Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

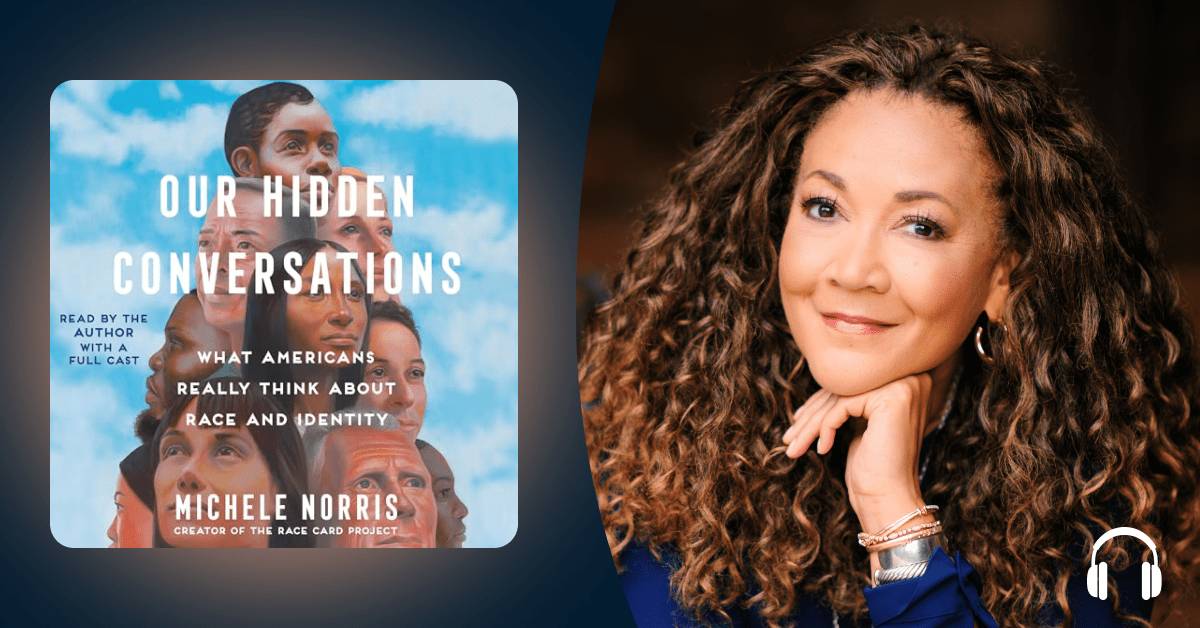

Yvonne Durant: Hello, listeners. This is Yvonne Durant, editor at Audible. And here today we're going to have an amazing conversation with Michele Norris about her incredible book, Our Hidden Conversations: What Americans Really Think About Race and Identity. There is no other work like this in the world, right, Michele?

Michele Norris: It is unique [laughs].

YD: Yeah, it really gives pulling back the curtain a newfound meaning on the subject, on any subject, whether the subject of race, a subject, as you pointed out in the book, people really don't want to talk about. Yet, 500,000 people wanted to talk about it.

Just let me give you a little bit of background on Michele Norris, a person I've learned a lot from when she was the cohost of the award-winning NPR program All Things Considered. It was a great show, and thank you for all that I learned from you and your team. It was just wonderful.

So, here we are to talk about race. And it began with a project. I came in on the project, by the way. I was surfing the internet in between writing hair commercials, because I'm a copywriter by trade. So I was surfing the internet and I came across The Race Card Project. Three things were posed: race, your thoughts, please send. In my case, I was so happy to be able to say what I said. And what I said is, "It is okay to see my color." We had to use six words, no more, no less. But with your cards, the post office got busy and that leads me to another copywriting story. I worked on a post office account for a small Black agency, and we learned that people weren't using the post office enough. They weren't writing letters anymore with the advent of all these tools that we have and our computers, our phones. And so I smiled when you said your parents worked [there]—and in fact, the post office needed business. So you really gave them a nice boost.

