Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

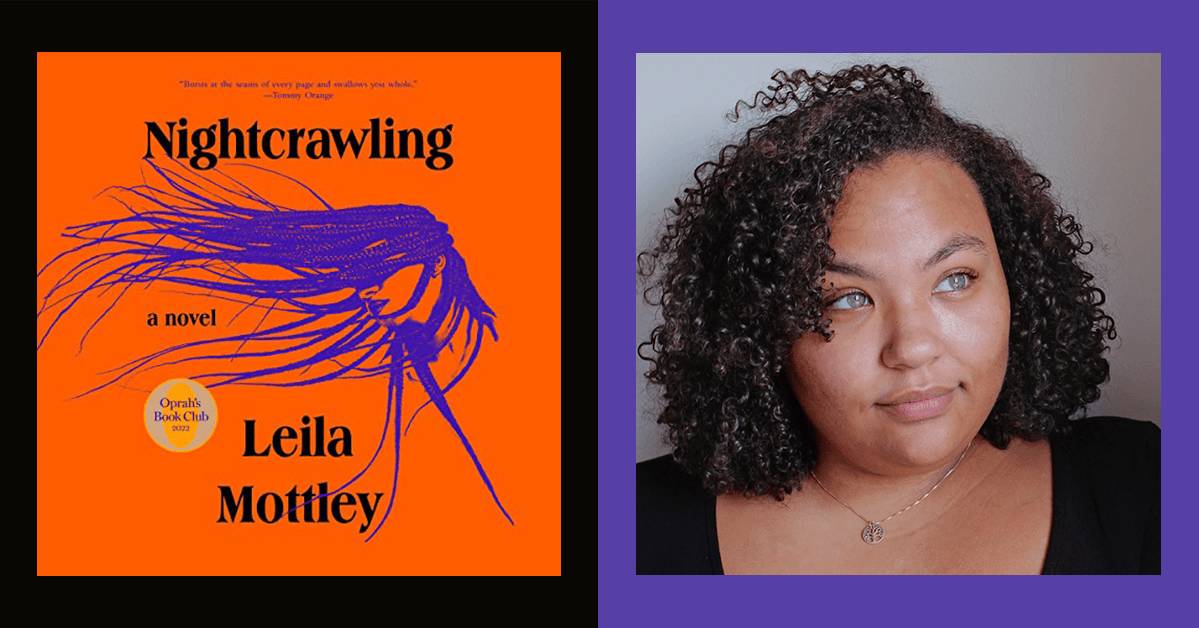

Kat Johnson: Hi, listeners. I'm Audible Editor Kat Johnson and today I'm privileged to be speaking with Leila Mottley, whose debut novel, Nightcrawling, is a gorgeous and absolutely gutting story of how one teenager's efforts to survive lead her directly into the path of dangerous predators, the most dangerous of which is the justice system itself. Despite the dark subject matter, it's also a stunning story of resilience, hope, and beautiful prose, and it heralds the arrival of a major talent. I'm so thrilled you're here with us today, Leila. Welcome.

Leila Mottley: Thank you for having me.

KJ: Thank you so much for being here, and congratulations on this novel. It is the best thing I have read or listened to all year, and I've spent time with it both ways. It absolutely sings in both mediums, which is a credit to your prose, which is so lyrical, and the character of Kiara who guides us through this story. Am I right in saying you began writing this novel when you were only 17, like Kiara?

LM: Yeah, I wrote most of it when I was 17. I think I wrote the first chapter when I was still 16.

KJ: Wow. And you have a background as a poet. You were the Youth Poet Laureate of Oakland, California, when you were just 16 years old. Is that right?

LM: Yeah, I've been writing poetry since I learned how to write, but I've also been writing fiction. I was a performance poet. I did a lot of spoken word, slam poetry, and I was the 2018 Oakland Youth Poet Laureate too.

KJ: It's incredible that this is your first novel and that you were so young when you wrote it. For listeners who might not know, can you say a little in your own words about what the novel is about?

LM: The novel follows Kiara, a 17-year-old Black girl living in Oakland, California, when she finds herself involved with a network of police officers who sexually abuse her. It's about the major investigation that comes out of that, and about vulnerability, and Black girlhood, and our lessons and what we owe to each other.

KJ: This was based on a real case. This horrifying story of sexual abuse of a teenager by a network of police officers in Oakland was based on real events that came to light in 2016. How did you come across that story? And how much of the real events informed Nightcrawling?

LM: This case was a huge deal in the Bay Area. I grew up in Oakland and still live here, and when this case broke, it kind of consumed our local media for a while. And I remember paying a lot of attention to this. I was 13, 14 at the time, and I remember just focusing on all kinds of things about this case and feeling really fascinated by it and by what it represented. Because there seemed to be this skew about the way that the media talked about the case, where there was this disproportionate attention on the police officers and what the repercussions for them were going to be, and there was very little about the harm done to this young girl and to the thousands of other young girls and women who experience this kind of thing regularly.

