Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

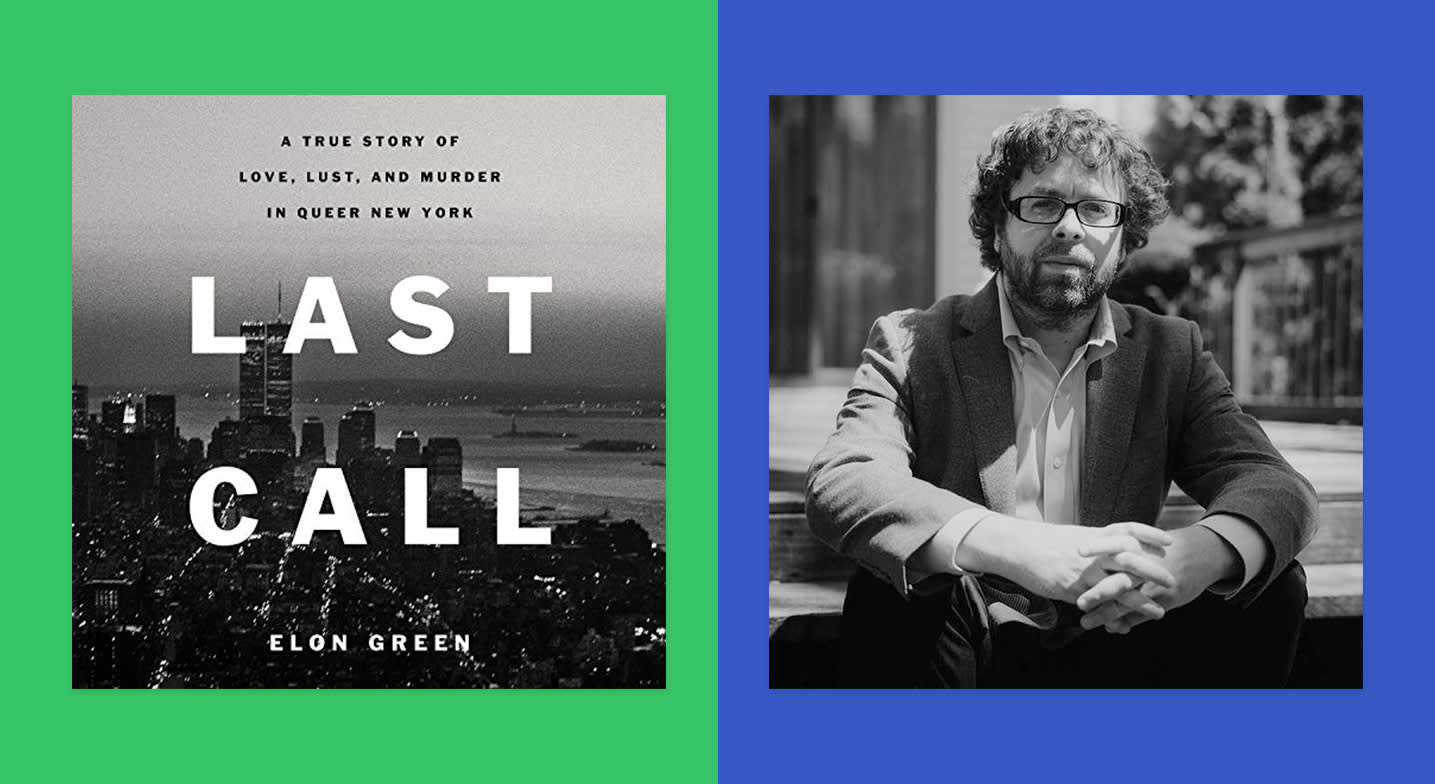

Michael Collina: Hi, I'm Audible Editor Michael Collina, and today I'm here with Elon Green, the author of Last Call: A True Story of Love, Lust, and Murder in Queer New York. Thanks for joining me, Elon.

Elon Green: Thanks for having me.

MC: Your book is an incredibly well-researched investigation of a series of crimes against gay men at the height of the AIDS epidemic, and it's one that hasn't really been told before. How did you first come across the story and this case?

EG: I originally had plans to expand an old story of mine about a series of murders in San Francisco called The Doodler Murders into a book, and I had attempted to do that in 2016, and I failed. But I got very obsessed with the idea of still writing about a forgotten case and writing about queer life and the political backdrop, and so I looked for another case. And just by accident while reading a back issue of The Advocate, I found a story about this case, which, at the time, was unsolved. And the more I looked into it and the more I read about the victims, the more I got just immersed….

MC: So throughout this book you made a point to call out that this is a story about queer crime and that queer crimes have often been underreported and underinvestigated. You also highlighted the general distrust, and even at times a disgust, toward the gay community at the times that these crimes were committed. I'm sure those feelings were exacerbated by the AIDS epidemic, which, as we mentioned, was raging at the time. But aside from all of that fear and bigotry that you called out, do you think there was anything else that may have made this case fly under the radar for so long?

