fiction is you can base so much of it in real events and real people. If it's 1973 there's a lot of video of Kissinger, and Nixon, and Haldeman, and the other characters in the book actually speaking. I tallied it up. I think over half the characters in The Apollo Murders are real people. Over half. Ninety-five percent of the book are things that actually happened. I've snuck the story in amongst all those things. That made it really fun. Like, how can I get this right but still push it to the edge of both technical behavior and human behavior so that this story holds together no matter who reads it, whether it's a psychologist or an Apollo fan or an active astronaut? So, yeah, that made it if anything a bigger challenge but also a more satisfying result for me.

KJ: That's really cool. And I love to see the sort of synchronicity between the sci-fi community and the real science and space community. I know you're a fan of Andy Weir's The Martian, and I know he's a big fan likewise of this book.

I want to talk to you about the audio experience. We already talked a little bit about Ray Porter. You did not get just any narrator for this book. You have narrated before. You narrated your memoir, which you did a fantastic job. But for this one you went for what I think was a fantastic choice, Ray Porter, who narrated Project Hail Mary [by Andy Weir]. How did you land on Ray Porter and what was your involvement in the process?

CH: I guess I approach everything the same way and that is, what does success look like? What am I trying to accomplish? This is true whether you're doing a spacewalk or writing a book or getting an audio version of your book. If this went perfectly, what would it look like? And then what do I need to do and change in order to get to a position where I have a high probability of that perfection happening? Let's do some work.

My wife is a voracious audiobook consumer. I've listened to a bunch, but I pale in comparison to her. She and I have worked together since we were teenagers. We've known each other almost our whole lives. And we talked about it, and then we listened to a bunch of different readers. We settled early that it has to be an American. You couldn't have a British or a Canadian accent in this because this is a very American story, and it has to be someone who can read sort of American military-speak and American techno-speak with a comfort, and who can read in the manner of how people talked in 1973 as well, with those nuances and innuendos. Also someone who can do accents; there's other countries involved here.

And you're right. I read Astronaut's Guide to Life on Earth, but that was largely my story, and my ideas, and my experiences, and it wasn't fiction. It took me like three and a half days, and I had to keep rerecording when my stomach rumbled and stuff like that. But this one is theatrical. There has to be wonder, and excitement, and inflection, and women's voices, and men's voices, and you have to do Nixon, and you have to do Kissinger. There's just no way I could. I knew immediately, obviously I can't do this.

We listened to a bunch of different audiobook readers and settled on a top few. We kind of did a blind taste test. Who just does this the best? Then we submitted those to the American publisher, and then they contacted a bunch of people to audition. Our number-one top choice was Ray Porter. "Let's hope Ray has time to do this." And he did audition.

Listening to his version it's like, "Yep." I developed a little rating scale: How well do they do accents? How well do they get techno-speak? How well do they do all the emotional range? All of that. Are they convincing as mission control, and as Gene Kranz? So when Ray said, "Yes," happy dance in my household. And the cool part is now I've gotten to know Ray, and we ended up working on this together. That's been a real silver lining.

KJ: Have you listened to his performance?

CH: Yeah. What I offered to them right at the start was, "Hey, if you're having any dispute or thought at all, just text me or call me, or whatever you want." Multiple times I get this text at some weird time of day from Ray saying, "Hey, how do you say this word?" or "What did you mean by this?" That was really good. When they got their first recording of it done, then I worked with the publisher and with those folks.

"The beauty of historic alternative history fiction is you can base so much of it in real events and real people."

I actually listened to the whole book and made notes, and then went back. Ray and the director/producer and I sat down, a long afternoon from like midday until late, and went through every single patch where we had to go back and fix this, and fix that, and fix that. I think he just did a bang-up job. In fact, there are several sections of the book that are way better on audio than they are on the page, where he just brought it to life. I was nervous, you know? How's this going to turn out? And he was just—Ray, on his own accord, because he's a huge space fan and knew who I was, Ray put in a few little grace touches that people are going to love, the folks that know to pick up on them. I really thanked him and respected him for that.

