Note: Text has been lightly edited for clarity and does not match audio exactly.

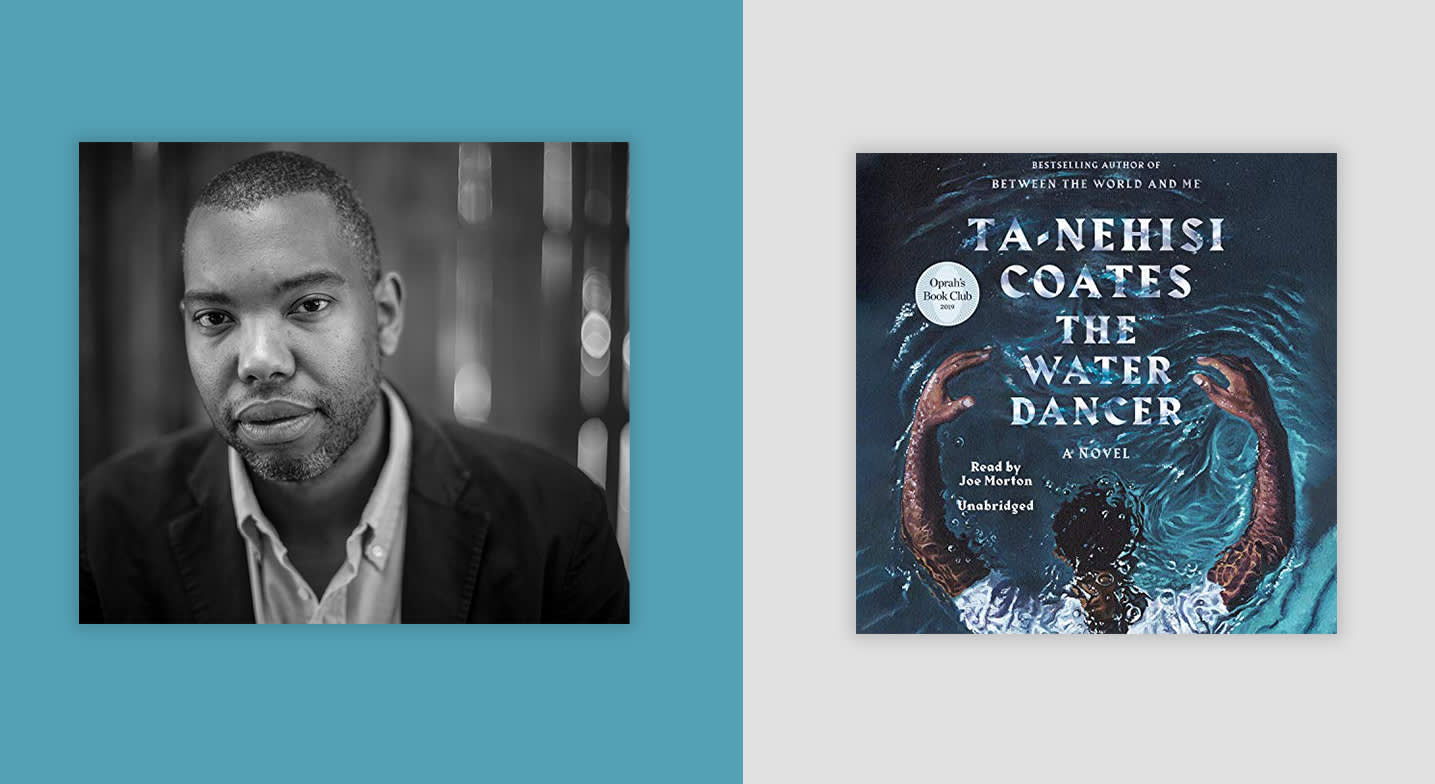

Tricia Ford: Hello, listeners. I'm Tricia Ford, an editor here at Audible. Today I am thrilled to be speaking with author and journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates. His books include The Beautiful Struggle, We Were Eight Years in Power, Between the World and Me, and The Water Dancer. He's a winner of the 2015 National Book Award for Nonfiction, is currently a contributing editor at Vanity Fair, and is the Sterling Brown Endowed Chair in the English Department at Howard University. Today we'll be talking about his new book, The Message. Welcome, Ta-Nehisi. Thank you for being here.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: Thanks for having me.

