Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

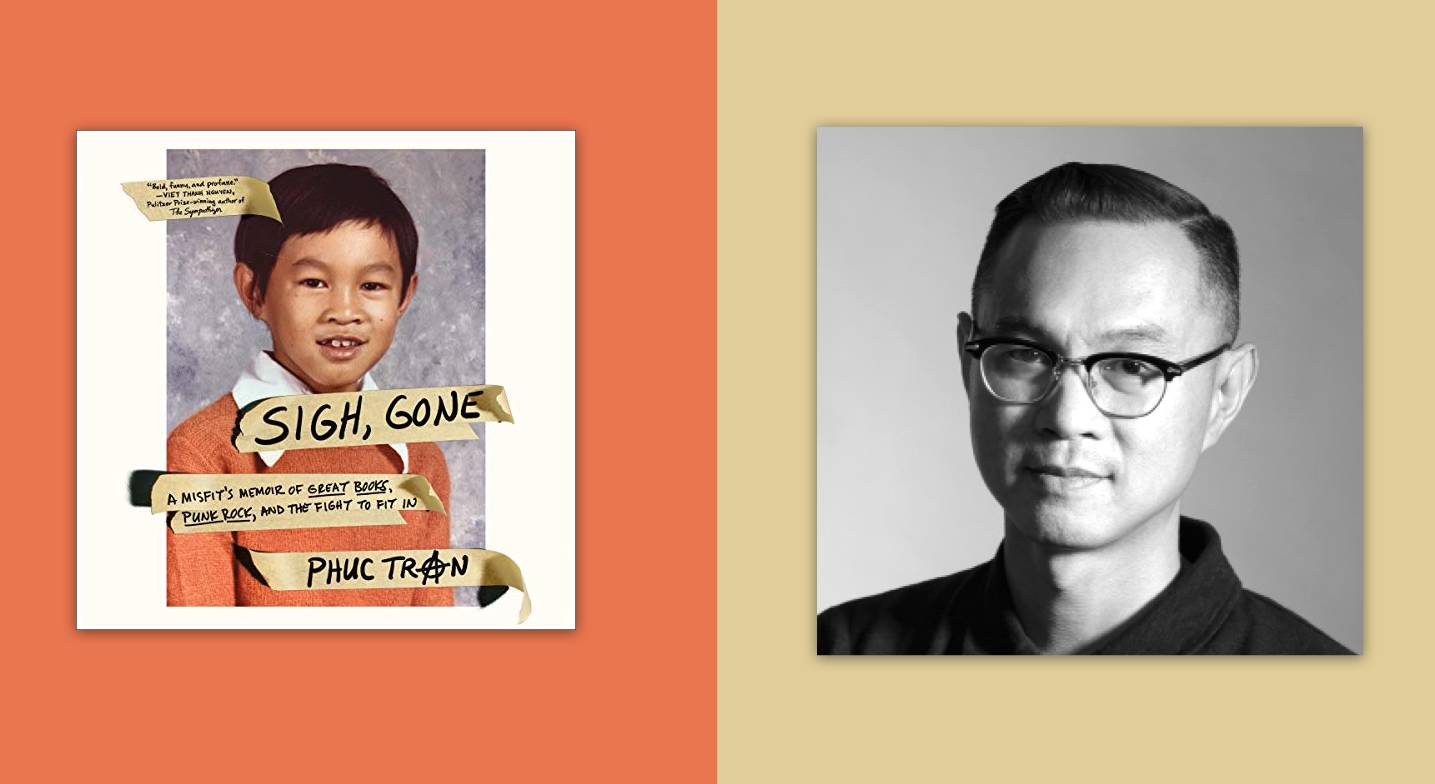

RSH: Hi, I'm Audible Editor Rachel Smalter Hall and I'm here with Phuc Tran, who is a high school Latin teacher and a tattooer in Portland, Maine. His debut book, Sigh, Gone, is a layered memoir about being a Vietnamese immigrant growing up in a small town in Pennsylvania, and it's one of my favorite listens of 2020 so far. Phuc, welcome to the conversation.

PT: Oh my gosh, thanks so much for having me.

RSH: So, I'm going to spring this on you right away. I want to play a clip from the opening of the very first chapter.

