Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

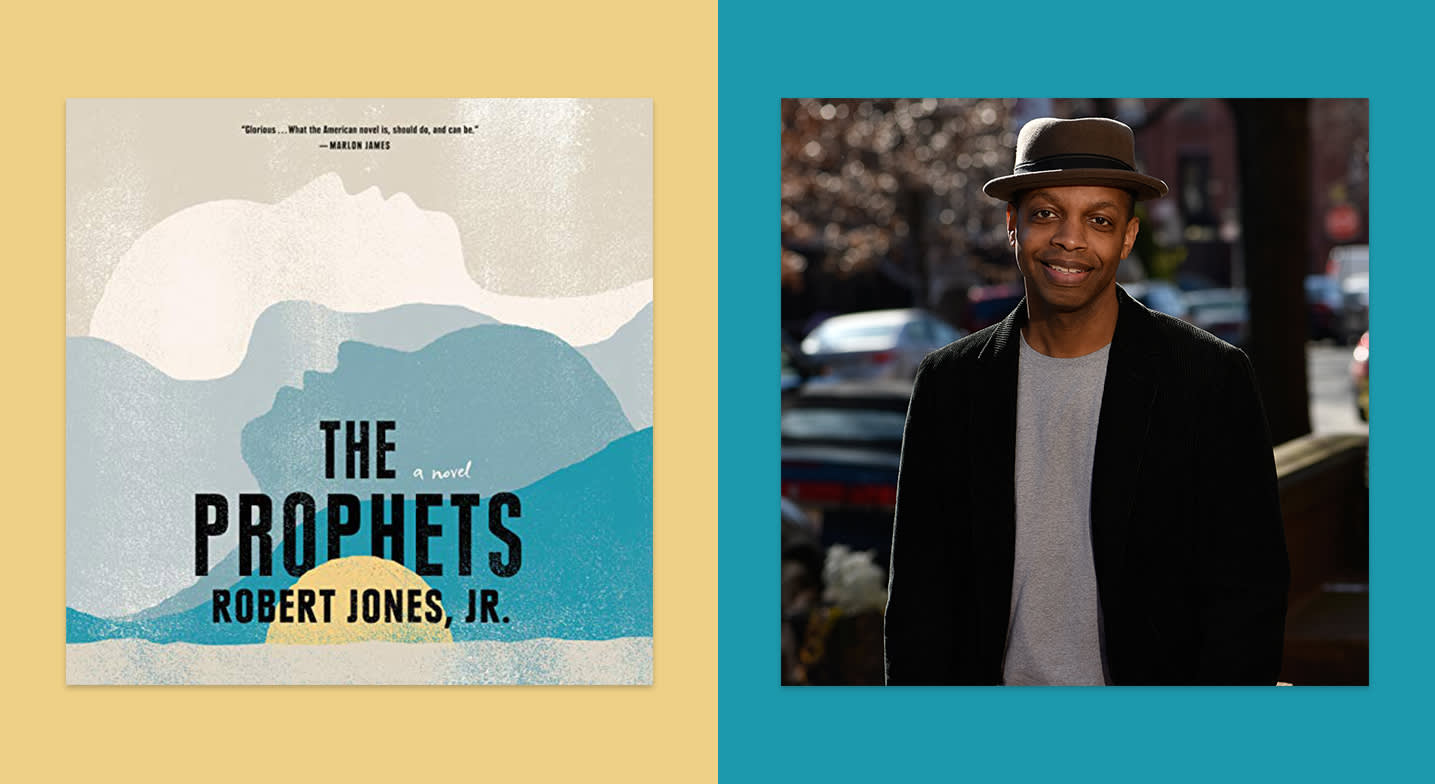

Tricia Ford: Hello, everyone. This is Audible Editor Tricia. And here with me today is writer Robert Jones, Jr. author of The Prophets, which is his debut novel, and what I would like to call an astounding example of historical fiction. Thank you so much for joining me today, Robert.

Robert Jones, Jr.: Thank you so much for having me. It's a pleasure to be here.

