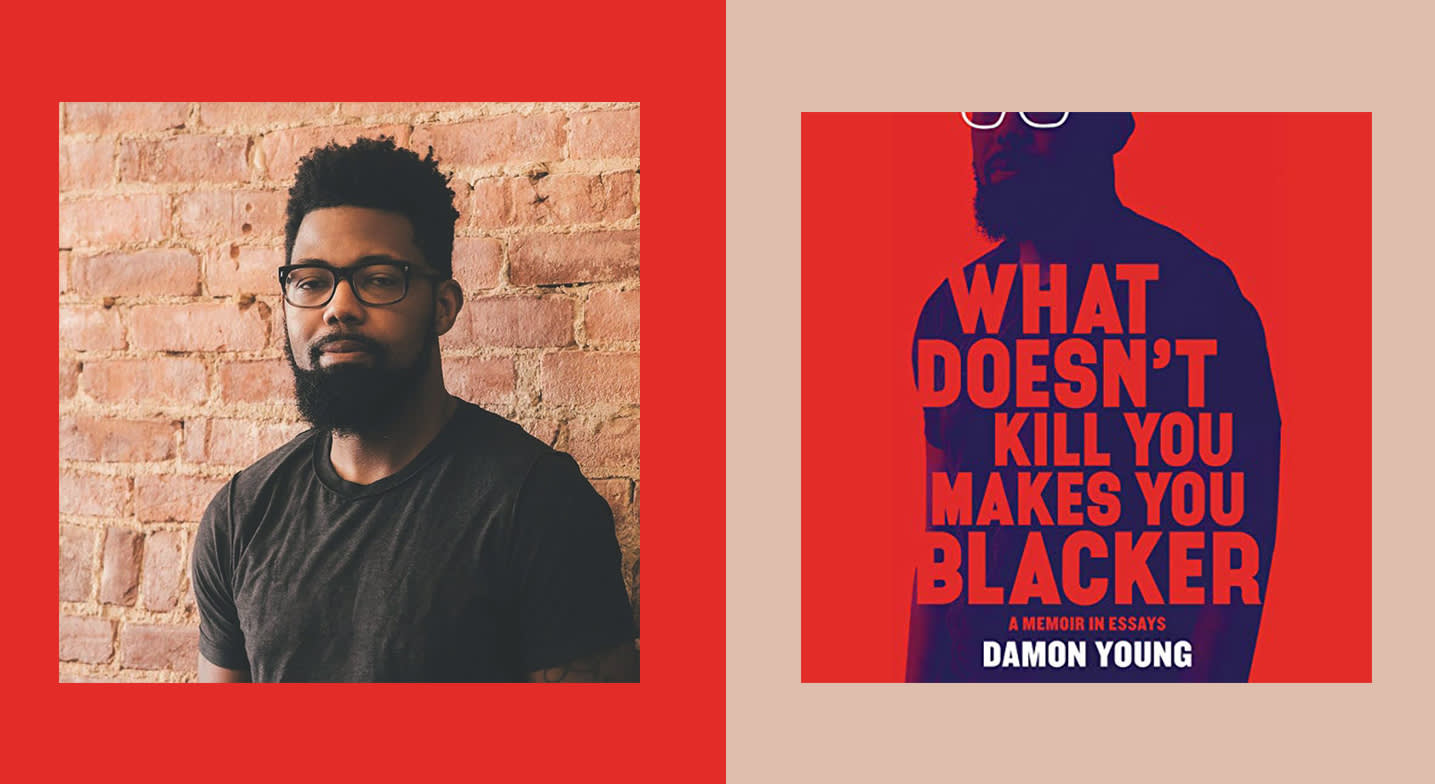

I've been reading Damon Young's writing for years over on VerySmartBrothas.com, the pop culture criticism site he co-founded in 2008, and his funny and insightful writing regularly makes me laugh out loud at my desk. His cultural reach has grown and he's now also a contributing writer at GQ, often tackling matters of race and class. With his new memoir, What Doesn't Kill You Makes You Blacker: A Memoir in Essays, Young connects the dots between the personal and the universal as he studies how he interpreted black masculinity growing up and how he sought to live it as an adult. He confronts many uncomfortable realities about black life in America, including the underemployment issues that stymied his father and the health care system that discounts black women's pain and contributed to his mother's death.