'Fuck that kid.' That’s what I thought when I first saw Hoàng Nguyễn in 11th grade. Hoàng never did anything to me, and he certainly never said anything to me. God, he hardly looked at me except when we passed in the hallways, me on my way to physics, him on his way to wherever. We’d glance at each other, give a quick nod, and move on, swept along in the rapids of our hallways. But fuck that kid.

Hoàng was a fun-house mirror’s rippling reflection of me, warped and wobbly. I hated it. I was Dorian Gray beholding his grotesque portrait in the attic, and I was filled with loathing. My disgust for Hoàng was complicated and simple at the same time: I was the Vietnamese kid at Carlisle Senior High School. Just me. Fuck that new Vietnamese kid.

RSH: So Phuc, did you always know you wanted to start your story here? Talk to us about how that played out to you.

PT: Well, yes and no. The prologue that is in the book actually was the thing that I wrote that secured me representation with my agent. In 2012 I gave a Tedx Talk, and maybe four years later—so in 2016—I was cold-called by an agent. Metaphorically cold-called by an agent in New York who sent me an email and said, "Hey, it seems like you have an interesting story to tell. Are you interested in writing a memoir?" And at the time, my younger daughter had just been born, and I had an older daughter, and I was working two jobs, so I was like, "I'm really busy." And so I ghosted her for a couple of months, and she politely kept pestering me.

And then finally one morning I got up and I just thought, "If I'm going to write my story, I really want to write it as authentically to myself as possible. Unapologetically. I'm not going to pull any punches." And the thought was, "I'm going to be as out there, and weird, and edgy as I am, and not smooth all the edges and try to please people." And so, that's what I wrote. The prologue is almost exactly what I sent Sarah [Lovett, his agent] in 2016, and I think my thought was that I wanted to take all the discrete Venn diagrams of who I was, right? My love of books, and the punk rock rebellious nature of who I am, and the refugee experience, and my love of Star Wars and pop culture, and I just wanted to smoosh it all into a document, and that's what came out of the prologue. And that actually ended up being my guidepost for writing the whole book. Even using the great books as lenses, that came out of just talking about Dorian Gray in that first bit. So, yes. I mean, it just came out of me and that's what it was.

I wanted my memoir to be messy, because I think that is what makes us, and our stories, everyone's stories, interesting. I didn't want to have it be nice and neat. I wanted to lay it all out there.

RSH: I was hooked from the moment I listened to that opening. One of my colleagues actually put your story on my radar. She knows I love memoir, and I’ve listened to the first minutes of many, many, many memoirs, and when I heard that, I was like, "Yes."

PT: Thanks for saying that. I've seen some people complain about the profanity, which I appreciate. I totally get it. It's not for everybody. I made this joke with somebody else, and I said, "I guess it's kind of like hot sauce, right? Or Sriracha. Any kind of spice." For some people, it's too spicy, but I think I was cooking for myself, so to speak, and I was like, "This is how spicy I'm going to make this thing."

RSH: I love that imagery of cooking for yourself. And that actually leads me to the next question I wanted to ask you, which is that, to me, your entire memoir feels like your answer to a question that I imagine you must've been getting your entire life, which is, why are you a Latin teacher and a tattooer? Or why do you love punk rock and classic literature? Do you think you were setting out to answer that once and for all?

PT: I love that question. Yeah, for sure. And not only that, but I've always been coming up against this idea of the false dichotomy of, if you like the one thing, you can't like the other. And obviously, when you're young... I see it in my kids all the time. They are very binary. I wanted to break the binary once and for all. Even to this day, if people are honest, sometimes they'll say things like, "Wow, you don't look like a Latin teacher." And that can encompass many things, right? It could be a racialized statement like, "I didn't think I'd ever meet a Vietnamese Latin teacher," or it could be like the tattoo thing. "Oh, you're so heavily tattooed. How could you possibly be teaching Latin?" And then, the flip side of it is I'll meet tattooers, and then they'll find out that I also teach Latin, and they're like, "What? What is that all about?"