TF: Now, The Message consists of three intertwining essays, all read aloud by you, the author. You're the performer here. And each is born from separate trips you took to Dakar, Senegal; Columbia, South Carolina; and Palestine. In it, you're talking to your students, who you call your comrades, and it started as a writing lesson, I believe. The art of writing is very much a part of the story. But how did it transform into this kind of travelogue, on top of being something about the art of writing for students?

TC: Well, one of the core notions of The Message is that the writing is done best when it's not abstract, but when it's tangible and when it's felt, and not when it's theoretical. It became a travelogue because in order to demonstrate what I was saying, I had to follow my own instruction. And so the things that I wanted to write about, I had to see. That is a methodology that I've had for as long as I've been a writer, whether it's fiction or nonfiction. I'm not very good about just sort of sitting in my house and imagining the whole thing. That's not really my process. I have to see things, I have to feel things, because what I'm trying to do is convey a feeling to you, to the reader. And so I can't really do that if I don't have it in the first place.

TF: I'm sure that you went to each of these places with some preconceived idea of what you would find there. How surprised were you by what you actually found?

TC: I'm always surprised. That's the whole point of going there. If you know, you can't really go. I think for each place, obviously, it was a different sort of surprise. I had questions I wanted to answer, thoughts I had, but it's not even that you gotta look for a surprise, it's the very nature of the thing. What you know 100 miles away, 500 miles away, 1,000 miles away, it cannot be what you see on the ground.

TF: Would you recommend all writers to travel? Do you think it's an important part of the process?

TC: Probably what I would say to young writers, everybody has their method. I just don't know how you write without seeing. But maybe that's just me. I don't know.

TF: Now, are there different rules for writing fiction? Or do you think the same applies, where you need that hands-on research?

TC: I do. I do. Maybe other people don't, but I do. I have to see things.

TF: I agree. I'm a big proponent of immersing yourself, whether it's a culture or just a place, it could be down the street, seeing that firsthand. You talk about having a hunger for clarity and confronting myths. How can you—and this might be a little bit too theoretical; maybe there's some concrete examples from the book that we could share here—but how can you debunk a myth but not lose the truth that that myth represents?

"Writing is done best when it's not abstract, but when it's tangible and when it's felt."

TC: I mean, it depends on the myth. Sometimes you want to lose the truth.

TF: Right. True.

TC: Because that's the whole point, you know? So, it really, really depends. I guess I would say that probably myths that have durable truths at their heart can't really be debunked, because what they're saying is actually true.

TF: Well, it seems that there are things where, I don't know, I guess the lesson that's being taught is true, is a good thing, but the actual facts didn't actually happen exactly as people have come to understand it.

TC: Yes, yes, yes. But then, it's myth. So, I mean, that sort of goes into it. As long as it's saying that it's myth, as long as it's clear that it's myth, and it's not posing as history or memoir or biography, then I think it's okay.

TF: Now, one part of the book, and it's in several different parts, where it comes up where you talk about your childhood and your relationship with writing and storytelling. That has to be incredibly helpful for all the young writers that you're speaking to. But you talk about the goal of writing is to haunt readers, or in our case, listeners, and how in your childhood it became an obsession with stories and how this actually saved your life. I'd love to hear you talk a little bit about that. I thought that was a beautiful part of the book.

TC: Yeah, I grew up in a house full of books. I learned to read and write very early. And this was a time when there was no Google, there were no smartphones. There weren't even CD-ROMs at that point, earlier. Information was not easily accessible. And so acquiring information was extremely valuable. That's what the books were for me. They were a place to disappear into when I was unhappy. Quite beautiful and very, very important. And, eventually, I got to the point where I felt like I wanted to do it myself.

