In crime stories, both real and fictional, the perpetrators of violence receive outsize attention, while victims are more regularly relegated to the background, playing a supporting role in what's often treated as the killer’s story.

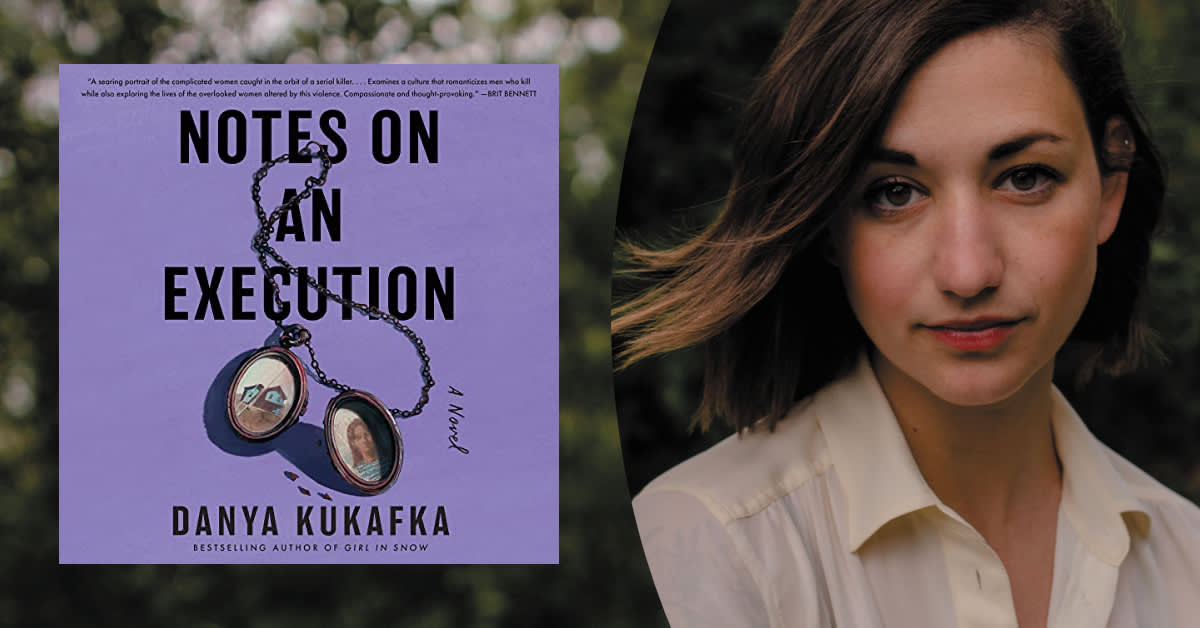

Over the past few years, more crime writers are pushing back on this tradition. Novelist Danya Kukafka, whose first book Girl in Snow explored the intricate effects of a girl’s mysterious death on her community, is digging even deeper with her newest thriller, Notes on an Execution. Though it opens on death row in a Texas prison, where serial killer Ansel Packer awaits his fate, the story quickly unfolds to dwell on the inner lives of others in the crime's orbit, from the killer’s mother to the determined police investigator intent on justice for the victims. Told in the second person and read in alternating sections by performers Mozhan Marnò and Jim Meskim, the novel’s structure succeeds in fleshing out the true toll of the murders while capturing the humanity of those at its center. Kukafka told us about the haunting themes and dark questions that shaped the novel.

What were some of the cultural influences behind Notes on an Execution? Did you want to counter the many serial killer narratives we see in true crime and crime fiction? I grew up watching network crime television—Criminal Minds, CSI Miami, and Law & Order SVU are still some of my favorites. I consumed so much of this content over so many years, the larger questions of this novel began to percolate very naturally. These shows generally offer a fairly reductive (if addictive!) narrative structure: the body is found, the detectives catch the killer, justice is served. I began to wonder about the human nuances running beneath these stories, the darker and more pervasive questions about good and evil, justice and truth, which the well-worn plot arc tends to skim over. I wanted to tell the story underneath.

“There are so many movies and podcasts and documentaries out there that focus solely on perpetrator, the evil madman and his depraved psychology—the longer we look at him, the more interesting he seems to become.”

What are some of the ways that perpetrator- and violence-focused narratives might perpetuate harm? Was there a particular story or cultural touchpoint that influenced your thinking on this? We love serial killers. It’s a cultural obsession I’m still trying to understand, as I both participate in and attempt to defy it. There are so many movies and podcasts and documentaries out there that focus solely on perpetrator, the evil madman and his depraved psychology—the longer we look at him, the more interesting he seems to become. I do think this perpetuates harm, as it turns our collective focus away from the victims of violence, their families and their communities. I struggle with Ted Bundy, particularly, for this exact reason. He’s held up regularly as a cultural icon, the face of the handsome, cunning mastermind. In reality, he was just a man who decided to kill women. There are much more interesting focal points in the story of Bundy’s crimes, but the narrative centers him and his media-manufactured persona every single time. Researching Ted Bundy and reflecting on how he’s been portrayed informed many of the choices I made while writing Notes on an Execution.