You’re right. I think I'm just done trying to keep things apart and compartmentalizing things for the sake of not having a messy conversation, if that makes any sense. So, in so many ways, I wanted my memoir to be messy, because I think that is what makes us, and our stories, everyone's stories, interesting. I didn't want to have it be nice and neat. I wanted to lay it all out there. The complexity of it.

RSH: I agree. I think you did that too.

PT: Thanks.

RSH: You narrate your memoir, and as a narrator you come across as such a natural, and I wonder what that experience was like for you to narrate, and if you listened to other narrators to prep, or if you thought about how it would sound out loud as you were writing it.

PT: Thanks. Gosh, I am so flattered by that. The audiobook production process was so hard. Oh my god. It was so hard. And my agent, Sarah Lovett, tried to warn me. It was an off-the-cuff remark. She's like, "It's really hard." And I was like, "Oh, how hard could it be? I just wrote the book." But it was hard in a different way. My producer, Matie Argiropoulos, was amazing. She was really great, and super hands-on. I think maybe the best thing about prepping for the narration of the book was that I did a fair amount of live storytelling, Moth-style live storytelling events in Portland, and so I think I had a sense of the dramatic, and what I wanted out of it.

But other than that, much like the book, I just wanted to narrate it in a way that I would want to hear it. So yeah, but thank you. Thanks for enjoying the narration.

RSH: That live storytelling piece makes so much sense. And I've actually heard that from other people who aren't professional narrators but have narrated their live story, who I think have done a great job. They've said they had similar experiences.

So, I want to move on to Carlisle. Your hometown of Carlisle, Pennsylvania is almost its own character in the memoir. One of my colleagues graduated from Carlisle High a few years ahead of you, and she told me that she dated a few guys in the punk scene, actually. And she was so excited to listen to your book. But you're also really open about the difficult parts of being a Vietnamese immigrant punk kid in Carlisle, so I wonder if other people from Carlisle have been excited, or has it been hard for some of them?

PT: Wow. I would say that it has been pretty surprising for a lot of my friends, even my close punk rock and skateboard friends, because growing up in the '70s and the '80s, it just wasn't... I tried to avoid the conversation about race and my refugee background as much as possible, because naively and immaturely, I pinpointed all of my travails, and challenges, and conflicts to that fact, rather than thinking about, "Oh, we live in a racist culture, and my town is super white."

Instead of looking around me, I took responsibility for it and thought, "Well, these are the things that I can change," and so I didn't talk about it a lot. So they were really surprised at the internal turmoil that I was feeling at the time. Which is true for most teenagers, I think. You just want to put up this front that everything's fine and you don't want to talk about it. And it was the '80s and early '90s. Kids, I think, weren't as open to talking about their struggles as much. Nowadays, in a healthy way, kids are much more open to processing publicly the struggles of being a teenager.

And adults are taking it more seriously. In a lot of ways, our kids are stepping into a world of adolescence where we're more willing to take them seriously when they say things to us as parents like, "Hey, I'm really struggling with this thing." When I was growing up it was like, "Walk it off. Suck it up." What are feelings? Smoosh them down, deep down inside.

RSH: Yeah. From your friends who have told you that they've been surprised, has anyone reached out to you to try to talk about what that period was like for you?

PT: A little bit. I'm so deeply touched by the number of fellow high school classmates who have shared their own struggles. I'm so deeply humbled by that outpouring of sharing of their own story. One of my motivations in writing my own story is an invitation for all of us to hear each other's stories. We don't do it enough, and I don't think we do it in a deep and sincere way. It did, and it still does feel so incredibly powerful for me to tell my own story, and to have people respond to it in the way that they have, and it's been healing. It's not going to make the world a worse place if we could do that for each other.

Kids have reached out and said, "I grew up in a house with alcoholic parents," or [there have been] kids who were super closeted in high school and they're just telling me how terrible it was for them too. I, naively, also assumed everybody was having a better life than I was. Right? That's the nature of being a teenager. And it's been incredible to hear that piece of it. It’s been such a learning process for me to be like, "Holy smokes. All these kids were going through all these things as well."

RSH: One of the things I really appreciated in your story is how you share your awakening to the realities of racism. And you do that through this series of events that culminates in a college admissions interview. Why was it important to you to share this particular story?