KJ: That's so cool to hear. To your point earlier about seeing details show up in books that would kind of take you out of the experience, that happens in audio as well. Something gets mispronounced or not said the right way. It does take you out of it. I appreciate that you and Ray were so detail-oriented in working together.

CH: Spaceflight is an immensely cooperative and participative venture. We couldn't do the things we do without a huge team of folks working together. Writing a book, and publishing a book, and getting it recorded and out there in all the different media, that takes a huge team, and it takes cooperative effort.

I think a lot of people fondly think you can just sit and write a book, and the rest of it magically happens or something, but it's all part of the same process. Having the freedom and the trust from the publisher to work directly with Ray to make sure that we made it as good as we possibly could, I think was a real boon.

KJ: Yeah. I'm curious to know too, we talked a little bit about seeing gaps in sci-fi sometimes, where many things aren't as reality-based as they could be. But have you read books or listened to books that you feel do capture that amazing experience of being in space? Have you seen other people do it in a way that you recognize as true to your experience?

CH: The answer is normally no, but once in a while yes. Once in a while someone does a really good job and gets it right, and I'm very thankful when they've put in the work to do that. For me obviously the technical piece is important. You shouldn't make stupid technical mistakes, especially if the information is readily available. It's just frustrating.

But even a lot of authors, whether it's science fiction or in my case I call it alternative history fiction, they might get the technical details right, but you've also got to get the people right. They have to behave like those people would behave. Astronauts are a weird subset of society. They're not the same obviously; otherwise they wouldn't be picked to do what they're doing. They're by no means anywhere near perfect or anything, but they're just different. The way they react, and the way they talk, and the way they think, and how they would value things. That gets reflected so badly in so many things.

The best factual book I’ve ever read in that genre is by one of the astronauts, one of the guys on Apollo 11, Mike Collins, who orbited the moon while Neil and Buzz walked on the surface. And he wrote a book called Carrying the Fire. It just tells the story, and it was hugely inspirational to me as teenager to read that.

But when I read Andy Weir's The Martian, sure, I loved all the technical stuff, and he got his chemistry right. He had to exaggerate a few things, like wind on Mars and how the spacewalk would work. A little bit of poetic license. But he got how astronauts—Mark Watney on the surface, played by Matt Damon in the movie—Mark could have been just anybody in the astronaut office. That's just how we are. Very technically trained, smart, physically fit, hugely resourceful, and eternally optimistic in the face of what you think would be overwhelming negativity. And that's just, hey, that's the type of person you want to fly a spaceship. That's the type of people that they pick. That's what I told Andy. I was like, "Andy, how did you even get that right? You don't even know that many astronauts."

In Project Hail Mary I loved the interplay that he had in there as well. His characters were very believable in their subset of society, and to me that's really important. I made it really important to myself to try and do that right in The Apollo Murders.

KJ: Oh yeah. Don't you think Kaz and Mark Watney would get along?

CH: Oh yeah, of course. They'd sit down in a bar and immediately have 99% of nodding their heads a mutual understanding of what's actually going on. But also a similar value system, right? And a similar sense of what's important in life, and where the joys are, and where the sadnesses are. Yeah, I absolutely think so.

KJ: Oh that's so cool. I do want to ask you a couple of burning questions that might be on the minds of people who follow your career. Today, as we're recording this interview, it's the day after the launch of the Inspiration4. I would love to hear your thoughts on that. What do you see as the next frontier of space exploration, and what are the big blockers that are facing us right now?

CH: Huge respect to those four people. They took an enormous risk to fly a rocket ship. It's still very dangerous, and as you and I are talking about this, they're still in orbit. I'm sure they're floating next to that window and reveling in the hard-earned and brand-new perspective of the world much as all of us have who've gone before them.

But what is always been the obstacle, Kat, is technology. It's like, why didn't we get to the South Pole until 1910 or 1911? Well, we just couldn't. Our ships weren't good enough, our navigation wasn't good enough. We had to invent a lot of stuff until suddenly it was just barely possible. It's like, no one got to New Zealand until 800 years ago. Nobody.

KJ: Right.