MN: [Laughs] Thank you. My mother was very happy about that. She is retired. My father's gone to glory, but my mother is still with us. And she was happy that I was supporting the US Postal Service.

YD: Well, you certainly did, big time. Besides the fact that 500,000 people responded, what was the next big surprise for you?

MN: Yvonne, there were surprises along the way, every step of the way, and I still am awed and astonished when I go into the inbox daily. I was surprised that people took the bait in the first place. I went and I printed 200 cards initially. And since you have a connection to the post office, you'll appreciate that the first cards we printed weren't the right size. My mother let me know that they weren't regulation size. So the first cards that were moving through the mail were not street-legal. We had to get that right, and we fixed it.

"What we're trying to do in this project is help America see itself when it comes to race and identity. And so we're holding a mirror up to America."

But I was surprised at the intention behind that, that people would find the postcard that I would leave at a book event or leave in a hotel or leave at an airport or a train station, at a restaurant in the menu kiosk. I'd just slip a card in there by the ketchup bottles and the mustard and the salt and pepper. And that they would take the card, write their story and then go and find a stamp, and then go and find a mailbox and send it in. I was surprised by the intention behind that.

I was surprised by, at first, the small number of people that were sending their cards back, and then the large number of people that were sending their cards back. I was surprised, and maybe I shouldn't have been, that it jumped so easily over into a social media space, because at that point what we used to call Twitter and Facebook and all of these social media platforms were really starting to percolate in a new way. And so people were actually posting their cards and discussing them in places like that. I was surprised that they came from cities I'd never been to, from cities and towns that I had never heard of.

One of the two big surprises for me was that we had so many cards that came from white Americans. I thought the majority of the cards would come from people of color. I'm a Black woman. I'm talking about race. I thought that's who'd pull up to the table. And in the 14 years that we've been doing this, the majority of those years, the majority of the cards have come from white Americans in the US. And we have cards from more than 100 countries. The book just focuses on the cards from the US. Maybe that's the next book. So that was the one big, big surprise.

And the other part of that big surprise, and that speaks to the title, it's called Our Hidden Conversations: What Americans Really Think About Race and Identity, that so many of them didn't have to think about race in the way that we normally think about it, in terms of hair texture and skin color, eye color. They had to do with geography. A lot of them having to do with class. Someone has red hair. Someone's in the military. Someone is an athlete. And that's the only thing that people see. Someone is an adoptive parent and suddenly they see all kinds of things differently. And so that's why I called it The Race Card Project, but when I talk about race, I almost always talk about race and identity or race and cultural identity, because that was really eye-opening to me that people want to talk about race but sometimes in a very personal way, which means they're talking about the many facets of their identity.

YD: You started the project, was it 14 years ago?

MN: Yeah, 2010.

YD: How many years in did you realize you had a book in the works?

MN: Pretty quickly. I thought, "Okay, this is probably going to be a book one day." But I was hosting a show where I had to consider all things by 4 o’clock [laughs]. And then I was busy being a reporter, so I didn't really have time to service a book. But I knew that I had to service the archive. So the little, teeny team that I work with, we really took care of these cards. We would tag them when a card came in, so if we wanted to find all the cards from Tennessee or all the cards that mentioned farming or all the cards that mentioned travel—we are not archivists, but we were trying to learn how to archive these cards correctly. And now most of the submissions come in online. They come in digitally because we created a website and then a portal for people to share their stories that way. And we continued with the tagging and with carefully putting them together.

I would say it was probably about four or five years in I got serious about this and started thinking, "Okay, I've got to think about the themes," starting to realize that I have an opportunity to interview people longitudinally, to actually follow their stories as they evolve. And then by about 2012, I knew this has to be a book. I had to figure out also how to just keep the project alive because it was something I was doing in my house, trying to figure out how to fund it, how to keep the database alive and growing. And then about four to five years ago, got really serious. And I'm fortunate I have a fantastic agent, and I partnered with Simon & Schuster. And then we just really got about the business to try to figure out how to get our arms around this massive archive, how to package it.