PT: One, I wanted to talk about or revisit how naive I was as a kid. It feels pointed now, and obviously, when I started writing the book four years ago, it's hard to predict where you're going to be, the country's going to be, never mind yourself and everything else. It's so easy to have this cartoonish idea of who the bad guy is, or what a racist looks like. There's this whole episode in the book about how my brother and I think that racists are basically just Nazi skinheads in the punk scene, and we have to fight them. And then, once we beat up the Nazis, well then, we've vanquished racism, like this World War II template. But it's not that easy.

I relay these ideas of, who are all the people in power, and all the ways that they exhibit overt or covert racism? Including people in my family, and including myself. There's internalized racism, there's the systemic racism, there's the racism of people who are in power, and it's an indictment. I don't know if it's a soft indictment, but it's certainly a reckoning, and again, an invitation for us to all think about how we're all complicit in maintaining that power structure, right?

RSH: Yeah.

PT: The racist power structure.

RSH: I was struck how you talk about how you compartmentalized the racism at first, and you talk about how these microaggressions that you experienced, you categorized as anti-Vietnamese, or anti-immigrant. And so I was wondering if, for those who haven't listened to your memoir yet, if you could share a little bit about that college admissions interview, and what happened afterward, and how that really informed your awakening to what has always been happening all around you.

PT: Yeah, sure. Internal to my family, I think any time that my parents experienced bigotry or racist remarks about, "Go back to your own country," or being called all sorts of racial epithets, I think my parents always... I mean, they heard it and they understood what it was, but they never assigned it to racism, capital R or lowercase r. They assigned it to, "Oh, we're living in the shadow of this war that's long and painful for this country, and people hate us because we're Vietnamese." And also, in school, you learn about the civil rights movement and racism in this country, and it's portrayed in, literally, this black and white binary, right? This conflict. And so, I didn't understand that I also fit into that puzzle in some way. There certainly wasn't any conversation about it; I don't solve anything in my memoir. It's really just about talking about understanding my not being white, or my being... I think some educators would say that being Asian is white adjacent. I'm complicit in it, in some ways. And what's tricky is understanding that I'm also a cog in that machinery.

Once I realized that I needed to stop asking my parents to be people they couldn't be, and vice versa, we've come to an understanding that they have a limit or a threshold to who they can be as parents to me, and I'm okay with that now.

So what happened was I went to a college interview and I talk about how much I love literature, and the universal values of literature, and the college interviewer looked over my essay, and looked at my transcript, and he basically just said that I did really well, but it's to be expected for Asian students. And I thought, "Wait, what?" I couldn't even... I just had never even thought of... There were no Asian students at my school, so I didn't even have that mindset of, "Oh, Asian kids are grade grabbers and get straight A's." I was like, "Wait, what are you talking about?" That really caught me off guard because I had never even heard of that stereotype. And then he basically made these strange comments about [how] he thought that my love of literature was this angle that I was playing or that I was positioning myself to be not a future engineer, or lawyer, or doctor or whatever.

It was so strange, and I was really disheartened by that. It's like the first time you realize that the meritocracy is not a meritocracy, right? That hard work and getting good grades isn't all it's cracked up to be. That there's another system in play. It was really eye-opening. It's like learning there's no Santa. You're like, "Wait, what do you mean there's no meritocracy? What do you mean the kids who do the best don't get in?" It was disheartening, for sure.

RSH: And the subtext there, if I'm understanding right, is that he almost was devaluing your accomplishments, because it was good, but maybe not good enough for an Asian student.

PT: Totally. He literally was like, "Yeah, but it's what I expect from Asian kids."

RSH: Yeah.

PT: And I was like, "Wait, what? I worked super hard. What do you mean this is 'par for,'?"... You think that you just won the game, and he's like, "No, it was par." And I was like, "Come on." It just was very frustrating.

RSH: So, you touched on this briefly, and I wonder if I could get you to talk a little bit more about it. There is that scene with you and your brother and the punching Nazis. And the way you relay it is, it's told with such heart and humor, even though it's a difficult subject. You go on this journey through the punk scene in 1980s Pennsylvania, and I was fascinated by your discussion of skinheads and its origins in Great Britain, and so I'm wondering if you could elaborate on that a little bit, and what you hope listeners will take away from those passages.