CH: No human being had ever been there because we hadn't built sailing ships good enough, or circumnavigated the world until Magellan. No one had ever flown a powered airplane until 1903 because we hadn't invented the good metallurgy that would allow it. The wheel was invented 6,000 years ago. All of those things, the technology leads the exploration opportunity. And when I was born, nobody had flown in space. Spaceflight's younger than I am. Because we just hadn't figured it out. But once we start figuring stuff out we accelerate.

All of that early work as we were guessing and trying to get the designs right, and the space shuttle was immensely capable, but it was also a fundamentally very flawed design. We only flew it 135 times, and two of those times we killed everybody. All of that is a huge learning process by which we can get to where we are today. And 50 years from now we're going to look back at Inspiration4 and go, "Pfft, how pathetic and how ridiculous."

KJ: Right.

CH: "And how rudimentary." It's like looking at a car from 1940. You go, "What were they thinking of?" You know? So technology moves along and enables opportunity. And the cool part is, we are at one of those real accelerating moments because we've invented GPS for three-dimensional navigation. We have high-speed computing. A lot of the thought can take place in the computers onboard. We understand hypersonic aerodynamics and the thermodynamics of the atmosphere. So that we are so much safer than we were.

"We're people. We're multifaceted. We can do different things with our 28,000 days. So challenge yourself to try to do something new, and then use that experience to understand and appreciate the world better and share that joy and experience with other people. To me that's the very essence of living."

And that is allowing not only for four non-professional astronauts to safely get to orbit, but we're on the cusp now of going back to the moon much more often, and much, much cheaper, and much more safely than we did back in the Apollo era. That's really exciting to me because it's just the daughter of technology, and that's what opens all of our understanding and exploration.

I'm excited for Inspiration4 not because it's some big step. It's four people for three days in a spaceship. We've been doing that for a long time. But it's the demonstration of the technological capability, and what kind of doors that's opening for what's coming next: permanent usage of orbit around the world, settlement of the moon. So people are regularly living there, and then figuring out and inventing things to cross the ocean that's between us and Mars. That's where we are in history right now. It's pretty cool that I've been a part of it, but it's happening while I'm writing about it and still watching it from right here on the sidelines.

KJ: Yes, absolutely. Speaking of technology, I also wanted to ask you about the James Webb Telescope, which I think is launching on December 18, which is replacing the Hubble Telescope. What would be the next deep-field image that we might expect to see?

CH: Hubble Telescope has been unprecedented. Maybe the telescope that Galileo used back in the early 1600s where he saw the moons of Jupiter and the moons of Saturn, and realized the universe doesn't revolve around us. The use of that telescope changed our fundamental understanding of our place in the universe. So did Hubble. Hubble taught us the age of the universe. And it has showed us… Whenever we think we see something with some other telescope over the last 30 years, then we get Hubble to look at it and show us what's really there. It's been that revolutionary, and that good.

But it's an old telescope. I mean, we launched it right at the start of the 1990s. Who's driving a car from then now even? And yet we went up and repaired it several times and upgraded it, but still. So with the James Webb Space Telescope, as you say finally launching here hopefully just before the winter break, it is another step forward in capability to be able to peer back in time, to be able to look at planets around other stars, to be able to look into what we can see of the weirdness of physics, of black holes, and warping of light, and such.

If you close your eyes you'll only have a very reduced understanding of the world around you. As soon as you open your eyes you'll learn a whole bunch. If you open your eyes and put glasses on or a microscope in front of you, or binoculars, or a telescope, you can learn even more. And the more powerful the technology, the deeper our chance of understanding.

I fear for the James Webb Space Telescope because we're launching it to a place where we can't go fix it. So I surely hope, touch wood, that we've got everything right and that wonderful telescope can do what it's designed to do. That's a gamble you have to take. But it stands ready to show us things about the universe that are beyond our current comprehension. And to me that's pretty exciting.

KJ: Speaking of that, I have to ask because lately there's been a lot of talk about the mysterious flying objects reported by naval pilots and the US Congressional Report on the investigation. Have you ever seen anything that you couldn't explain personally?

CH: Oh I see stuff I can't explain every day. I can hardly explain anything [laughs], but as soon as I see something I can't explain I don't immediately say, "You know, I don't what that is. That must be intelligent life from another galaxy." Or "What? Where'd that come from? That doesn't make any sense. Where, where?"