TF: Now, at its heart, The Prophets is a love story, complete with the couple whose names will forever ring together in my mind, Samuel and Isaiah, Isaiah and Samuel. But it's not a simple love story. It's a story equally defined by the historical context of their lives as two enslaved young men on a cotton plantation in antebellum Mississippi. So, Robert, with that opening, I think I'd like to start with this time and place and ask you, what made you choose this?

RJ: You know, as an undergrad at Brooklyn College, my minor was Africana Studies. My major was creative writing. And I was completely caught up, and, enamored with the writings of Black scholars and Black authors talking about Black topics. And it struck me as a little bit odd that prior to the Harlem Renaissance, we don't see any mention or any discussion of people who live at the intersection of Blackness and queerness.

"Everything for me begins with character. Character drove almost every single choice I made."

And the first encounter I ever have with it in literature is Wallace Thurman, who was writing during the Harlem Renaissance in 1929. He wrote a book called The Blacker the Berry, where there is some mention of, the, that intersection that I'm speaking of. And then, of course, later on, we have luminaries like James Baldwin. But prior to that, there's nothing, at least nothing I could find. So I attempted to do some research, and I went looking high and low, and could only find two examples of anything that came remotely close to what I was looking for. In Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Jacobs, which is a slave narrative, Jacobs talks about how a plantation owner, her master, or a friend of her master's, a white person, raped a male slave. And then in Toni Morrison's Beloved, there's a scene in which one of the characters, Paul D, is sexually assaulted by a male overseer. So I thought, "Okay, but what about love?" And that started me on the journey to writing The Prophets, because as Morrison herself said, if you cannot find the book you wish to read, then you must write it. And so in 2006 in my first semester of grad school, I started writing what would eventually become The Prophets.

TF: Wow. So it's been a long journey that you've had with this book.

RJ: From the moment I picked up a pen to the moment I put down the pen, was 14 years.

TF: Amazing. That is an amazing accomplishment. And I know you're an accomplished writer in other means as well. Can you speak to your other writing life a little bit?

RJ: Yeah, I created a social justice, social media platform called Son of Baldwin, which was my tribute and homage to James Baldwin. I was exposed to him in undergraduate school and became obsessed with him because I saw in him a kindred spirit. He was Black. He was queer. He was a writer. He was born and raised in New York City. And I thought of him as my spiritual godfather. I went and did so much reading about him, and about his work, and I read everything I could possibly find that he had written, and thought, "Why isn't this individual greeted with more acclaim? Why isn't he being taught in every single class?"

TF: Right.

RJ: And I said, "Well, maybe we can start this conversation." And I started Son of Baldwin in which we have these political discussions, sort of as an answer to the call that James Baldwin's brother in a documentary said it was one of James Baldwin's final requests that we find him in the wreckage. And so I went about finding him in the wreckage, and we had these conversations, and it kind of grew from there. As a result of that platform, I had the opportunity to write for Essence magazine, and The New York Times, and The Paris Review. So it's been quite a wonderful journey.

TF: That's an amazing thing. And I've read through a lot of your articles and essays, and they are brilliant, and so different than fiction. And I know you spoke to a little bit of Toni Morrison's influence and how she said, if you can't find your story to write the story.

RJ: Right.

TF: You said it much more eloquently than I did, as did Toni. But just talk to me a little bit about where these characters came from. I know you mentioned research, but are they built on real people in your life? And how is that intersection between historical accuracy through research, and, I guess, human accuracy and their experience, and as you said, in this loving relationship that you created?

