Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

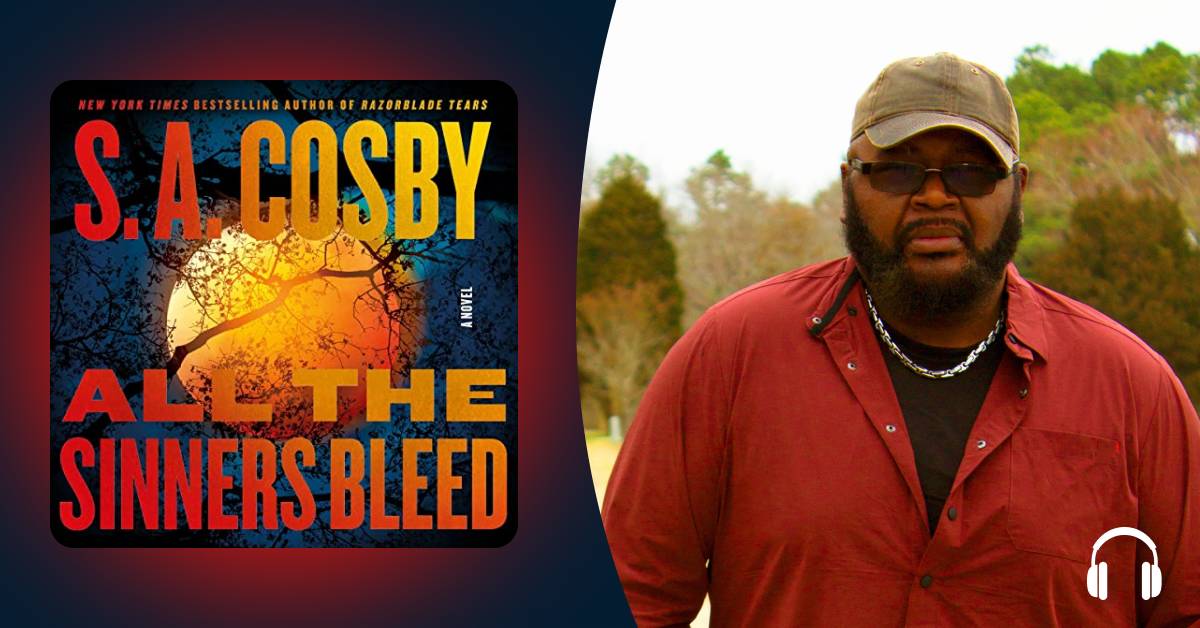

Yvonne Durant: Hi. This is Audible Editor Yvonne Durant. Today, I am starstruck because I'm interviewing the very wonderful writer S. A. Cosby, whom I had the pleasure of meeting in person at this year's ThrillerFest. We're going to talk about his most recent release, All the Sinners Bleed, and about his writing life. Shawn, can I call you Shawn?

S.A. Cosby: Please call me Shawn. That's fine.

YD: Okay. First question, well, kind of a statement and a question: I've been hearing a lot about Southern writers. Does anyone in your experience talk about Northern writers?

SC: You know, that's interesting because in my experience, Northern writers are sort of the default. It's sort of the idea that the Northern writer is the quintessential American novelist. And so Southern writing is relegated to this regionalism, but you have really great writers who I would postulate are really great American novelists as well, like Ernest J. Gaines and Alice Walker and William Faulkner and Flannery O'Connor and so on, and on, and on. So yeah, I don't really hear the phrase “Northern writers” used a lot. But I'm a proud Southerner, and I'm proud to be a part of that tradition.

YD: Titus Crown in All the Sinners Bleed, he has a lot of heart and love for this father and brother. Is he based on you? And I ask this because I heard in another interview you speak about your father and the time he didn't show up to take you out or visit you. And it wasn't because he didn't want to, but unbeknownst to you, he had had a disagreement with your mother. So I was wondering if this relationship you have in your books, does it relate to your life?

SC: It does and it doesn't. The relationship between Titus and Albert, his father, and Marquis, his brother, is sort of an idealized version of the relationship I had with my father. I've been able to repair the relationship, and I'm very, very thankful about that. My father's still alive and we've been able to sort of work through whatever issues we may have had. And so the relationship with Titus and his dad is sort of this, like I said, hyper-idealized relationship that I wish my dad and I had all along. But I'm also very, very lucky that we have a better relationship now. So I guess the answer is a little yes and a little no.

YD: Okay, I'll take that. Let's talk about church, the almighty church. Church is a powerful institution in Black lives nationwide and I, personally, like that you expose the drama and hypocrisy. Have you ever received criticism from your readers or people you know who know your work? Do you belong to a church?