EG: I do think that there were a series of circumstances which really conspired to make people forget it. As you say, obviously this is happening amid the AIDS epidemic and sky-high homicide rates in New York City. The sad fact is that four murders over three years is unlikely to be noticed when you have 2,000 homicides a year in the city. But you also had the fact that this was multijurisdictional, and though these men had been in Manhattan, that's not where they ended up.

"...Murderers tend to be extremely uninteresting... I was more interested in the life of someone whose entire existence had been reduced to at best an obituary in a local paper."

But also once the murderer was arrested—he was arrested in mid-2001—you know, that was shortly thereafter kind of swept out to sea by September 11, and by the time the trial happened it was four and a half years later, and people's attention spans just simply aren't that long. So, at the time when I discovered this case, I was surprised that it didn't have a Wikipedia entry, and that's still the case. I'm much less surprised now because I have a much greater understanding of why people don't know about it.

MC: It sounds like it was really just the perfect storm of unlikely events happening.

EG: I also think that there's a larger point to be made about this. There are many murders that happen every year, everywhere, and the percentage of them that get written about is already small to begin with. In that sense, it's much less startling that people don't know about it.

MC: That's so interesting…. In addition to taking a procedural look at this investigation, you also took the time to paint this really beautiful and vivid picture of queer New York, and you paid particular attention to the bar scene and all the hangout spots of the era. Why was it important for you to dive into all this detail with the different bars and cultural scenes of the queer community of the time?

EG: Part of it was selfish, because this is the early '90s New York. It's, to some degree, just written about ad nauseam, or on the cusp of Sex and the City,it's Manhattan, it's an exciting period, so to have found some sliver of it that had been neglected was on a very basic level deeply lucky.

But at the same time I felt that if I was going to write about the lives of these men, I was going to have to explain why they'd come to New York in the first place, given that at least two of them lived elsewhere, and the only way to really do that was to situate the bars that they went to in the greater ecosystem of the bar and club scene of New York. Added to which, it's a lot of fun. Despite the darkness of that period people still wanted to have a good time, and I think that was worth fleshing out.

MC: Definitely, and as you mentioned, each of these men had their own stories and they're all very interesting stories of where they were before they came to New York, what their lives were, and I found the re-creation of each of the victims' lives so interesting but also really integral to understanding a lot of that discrimination these men were facing and dealing with every day. Was that your intention from the very beginning, to focus on that discrimination and that difficulty for them?

EG: Yeah. That's something that survived from the get-go. Not everything that I wanted to do at the beginning, or didn't want to do at the beginning, ended up being what went into the book. But writing about their lives and the societal constraints they were living under was actually largely the attraction of writing the book because my interest in the murderer was, and remains, pretty minimal. I wanted readers to get a sense of their lives because it was the only way that they would feel their absence as acutely as I wanted them to.

MC: That's so interesting. So, you've told us a bit about why you were interested in this case and all of these victims. But I want to know, why did you feel like you were the right person to tell their stories?

EG: I think that's always the question with stories like this, but particularly stories where, in my case, I'm a straight guy telling a queer story, and I do wish I had some grand answer for you, but I don't. I discovered the case at exactly the right time, and lots of people were alive and were willing to talk, and I think that because the case was still so under the radar, the fact that I wanted to write about it at all helped cement a fair amount of trust.

These were people that had waited decades to talk about it, and to talk about their friends and their loved ones. That's just kind of a long way of saying that I was the one to tell their stories because I wanted to tell their stories.

MC: Well, I think even if not a grand answer, that's a great and admirable answer in my opinion.

EG: I appreciate that, because it is something that I thought about a lot. Every now and then I would think, "Well, should I be telling this story?" My way of answering that was to basically let the engine of the story be their voices and the activist voices and the people who were there. So, to some degree, I was just the conductor.

MC: You mentioned that you are a straight man telling a queer story. Did that fact bring up any specific challenges or maybe even unexpected benefits while you were doing your own investigation and interviews for this?

EG: Almost entirely the latter. I think that my being straight when it came to talking to lawyers and law enforcement was a positive because they could not assume that I had a "bias" or agenda going into this. And then, I think when I was talking to the queer community they tended to be pleasantly surprised that I cared at all and were willing to talk. I interviewed people again and again over several years. At a certain point you just build up a base of trust and they're going to talk to you because you care. But I do think that that actually helped.

MC: I love that you say that, because personally I was really, really intrigued by one of the points you made in the story about a lesbian detective who was working on this case. You brought her up and you mentioned that a lot of the folks she was interviewing were actually more relaxed and more open with her than maybe would have been with any other detective.

Do you think that might be a sign that we need more queer individuals in law enforcement and criminal justice? Or is it maybe a sign that there just needs to be more training on how to be more empathetic and more caring toward the people they're investigating?

EG: So, this is a question that’s obviously on the forefront right now, especially in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests and events like that, and I'm very hesitant to advocate for more queer people to become cops. I think that existing police should simply treat the people in their communities like human beings.

"I immediately chose David because I could imagine him having a drink with me at the Townhouse"

MC: I agree with you there. There are so many infuriating details in the story about police indifference, anti-queer violence, and a lot of the challenges that came about trying to prosecute the perpetrator at the trial. Looking at criminal justice today, what do you think has gotten better, and what hasn't?

