Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

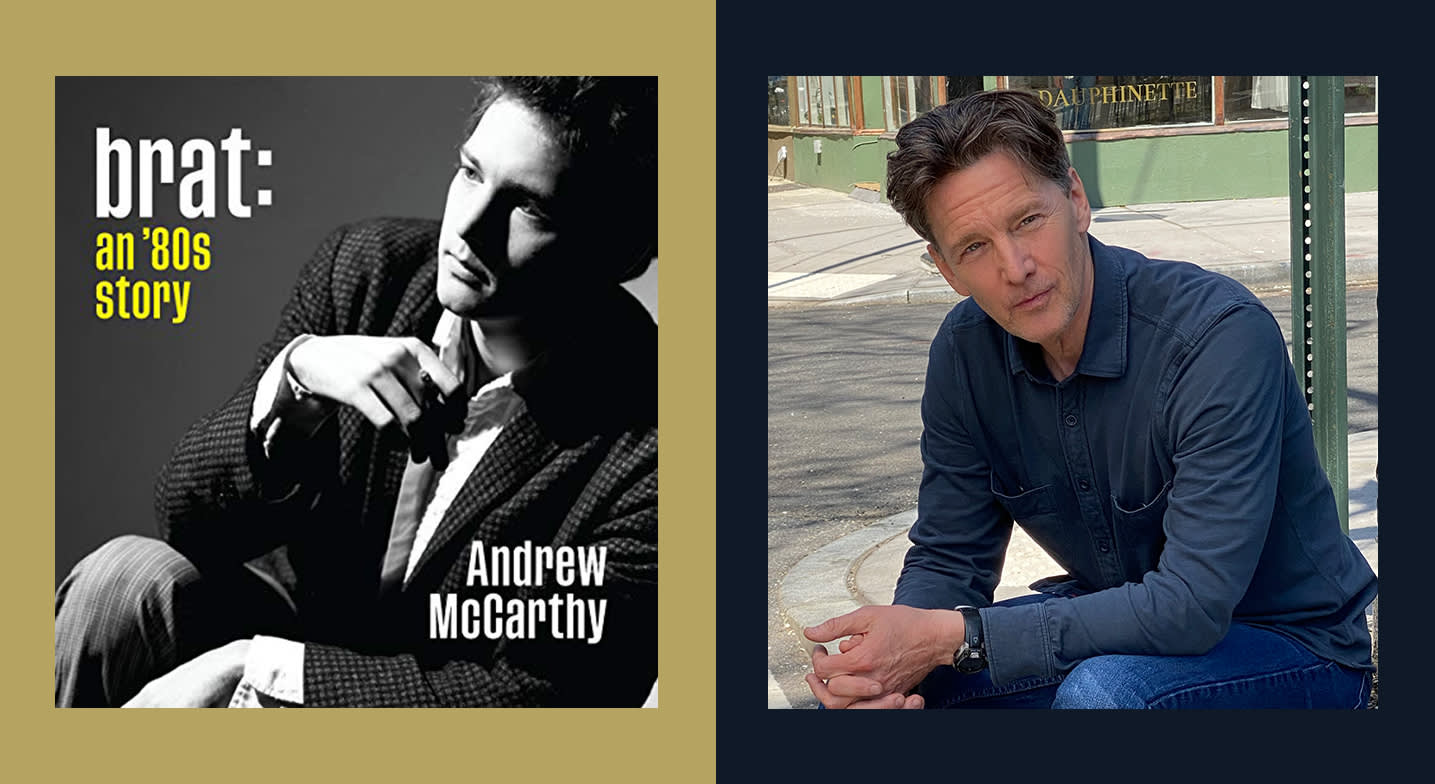

Edwin de la Cruz: Hi, I'm Audible Editor Edwin de la Cruz. Today I'm talking to Andrew McCarthy. You may know him from starring in the '80s classics Pretty in Pink and St. Elmo's Fire. But he's also a New York Times best-selling author and a director of shows such as Orange Is the New Black, The Blacklist, and Gossip Girl.