SC: I do belong to a church. The church that I'm affiliated with was founded by my great-great-great-grandfather and seven other African American men shortly after the Civil War. That being said, I've always had sort of a complicated relationship with religion. I think religion can be an incredibly meditative and wonderful thing, but it can also be used as a weapon, as a way to manipulate people. My mother was very religious. She sent us to church every Sunday when we were kids. I think, as she got older, she was a little disillusioned with the idea of Church, capital C, which is the entity, the idea of a religious relationship, and church, little C, which is the building and the people in it, and how sometimes they can be hypocritical and they can be manipulative and they can be petty and small.

"My mother used to say to me, 'Birds got to fly and bees got to sting. And you got to write, that's what you were put on earth to do,' and I really believe that."

And so, it's always been something that I have been interested in talking about, but I never really tackled it head on like I did in All the Sinners Bleed before. I haven't really received any criticism yet, but you know, the night is still young.

YD: What about in your town, friends and family? Do they know your books? Do they ever say, "Hey, Shawn, was that me, that character so and so?" Or do they see themselves? Are they happy? Do they even follow your work? Just because you live there doesn't mean everyone's reading you. I would think they would. So do you get any of that?

SC: Yeah, the funny thing is everybody wants to be in the books. Like, everybody wants to be a victim or a murder victim, or a bad guy. Nobody wants to be a good guy, but all my friends and family are like, "Yeah, that's ..." They all assume characters are based off of them. But, to the larger point, I have an incredible amount of community support. I'm from a very small town and I know a lot of folks here, I'm friends with a lot of folks here. Even folks I'm not friends with, they seem to sort of see me as a local son done good. And so there's an incredible amount of pride and support here. I like to say even people that don't like me now support me. And I think that's sort of fascinating in itself, but I feel such an incredible sense of community here with the folks who do support me and really are behind me, and who love my work, and care about me, and are so proud of me. It's not unusual for me to be in the grocery store and someone just randomly walks by and is like, "Keep on writing. Keep up the good work. We're proud of you." I'm like, "I don't know who that is, but um ..." [laughs]. But I take that, I'm grateful for that. As an artist, you need all the support you can get.

YD: And I would think some of these people that you live close to and they're near and dear to you, they sometimes, or maybe often times, inform the development of your characters?

SC: Oh, yeah. Absolutely. My first book, Blacktop Wasteland, the character Bug is based a lot on—I have a cousin who passed away that was a mechanic. He was a gear head. So it's a lot of that. Part of that character was based on him. Ike is based on a relative of mine who, unfortunately, was incarcerated but changed their life around and really took to heart this idea of being a better person.

Titus, I think, is probably the first character who's not based on anyone I know personally. Titus is more based on an idea of a character that I had, of the type of character I wanted to create. I mean, I guess there are aspects of him that come from family members and friends and folks that I run into. But he's probably the first character who is sort of independent of my previous connection to people. I just really wanted to write this very strong, morally complex character. And so he's kind of the first one to fall into that category.

YD: That's interesting. My Darkest Prayer was rejected 63 times. How did you feel? Did you ever get angry because you knew you had delivered the goods?

SC: So, you know, I got angry at first. The first time, I was very angry. I felt like, “I'm writing well, I know I can tell a story.” I would read books in stores that were not as well-written as what I had written. And so, at first, I was angry, and then I got depressed. And then finally, I got angry again, but in a different way. I used that anger to motivate myself that I wasn't going to be denied. I felt like my work deserved an audience and I wasn't going to stop until I got there.

That being said, again, 63 rejections is 63 rejections, and it does sting. But I think deep down inside, ever since I was seven years old, I've always wanted to tell stories and I just felt like this is my purpose. My mother used to say to me, "Birds got to fly and bees got to sting. And you got to write, that's what you were put on earth to do," and I really believe that. And so I just felt like it was almost an inevitability. I never thought that I would have the success and the fans and the adulation I have now, and I'm so grateful for that. But I always thought, one day, I'm going to get published. And I think that's sort of the mindset you have to have as a writer and a creative.

YD: Okay, so I think maybe you've answered my next question, but just in case, any advice to writers on the subject of rejections?