And the packaging of this was very important to me, both for the physical book and the design and for the audiobook and the audio design as well, to make sure that we were creating something that leapt off the page for people who were looking at the physical book and leapt into people's imaginations for people who were listening. I wanted to create an audio experience. And so that's sort of the evolution.

YD: Well, I must say, having listened to a good part of the book—and I have my book, my copy at home—when you hear these words, it is so powerful and so stunning, the experiences people have had, how they put those experiences, six words, which I'd like to know, why six words? Why not 10 words? It's a word a second. It could've been 10 seconds. Why did you choose six words?

MN: Well, I knew that, first of all, that limiting the number of words would be useful because it would force people to distill their thoughts to the essence of what is most important. That's something that I try to do as a writer when I'm taking on something simple or something complex, reduce it to one sentence, then I could tackle it. I thought six for a few reasons. I knew that that was something that people understood. There were lots of other six-word exercises out there, and so the concept would broadly be understood. There was that famous story about Ernest Hemingway writing a killer short story in six words, “Baby shoes for sale, never worn.”

But I also liked the sort of pentameter of six words. There was a certain cadence, a certain rhythm to six words that was different with five and different with seven. And so that's why we settled on six. We were also using postcards at the beginning, so brevity was also important because there just wasn't a lot of surface space.

YD: I like the way you framed this that these stories allow for eavesdropping with permission. We get to walk through Americans' neighborhoods. And this is not just another survey, if anyone's thinking that, you know, “What Americans are thinking.” But, like, the woman who her parents, a mother found her grandfather's Ku Klux Klan robes going through his stuff after he'd gone on to glory. And those you've mentioned are breadcrumbs, actually.

MN: Yeah. I mean, someone who realized that grandma and grandpa met at a Klan rally. Not something that the family may have wanted to talk about. Another one, someone discovered that the cemetery in back of the family plot of land was a slave cemetery. And I think it's a bed and breakfast, an inn of some sort, and they keep trying to rename it. And the family is kind of at odds, “Do we call it the slave cemetery or the cemetery for the enslaved? Or do we come up with a new name that maybe doesn't sound, you know, quite as difficult?”

I guess when you asked the question about what was surprising, that was slightly surprising too was—and maybe it shouldn't have been—that so many people reached to their forebears, their grandparents, in telling their stories about race. That they were talking about something they discovered or some gulf between where they are and where their grandparents were or are now. There's a whole chapter in the book called “Breadcrumbs” because in so many of these cases, the people who lived a certain life, whether it's the story of how they came to America or the story of who they were as Americans in the '20s, '30s, '40s, the stories of “Hush, they'll take Grandma away. If the town knew that Grandma was actually Indigenous, they might take her away and force her to live on the reservation.” So, these little pieces of stories that people of a different generation are trying to figure out how to tell younger people, but they don't know how to say it outright.

"It's the most important work I have done as a storyteller and a story collector, but it's not a panacea. It is not going to provide balm for a wound that has been with us for a long time. But it is somewhat diagnostic."

And I found that in a lot of these stories, they left little clues so that people could figure it out. The woman whose grandfather gave her an invitation. She was playing poker with him, nine card stud. If you play poker, that's a tough game, a lot of exposure. And she was young, and she beat him. They played several games and then in one game she actually bested him. And she does not know to this day exactly why he left. He got up, went into a room, came back out with an envelope and handed it to her. And she's like eight, nine years old. And he hands her this envelope and inside the envelope—he's a former law enforcement officer—inside the envelope is an invitation to something that he had to attend as a law enforcement officer. It's an invitation to a hanging.

YD: [Gasps] Oh my God.

MN: A triple hanging, that he gave to a young child. And she asked him all kinds of questions, "Oh my goodness, what happened? Three people?" And it's so wonderful to hear her tell her version of the story because her grandfather was a smoker. He was an older man, and she does an imitation of his voice. And he just says, "It was awful." But he didn't want to talk about it much beyond that. And she's in her 70s and is still trying to figure out why he gave her that. You know, did he say, "This is what America used to be. Maybe you can be different." She's not entirely sure, but it has shaped her, she said, in some ways and the way that she sees the world and what she's deciding to teach her own children and now her grandchildren.