Listen in on our conversation as he talks about what it meant to hold both his childhood and his ideas of manhood up to the light, how he's dealing with family stories now being out in the public, and what it was like to record his N-word laden book while negotiating the difficult hard "r" or soft "a" emphasis issues that ensued. Spoiler: it came up a lot.

Note: Portions of this interview contain mature language and themes. Listener discretion is advised. Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

Abby West: Hi, this is Abby West, your Audible editor. And I am excited to talk today with Damon Young, author of What Doesn't Kill You Makes You Blacker: A Memoir in Essays. Damon is the co-founder of VerySmartBrothas. He's also a writer at GQ and is one of our most-read writers on race and culture today. He's written a provocative and very funny memoir in essays that explores the ever-shifting definitions of what it means to be black and male in America. Welcome, Damon.

Damon Young: Thanks for having me.

AW: Very happy to have you. You've entered this world of not only writing a memoir where you're exposing so much of yourself, but you also recorded the audiobook which we're going to talk about a little bit later. But tell us how this book came together. You've been blogging since 2002. You started VSB in 2008 with Panama Jackson and Liz Burr. And at the time, I think you wrote about it as being sort of a tongue-in-cheek dating and relationship advice platform. And it's really morphed into so much more. Could you talk about how you got to where you're having this moment in life?

DY: I feel like there are two answers to that question. The first answer, I guess, could be that this book started when I was born. And the process, it's just so much of what went into the writing of the book, and the experiences that the book drew from began at birth, maybe began in the womb. So there's that answer.

But I guess the more, I don't know, the more practical answer is that it's a book that I have been writing for a couple of years. It actually came about after I got hooked up with my agent, Tanya McKinnon, through a mutual Facebook friend. And she said that she was a fan of my work, and asked if I needed representation, and I did. And I mentioned to her that I had a couple of ideas in mind already for books. And with both of those ideas, she was kind of like, "Yeah, those are cool... [Laughter] but I think I have something better for you." And I didn't agree at first because that's just how I am. My default is "no" to everything. And eventually I agreed, even though I kind of agreed in my head even when I was saying no.

And she just felt that instead of writing a book that is almost like a VSB sort of book, where it's chapters about race and racism and black culture and black people and whatever, write a memoir where people are able to connect with you. And also a memoir that has a bit of a narrative theme, and you can inject those pieces on race and on masculinity and on culture and whatever, into the story that you're telling. So that's what I attempted to do with What Doesn't Kill You Makes You Blacker.

AW: That concept of being able to weave in your personal narrative with the larger narrative... how was that for you to put into practice? Did you immediately see the moments, the touchpoints that were laid out for you in your past? Or did it take some digging?

DY: Well that's the thing, the first chapter of the book takes place when I'm 15 or 16 years old. So I had to go back and I guess re-remember things that happened to me. And think about them in a way that I've never thought about them before. And in some instances, think about them for the first time in 15 or 20 years. And through that process, I did have a few epiphanies. I did have a few moments where things that I have always kind of just believed to have happened a certain way... Or things where I maybe assign blame to something happening to the wrong person and reflecting on it now at 40 or when I was 38 or 39 while writing this book, it was just like, whoa. So much of my past had been I guess ... I don't want to say filtered, but almost cultivated through this very positive and very just hyper-flattering lens.

"[It] makes me wonder how much of a role socialization played in me having certain ideas of what a man is supposed to be, what a husband is supposed to be, what a wife is supposed to be, and what a woman's supposed to be in a family unit."