KJ: It's amazing that you were able to pick up on all that when you were 13, 14. I think it really takes someone of your age to get into Kiara's head. I'm curious, you obviously have some things in common with Kiara. You're from Oakland, you're similar ages. How does Kiara intersect with the real-life story versus what you just sort of imagined and invented for her?

LM: Kiara's entirely fictional, and I always say that this case was kind of the seed for the idea. I also went into researching other cases of police sexual violence and really wanted to tell a story of a young girl and her world, and I wanted it to be complete and whole, and that meant creating this fictional person and all of the things that make her up and make up her world. She really is fictional, but I think that I always pull from all kinds of different things, every person I've ever met and my own experiences. And so sometimes I am pulling and sometimes it is just coming out of my imagination, and it's always kind of a blurry line.

"I always pull from all kinds of different things, every person I've ever met and my own experiences."

KJ: When the story starts, Kiara's 17, living in these apartments called the Regal-Hi, but they're not quite so regal. She's with her brother, Marcus, who's a little bit older, and an aspiring rapper. They're in need of rent, and she's a high school dropout, so she's kind of trying to help him make his dreams come true. He wants to shoot his shot, so when their landlord hikes up their rent, she falls into this situation where she gets paid for sex. The way that you set this up with her being so vulnerable and not even knowing what's happening is really incredibly powerful. And I feel like the way that you weave this all into the character is one of the great pleasures of the novel.

LM: Thank you.

KJ: I'm just curious how intentional you were about that and what the writing process was like for you, because it's such heavy material.

LM: I was really intentional about all of it, and I think that's part of what happens when you revise so deeply, as every choice gets made, with all of the intention in the world. I knew that I was telling a story that was going to be intense and uncomfortable at times, but I also immerse myself so fully when I'm writing, and it's partly because I write in first person and so I have to enter this character's mind. And so when I was writing Nightcrawling, I didn't even think of it as the kind of dark tale that it can be.

And I've heard recently from readers how intense it can be, as a reader, but for me as the writer, I just try to tell the most authentic story. I think that Kiara experiences a lot outside of this idea of what is dark or tragic, and so I don't think she experiences herself that way. So, I wanted to really show the intricacies of her mind and all of the different ways in which she thinks and doesn't think and how other people's expectations of her and ideas of who she is are often not in alignment with her ideas, and how that creates these situations.

KJ: And I think you being the same age, you're able to come at it from that really authentic perspective, where when I was Kiara's age, I certainly got into not-quite-as-dire but similar situations — where she's on that rooftop, just how vulnerable she is. So many women don't even realize at the time that it's happening, so I think the way that you did that was so effective, and quite chilling.

I was thinking, too, about the last time that I felt so blown away by a debut novel, and the one that came to mind for me was There There by Tommy Orange, which is funny because then I learned he's a huge fan of your work, and his novel, of course, is set in Oakland as well. So, I wanted to talk to you about Oakland. It's such a strong presence in the story. What did you want to capture about the city?

LM: First of all, I loved There There, too, and it was really the first representation of Oakland that I felt like, “Wow, that is a representation of my city.” And yet Oakland has all of these different sides. And I wanted to kind of show a glimpse of my part of Oakland. I thought a lot about what I wanted to do in my depiction of the city, because I think that often in media depictions of Oakland, there tends to be this binary—either it's a city that is told to be crime-ridden and dangerous or a city that is on the come up. And I think that both of those neglect to recognize the rich history of Oakland and all of the different sides of what it is and how vibrant and rich and beautiful it is. I wanted to show all of that and to give Oakland the respect that it deserves and encapsulate it, if I could, into this book.

KJ: I think you absolutely did. And, of course, as a poet, I think your word choices are so intentional. And I'm sure you must've thought about the audio performance of this story as well. Do you read your work aloud to yourself?

LM: Mm-hmm.

KJ: Do you have strong opinions about how it sounds?

LM: Yeah, I read it aloud to myself, and so it's always in my voice when I'm reading it. I knew that it was going to be an adjustment hearing someone else read it. I really wanted to make sure that the narrator could capture the cadence and the rhythm of the book and that that wasn't lost in the narration. That was really important to me when we were choosing.

KJ: The narrator is amazing.

KJ: Her name is Joniece Abbott-Pratt, and she's incredibly talented and has a lot of experience. I think she's the perfect voice for Kiara. Were you able to give any direction at all to Joniece? Or did you have any involvement in casting?

LM: I had a little involvement in the casting process. We heard the tapes of a few different people, and I heard Joniece read it, and it just sounded right. It was as close to Kiara's voice as I was going to get without having a real Kiara [laughs]. It was the perfect fit from there.

KJ: I think it's an amazing choice. And I'm actually going to play a little clip for listeners so they can hear the performance and hear your gorgeous prose. I saved so many notes and clips and pieces of this book. This scene is toward the end, when Kiara is leaving the police station and she comes across protesters.