YD: Yeah, that's intense. I want to play a clip. Some of them were blood boilers. I said, "Are you kidding me?" But you know what? Kudos to them for being brutally honest. Here's one:

Clip from Our Hidden Conversations: “White privilege, enjoy it, earned it.” —Douglas Thomas, Florida. “I'm not apologizing for something I had no control over. Every major contribution to mankind was done by people of my race. Society owes white people a debt of gratitude, not scorn.”

YD: So, kudos, as I said, to him for being brutally honest, and also stating his name. I think they tell their real names?

MN: In many cases, first name, last name. Sometimes just first name, sometimes the city where they lived. Some people chose to be anonymous and we honored that, so they're listed as anonymous.

I don't agree with what he said about the contributions. I think lots of different races have made contributions, but that is a viewpoint that we intuit is out there. But now we know, because you hear it! You see it. And what we're trying to do in this project is help America see itself when it comes to race and identity. And so we're holding a mirror up to America. And when you hold a mirror up to America on this issue, you're not going to like everything you see, no matter what perspective you embrace yourself. And some people have criticized our team for including stories like that, but we're trying to show America as it is. We should not pretend that that attitude does not exist. It absolutely does. And in some cases, when people send in stories like this, that's their anthem. They're proud of this. They live in a space where no one would wag a finger at them for that. They would probably say, "Right on. Thank you for speaking up for us."

YD: Right, well, that's happening across the country. I want to play something else, and this one means a lot in light of what's going on in the Middle East. I'll play this one:

Clip from Our Hidden Conversations: “I'm lucky I don't look Jewish.” —Alice Swenson, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. “Now that I'm incognito as a Jew, having the last name Swenson, when people do find out, they do say this from time to time. It bums me out every time. What does a Jew look like? Like me. This is such a backhanded compliment. I never know what to say. Thank you? How dare you?”

YD: I live in a neighborhood, Upper East Side, synagogues, Shabbat every Saturday. And a neighbor of mine said, "I don't think they should wear their yarmulkes right now with the war going on." I said, "They should put two and three yarmulkes on. They shouldn't hide who they are."

MN: You know, there's so much packed into that. And all the more complicated because of what's going on in the Middle East right now. You know, where she says, "You don't look like a Jew," what does a Jew look like? I mean all shapes, all sizes, all hair characters, all colors. I happen to know Sephardic Jews who are darker than you or me and are of African descent. There are people who convert to Judaism. Sammy Davis Jr. was a Jew.

YD: Exactly.

MN: And so we have this idea of what certain people should look like. And we're always trying to put people in boxes. But her response to that also, "How do I respond when someone says something like that?" And is the onus on her to respond? Do you just walk away? Is it a teachable moment? Is it a moment of retort? People really struggle with this.

It's interesting, I had a conversation with someone earlier today who had almost the same thing said to her. In this case, "You're pretty for a Jewish woman." That it was said out loud, and she struggled with what to say about that. We were both talking about how your brain almost freezes in that moment, and then later on you think of 17 things you should say, when you're in the shower or you're on an afternoon run or something like that. But you don't know what to say in the moment.

"I make my living behind microphones. I step on stages and speak to large groups of people. That was not available to my grandmother. She stepped on the stage that was available to her."

When people listen to a story like that, they may not be Jewish, but they may think, "Oh, someone has said something to me like that." You know, “I talked to you on the phone, you don't look like what I expected.” “You don't look like you're Puerto Rican.” “You don't look like you're of German descent.” “You don't look like you're Middle Eastern.” And it's kind of amazing to me that so many people write in about these things, because it means that so many people are hearing it, which means a lot of people are saying it. And the filters aren't engaging before they speak in that way.