SC: I think what I would say also about rejections is take the good from it and learn from it. Take the bad and toss it aside. Sometimes you get rejected where it's a really valuable critique on your style, on your ability. It is really a rejection that someone really wants you to get better. They see talent in you and you're not there yet. Sometimes you get a rejection where it's just somebody having a bad day and they decide to take it out on you. And so, you have to sort of learn to separate the wheat from the chaff, so to speak, in what you're getting. I got rejections in that 63-rejection period that were really helpful to me as a writer going forward. And I got ones that were just mean and bitter. So I think as a writer, as a creative person, as a sensitive person who's putting something out in the world, you have to learn to take, like I said, the good—“Okay, that's something pertinent to my style or my career”—and then the other stuff, just toss it away. So, it's difficult to learn to do that. It's hard, but I think if you can master that, you can take rejections and use them as fuel to fire your imagination.

"I wrote the book, but just the power and the dignity, and sort of this drama that [Adam Lazarre-White] brings to the recordings, it moved me."

YD: Thank you. That's good advice. Good insight. Do you remember how you felt when you wrote the last word in My Darkest Prayer? Did you sigh with relief? Smile? Maybe even cry? Did you have a toast with your wife?

SC: Yeah. So, My Darkest Prayer was my first book and I had, for a long time, thought I couldn't write a novel. I was a pretty good short-story writer then. My short stories were being published pretty regularly in different outlets, but I wanted to do something bigger, I wanted to do something broader. And when I finally wrote the last line, I remember leaning back from the computer and I looked at it, and I said to myself, "Yeah, that's pretty good. That's a pretty good closing line." And I just felt this immense sense of relief that I did it. I didn't know what else was going to happen with it, I didn't know what was going to become of it, but I had accomplished it. I had done something. And it's just this sense of accomplishment. It really never left me.

I used to be very self-deprecating as a writer. I would be doing interviews or podcasts, and I would say, "Oh, you know, if I can do this, anybody can do it. I'm nothing special." And a friend of mine, a gentleman by the name of Jordan Harper, he told me, "You know, stop saying that, man. If everybody could do what we do, they would do it, and they don't. What we do is special. What we do is important." And that's always stuck with me, since he told me that.

YD: Yeah, that's right. If they could do it, they would do it. I want to talk about your narrator, Adam Lazarre-White. I have to say, he nails the narration every time. I've heard him twice. And I love the way he does the narration of female voices, that pitch he has, it makes me smile all the time. How did you know he was ideal for your work?

SC: That's an interesting story. When I did my first book with Flatiron, which was Blacktop Wasteland, they sent me four or five audition tapes for narrators for the Audible aspect, and the first three narrators were awful. I can't say that another way, because they were trying to affect a Southern voice, a Southern drawl, but they were doing it to the point where it was cartoonish. And when I heard Adam Lazarre-White's voice for Bug, the main character, he sounded just like Bug sounds in my head. And I said, "This is the guy. This is the dude." And then when he did Razorblade Tears, I remember telling him, I said, "I want you to narrate all my books," because there's something he gets about my work and what I'm trying to say, and how to articulate my characters that nobody else does. And I heard some of the early stuff for All the Sinners Bleed, and, man, the voice he gives Titus, it's, again, it's the voice of Titus that I heard in my head when I was writing.

He is such a talented person, such an incredible narrator, such an incredible actor. And I wish my grandmother was still alive because when I was a little kid, she used to watch him on Young and the Restless when he played Nathan Hastings. If you're a Southerner of a certain age, you were raised by your grandmother, Young and the Restless, and Victor Newman. And it just tickles me all the time that the gentleman who played Nathan Hastings is narrating my books. I know my grandmother must be smiling up in heaven, but I'm very lucky to have him narrating my work. I'm very lucky that he connects with it on such a deep, visceral level.

YD: You gave him a little nod in Sinners. There's a character named after him, right? Lazarre?

SC: Yeah. Just a little nod to him.

YD: It was kind of neat. It made me smile. And, oh, let me ask you, have you ever listened in its entirety of any of your books on Audible, the audio?

SC: I know this is going to sound self-indulgent, but yeah, I do it all the time [laughs]. I love it. I had a long car ride about a month ago. I went to a college out in the western part of North Carolina, so it was about a four-hour, four-and-a-half-hour drive, and I listened to Razorblade Tears. And I wrote the book, but just the power and the dignity, and sort of this drama that he brings to the recordings, it moved me. And I mean, I know what's going to happen, I wrote it, but there's something about hearing him perform the voices of Ike and Buddy Lee that I think is remarkable.

"When I write a book, I want a book that in 10 years or 15 years or 20, in however many years, somebody can come and read it and realize that's a snapshot of the world and the country and the place we were living in. That's a responsibility that I both enjoy and take close to heart."