How I remembered things in the memories that had cemented, was not the same as the memories that I re-remembered while writing this book. I feel like I'm not making any sense right now, like I just watched Inception. And I think that I have Inception brain right now. Like literally, right before I got on the call, Inception was on and I was watching the first 10 minutes of it. And I think I'm turning into Christopher Nolan right now. So if those answers sound too Nolan-ey, my apologies.

AW: [Laughter] No worries. But I think what you're getting at is basically like what you write in the book. You grew up in the hood but you didn't know you grew up in the hood until you were not in the hood, because it is just the way of life. How do you know the bigger impact of the things you experienced growing up until you measure it against something else sometimes, right?

DY: Yeah. And even with that point about growing up in the hood ... when people first hear my background or hear my story, or even the people who have read this book already, often they're very shocked. Just like, "Oh, my god, I had no idea that things were so rough and that you came from this place." And when I was growing up, I didn't feel that way. I didn't feel in danger, I didn't feel poor. I didn't feel some of the more negative aspects of growing up in certain types of neighborhoods that people assign. I did feel like I wanted to be maybe a little bit more middle class. And our parents didn't have a car, and I wanted to be able to have a car so I could have a license, so I could go on dates and take girls on dates in my car and all of that type of thing.

But I didn't feel in danger.

AW: Right.

DY: I never felt threatened. And perhaps that's just me being a naïve 15 and 16-year-old, and just believing that I'm invincible. But I think back to some of those instances that I talk about in the book, and some of the things that I experienced back then. And the 40-year-old me kind of shudders at the thought of doing some of those things. What I remembered and what I re-remembered while writing the book, there was a bit of a contrast between those two things.

AW: That must have been quite the journey to sort of scrutinize it and hold it up against what you're going back and looking and finding that middle ground, or finding what is true and what is applicable. Because you managed to pull out things that you absorbed, even the necessary reliance on reliable transportation in order to stay out of recurring unemployment, as that situation with your father. There are things that you may not have interrogated as a child, but really you absorbed and have pulled in.

DY: Yes. Yes, definitely. And even getting back to my dad where, in the book, I definitely talk about how he was underemployed for a very long period of time. And I do talk about the effect that that may have had on our family, and even on my mom's health. And even after writing the book and reading it and thinking about it, again, I can't help but wonder how much of my feelings about my parents are gendered.

AW: Right.

DY: Just in terms of, if it were my mom who was the housewife and stayed at home, and my dad was the one who was out working every day, I probably would've felt differently, you know? I might've written the book differently. And the thing is, I love, my parents. My parents are my favorite people. Two of my favorite people. My dad's my homie. But still, I wonder if some of the questions that I ask of him, and I ask of just our relationship in the book, I would've asked if the gender roles were reversed.

And again, that just makes me wonder how much of a role socialization played in me having certain ideas of what a man is supposed to be, what a husband is supposed to be, what a wife is supposed to be, and what a woman's supposed to be in a family unit. And I think that, although I'm having this thought now, the book at least makes the effort in interrogating them. And maybe not so much with my parents, but with, I guess, myself and the relationships that I have with women throughout my life, really.

AW: And that's fair, that's what we all do is sort of sadly bring all of our childhood things forward with us and either play them out or try to work through them. But it takes a little bit more work to really look at that and see where it's going. Part of that, you're looking at masculinity and black masculinity growing up, and the posturing, and all of these things that we just sort of took for granted that young black men had to figure out on their own. And I hadn't really thought about the mental machinations that go through that. What was that like for you to sort of dig through?

DY: Yeah. It's surreal, I guess, thinking about just the level of performance...

AW: Right, that's the word.