Joniece Abbott-Pratt: On the short walk from the exit to the waiting police car, I hear the sound of megaphones, drums, and chants. A few blocks down the road, hundreds if not thousands of people march toward the building, their voices a thick chorus, a call and response with Freddie Gray's name sharp in the center. And I watch Harrison's head lower as we reach the car. I climb in the back and look out the window. I wonder if they'll ever chant about the women too, and not just the ones murdered but the particular brutality of a gun barrel to a head, the women with no edges laid, with matted hair and drooping eyes and no one filming to say it happened, only a mouth with some scars.

KJ: I mean, I could keep going. I guess I just wanted to ask you, you're an activist yourself, how do you see your writing work as part of your activism?

LM: Well, I definitely don't claim activism as a title or anything. I just know so many organizers and people who do this day in and day out, and I have just all the respect and I'm in awe of them. But I do think that part of what makes art so important is the way that it can expand our ideas of the world that we live in and where we are and who we are. And I think that having this story is part of the work to make sure that we are visible. And there's a lot to do after that point, but I think that's the beginning of confrontation and acknowledgement.

KJ: I appreciate you don't claim the label activist, but I do know you're the founder of Lift Every Voice, which is a youth-led art advocacy workshop about youth incarceration, so I know you have roots in that area. I tend to listen to a lot of true crime stories, and it's really frustrating because there's just so much injustice everywhere and there's crime everywhere, and it's really hard to know which cases to pay attention to. But what would you say, for folks like me or people who feel like it is so hard to do everything and to focus on the right things, how do you think people can help? For those of us who are really moved by Kiara's story, would you suggest any next steps?

LM: Well, politics are about people, so whether you read this story as a story of characters and a fictional world or you read it as something to learn from, either way, what we need to do is invest in each other in the same way that we can invest in a character's fictional world. Because the spectrum of feelings, the whole interior world, all of that happens for every single person. And if we stop thinking of a headline as a headline and start thinking about it as a person and thinking about what it means for us to be complicit in all of these systems and how we as individuals can change the ways that we expect Black women and Black girls in our lives to behave or what we expect to be done for us. A lot of what I wanted this book to do is show the expectations and the obligations that are put onto Black girls before we even have an understanding of what our options are. Because that is an expectation almost from birth, there isn't a questioning of it. I think that what we all can do is question the small moments where we expect something from Black women without asking first.

"A lot of what I wanted this book to do is show the expectations and the obligations that are put onto Black girls before we even have an understanding of what our options are."

KJ: You do that so beautifully in the novel. When you were speaking, I thought about the scene where Kiara—I don't want to give spoilers, but her mother has been taken away and she's now alone with her brother. And her brother's this really interesting character: you love him, and then you also want to shake him. There's this scene where she's so young and he's going to take care of her, and then he orders pizza for them and he eats all the sausage slices and leaves her to clean it up. And she's like, "I should have known what was going to happen.”

LM: Yeah.

KJ: You're so young, and your generation is dealing with so many heavy issues that you did not create. What would you say to older people who maybe aren't listening or don't understand? Do you have a message that you would share?

LM: I think that, for a lot of us, when we move out of adolescence, we kind of immediately separate from it and, in retrospect, end up, I think, coloring adolescence as a time of not knowing and having these big emotions and irrationality and angst that we attribute as a culture to teenagers. And I think that it's really easy for us to do that the second we step outside of it. But I know that young people have such amazing ideas. The brilliance there often just goes unacknowledged. And I think that we have such low expectations for teenagers, and such a low threshold of what we're willing to tolerate or listen to. I think that all people who are now outside of that need to remember what it was like to be inside of it. Like, I was 17 when I wrote this and I was in it.

KJ: Yeah. And it's interesting what you say about expectations because I feel like that connects also to what you were saying about Black women being expected to shoulder so many burdens. We talk about Black girl magic and how amazing Black women are, but they are expected to do so much and be so much in the culture—and I think about that as a parent raising a boy and a girl, how we tend to expect less from our boys. It's just perpetuating this cycle of disparity and violence. So, I'm really glad that you brought that up.

What do you think gives you hope and joy? I'm so excited for people to discover this novel. What's coming next for you? What can you share with us?

LM: I am working on another novel. I can't say too much about it. It definitely has a tonal shift, but carries some of the same themes. It's set in a very different place with some very different characters, but I’ll hopefully be able to say more in a few months. And then I have a poetry collection coming out, too, in the next year or two, which I'm also excited for. I guess to answer your question about what gives me hope, I think that just recognizing that, as people, in order to move forward, we all have to cling onto some kind of faith, in a world that doesn't promise us anything different. I think that’s just such a beautiful thing that Black people have been doing for centuries, finding ways to hope and want and cling to different things and experience a wide spectrum of different moments and experiences and emotions despite all of the circumstances that make that feel impossible.

KJ: Thank you for that, that's beautiful. I know that there is going to be a wide audience for this novel, but I really hope that there are many women who feel seen and heard by this book. It's just so beautiful. It's just been such a pleasure.

LM: Thank you so much.

KJ: Thank you. And listeners, Nightcrawling by Leila Mottley, narrated by Joniece Abbott-Pratt, is available on Audible now.