EG: I don't know that it has. The criminal justice system and the legal system are still heinous. All that has happened, probably, is that there's been a shift about whose ox is getting gored at any given time. But if you were to look at the criminal justice system in Louisiana, you still have people serving life sentences for crimes they committed when they were in their teens. I'd be hard-pressed to say that much has improved.

MC: Do you think there's anything in particular that investigators can do or learn from this particular story to avoid those pitfalls in that current status?

EG: Yes. But I think they won't. I think part of this just comes with the territory. I think in order to learn lessons from this case you'd have to completely reorient what law enforcement is. But also, the fact is that to learn anything from any single case, the case has to get so much attention that it can't be ignored.

A good example of that is the David Berkowitz Son of Sam murders. Detectives learned that parking tickets were something they ought to look for when they were trying to catch criminals. It was just one of those things that became part of their training. But, you know, those were notorious. Everybody knew that case. The fact is, that it's unlikely that anybody is going to learn a lesson from the Last Call killings, even though they should.

MC: Well, since you are telling the story and really giving it a lot of audience, I'm going to remain hopeful on that one, that maybe one day they will take some of those lessons from the story that you decided to tell.

EG: That would be nice.

MC: We kind of touched on this a little bit earlier, but you make an interesting choice not to bring in the perpetrator of these crimes until almost midway through the book, and you really spent most of your time bringing the victims to life as opposed to focusing on the killer. Is it fair to say you were much more interested in the victims rather than the killer himself?

EG: Absolutely.

MC: Why was that?

EG: Because murderers tend to be extremely uninteresting. At bottom, they're just people who did terrible things, and they're even less interesting if they haven't taken responsibility for what they've done, as was the case here. So, of course, I was more interested in the life of someone whose entire existence had been reduced to at best an obituary in a local paper.

MC: It sounds like it's really hitting on that hidden history aspect, telling a story that people wouldn't necessarily know and that people should pay more attention to and learn about.

EG: Absolutely. By focusing on the victims, this was my way of saying, to some degree, "The way you consume true crime is wrong, and I want to reorient you toward thinking about it like this."

MC: In a more ethical viewpoint. In a more ethical way, and really just focusing on and thinking about the victims.

EG: Yeah, but I would also argue that it's just a far more interesting way. In the end, murder investigations tend to play out the same, no matter where you are. They're either solved or they're not, and where the real differences are, are in the victims.

MC: That's a great way to think about it.

EG: The thing is, if you're going to spend two years on a book, three years on a book, you have to keep yourself interested too.

MC: That's very true. So, true crime and criminal histories are hugely popular right now and it's a genre that's been evolving over the years. Were there any authors in particular whose work you looked to for inspiration while you were writing this one?

EG: I did make a point of actually reading very little while I was working on the book itself because I didn't want to be influenced by anybody else. However, David Grann's work has always been an inspiration and touchstone for my own, in part because he's a friend but also just because his work is so extraordinary, and, that's, to a great degree, where my victim-centric view of events comes from.

He took great pains to situate the crimes of Killers of the Flower Moon within the era of Oklahoma 100 years ago. He spent years re-creating the life of the Osage Indians and the Osage Native Americans. And I felt like trying to do the same was the least that I could do.

MC: That makes a lot of sense. So, as we previously discussed, you spend a lot of time detailing the victims throughout this book. The crimes committed against them were really brutal, and I have to imagine that you spent a lot of time interviewing friends and loved ones for each of these victims. Did you find that at all difficult to write about?

EG: It depended on the day. If I was writing about a death, it was really hard. The days that I spent writing about Michael Sakara, the fourth victim, the scene of him meeting the murderer in the bar was very hard, and I didn't particularly want to write it. But, you know, if I was writing about their everyday life or their romances, it was a pleasure. In general, I was very excited to get up each day to work on the book, because having this material was such a privilege.

MC: That is so fascinating. I love hearing that…. Speaking about the process, let's talk about the narration for a little bit…. Last Call's performed by David Pittu, and he does a really great job bringing a suspenseful but sophisticated approach to telling the story. What level of involvement did you have in selecting him as narrator?

EG: Well, I was given a choice of two actors, and I immediately chose David because I could imagine him having a drink with me at the Townhouse. He seemed to have a perfect voice and a perfect demeanor to re-create that period. It didn't feel like he was a tourist. It felt like he had lived it.

MC: In other words, he was the story, he was the voice, before you even had heard it.

EG: Yes, absolutely. I listened to about 30 seconds of his audition before I realized there wasn't going to be anybody else.

MC: Oh, wow, that's incredible…. Thanks so much for taking the time to speak with us today, Elon. I'm so glad to see this case finally getting some of the attention it deserves, and I want to thank you for taking the time to explore the systemic issues and injustices against the queer community that have gone long undocumented. I can't wait to hear what you'll have for us next. Elon's book, Last Call: A True Story of Love, Lust, and Murder in Queer New York, is available on Audible now.

EG: My pleasure.