RJ: You know, writing The Prophets was probably one of the most daunting tasks I've ever took on, and I was not confident that I would be able to tell this story. In my first semester of grad school, what kind of confirmed for me that this was the story that I was called upon to write was that my fiction tutorial instructor, Stacy D'Erasmo, gave us an assignment. She said, "Go out into the world and find objects that a character or a story that you're thinking about would possess." So I was walking along a street in Brooklyn one day and found a pair of shackles. Goodness knows what these shackles were doing lying on the curb near the garbage, but I saw them and was immediately struck by them, picked them up and felt the weight of it and said to myself, "This character's enslaved and I want to write about a Black queer character prior to the Harlem Renaissance. Don't tell me I'm going to have to write about a Black queer character in antebellum slavery when there is nothing of the sort in the record, how am I going to do this?" So I started sketching it out, starting with the character that would eventually become Samuel. Just how he came to be enslaved, what his favorite foods were, what he smelled like, what he looked like, what he loved, what he hated. And from that, I began to build him, and then build a world around him. And initially, the book was only going to be told from Samuel's point of view. And then I realized that Samuel's point of view was not enough. It wasn't giving me what I needed to sort of build the world that I wanted to build.

And so I said, "Okay, his love interest will also have a voice in this." And that still wasn't enough. And I realized that the reason why it wasn't enough was because the real heart of this story was the love between Samuel and Isaiah, and that love needed witnesses. And so I began to give life to the other characters around them, as well as to Samuel and Isaiah, to sort of give the story more dimension and more life. And, of course, this required a tremendous amount of research on my part, to not only understand that period of time, that gruesome period in American history, but also to understand a period of time prior to that, because the novel not only discusses antebellum slavery, it also goes back to pre-colonial African societies to take a look at how Black people functioned prior to European interference.

So I get this interesting contrast of what things like race and gender and sexuality and gender identity looked like in early Western constructions, but also in pre-Western constructions, and that was a lot of research, the most interesting of which was the oral histories, where I found the most rich and detailed aspects of the story.

TF: The introduction of bringing that oral history or the gods of Africa into the story, and the construction of how you put your story together, are my favorite parts of the book. I know each of your chapters is told from different perspectives, mostly of different characters, but interspersed are these chapters narrated by the gods of Africa, and they are serving as witness to the experience of their descendants. And I just thought it was a brilliant use of that. And it's also where I found your choice of narrator in Karen Chilton as brilliant! She was brilliant when performing the African gods and brilliant in your "regular" chapters told by the real-life people in your story. I'd love to hear more about the structure and how you decided which characters deserved their own chapters.

RJ: That's really interesting. Everything for me begins with character. Character drove almost every single choice I made, whether it was which characters get to speak, whether it was how this novel is structured and told. Everything was driven by diving into who an individual character was and who they encountered, it was almost like, "Okay, so now, Samuel has met Maggie. And so Maggie now has a story to tell because she has a slightly different perspective about things that go on this plantation because she's been here longer. So now she needs to speak." And that is sort of how I decided which characters got to talk and which characters were minor, if at all. And in terms of the ancestral voice that comes in to kind of give their perspective and their wisdom, that came to me actually in a dream.

"When it came to Karen Chilton, something in my gut quivered when I heard her voice, and the hairs on the back of my neck stood up. And I said, "It is her. Can we please have Karen Chilton?""

I keep a notepad and a pen by my bed just in case inspiration strikes in the middle of the night, and I woke up from this dream, and I scribbled something down into the dark and went right back to sleep, not even remembering what I scribbled down in my chicken scratch handwriting because I couldn't see. When I woke up in the morning and took my pad to my home office and put it down preparing to enter whatever it was that I wrote into the manuscript, I read it aloud, and it said, "You do not yet know us." And I said, "That's a direct address. Who is that talking to? And where does that even fit in this novel?" And I thought, are these the ancestors telling me that they deserve a voice in this, and that they need to interrupt the narrative, so to speak?

So I began to write from the ancestral voice, and they actually led me back to the continent. Because another line that eventually came to me was, "This is not the beginning, but this is where we shall begin." And I thought, well, where? Where shall we begin? And I thought, and I thought, and I was like, "Oh, I think this voice is saying, not here in, during antebellum slavery, but a before time," so that we can understand, not only our own cultural traditions before European interference, but how we looked at love before European interference. And that is how the African chapters came to life. And then to go back to Karen Chilton, the reason why I needed to have Karen Chilton narrate this book, is because when I hear the voices of this book, when I heard the ancestral voices in particular, it was the voice of a Black woman, of a particular tone and timbre, and I listened to about a dozen voices, Phylicia Rashād, C. C. H. Pounder, but, and they were great, they were absolutely phenomenal. But when it came to Karen Chilton, something in my gut quivered when I heard her voice, and the hairs on the back of my neck stood up. And I said, "It is her. Can we please have Karen Chilton?"