DY: Yeah, that I believe was necessary in order to, I don't know, to be sufficiently, heterosexually black when I was younger. I want to try not to speak of that in a past tense also, because I still believe that there are certain parts of that performance, certain parts of that need for a certain type of validation, that are still with me. Even as I recognize them and I try to extract those parts from me, there's still kind of that need to put on a certain face, or to have these certain completely useless but also validating benchmarks of masculinity. And finding a way to reach them somehow.

And it's like this really just f***ed up game where you recognize the futility of attempting to reach these things that no one can reach, but you still play the game. And even as I recognize that it's a game, it is difficult to kind of just put the controllers down and step away from the console, you know? And I'm a work in progress. Maybe by the next book I will have been able to have done it completely.

"When it comes to my politics, or how I think about myself, or how I interact with the universe, I don't want to be a person who kind of just stagnated in 1997, or in 2007, and refuses to continue to evolve. Refuses to continue to grow."

Maybe I'm being a bit too hard on myself. Maybe I've made the sort of progress that I hope that I've been able to make. But I recognize that my work there isn't done. It may not be done for a while.

It may not ever be done.

AW: Well that's the more mature answer. To acknowledge that, because the person you need to worry about is the person who thinks they're fully formed already and there's no more work to be done.

DY: Yeah. You just want to keep evolving, you know? A couple years ago, I went to my 20-year high school reunion. And I had a decent time there. It's one of those things where you go to a reunion and you realize that social media has made the reunion kind of obsolete, because you already stay in contact with all the people that you want to stay in contact with anyway. But it's still good to just see people in the flesh and see some people that you may have even forgotten about, and just have certain conversations that you had 20 years ago.

But anyway, I'm at this reunion and there were some people there who, you could very obviously tell that their fashion kind of stopped in 1998 or 1997. Like they were still wearing the jerseys, the hoodies-

AW: Oh my god.

DY: The things that we wore when we graduated from high school, except for the fact they're grownups wearing these clothes that were fashionable then but are pretty outdated now. And I don't want to be that person when it comes to, not necessarily fashion, although fashion too. But when it comes to my politics, or how I think about myself, or how I interact with the universe, I don't want to be a person who kind of just stagnated in 1997, or in 2007, and refuse to continue to evolve, refuse to continue to grow. I just don't want to stagnate.

And to be quite honest, I feel like writing the book kind of helped that evolution too. Just putting some of these things in front of me and thinking about them, and also kind of being able to read and actually see some of the thoughts that have been just circling around and marinating and whatever in my head for so long.

AW: Okay. I feel like this is also a perfect time for this kind of self-reflection and sort of public introspection, you know? Kiese Laymon's book, Heavy, was our Audiobook of the Year last year. And in large part because of his vulnerability, and his ability to sort of dissect this, and switch up this usual narrative about black men. It's a very complicated matter to be able to lay it all out there, and to be very clear about how not all black men, you know? Hashtag, not all black men. This is a very not monolithic experience, that there are so many nuances that are also very resonant and connect with a lot of people.

And I think you've been doing that, and especially with this book. What was it like for you to first write it and get it out into the world, and then to go into a studio and not just read it, but to sort of relive it in a different way?

DY: You know what? I think I was more affected by the actual physical act of reading something out loud and recording, than I was by I guess the emotional impact of hearing my words spoken out loud. And I think that's because of the way I write. And when I write things down, I read it out loud to myself. So reading the book and having it recorded wasn't the first time that I had heard my words out loud, because everything I write, I actually do read it out loud to myself. My wife calls it ghost whispering, where whenever I'm reading something that I wrote, instead of just silently reading, you know how I'll be whispering things to myself, and she'll be like, "You're over there ghost whispering again."

So yeah, it wasn't really this huge emotional impact for me with reading the book out loud and recording it. I was more impacted by just the physical act of reading, which was very intense and gave me a lot of gas. Like, I did not anticipate how much burping I would have to do, because it was basically record for 20 minutes, burp for five. Record for 20, burp for five, and then just rinse and repeat, and drink some water or tea or whatever in between. And make sure not to eat a huge lunch because you'll be burping, instead of for five, you'll be burping for 17 minutes, every 20 minutes. So yeah, I wasn't ready for all the burps.