PT: Oh my gosh, sure. In the '80s, for a minute, Nazi skinheads, they were the bogeymen of the punk scene, and so we were just always so terrified of... I mean, they were a physical manifestation of white supremacy in the most cartoonish way possible. They were these foot soldiers to the whole white power movement. But then, we met some other skinheads, nonracist skinheads who told us all about how the skinhead movement was originally a working-class movement, and it was multiracial. It was about poor white working-class kids and then poor black English youth coming together. And as many things are in England, it was a class thing. So, it was working-class kids versus bougie kids.

And so, they had this whole skinhead movement in the late '60s and '70s. And then, in the late '70s, when the English right-wing national front scene emerged, they co-opted the skinhead movement. And obviously, it's this, who gets the bad press? Right? It's the 1% of skinheads who are racist or right wing. They've taken over that narrative, for better or worse. Then in the U.S., there's still a pretty robust skinhead movement. And traditional skinhead. They have to always identify themselves as nonracist skinheads, as if the default of skinheads were racists skinheads. And so, it's unfortunate, but they're out there, for sure...

RSH: Well, I was very fascinated by your recollections of that punk scene. We won't get into it too much here, but—I want to call it "mischief"—the incidents that you and your friends got into when there were some clashes with the police? I was really fascinated by those passages.

PT: Oh, thanks. It's just small-town shenanigans, right? Just kids being teenagers who have a long summer in front of them with not a lot to do.

RSH: I'm familiar with that from the town I grew up in. I want to move into, to wrap things up, I was very touched by your portrayal of your parents, and I think your memoir shows them a lot of compassion for the struggles that they must've gone through as immigrants. You talk about how their careers completely changed, and their lifestyle completely changed after becoming immigrants. But eventually, you reveal troubling incidents, like the time you brought home a report card that didn't have straight A's, and your dad was so angry that he literally tried to stab you with scissors. How did you make these difficult decisions about how to portray your family?

PT: Thanks. It was really hard, but looping back to what we were saying earlier about wanting to portray my story in as complex and as messy of a way as I could, just to honor it, right? And to give it voice, and to recognize that it's part of who I am. Writing the book was an incredible process for me. And also, let me back up. Big shout-out to therapy. It's not like I just woke up one day as a middle-aged man and was like, "Oh, I really empathize with and humanize my parents in a big way." There was a lot of, 10 years ago, lots of counseling and working through some hard issues. In writing the book, a great charge from my editor and my agent at Flatiron was that it was important for me to humanize my parents, which I think I was going to do anyway, but the idea that writing their stories, and writing about them as, quote-unquote, characters in my book, really helped me empathize with their struggle in a long and slow way. Because I think writing and reading, technologically, it's about as slow as it gets, right? And so it let me really sit with those ideas.

I think about this quote from Oscar Wilde about selfishness. Oscar Wilde says that, "Selfishness isn't living your life how you want to live, it's asking other people to live how you want them to live." Once I realized that I needed to stop asking my parents to be people they couldn't be, and vice versa, we've come to an understanding that they have a limit or a threshold to who they can be as parents to me, and I'm okay with that now. And also, no, I can't be the dutiful, pious son that they expect of me, because it's just not who I am. And somehow, we can still be there for each other, to the best of our abilities.

RSH: Have they read the book? Or will they, do you think?

PT: They have not read the book yet. They've bought it, and my dad sent me a text and just said, "Looking for some quiet time to read it." My mother is functionally illiterate, so I don't think she's going to get it. I mean, I just don't think she's got the capacity to read it. And this is not a judgment. I think my parents, they're very black-and-white thinking. They're not going to see the complexity that I think you recognize in my telling of it. They're going to see it and I think they're going to feel embarrassed about it. But I tried to be careful. I only told the stories that needed to be told, but I told them truthfully. So, I'll let you know. I'll let you know what they think of it.

RSH: Please do. Phuc, thank you so much for giving us Sigh, Gone, and thank you for talking to me. For those of you listening, Sigh, Gone is available now on Audible.com and in the Audible app.

PT: Thank you so much for having me, Rachel, it's a delight to talk.