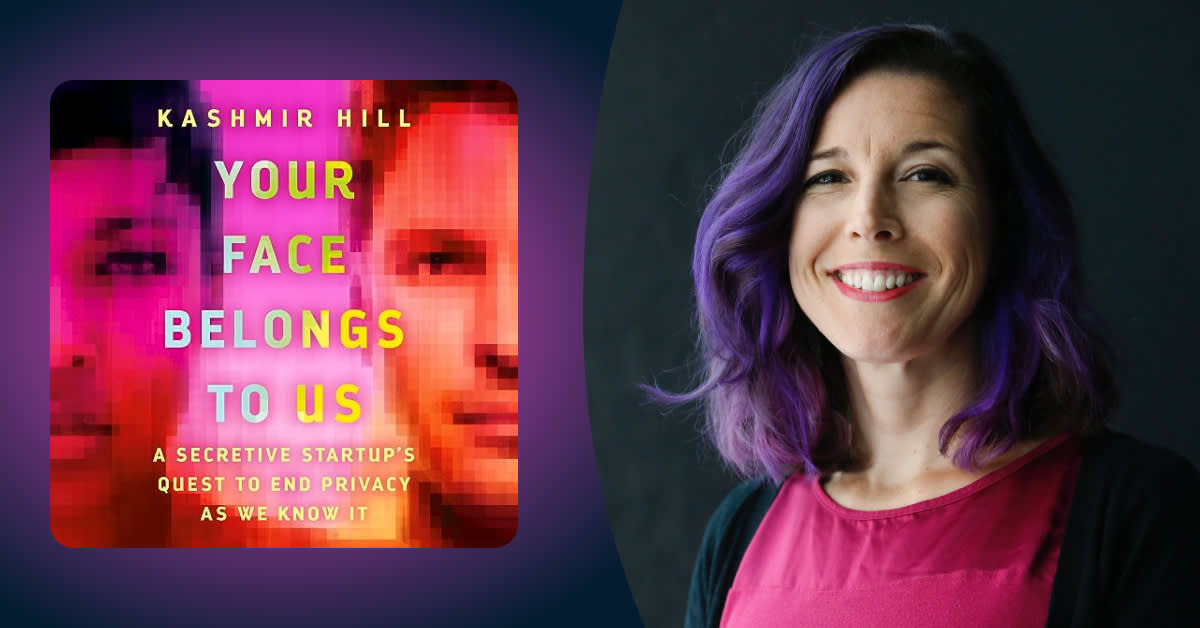

New York Times tech reporter Kashmir Hill tells the thrilling story of how one young Australian man built a controversial facial recognition app called Clearview AI in Your Face Belongs to Us. Here, we ask for her take on the ethical implications of personal identification technologies, the regulatory measures law enforcement and technology companies are taking to control its application, and the risks of overutilization. Plus, hear what Hill’s favorite listen of 2023 is (spoiler—it’s a fairy tale), and how it relates to her work.

Audible: The premise of Your Face Belongs to Us reads like science fiction—a tech startup sells facial recognition to law enforcement and upends privacy. As an accomplished tech reporter who understands the industry far better than most, what was your initial reaction to learning about Clearview AI’s actions?

Kashmir Hill: I was skeptical when I first heard what Clearview AI was advertising to law enforcement agencies—the ability to identify a person by face with something like 99% accuracy and find photos of them posted to social media websites and other parts of the public web. My skepticism grew when I tried to visit the office address that the company listed on its website, only to discover that the building did not exist. What Clearview AI said it could do was far beyond the kind of facial recognition technology that police had had access to previously, and even beyond what the most powerful companies in Silicon Valley had publicly released. But when I found police officers who had used the app, they sang its praises and said it was helping them solve cases in which a face was their only lead.

In Your Face Belongs to Us, you talk about how Facebook and Google created similar tech to Clearview AI and determined it was too unethical to release. Recently you’ve also written about how OpenAI stopped its test on integrating facial recognition into ChatGPT because of ethical and legal concerns, in spite of its benefits for visually impaired users. Conversely, some government and law enforcement agencies have been more than welcoming to the new tech. What are your opinions on this debate? Have we reached a point where facial recognition—and perhaps other technologies as well—need to be regulated based on ethical implications?