YD: So, Michele, this book reaches across America, places in between and abroad. Do you think maybe the tide will change? Do you think it's going to affect the way we see race, live race, speak race?

MN: You know, I don't know. I do say this, that my work is important. It's the most important work I have done as a storyteller and a story collector, but it's not a panacea. It is not going to provide balm for a wound that has been with us for a long time. But it is somewhat diagnostic. And that goes back to including a story of someone who says, "You don't look like you're Jewish." Or a story of someone who says, "White privilege, earned it, enjoy it." Because then you understand the headwinds. Then you understand what we're dealing with.

Sometimes things that are not articulated in public shape us nonetheless. They shape the culture and the places that we work and the places that we live, the places that we learn. And I do believe in that Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. quote that I include in the book, that "The mind, once exposed to a new idea, never goes back to its original dimensions." So just by seeing someone else's life, by understanding someone else's thought process, someone else's viewpoint, it's not to indoctrinate anybody or change anybody's mind, but to help you understand the full spectrum of humanity, what's out there. Do I want to engage with the person who has these ideas about privilege? Maybe it makes me think about what does privilege mean? Do I want to think about the person who is put in a certain category because they look a certain way? Do I do that myself?

When you read these stories, you will nod affirmatively in some cases, and you will be shaking your head and your stomach may churn a little bit in reading some of them. But you also may be surprised in reading a story that you think has nothing to do with you and then you think, "Oh, that strikes some sort of familiar chord somewhere. Even though my biography is nowhere in that six words or those backstories, I still am hearing something or seeing something that is familiar to me.”

YD: I must say, a smile played across my face. There's a story in the book a white man is telling about his Black classmate. I believe he's a salutatorian of a white school. And this Black classmate and his white classmates, they all went to lunch. And the owner of the restaurant told the white student that they don't serve Blacks. So the kid, student, went back to the table, told everybody, and the Black student immediately offered to leave. And one of the white students at the table said, "Then let's get out of here." Do you know this story and do you know the name of the person who said, "Let's get out of here"?

MN: Yeah, I do. The person who sent it in was a classmate of President Joe Biden. And before we included it, we actually chased down the story and confirmed that this is a story that has been told over and over again and confirmed. And it makes you think about, can you be an upstander? Would you be the person who would be willing to do this?

I host a podcast, an Audible podcast, by the way, called Your Mama's Kitchen. And it made me think of a similar story from the podcast, in our interview with Conan O'Brien. It's interesting, that podcast is not about race or identity, but almost all of the episodes wind up talking about race and identity. And his mother was one of the first women to graduate from Yale Law School. And then she was one of the first women to work at a very fancy white-shoe law firm in Boston. And as such, when they had big client meetings and big client luncheons and the big room with the mahogany walls and the big leather chairs, she was not allowed to sit in on those meetings. They had her sit outside at a little card table. And much like Joe Biden said, "You know, let's all leave," some of her fellow lawyers said, "You know what? You guys stay in here. I'm going to go have a tuna fish sandwich with her. I'm going to sit outside at the card table with her."

And I love that story because I like to think—I'm a parent. I have three kids. Now a grandparent. Nieces and nephews I'm very close to—I'd like to think that my husband and I are sending young people in the world who would do exactly that, who would be an upstander.

YD: Yes. That was really quite poignant, and I did smile. There's something I want to ask you about breadcrumbs. You have breadcrumbs of your own. I have breadcrumbs. Our breadcrumbs show in the color of our skin. I have cousins who are very fair with hazel eyes. We run the gamut. It's a rainbow. It's not dinner, it's a rainbow. But tell our listeners about your breadcrumbs. It's a story, your grandmother and grandfather, amazing people. And your grandmother. Amazing. Wonderful story.

MN: It's the reason I wound up doing this work, and my first book was a family memoir about our family's very complex racial legacy. I discovered quite late in life that my father had secrets that he just didn't talk about. As a young man after serving in the military, he was honorably discharged from the Navy and returned to Alabama. And that's where he's from, Birmingham, Alabama, and was entering a building on an evening in February, where he was trying to learn as much as he could about the Constitution along with other returning veterans, Black veterans. And they were trying to learn about the Constitution because they wanted to vote. They had just fought in a war against fascism, fought for democracy overseas, and wanted a taste of it when they returned home.