Whatever it is you know him from, I'm thrilled to have him with us here today to talk about his memoir, Brat: An '80s Story. Welcome, Andrew.

Andrew McCarthy: Thanks. Good to be here.

EDLC: So, let's start at the beginning. What inspired you to write this book and why did you decide to tell this story now?

AM: I suppose people have been, in one way or another, asking me if I would write it for 30-odd years since it happened. And my answer was always a very fast, "No," before the sentence was even gone. "Would you consider writing a book about the bra..." "No." Then a few years ago someone suggested to me, "Would you consider writing a book about the Brat Pack?" and my answer surprised me. I kind of went, "Huh. I wonder."

Anyway, I went off and I thought about it for six months or so, not really thought about it, just the idea percolated around. And then I just started to write it. I wanted to see if I actually had anything to say about it. So I wrote it, sort of, for myself, and then I took it out into the world after it was done.

"If you're going to ask someone for their time and listening, you need to come clean. If I want to understand it myself, I need to come clean with myself so I can understand what it was."

But why I wrote it now? I suppose I didn't write it a minute before I was able to, which doesn't say much about me, seeing it took me 30 years. But I think it was just a seminal moment in my life. It was such a thing that all of my life was affected by, those few years, and the label of being in the Brat Pack. And it so dictated the course of my life to some degree and cast a long shadow over much that I did. So much that I did. Most of what I did. We wouldn't be having this conversation if I hadn't been a member of the Brat Pack.

And I never looked at it. I always had my few stock responses…a few quick stories or whatever. But I thought I should look at that moment in my life and really look, see, what was under the rock…and why had I avoided it? And what did it have to teach me? Several years earlier I wrote a book about, a travel book, but it was really a book about coming to terms with getting married and the idea of how do we reconcile our craving of intimacy and our need to be alone. I learned a lot about myself in writing that and what my own needs were.

And so this was the same thing. I kind of go, "What did I have to learn from this?" That's why I wrote it. And I why I wrote it now is I didn't think I probably would've been able to be fully truthful with myself or the page or the listener in this case until now.

EDLC: Yeah, that makes sense. Speaking of your work, you're no stranger to narration. What was it like narrating Brat in your own words?

AM: At one point I was making so many mistakes the person I was working with asked me if I wrote the book. I assured him that I did. I find narrating difficult work. I think it goes back to when I was in grade school and we were forced to read out loud. I was such a fearful reader that I made mistakes and stumbled all over and felt stupid. Reading aloud, to this day, unless I'm reading to my kids at nighttime, I find somewhat intimidating.

Doing this book, it's interesting reading your own words. It's the second time I've read my own words, and I find it… I just wanted to get out of the way and tell the story. Talk to you. Talk to one person. I often think I write to my 15-year-old self. I think I just talk to myself when I'm reading because I wanted to feel very conversational and we are after dinner and we're finally going to just sit down and I'm going to tell you what it was like. I wanted it to be that kind of casual, and I didn't want to overarticulate and enunciate. I was working with the person and they said, "Well, can you enunciate a little more clearly?" And I said, "With all due respect, no. I don't want to enunciate. I want to talk to you, and if it's not clear or if I'm going too fast, which is my tendency, I'll be happy to slow down and try it again. But I don't want to articulate. I wanted to just talk to you."

EDLC: That makes sense. I know that in the early chapters, in your NYU days, you mimic one of your teachers. He's Greek. You mentioned him.

AM: Oh, Mikos, yeah. Before you even get any further, I have to say I usually cringe when it comes to funny voices and things, but Mikos, he had such a distinctive kind of nasal, eh! Neh!

EDLC: Yes.

AM: Oh my God. It was terrifying. Just even saying it now makes me just shudder in fear. I don't have good imitative skills, so usually the voices I try to leave to others.

EDLC: So within Brat, you recount your battle with alcoholism with frankness. In a recent interview with Publisher's Weekly, you said, "I don't think my acting success caused my alcoholism. Without that, I would have drunk cheaper vodka." Why did you want to tell listeners about your alcoholism?