TF: Right. That transition, you talk about how did you go from being haunted to becoming the ghost, as you put it?

TC: Becoming the ghost. Still working on that [laughs]. I don't know. It's like I said in the book, I imagine for filmmakers and for painters, somebody is sitting there or laying on their bed and they feel, "Man, I would like to do this." I don't just experience this as pleasure, I experience the fact of being able to give that pleasure as remarkable in and of itself. And I probably felt like that. I felt like, "Man, I would like to do that. I would like to be the person who gives that sort of pleasure." And I decided to try. But I think people feel like that about all art forms, right? I think musicians, maybe they listen and they think, "Wow, I would like to do that." Or painters looking at something, "Wow, I'd like to do that.”

TF: How do you teach that to young writers?

TC: That part you cannot teach. I don't think you can teach that part. That’s just a desire, that's a what-you-want-to-do thing.

TF: Now, as a professor, since we're talking about that, I know that you're comfortable with speaking in front of people, and I'm sure you've done your fair share of book readings. But how did you like recording your essays in the booth? What was your experience in the recording booth like? Did you enjoy it? Did it open up anything different about your own book to you?

TC: Actually, I found it extremely difficult [laughs]. It was really hard. I mean, we were crashing, because we spent so much time up to the deadline writing. And so I found it hard this time, especially as compared to Between the World and Me. If you're not a trained reader of books, I mean, it's a craft, it's a skill, and everybody doesn't have it. I found it difficult, but I also think when people come up to me talking about that they're listening to it, they're very, very happy that I recorded it. So, I have to remember that.

TF: Yeah, you have a wonderful voice and I can't imagine anyone else reading those words. Along the same lines, did you learn anything new about yourself through the whole process of writing The Message?

TC: Yeah, I did. I mean, that's kind of what the book is about. I think in terms of what is not in the book, I learned that I have this really deep interest in global struggle, which is kind of where the book leaves off. And I look forward to pursuing that in future books.

TF: Now, just thinking of future books, I know The Water Dancer was a work of fiction. Do you think it's a strictly journalistic endeavor that you see, or do you see a potential novel?

TC: No, I probably would go back to novels again. I mean, you need a break. Nonfiction is very, very intense, and the reaction that I elicited is pretty intense. I probably would go back at some point.

TF: Well, I hope so. I like both. I love The Water Dancer, it's beautiful. The Water Dancer has a voice that will stick with me forever in Joe Morton. Now, are you a listener? Do you listen to audiobooks, podcasts?

TC: I do. I do very much. They allow me to read more books. I don't listen to them instead of reading books. But if I get a good reader, I'm in. There's some books where I have the audiobook, the e-book, and I have the hardcover of the book itself. They're different experiences, each of them. Sometimes with note-taking or whatever, I'll have one on. Just because I like to own books, I'll have the hardcover. But yes, I do listen to audiobooks.

"The message of The Message is that writing changes the world, but it's also that we need you."

TF: Do you have any favorites?

TC: Yes. Among my favorites is Tony Judt's Postwar. Ralph Ketcham reads that. It's a history of Europe after 1945. And there's another one that I am thinking of that is really, really good. And that is my buddy Eyal Press's book Dirty Work. The reader for that is really good too. One of the books I leaned on for this was Noura Erakat's book Justice for Some. I can't remember who read that, but I listened to that one also.

TF: That's Christine Rendel.

TC: Oh, she was very good.

TF: So, Ta-Nehisi, you talked about how you're speaking to your students here, or more broadly to all young writers around the world. And the call to action, so to speak, is that writing changes the world. If you had to put your message into one short phrase, what would that be?

TC: The message of The Message is that writing changes the world, but it's also that we need you. We need you. We need more writers that understand that lesson and take it as their job to use writing for that purpose.

TF: Thanks so much for taking the time to talk to me today, Ta-Nehisi.

TC: Thanks so much for having me.

TF: Listeners, you can find The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates on Audible Now.