And in order to do that, they had to pass this series of tests if they wanted to register to vote. They had to prove that they knew and fully understood the Constitution. And when he was trying to enter that building, a police officer tried to stop him. And my father, who I've always known as the most mild-mannered, very Zen adult, asserted his right to enter that building. And a scuffle ensued, and my father was wounded when a gun went off. The police officer's gun grazed his leg. And I remember the scars, and I remember the little bit of a lilt he had, just a teeny lilt in his step. It was a result of that wound that he never talked about. And then when I discovered it and talked to my relatives in Alabama, everybody in Alabama knew about it, but no one talked about it. They just, “Shhh! Stop talking about it.”

Listen to Michele Norris Best Sellers

And my mother had her own breadcrumbs in her life. I discovered, again late in life, and from one of my uncles. As they got older, you know what happens: If you're thinking it, you're saying it. Disinhibition. They started telling stories. Another one of my uncles, Uncle Jimmy, who's now gone, told me about my grandmother, my Grandmother Ione's history, my mother's mother, who worked as an itinerant Aunt Jemima. She traveled the country dressed up like Aunt Jemima, going to small towns in a five-state region. She had Minnesota, Wisconsin, the Dakotas, Michigan, and Iowa. And she did these pancake demonstrations at Rotarian breakfasts and Knights of Columbus meetings and county fairs and other functions, where she was heralded almost like a celebrity, teaching people how to use this new thing called convenience cooking. And she was paid quite well to do this, and she traveled, which Black women didn't do.

And because all the connotations associated with Aunt Jemima, you can imagine that people in my family just didn't like to talk about it, to say that Aunt Jemima's quite literally a member of the family. And I did a lot of research around Aunt Jemima and learned an awful lot about the evolution of that fictional character, but also about the army of Aunt Jemimas that were traveling the country. There's a whole bunch of them. I make my living behind microphones. I step on stages and speak to large groups of people. That was not available to my grandmother. She stepped on the stage that was available to her.

"It's not just me reading my stories. It's hundreds of people's individual stories. It's like a river of humanity washes over you when you learn, you listen to people tell their own stories."

And what I learned when I found people who were at some of the events where she would do these demonstrations, and what I learned when I found recordings of her talking about it, is that she would go in and she was supposed to use the slave patois. She was supposed to speak in kind of broken English, and she refused to do that. She was educated, and education was always very important to her for all of her grandkids. And she would walk in and she would speak with a certain diction. And she would focus on the kids in the audience because she knew if they saw a woman of color, a Black woman who spoke and held her head up high and was the center of attention, that it might recalibrate their thinking about what women of color could be in this world.

YD: That's a wonderful story. We can go on and on and on, but we're not today. Maybe you'll come back.

MN: Anytime.

YD: But I will tell you your podcast is very popular here at Audible. Very. And it's fun to listen to. I know something about the kitchen. There's a reason why it's the heart of the home or something like that.

MN: Yes. It's where we become who we are. And a lot of the stories that we share in the book emanate from the kitchen, about conversations that happen there and things that happen there. And I'm so glad that we were able to play clips from the book because I hope people do embrace the audiobook. It is a different kind of experience. It's not just me reading my stories. It's hundreds of people's individual stories. It's like a river of humanity washes over you when you learn, you listen to people tell their own stories.

YD: I want to say thank you so much for a very enlightening time. All the best to you. And listeners, you can find Our Hidden Conversations on Audible. And can I say, it is a truly profound listening experience. It's one thing to read these words and know that these words exist, but it's another thing to hear them in your own ears. It is an incredible experience, sometimes chilling, sometimes warming, and sometimes it's a damn shame, but it's fabulous. Thank you.

MN: Thank you for having me.