The power of artificial intelligence will mean that not just our faces will be searchable but also potentially our voices or even the unique way each of us walks. That will change how we find information about people in the same way that Google changed what could be discovered about someone in the early days of the internet, based solely on their name. Clearview is restricted to police use, but there are similar services offering the same superpower to anyone online, sometimes for free. That means, right now, someone in a bar or on a subway car could take your photo and find out who you are and see other photos of you that have been posted online. We are already seeing startling uses of facial recognition technology in the commercial context, such as at Madison Square Garden in New York; thousands of lawyers who work at firms that have sued the venue's parent company are barred from going to sporting events and shows there, turned away at the entrance when their face is matched to their photo from their firm's website, even if they have nothing to do with the case.

We have passed the point of needing to regulate it, and some places are already doing so. In some parts of the world, these uses would likely be illegal, such as in Europe under its strong privacy regime GDPR or in Illinois, under a unique state law protecting biometric information—the fascinating history of which I cover in the book. Laws have been successfully passed protecting people's face and voice prints, and they could be used to regulate companies that build these databases without people's consent. The question is whether more laws will be passed, and if they will be effectively enforced.

There is also the question of what we as a society want. Being able to search someone by face can be useful, not just for solving crimes but by the visually impaired, by investigative journalists, or by anyone who forgets a name at a cocktail party or work conference.

If so, what players do you think should be responsible for regulating technology?

Something that I found really interesting when I reported out the book was that the big tech companies have been effectively regulating the tech for the past decade. Google and Facebook had both developed Clearview-like tools internally, after buying up the early startups working on related tech, and then opted not to release the most radical version of the technology, deeming it too taboo. So it's really a combination of regulators paying attention to technological developments and acting accordingly, as well as companies making ethical decisions about what's worth developing and releasing to the public.

At what point does a project needs to be shut down?

I will leave that to the regulators to decide! In the case of Clearview, many privacy regulators around the world have declared that what the company did—gathering their citizens' photos without consent and creating faceprints from them—is illegal. They've ordered Clearview to delete their citizens' photos and a handful in Europe and the UK have issued sizable fines—the sum of which would likely bankrupt the company if it actually paid them. But enforcing these rulings against a company based outside of their countries has been tricky.

Who do you hope is listening to Your Face Belongs to Us, and what lessons do you hope they will take away from it?

That our faces can now be linked with our online dossiers is a seismic change in how we navigate the world. I hope anyone who will be impacted by this will listen to the book—people who have OnlyFans accounts under pseudonyms not realizing it can be linked to them via a photo; overpoliced communities who are more likely to be subject to facial recognition searches and potentially misidentified; and parents who want to prepare their children for a world where information may be organized around their faces and voices, so that any online photo or recording they post could be easily linked back to them in the future.

The book is written as a tech thriller—about how a young guy from Australia managed to go from building vacuous Facebook quizzes and iPhone games to gathering billions of our photos from the internet to make a radical, world-changing app. Within that tale is a lesson about the digital public commons, what we should put there, and who should have the right to use it. That is an extremely pressing question in the age of artificial intelligence programs, like ChatGPT, that learn from information scraped en masse from the internet.

How do you feel about the future of AI technology?

I hope we can harness the good and discourage the worst uses.

Last: what was your favorite thing you listened to in 2023 and why?

My favorite listen so far this year was Spinning Silver by Naomi Novik, exquisitely narrated by Lisa Flanagan. The producer I worked with on my own audiobook had done that one and said it was one of his favorites. I love fairy tales reimagined, and Flanagan was phenomenal at bringing each of the characters in that version of Rumpelstiltskin to life. It was also a fun listen because I compared one of the technologists in Your Face Belongs to Us to the fabled miller's daughter after he was ordered by Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg to complete the then-seemingly-impossible task of building a face recognition system that could differentiate between the faces of one million people. He did it—not by magic, but by mastering a new AI technique.