AW: How long did it take you to record the whole book?

DY: It took four days. We did have to go back and re-record a section that I had changed in the book because after reading it out loud for probably the 50th time, I realized that, you know what? These sentences just don't work the way I want them to, so let me just change them up a little bit. And then I had to go back and re-record it.

AW: Okay, okay. So, you liberally sprinkle the N-word throughout your book. How did you address that in the recording?

DY: I do? [Laughter]

AW: Yes.

DY: [Laughter] I mean, I say it. And it's funny, because I say n***a a lot and I say n***er a lot also. And in the recording, I had to make sure to kind of just stress that I'm saying n***er at this time, like I'm saying it with a hard R, so I need to stress the "er." And what ended up happening sometimes is I'm saying it with this very, almost like a British accent. Like, "the n***a," or, "the n***er." And actually that sounds more Australian probably than French, but I was saying it with an accent that wasn't natural, because I was trying to just make sure that the distinction between those two words were very clear. And obviously, that's clear on paper, but out loud it isn't always as clear.

And I know I have this Pittsburgh accent already, which a lot of people aren't really used to hearing, and I have enunciation issues and I have a thick tongue I guess, so all those enunciation challenges converged to make n***er and n***a a bit of a challenge.

AW: I can imagine that would be the case for sure, just for anyone. But it's definitely something that you become very cognizant of when you're recording, you know? It's just a thing. But this just sort of highlights the fact that you are funny and you're known for being funny.

DY: Oh, thank you. [Laughter]

AW: We've made it a very heavy conversation, but you are very skillful with the wordplay, with sentences that often just make me laugh out loud. Just because they make sense once you land them, but I would never have landed them that way, you know? I was going to read a couple of examples, just little things. And there are big setups and there are little lines, like one line, "For two years our next door neighbors were a family of somewhere between six and 149 people." And I knew exactly what you meant, and I knew exactly where that next couple of sentences were going go because that's a familiar setting or scenario of the neighbors where 20 sets of family members were living there, you know? Those kinds of scenarios. Or saying that Pittsburgh itself is so segregated that "any place within a 10 mile radius of the city with more than seven black people there at one time feels like the Essence festival."

You're able to make references that are inherently evocative and funny. And when did you realize you had that kind of wordplay fun?

DY: When did I realize I was funny? [Laughter]

AW: Yes, that you could be funny in writing, especially.

DY: That's a good question. When did I realize that I could be funny in writing? I would say we'd have to go back probably to around seventh or eighth grade. And I actually mention this in the book about how my dad would rewrite the essays that I would get for English class or Social Studies or whatever, and add all of this punch and add all of these verbs to them. And sometimes he would make things funny, also. And I guess that was my epiphany, like, holy s**t, you could be funny on paper?

AW: Right.

DY: Like, there are ways to massage punctuation. And there are ways to use rhythm, and subvert expectation, and use just even consonants in a way that is funny. And for a person like me who has always been very introverted, and has always had jokes for people that I just kept in my head, writing them out and being funny on paper was always a cathartic activity. It's like, finally, I have the space to say all these things that have been just sitting up here, just gathering thoughts. Finally, I have a platform for it.

AW: Right.

DY: And it's one of those things where I've always been very into comedy writing. And whenever there's a group of comedians talking about the writing process, I'll go down a YouTube rabbit hole and watch five or six of those videos a night. And just the way that jokes are structured, and the way that humor kind of builds tension, and then the punchline releases it. So it's a combination of reading and watching other people who I believe to be funny. And also, whatever I bring to the table, and whatever has been just stored inside of this egghead of mine. And the paper, and the book, and whatever other platforms I have are finally opportunities to kind of get that out.