YD: It's pretty cool. So, I think I mentioned the other night, but maybe I was two Proseccos in, maybe you had a beer. I don't know what you remember, but I recited some of my favorite lines, like the one about the guy who had so many spaces in his mouth he should've put a sign up, “Next tooth a mile ahead.” In All the Sinners Bleed, Titus observes Officer Pip's paunch. That's nice alliteration. "The bottom three buttons on his shirt were performing a labor of Hercules as they kept his belly from spilling out." Hilarious. And then, oh, and I have one more from a colleague. She loved this one in Razorblade Tears: "His large and small intestines began to unspool like a ribbon of saltwater taffy soaked in Merlot." Where do you come up with these lines?

SC: Thank you so much. So, I grew up around a lot of backyard orators and cookout raconteurs. I was blessed to be in a family with uncles and aunts who were very humorous and very gregarious and loquacious. I grew up in a family that, if you didn't like being picked on, don't come to one of our cookouts, because that was sort of our entertainment. We picked on each other and we made fun of each other, but in a loving, good-spirited way. And that sort of stuck with me. It became a part of my writing style. It makes me happy to write those lines because I feel like I'm channeling my Uncle Buck and my Uncle Cecil and my Aunt Margarite. And when I write a line like that, it feels like they're talking through me at one of our family gatherings or get-togethers. And I think it's something I use to sort of color my own specific style, but I try to use it judiciously. I have a good editor at Flatiron, named Christine Kopprasch, who helps me use it in the right moments. We have a joke that I'm limited to two metaphors or one simile per page now.

YD: That's funny. That line reminds me of a line I heard a long time ago: "He was so ugly he hurt my feelings." Don't you love that?

SC: [Laughs]. That's pretty ugly.

YD: So, The Rhythm of Time, your collaboration with Questlove, did you find it very challenging writing for children?

SC: You know, I did at first when they approached me about it. Obviously, I was excited. Doing work with Questlove, one of the great drummers, great musicians, great articulators of hip-hop culture. But I remember asking them, I was like, "You sure you want me to write a children's book with Questlove? Have y'all read my other books? Because, you know, people tend to get shot in the face and stuff." And he said that he just loved the way I wrote. He loved that sort of poetic style that I brought to my writing.

And so, I will be honest, as a crime writer, as a writer of suspense and crime fiction, sometimes you lean on violence, sometimes you lean on, as my mother would say, colorful language. You can't do that with a kid's book, and so it really helped me. What was at first a challenge became sort of this learning experience where I was able to really distill my storytelling style down to a really interesting finer point. And it proved to me that I don't need to lean on certain tropes or things of that nature, that I can still tell a really interesting, fun story for a different audience, for a whole different type of person that's maybe not somebody who's a fan of my other work. Working with him gave me such versatility, and I'm so grateful for that experience.

YD: What's the one thing you want your readers to know about your writing?

SC: That it’s really hard [laughs]. No, I want people to know, it is hard, but it's also the great joy of my life, other than my family. No, I think what I want people to know is that, while I may not take myself very seriously and I can be self-deprecating, I take the art of writing very seriously. I'm going to give you an opinion that I think some people don't like, but I really think is true: You can learn the technical aspects of writing. You can learn how to form a sentence, how to verb-subject-agreement, how not to use passive voice, but you can't be taught how to be a storyteller. I think you either are or you aren't. Or as my mother would say, you either is or you ain't. And I think there are certain people who are just born storytellers. You can get better. You can improve. But I think there's an innate spark that lives in you. And so I take that very seriously. I take the responsibility of writing very seriously.

I can't remember who said it, but I remember a quote, "Civilizations are only as good as the stories they tell about themselves." And I think writers are sort of the arbitrators of that. We are the modern myth makers, and I take that very seriously. When I write a book, I want a book that in 10 years or 15 years or 20, in however many years, somebody can come and read it and realize that's a snapshot of the world and the country and the place we were living in. That's a responsibility that I both enjoy and take close to heart.

YD: One last question. Your wife, does she still own a funeral home?

SC: Yup, she sure does.

YD: Are you a regular visitor?

SC: I used to work there. I used to help her run it and do things. My career is such now that I don't help out as much. However, if called upon, I will still jump in the hearse and we'll go for a ride. I don't have any problem doing that.

YD: Okay. Well, this has been wonderful and I'm honored. You know, this means a lot to me. And listeners, thank you for listening, and I strongly advise you to listen to All the Sinners Bleed. It's on Audible, waiting for you. It is an excellent listen. Thank you so much.

SC: Thank you for having me. This was a pleasure.