TF: I love that.

RJ: [I was] fortunate enough, for her to say yes. I haven't listened to the whole book yet because every time I hear her voice, I tear up. So I've been, I've been listening to bits and pieces. My mother, however, has listened to it at least three times already. And she said, "I don't know who this woman is, but she was the perfect choice."

TF: She really was. It struck me immediately in listening, but then it strikes you even more when the ancestral voices come in. It was a wow moment for audio for sure, and just speaks so well and so strongly to, you know, the heritage that that was born out of, and how it came through her, the way your words come through you. It was just a perfect little symphony and a perfect collaboration, for sure.

RJ: Thank you.

TF: I did find your female characters very, very strong, and I was curious about that female voice and the choice of the female voice, and you explain that beautifully. I just think it was another brilliant and not obvious choice to have a female narrator.

RJ: It was. First of all, I owe a great debt to Black women, the ones that I'm related to, my grandmother, my great-great grandmother, all of the line of women that I come from, were all very strong and also very vulnerable, and very full women, who, for the most part taught me how to claim myself, for myself. And not to mention that, I think that Black women writers are likely the best writers on the planet, and so, in a way, I was paying tribute to Black womanhood by ensuring that Black women had a part in this narrative, that I rendered their voices as authentically as I possibly could within my power and research, and that Black women were not erased as they are so often from this kind of narrative and from this kind of story, or at least they're made secondary.

"I think that Black women writers are likely the best writers on the planet."

I wanted to ensure that Black women in particular, were represented powerfully within this narrative, and I tried my best, I really tried my best to give Black women a voice and character and dimension and differences, because they're not all the same women. They make up a community, but they are all distinct. And I really, really wanted to just sort of as a tribute to my grandmothers, Corrine and Ruby, include some women in this narrative that kind of showed the integral role that Black women played in history, not just Black history, but in history immemorial.

TF: Amazing. I think you succeed in that very, very well. And little bit of the cherry on top, so to speak, is your choice of narrator there, just another little gift to that huge respect that you give women in your life and in history.

RJ: Thank you.

TF: Now, I'm curious about whether or not—I know you mentioned that you've listened to parts of the book, but not fully through—do you listen to other people's novels? Or are you a big podcast listener? What are your listening habits?

RJ: You know what? NPR shaped me. NPR has been doing podcasts for like decades, but we just didn't call them podcasts always. So This American Life is, I think, my introduction to what we understand as a podcast. And there's something really phenomenal about audio without visual, in that it allows you, much like reading does, to create the world yourself so that when the narrator or the person speaking is giving you the details or leaving out some of the details, you're filling them in. So it's a conversation, even though you're not really talking directly to the person in the same way that reading is a conversation. It's the writer and the reader going back and forth. It's the same with podcasts and audio—you are in conversation with that person. And you're coloring in the outlines that they're creating, and it's just wonderful.

I love to listen to Toni Morrison's audio. She narrates her own stuff, and she speaks with... You just imagine that, "Oh, this is just the wise woman of the community speaking," when you hear her voice. It's so soft and tender, and yet when she gets to particular verbs, she, boom, she, announces them with such verbs, and so you feel the word. It's onomatopoeia, you feel it, that what's she's saying, and it's just like, how powerful is that? Like, it's just so wonderful. And I also got to listen to Adam Lazarre-White, who's an actor. He does the narration for James Baldwin's Go Tell It on the Mountain. He has such a powerful voice. It's almost like, and this might be a bit blasphemous to say, he almost sounds like what God would sound like, you know? If God were a man, because I'm not clear on the fact that God is a man. But if God were a man and had a male voice, it would be Adam Lazarre-White. Who I hope narrates my next book. I really do.