AM: I thought if I was going to write this book about this period of time, there were three dominant factors that all were interrelated, and all affected each other, and one was my success. The other was the fact that I drank excessively. When I did the first draft, it was much more about just my work and, sort of, some internal emotional life, and I left out, largely, the drinking. Out of a sort of respect for my father, who’s passed, I left a lot of that out. And then I just thought, "Well, this is not the story. This is an incomplete story." And if you're going to ask someone for their time and listening, you need to come clean. If I want to understand it myself, I need to come clean with myself so I can understand what it was.

But very much my drinking in no way ever... People always want to associate drinking with, "Oh, well, you got successful too young and too fast and..." I'm like, "I'm sorry, no. I drank because I drank. I had an addictive problem with alcohol which was independent of my success in films." And I jokingly say, "Yes, of course I could drink better vodka because I was making money in movies." But my success wasn't caused by my drinking, and my drinking wasn't caused by my success.

Drinking is a primary thing in and of itself. Once I found the structure of making it about boom, the '80s, and making that a part of the story, that was a part of my story at that time.

EDLC: Right. And following on that, there's that specter of your father throughout Brat. And the listener can tell that this is a somewhat strained relationship that affected you deeply. The example of you handing over your first salary, for Class, to him, that was a poignant point for me in the book. In the book you say, "I was made very real and formidable by his request." That statement really struck me as very telling. What did you really mean by that?

AM: Money is a tangible thing, you know? I had no power in our home. My father was a very dominant and domineering person and force in my life. And that he had to kneel down and ask me for all my money, I know, cost him a lot. It made me… I was powerful. I then had what he wanted, in a very literal sense, and I bequeathed it to him out of the largess of me. It was more just, sort of, "You need it? Oh my God. Must be something really bad. Here, take it." You know, in my naivete.

It altered the dynamic of our relationship. Money is never just money. Money is power. Money is all sorts of things, and in that relationship, in that moment, it was power. It was affection from my mother. It was anything. It just altered who we were and how we related forever more. And then it just it went on. It proved to be very challenging for a time, and I didn't understand. What it made me feel was, sort of, unsafe in a certain way. At a point in my life when I would've really craved some kind of backup or support, I felt untethered. And when I tried to express that, those concerns were… My father, he was from a different generation and a different time, and he was a different kind of man than I was becoming. It caused a rift.

Now, he always used to say, "Were the situation reversed, I would give it to you." And without question I know he would've, and I did with him for a long time until I just realized this is not about money.

EDLC: Right. Let's talk a little bit about the Brat Pack. And speaking about the pack itself, how did you want to approach talking about the Brat Pack? What was the story you wanted to tell?

AM: The story I wanted to tell, I suppose, of the Brat Pack was the legacy of it. It was born in such a fraught moment, and it was born in this one article that was in New York Magazine that was very… It was a scathing indictment of a bunch of young actors. The writer coined this really clever, effective phrase. And the minute you hear it, you don't forget it. There it is, boom. We were branded instantly. Everyone tried to run from it. I certainly didn't like it when it first was leveled against us. For no other reason than the minute you're labeled and boxed, people stop trying to understand you. That's it. And in Hollywood, being boxed is never, or typecast in that way, never useful. Being termed a brat, it certainly isn’t a pejorative term in and of itself, although that was largely how Hollywood viewed it and how I viewed it.

"At a point in my life when I would've really craved some kind of backup or support, I felt untethered."

The general public seemed to just think it was fun and that just indicated a group of young actors who were in super-cool movies. And then it has evolved over the decades, and now decades that it is still commonly used in this affectionate iconic term of remembered youth. It's not so much my youth people are remembering. It's their youth. I'm sort of this avatar for who they were when they were young. That's what those movies represent now, is people's own youth. They project that onto it. So they're looking back, "the Brat Pack," with such affection now with these rose-colored glasses from their youth, when everyone was in their late teens or early 20s, when they were just cusping their own life and stepping out onto their own, and their future was a blank slate in front for them to be written upon. That's a thrilling, exciting time in life. There's no time that's more thrilling than that.