But at the same time there's an unlimited number of stars out there. That's what the Hubble and other telescopes have shown us. It's actually a number, but the number is so huge it may as well be infinite. And every one of those stars has planets. If there's an essentially unlimited number of planets in the universe, then it's kind of arrogant, and unlikely, that we weren't the only life that developed. That seems improbable.

KJ: Right.

CH: It's also immensely improbable that someone covered the vast distances between stars and got all the way here and found intelligent life that's already living on a space station, and all they did was allow themselves to barely be seen at the edge of some Navy pilot's head duct display. That doesn't pass the common-sense test to me either, but I sure don't know everything.

And also, what's the harm in people thinking that there are UFOs? What's the harm in it? I don't know. It's not… It doesn't matter what you believe. You can believe anything with absolutely no information. I'm much more interested in the facts. And the facts are, we've never seen life anywhere but from Earth.

KJ: Right.

CH: But that doesn't mean there isn't. And it's fun to think about UFOs and aliens and stuff. I think about it all the time.

KJ: Okay, thank you for indulging me with that. The other thing I really wanted to ask you—the breadth of your experience as an astronaut playing the guitar on the ISS, you're also an accomplished downhill skier, and you can write a rip-roaring novel, as we know—I'm just curious, if you had to hazard a guess, what is the secret in your approach? Or is there something in your background or process that you think kind of enables you to take these creative challenges on?

CH: I think part of it is I've always had dangerous professions. As you say, I raced downhill as a teenager, and then I became a pilot young. I had my pilot's license before I had my driver's license. But then I was a fighter pilot, test pilot. And I lost at least one good friend a year violently just doing their job in public service. It reinforced to me the fragility and the brevity of life at how life goes by fast. And so don't squander it. Don't spend your time doing stuff that isn't important to you or that doesn't matter to you.

And don't get distracted. Spending a whole afternoon on a YouTube wormhole where suddenly you're watching cat videos or some tennis player you've never heard of and stuff. It's like you come out of that, and you realize I just spent three hours and accomplished zero with my life. I didn't learn anything worthwhile either. I've always instead thought, "What would be a fun challenge? Like, how fast can I run a mile or can I learn five words of Japanese today?" You know, to challenge myself with things that then will increase my ability to do other things in life to make it all sort of accumulative. So that when the next day comes I'm not starting from zero. I'm starting from a position of advantage.

Look at how I'm actually apportioning my time during the day. What am I actually doing with my days, and is this what I want to do? When my best friend died on squadron back when, late 20s, he had a horrible accident and crashed, his wife—they had two little girls same age as my wife and my two little boys—and his wife said to me, "We had so many plans."

That really struck home into my heart that don't just have plans but actually make a decision of something you want to get done this hour, or this day, or this week. And then find out what you don't know how to do yet to get that thing done. "I want to learn how to solve a Rubik's cube." "I want to have a stronger back so my lower back doesn't hurt so much." It doesn't matter. And then understand what you really need to do in order to get to that position, and then start doing it. You may find out, like me and dancing, "Nope, I'm not a good dancer. It's never going to happen for me." And so I've already done that as well as I can. Let's move on and challenge myself with something else.

One of the great science fiction authors said "specialization is for insects." We're people. We're multifaceted. We can do different things with our 28,000 days. So challenge yourself to try to do something new, and then use that experience to understand and appreciate the world better and share that joy and experience with other people. To me that's the very essence of living. And it's the essence of why I gave myself the task of writing The Apollo Murders, and I'm just looking forward so much to people's reactions to it. The people that are actually in the book, I want to see what they say, but everybody else [too]. To me it's more like a sharing of imagination and joy. And that kind of guides everything that I choose to do in life.

KJ: Thank you so much for that. That's a beautiful note for us to end on. It's an amazing book. Congratulations. I know that our listeners are going to love it. Thank you so much for your time today.

CH: And thanks to Ray Porter for bringing that book to life. I'm really—

KJ: Huge thanks to Ray Porter.

CH: I really, really love the way he did that.

KJ: Absolutely. Chris Hadfield's thriller, The Apollo Murders, is available on Audible now. Thank you so much, Chris.

CH: Thanks, Kat.