In the book I talk about never being really good at ripping. And ripping, for those who aren't familiar with that term, is a Pittsburgh area term for playing the dozens or roasting or clowning, or whatever. Whatever you call it wherever you're from, where a group of kids just talk about each other's parents, talk about each other's girlfriends, talk about each other's face, whatever. And this is a thing that I was never good at as a kid, and I wasn't good at it because I would take everything so seriously. I wasn't one of those kids who you called me ugly and I'd be ready with a comeback immediately. If you called me ugly, I actually like, holy s**t, I might be ugly. I believed it. And then my feelings would be hurt, and then I wanted to fight.

So there was no in between, like I could come back with equal fire. That wasn't me. It was, okay, you ripped on me? Now I wanted to kick your ass. So I avoided situations where a ripping session could happen. But when you're a high school kid, that is virtually impossible. Particularly if you're a high school kid who catches buses, who plays basketball. I mean, you're going to be in locker rooms. You're going to be at the lunch table. You're going to be on the bus. You're going to be waiting for the bus. You're going to be in homeroom. And that's when that s**t happens.

So again, I never was really good at that. But I did have things that I would just store in my head. Just perfect insults that I just wouldn't say, because I feel like they were a little bit too cruel. [Laughter] So I'd just keep them to myself. And again, the internet has been a lifesaver because now I have a platform where I can just say them.

AW: You'd posted [on social media] when you were in the recording booth. And it made me laugh out loud, and I was showing people at work a picture. I literally cannot have my voice saying the N-word on recording here. But it said "Pictured: an N-word with sporadic enunciation issues recording the audiobook for What Doesn't Kill You Makes You Blacker. Not pictured: the face said N-word made when reading 'solipsistic', and realizing he's never actually said that word aloud before."

And it made me laugh because I'm like, I have no idea how I would say "solipsistic". And I had to go look it up. So I know you had fun with some of those words.

DY: Yes. Oh, yes, there are so many words that I have no idea how to pronounce. But I know them, and I use them and I write them. But when it comes time to saying them out loud, I'm like, holy s**t, can I call a friend? Like I turn into Who Wants to be a Millionaire, and I want to be able to reach out to people and have them assist me. And that happened while recording the book, that's happened on panels before. That's happened in conversation, where I'm thinking of a word and it's called to me. And then I remember mid-word, like, holy s**t, I do not know how to pronounce this.

Like one time, and I probably shouldn't even be telling this story but I'm going to anyway. It was four years ago, I was on a panel somewhere, and "zeitgeist" was the word I wanted to use. And at that point in my life, I had never said it out loud. But I had used it multiple times in writing and whatever. So, I'm about to say it, I realize I don't know how to say it, so I really quickly mumble [zeit-eh-gest-ey].

AW: I'm cringing for you. I'm cringing for you right now, yeah.

DY: "The zeit-e-geist-ey mandates that." And I just said it. I just spit it out my mouth and hoped that no one on the panel or no one in the audience caught it. And I don't think that anyone did. Again, having the Pittsburgh accent thing helps me, because I think people just attribute any sort of mispronunciations, or even malapropisms, to just, oh, he's from Pittsburgh. That's just how they talk there.

AW: Right.

DY: So yeah, I definitely said zeit-e-geist-ey. I added like, three syllables to it. I made it like the name of ... like, a yoga shop. Like, the name that they chose after Lululemon. It was going to be zeit-e-geist-ey or Lululemon, and they chose Lululemon.

AW: You see, the people could've also just thought you were being funny, so it's okay.

DY: Hey, you know what? And that's where that humor comes out because I can always blame my mistakes, oh, I was just telling a joke, that's all-

AW: Yeah, there you go.

DY: Just being funny.

AW: Well, thank you for sharing that story. You also share a lot of very personal and revealing things in the memoir. Let's not get into your prayer habits as a young person, there's a lot there and those were some very self-deprecating ones. But then you also shared some things that, I guess, are surprising to me maybe only because in large part I knew you publicly, and we have numerous friends in common in the writer's circle. But talking about how you and your wife, Alecia, first came together, and revealing the affair you had before you came together for good. Talking about the admittedly ill advised, rape responsibility piece and that fallout.