My son is 19 now and he is just blossoming, and it is just crazy. And he's just "Get outta my way, world." As it should be. I represented that and still represent that to people. I'll forever be 22 to that generation of people, which I guess I came to terms with the fact that that's a blessing, that I can give that to people to look back on their own lives and go, "Oh, man, those days." That's a real gift. And it took me 30-odd years to come to that.

EDLC: Actually, you answered my next question. It was going to be, when do you think that that moniker turned more nostalgic?

AM: Yeah, impossible to say. Once we all got old. You tell me when that happened. It's impossible to know really. It's just one of those... A cut that becomes a scar that becomes this thing that it just, and suddenly it's just there and you can't imagine life without it and it's part of you and it's all the good and the bad. It's all good and it all makes up where how you got where you are. So I don't… When did it happen? It's impossible to know, and that's the beauty of those kind of things. You just look up one day and it's like, "Oh. It's that."

EDLC: Right.

AM: I didn’t even know. It irritated and then it's transformed, you know, without my knowing.

EDLC: Going back a little further, back before Brat Pack. Your life between the release of Class and St. Elmo's Fire must've been really surreal. You lived for a bit with your costar Jacqueline Bisset and you hung out with the likes of Sammy and Liza. Looking back, what comes to your mind when you think of those episodes?

AM: Well, it's what they were, more as episodes as opposed to, like, living with and hanging out. I had encounters with Sammy and I did stay at Jacqueline Bisset's house for some time. What do I think? I think, "Oh my God. What a crazy.…" Again, when it's your own story it's like growing up in some weird family. People say, "What was it like growing up?" And you go, "I don't know. It was just my life. It seemed normal." But I have to say, even staying at Jacqueline Bisset's never seemed normal. I knew that that was not normal.

And going to Sammy's house was not normal. That was the wondrous part of it. There were many wondrous parts of all that time period where I was caught up in a whirl of wondrousness, and those were some of the nice highlights of it.

All those people were wonderful to me. So kind and gracious and generous, all the people that I met of that generation, the old Hollywood, were so kind and so welcoming into the fold as it were. I didn't understand any of that. I just knew that James Coburn, I met at some point, he couldn't have been more gracious to me, and Robert Redford, when I met him when I was a young kid, he went out of his way to be gracious and kind to me. I didn't ask why. I was just like, "Oh cool. My mom loves Robert Redford. This is cool. Like, Robert, he's a nice guy."

EDLC: You talk about their kindness a lot during that episode with the Paramount 75th anniversary photo that you were a part of. That part of the book was pretty fun to listen to.

One of my favorite movies of yours is Heaven Help Us. Even as early as Heaven Help Us, we listened to you in the book, you start to become interested in working behind the camera. What was the turning point for you to take on directing work?

AM: I did very early on become very interested in the technical parts. I always preferred hanging out with the crew than with the actors. And then I was acting on a television show, and a director fell out from one of the episodes. I was having lunch with the producer and he told right when we were having lunch, someone came up and said, "So-and-so dropped out of the next episode." And he went, "Oh no." And I looked across at him and said, "I'll do it." And he went, "Yeah, you probably could." And I went, "Yeah, yeah. I'll do it." And so I did, and it went well and then it took on a life of its own.

And then I found it suited my temperament probably in many ways a little bit better than acting did, in that I could apply all my skills without feeling the anxiety. I've often said that directing is stressful and acting causes anxiety. They're two different things.

EDLC: I could see that. In one of the early chapters of Brat, you mention a few of your NYU professors as we discussed earlier, but one really stands out, Terry Hayden. And listening to you speak of her inspired me to research her, and the first thing I found was her obituary in The New York Times. I was really impressed. I mean, she discovered James Dean. When did you know that Terry would be that force in you becoming a better actor and eventually a central figure in Brat?