TF: Oh. Now is that something that is in the works currently, your next book?

RJ: You know, I am about 40 pages into the next novel, and I had to stop because my world is now 127% The Prophets. And so, I don't have the creative well to return to the second novel. I'm just really focused and concentrating on The Prophets for promotional purposes and such. But once I return to that, I'm going to go full gusto with the second novel. In my head, I hear a voice that's like Adam Lazarre-White's when I write that book, and so hopefully he's available.

TF: That would be amazing. And I think it's amazing that you have a narrator in mind when you're 40 pages into writing it. Absolutely love that, because it will inspire the next 200 odd pages that will be coming out of you.

RJ: From your lips.

TF: One thing that I almost don't want to bring up, because I don't think it's in the audio, but are the acknowledgments at the end of The Prophets. I'd love for you to speak to just the huge amount of credit you give to so many people around you, from artists that inspire you to people in your daily life supporting you. What made you write such an extensive acknowledgment?

RJ: You know, the honest truth is that I said to myself, "What if this is the first and last thing you ever write?" Because who knows what reason, something happens to you, whatever. You have the responsibility to thank every single person in your life who has inspired you, encouraged you, supported you in some way on this journey, who said to you, "You can do it," that it is not some pipe dream, that it is something that you can make manifest if you put in the work.

"...The most important thing to me in that book is love."

And so I set about thinking about who has ever inspired me, who has ever supported me, who has ever said to me, "Robert, you can do this." And I proceeded to thank them. Even the people that I don't know, like Janet Jackson, for example. Or people who I haven't seen in a very long time, like my fourth grade teacher, Mr. Firestone, who was the first person that I can remember that told me that I was a good writer. I felt a huge responsibility to do that. And when I look at that acknowledgement section, which is pages and pages and pages, which some people have said is its own chapter, I think, "God, who did I leave out?" I feel terrible when I come across and I look for a name and I'm like, "Oh, my God, I didn't put this person in. Oh, how could I forget?"

TF: Well, that will spur you on to writing the next. They can head up the next acknowledgment section.

RJ: That is what other people have said, and you're absolutely right. I have to start writing down the names that I forgot, so that I don't forget to put them in the next one.

TF: I do think it speaks so well to your underlying or overlying message of the story where, you know, it comes down to, it's about love. And it just spews so much love for these people in your life, these people that have influenced your life, and brought you joy and strength. It's kind of a full circle in that way, and I just think that's beautiful. Because you do come back to that general premise of what about love, and just gives a lot of hope.

RJ: Thank you. Yes, that was really important to me while writing this, because I thought I'm writing about extreme brutality, and here I am sitting here writing it and it's hurting me, like I could feel the pain on my skin. What would this do to the reader? And how could I offer the reader or the listener a balm? I have to balance this with a profound loving care, with some joy, I have to find the joy somewhere. And that's what I tried to do with Samuel and Isaiah, was imbue them and the people who love them with as much love and joy as I possibly could to take us back to pre-colonial Africa, to see the kind of love that Samuel and Isaiah share be celebrated without any shame, to sort of give the reader and the listener something to hold on to, something to put a sort of healing balm on the wounds that are created in the other sections of the book. So yes, the most important thing to me in that book is love.

TF: I agree. That's what makes for me great literature is, like, as you said, just how important characters are. And especially in historical fiction that can sometimes be a little less in depth than in what's more traditionally thought of as literary fiction, but in the strain of Toni Morrison, her influence rings through in that beautiful combination of deep, real character, historical accuracy, and filling in the blanks of a history that we can't find outside of fictional exploration is pretty amazing.

RJ: Thank you.

TF: I want to thank Robert Jones Jr. for being with me today, and talking about his debut novel, The Prophets, which is available now on audible.com.

RJ: Thank you so much, Tricia, for having me. This has been an absolute joy.