Note: Text has been edited for clarity and will not match video exactly.

Audible: How did Born a Crime come about?

Trevor Noah: There were certain stories I just wanted to tell. I had stories from on stage, from life, from growing up in South Africa during apartheid — and from growing up post-apartheid with a father who was white and Swiss and a mother black and Xhosa. I wanted to tell a lot of these stories and, on stage, I was strangely limited within the confines of comedy. That is, the people need to laugh as much as possible.

Many times, I would tell friends and acquaintances these stories and they’d go, “Why don’t you share this with the world?” I was like, “But where? Where do you share it with the world?” One day, a good friend of mine said, “You should write a book.”

Initially it was just an idea of writing a collection of stories. It was just putting them together and seeing what came of it. I said, “I’ll write all the stories and I’ll see where it takes me.”

A: How did you ultimately decide on the narrative structure?

TN: I went through different phases. I thought, “Is it a memoir?” Then I thought, “I’m too young for that.” I thought, “Would it be a random collection of essays?” I came to realize, in the end, it essentially became almost like a love letter to my mom.

I grew up with her, I spent most of my time living with her. We were teammates, traveling through life together. It was this journey of new, constantly. That’s really what the narrative of the book became. It was our coming-of-age journey together for a mother and son.

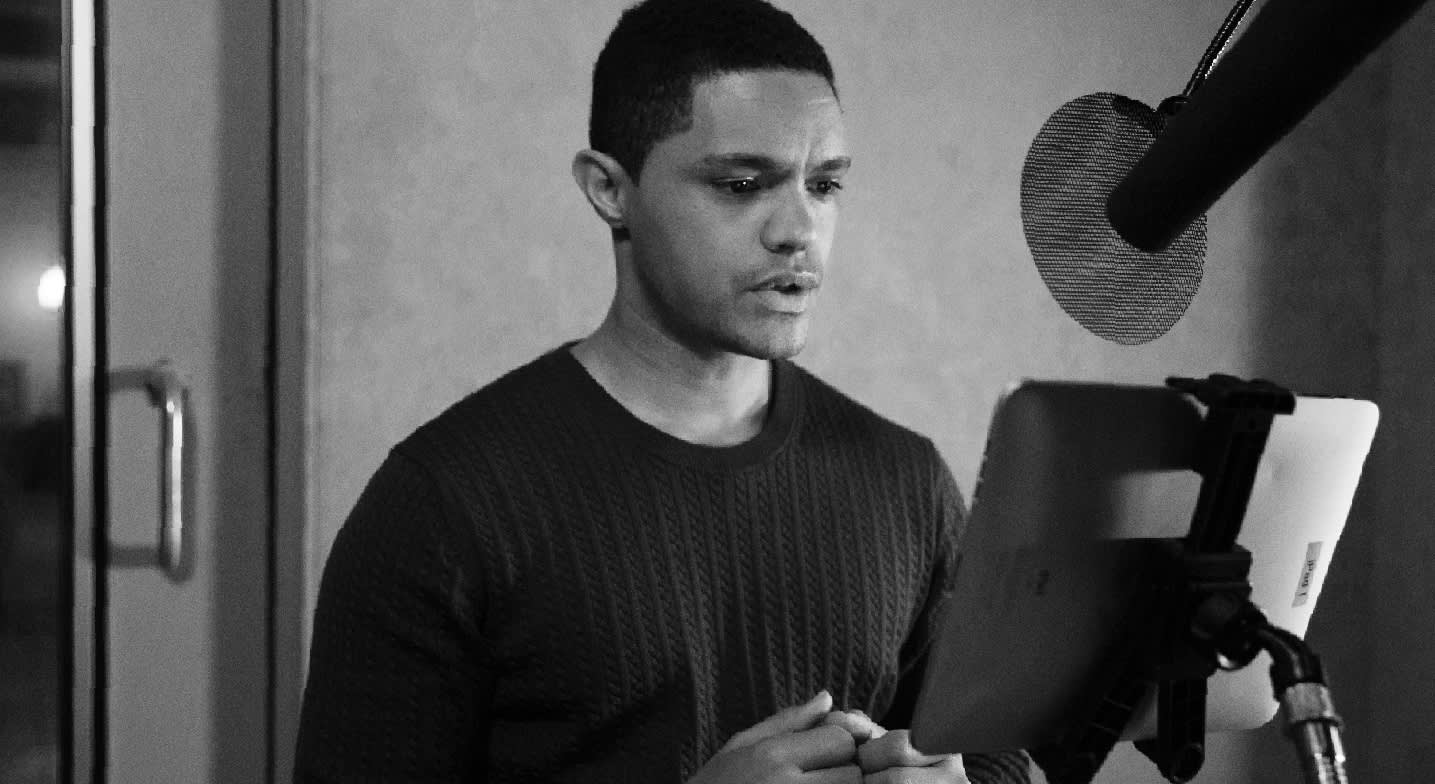

A: While writing, did you have the audiobook in mind?