What was it like for you to sort of open that up and know that you're putting it out into the world, and it's going to exist, and you're going to have to potentially talk about it? And did you and Alecia talk about that? How did that go for you?

DY: Well, which part? The part with my wife or the part about the piece that I wrote?

AW: Both ... My question's a larger question about deciding to be very revealing in certain things. And particularly with the affair and with Alecia, because that's not just you, that's not just your story. So some things are just your story and some things are not, so how was that process like for you?

DY: This entire book process from the writing of it to the lead up to it, which is happening now, has been just like this stew of anxieties and neuroses all just swimming amongst each other. And this is one of them, that people are going to read this and read some of these very vulnerable and very personal things, particularly this chapter, which deals with a subject that, to be honest, is still very ... it's a very sensitive subject for my wife, Alecia. And she wanted me to write it, and she was fine with me writing it. And I made sure to take as much care as possible, while also kind of telling the truth.

But it feels like, I don't know ... I used the analogy yesterday, when I was talking to someone about this book, of I'm creeping up on a haunted house as I approach the pub date. A haunted house that's like, filled with gold. That once you can stay in this house for like an hour or a day, then oh, you're going to win this gold treasure. But it's still a haunted house. And that, right there, is the biggest haunt for me, is that people will read this and feel a certain way about her, or feel a certain way about my dad, as we brought up before, I talk about my dad. I don't really give a s**t really how people feel about me, or in terms of if ... how they feel about the things about me that are in this book.

AW: Right.

DY: I obviously do care how people feel about me, but my level of f***s about what I expose about myself is near nil. But I still have a smidgen of a f***, so I'm not going to say I'm completely f***less, but that last f*** is holding on by a thread. It's like an undershirt that you've had for like, a decade, and there's holes. And the sleeve is connected to the collar by a thread, that's that last f***. It's just hanging and it's just ready to be thrown away but I can't, because for sentimental reasons. I remember when I bought that shirt. That shirt took me through some really good times. [Laughter]

But anyway ... That chapter is tough. It's going to be tough for people to read, you know? It's important because, as the book continues, it tells this, I don't know, almost culminating story, and I wouldn't have been able to just introduce my wife like, oh, by the way, I have a wife now, without telling a bit of the story about how we actually met, and how we came to be in a relationship together. But I'm not at a place yet where I feel great about people knowing these things about people close to me.

AW: Yeah.

DY: And I realize that if I'm writing a memoir, then yes, you have to share some personal details and details about people in your life. But that's probably the part of this whole process that has been the biggest struggle for me.

AW: I can definitely understand that.

DY: Even with the blessings. Even with Alecia and my dad both saying, "I love what you wrote. Go ahead and say it." Even with their permission, it's still, I don't know ...

AW: Well, I think you should definitely take comfort in the fact that it was definitely written with care and comfort. And it comes across that way. And it's important because it is important to the whole story, but also because people are going to recognize themselves and their people, you know? It's not, as much as people may get up in arms, they are not uniquely to you experiences, they are universal. They are resonant. And I think that's important, it's always an important part of writing a memoir because it's a connective tissue for us. So there's that, and I want to thank you for doing that. I know it's probably very, very hard. But as with the rest of the book, it definitely brings across a conversation that needs to be had about black masculinity.

I really do enjoy this book and I'm glad that you've done it. And I hope that the whole experience is pretty fantastic for you in the end, even through all the neuroses.

DY: You know what? I'm learning something new every day, particularly with the lead up to the book and the lead up to the release date. And I thank you for liking the book, I guess. I don't know what I ... See, that's another thing. I don't know what I'm supposed to say when people say that they enjoy reading the book other than thank you. So, thank you.