AM: Terry was the only teacher I ever connected with. I was a terrible student in high school and I just escaped high school. She was the only teacher in my acting school that saw me in any way as having something to offer. So we would not be talking now if she didn't exist or say to me, "Hey you." You know? So I think teachers are an invaluable thing. It just takes one. And really, I had one teacher in my life who changed my life and it was her. She was not an easy figure. We were not close forever, but she was my teacher, and she put in the time for me over years and years and decades. She would come to plays I was in and see things I was in, and would be candid in a way, in the way she was. She was my teacher, and so a teacher is someone who tells you the truth and has your best interests at heart whether you like it or not. And there she was in my life. I owe her everything in that regard.

"It's not so much my youth people are remembering. It's their youth. I'm sort of this avatar for who they were when they were young."

I got to say that to her, at the end of her life by chance. I never do things like that. When I saw her going into her apartment, I went up and spoke to her. That was someone else in charge there. I would never do something like that. And yet I did and I’m very grateful that I had that opportunity.

EDLC: I thought it was a beautiful homage to her, really in the way you did that in the book.

I did a double take when you were speaking about Claude Chabrol and Quiet Days in Clichy because I had seen an earlier film of his, La Cérémonie, where I discovered Isabelle Huppert, and she's my favorite actress.

AM: Oh, God, fantastic. Right? Yes. She did a lot of films with Chabrol.

EDLC: Yeah.

AM: I'll tell you Isabelle's story. She came onto the set of Quiet Days and we were working and I loved her films. I loved the movie she did with Chabrol. So she came to the set, and Chabrol brought her over to me and then said, "Isabelle, this is Andrew. Andrew, this is Isabelle. Isabelle, Andrew, he is in love with you." And he turned and walked away. And I was like, "Oh, you bastard." And she just smiled at me and, yeah, very awkward few minutes. She's fantastic. But I love Chabrol. He was wonderful. He became a real father figure to me when I needed one. He was a wonderful man, and a brilliant filmmaker.

EDLC: Yes. I absolutely agree. I really like his films. You speak very fondly of him. Did you learn anything from him in terms of directing? What did you gain from him?

AM: He was just very intuitive, which is the way I've learned to be. He trusted his intuitiveness and he was very gracious. An extraordinarily gracious man, and inclusive to people. If any idea came along and it was a good one, he took it and said, "Oh, this is my idea now." He was mischievous and playful. He had a sense of delight about him because he loved making films, and he loved making them with his family. He loved eating and he had just a passion for life. I loved being exposed to that kind of spirit of enthusiasm for and passion for generosity. People that I saw as authority figures I hadn't experienced that way. So he let me know that that was possible to be that way in the world, and you get lovely results from work when you work that way.

But more importantly, he let me know that you can be that way in the world, without, of course, telling me anything. I just watched by his example. He included me and he embraced me, and it went a long way because I so admired him that he would embrace me and welcome me into his family and his, sort of, filmic world, like that was high praise.

EDLC: So you've continued to act and direct, right? Are you happier now behind the camera than in front of it these days?

AM: You know, grass is always greener, isn't it? I recently acted again. I direct a show called Good Girls, and so my friend, it’s a friend of mine’s show, she asked me if I wanted to do several episodes and act in it, and I did and it was really fun. I was surprised. I found out I hadn't really acted in about 10 years at least, and it was very effortless in a certain way. I felt I could be more with doing less. I had continued to evolve as a human being and I just hadn't been acting in that time. So it was interesting to realize how that plugged into acting. I was surprised how it didn't cause me much anxiety and that I enjoy it a lot, and I seemed to be able to access certain things I hadn't been able to access before. That was a nice little discovery.

I think writing the book also was very liberating to me in a certain way. I felt very much over the years imprisoned by my youth. To jettison it in a certain way was interesting. We'll see how that sifts out.

EDLC: Great. Andrew, thanks so much for taking time out to chat with us today.

AM: Oh, it's a pleasure. Thank you.

EDLC: To all our listeners, Brat: An '80s Story is available now on Audible. Thank you.