TN: I think very early on I realized that I wanted to add an audiobook component, because as a comedian — as a performer — spoken word has always been my primary form of communication. If anything, the audiobook is more natural to me than the written book. That was a welcome addition to the process of writing my first book.

A: Did you know from the beginning that you wanted to narrate the audiobook?

TN: Yeah. I always wanted it to be me, you know? When I listen to an audiobook, I like to hear the voice of the author. Especially if it’s someone that I may know who exists beyond just the book. It’s nice to have that face and that voice and the idea. The most important thing for me was, when I tell the stories, I try and embody the characters.

The one thing that you get from the audiobook that you can’t get from the physical copy is the character. I love performing, I love doing voices, I love embodying my family members, my friends, people I encountered. So if anything, I always would have intended to read my own audiobook because it is, very literally, my own words.

I would read in the booth and go, “Man, how would Morgan Freeman do this?” If he could make penguins as human as he did, if he could make me engage with them the way he did, with that voice, imagine what he could do to my life story. I think that’s my goal for my next audiobook — to try to get to the place where I’m narrating it like Morgan Freeman.

A: As an entertainer, you’ve performed in a lot of different media. What’s unique about audiobooks?

TN: I’ve worked in radio, I’ve worked on television, and I’ve worked on stage. Each platform gives you a different set of tools to work with. The thing I noticed when reading the book was, because it’s an intimate experience, you’re not “performing” it per se. You are narrating it to a person. You are telling it to somebody one-on-one and you’re trying to engage the mind. That’s what I love when I listen to an audiobook: hearing the feeling of how a person is telling the story, them putting me in the place that I cannot be in because I’m not seeing the words myself.

A: How would you describe the difference between narrating Born a Crime and writing it?

TN: With writing, it’s the structure and making sure that your words, phrasing, and grammar are correct — it’s of the utmost importance for the written word. In terms of spoken, you have more parameters to play within. You have more spaces to exist within, because the ear can correct and play with what the eyes cannot.

When telling a story, because of feeling, a pause, when spoken, is very different to a pause on a page. A pause on a page has no measurement. Unlike music, you cannot measure how many notes the silence is meant to be held for. When you’re narrating, the pause is intentional. Every single moment is accentuated because you can apply that inflection or intention while you are narrating the book. That was definitely something that I enjoyed — I got to experience different highs and lows when narrating, as opposed to reading the book.

“In the specificity of our stories, we find the most common ground.”

A: So would you say it was more emotional — perhaps more cathartic?

TN: I think it was a lot more vivid. For me, less cathartic and a lot more engrossing. I felt like I was completely in the memory again. I felt like I was living it again and I was telling it for the first time, whereas when I was reading it, I remembered it. When I was narrating it, I was being it.

A: Why should people listen to Born A Crime?

TN: I would like for people to listen to Born a Crime because it’s a moment in time that I get to share with you, one-on-one. It’s a really intimate and special moment that can only be shared between a narrator and whoever is listening to the book. I would love for people to share that story with me.

Come into my world. Live in South Africa for a bit. Grow up as a mixed race child. Learn what it’s like to be an outsider in a world that is defined by only color and race.

It’s really an invitation; that’s what it is. I would like for people to come on that journey with me because I feel — this is what I learned when narrating the book and even when writing the book — in the specificity of our stories, we find the most common ground. That’s what I would love for people to join me on.

A: You’ve said that dreams are limited by the imagination. Could you explain that?

TN: I realized when narrating the book — when telling the stories again — how limited my dreams actually were. People often ask me, they go, “Did you ever dream of where you are now? Did you ever dream of what you’ve achieved?” The answer is no. My dream, honestly, was to live in a house that had a set of stairs, because I used to see that on TV and that looked fantastic. That you could throw a tantrum with your parents and then run up the stairs. That always looked fascinating to me. I always dreamed of having a house where I could look out onto something beautiful. Dreamed of having a fridge that always had food in it.

Those were the only things I ever wanted. That was the limitation of my life. Maybe a Ferrari was a thing because I could see it here or there. I was like, “That’s a dream. That is something worth having.” Anything beyond that, I was extremely limited by.

Your dreams are limited by your imagination. If you’ve been exposed to a certain amount of the world, then that’s the only place where your dreams can take you. If you’re a child that does not know about space in any way, you cannot dream of being an astronaut. It’s when you are exposed to all of these possibilities that your imagination can take you to the very limits of what you believe is possible through your dreams. That’s the greatest gift that my mother gave me — she may not have been able to give me access to the entire world, but she at least made me realize that the world existed.