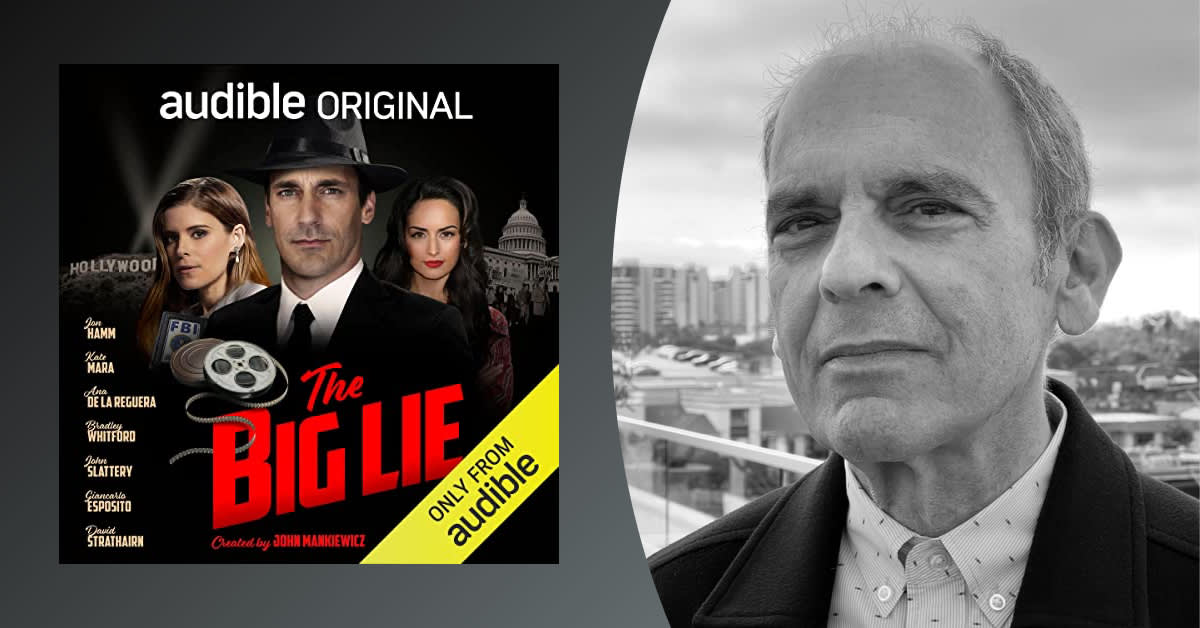

The Big Lie is an immersive, seven-part audio drama about the making of Salt of the Earth—the only movie named to the “Hollywood Blacklist”—and the FBI agent (played by Jon Hamm) who tried to shut it down. Series creator and executive producer John Mankiewicz talks about all that went into the making of this tour de force of audio storytelling.

Audible: As a film and TV writer and producer, what moved you to create The Big Lie as an audio drama series rather than for the screen?

John Mankiewicz: It started with a phone call from an old friend, Dub Cornett, who told me that his friend Jason Ross had just started a company called Fresh Produce, and Fresh Produce had a deal with Audible. Dub wondered if I had anything that would be good for an audio format. This was in early 2021, deep into the pandemic—the world had shut down. Like many people, my sense of isolation had pushed me away from visual media toward the calming, more intimate experience of podcasts, contemporary ones at first, and then I discovered these great old BBC radio plays by Samuel Beckett and Tom Stoppard, which really pulled me in. When Jason told me what Fresh Produce was doing—immersive, detailed narrative fiction—I immediately thought of The Big Lie. Every writer’s got a story in his back pocket that he’s never going to give up on. The Big Lie was mine.

What do you think makes this story especially compelling to tell now?

Propaganda isn’t new, and has always been used to create division. In the 1950s, Communism was “the big lie,” and the United States government said people like Paul Jarrico, Michael Wilson, and Herb Biberman were inserting propaganda designed to persuade patriotic Americans that Communism was the way to go into movies like Salt of the Earth. Now—and I mean right now, at this moment—“the big lie” for some in this country is that we have an illegitimate President of the United States, and America is once again divided. To me, that resonance is fierce and timely. As Churchill once said, “Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it.”

How did the writing and production process compare with bringing a story to screen?

Each is a highly collaborative process, but I’d say that for a couple of reasons I feel like the writer has more control with audio. Ironically, the rebirth of audio as a story delivery system feels newer and less set in its ways than film and television, certainly at the executive level at the production company, Fresh Produce, and at Audible, the studio or network. I felt like no one was trying to fit this story into a box; everyone I dealt with was concerned only with telling the best possible version.

“Every writer’s got a story in his back pocket that he’s never going to give up on. 'The Big Lie' was mine.”

One of the first big lessons I learned as a screenwriter was “show, don’t tell.” With audio, it’s the other way around—there are no dramatic close-ups to help you convey the meaning of dramatic scenes. You can’t just turn a 90-minute movie script into almost four hours of material overnight; it’s a completely different animal. I was lucky enough to have a wildly talented co-writer, Jamie Napoli, who understood the material and helped us navigate the audio world. Just for example, we needed a device that would move the story along, let listeners know where they were, both geographically and time-wise, and Jamie suggested using FBI agent Jack Bergin’s reports back to his bureau chief, which, of course, didn’t exist in the movie version. Bottom line: When you can’t show, you have to tell.

David Mansfield’s score just blew me away. Because there are seven episodes, and each one is slightly different in its emotional nature, David wrote seven different versions of the main theme. Extremely subtle differences, but important ones.

What was it like collaborating with voice talent, audio production, and sound design?

Even with the studio limitations of COVID, [director] Aaron [Lipstadt] knew he wanted to record Jon Hamm’s scenes with Kate Mara and with Ana de la Reguera together, so they could play off each other. Same with the three filmmakers and Lisa Edelstein, who plays Paul’s wife, and with Ana and Lela Loren, who plays Rosaura Reveultas. Other than that, everyone else recorded separately. Jamie and I zoomed in on all the recording sessions, and would text back and forth with Aaron during them. But when you’ve got such a strong director, a friend who’s been with this project since its inception, there’s not much to worry about.

Our audio production team was unbelievable, and kindly tolerated a very steep learning curve on my part. The idea of recording one side of a scene in June and the other in September terrified me. It’s hard enough getting a scene to work when the actors are together. But Peter Bawiec and Matt Schraeder made it all sound natural, added period specific detail—not just the sounds of '50s cars but the exact '50s cars specified in the scripts, everything. Joshua Paul Johnson edited all the dialog, and there was lots of it, and lots of takes, and he was somehow able to combine multiple takes of lines here and there to accommodate rewrites in post [production] and still make it all sound real.

What did you learn about audio storytelling, and what about the future of audio storytelling excites you the most?

The main thing I learned is that audio storytelling is really just telling stories to one person at a time—because the mix, everything about the sound, is designed to deliver the stories on headphones, which is truly an intimate experience. The headphones put each listener in a kind of private theater, absorbing the story in slightly different ways. But just like movies or television, if the performances, sound design, and music are done well, in an emotional and compelling way, the story you want to tell will come across.