How does recentering crime narratives around victims, communities, and persons close to the case help create better crime stories—ethically, narratively, or otherwise? Honestly, I wrote this book without worrying too much about the ethics of the narrative itself. I just wanted to tell a compelling story about real women and their real lives, while also investigating these tropes about violent men. I do hope that crime stories begin to take a more ethical approach, but I really just wanted to dig deeper, to find the true story hiding

beneath the one we’ve seen repeated for decades now. For me, it felt less like a moral undertaking and more like an excavation.

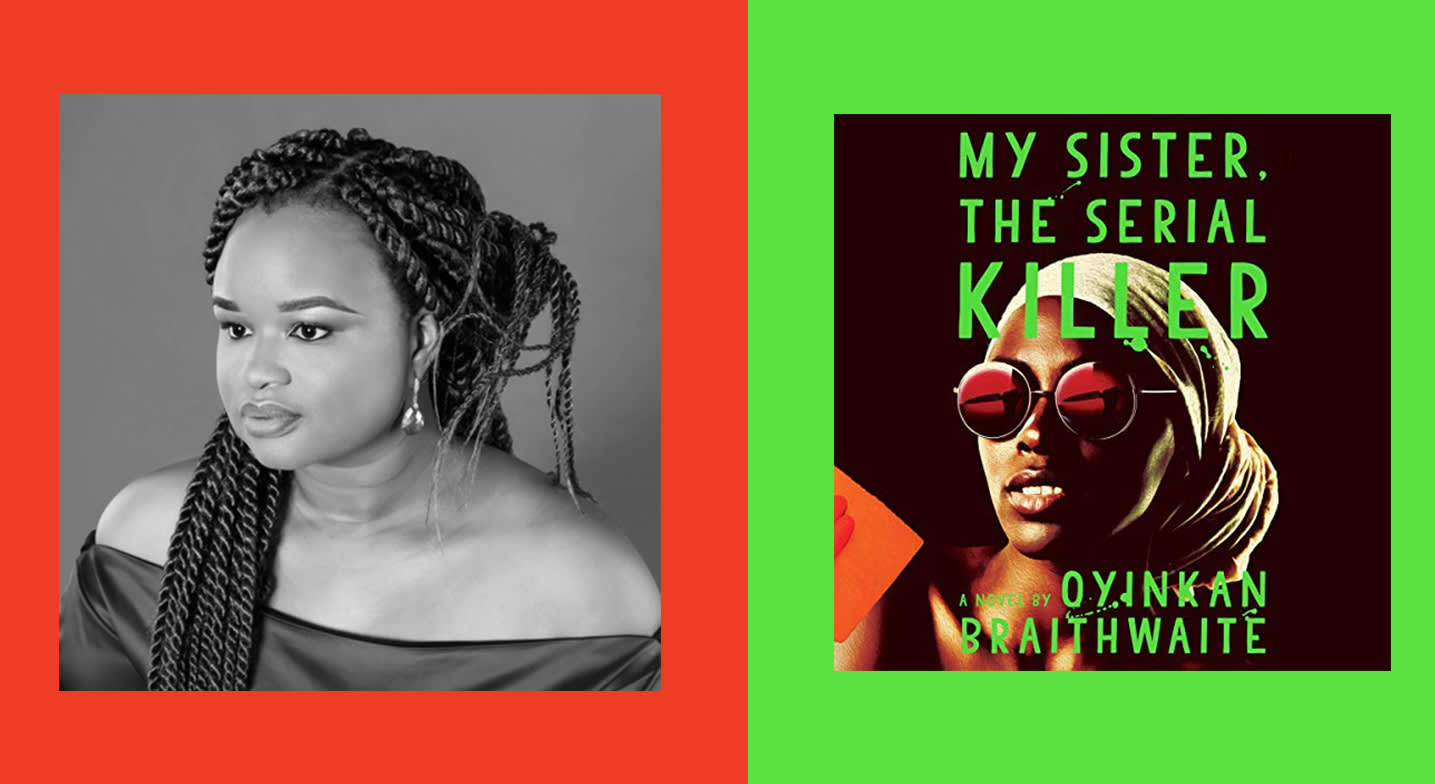

Are there any works of crime fiction or true crime that you recommend for folks interested in victim-centered (or non-killer-oriented) narratives? Absolutely! I recommend Long Bright River by Liz Moore—this is a gorgeous book about sisters, which both examines and inverts the structure of the crime novel as we know it. I also loved My Sister, the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite, a slim and addictive novel that plays innovatively with format and perspective.