Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

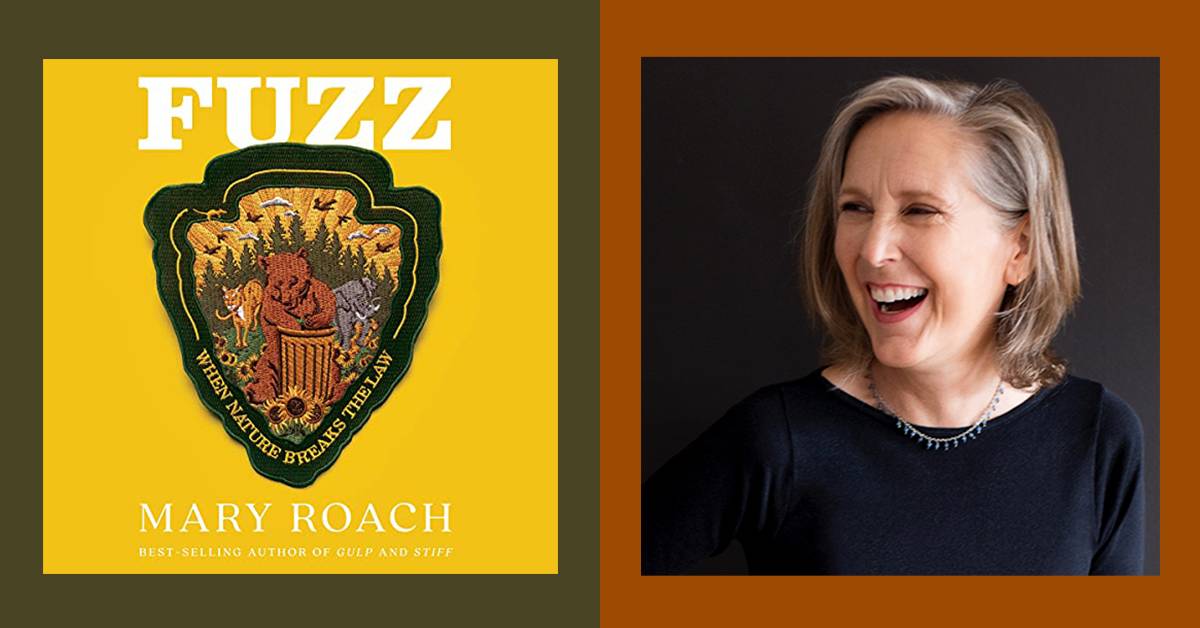

Rachael Xerri: Hello, I'm Audible Editor Rachael Xerri, and today I'm thrilled to be having a conversation with one of my favorite authors, Mary Roach, about her latest book, Fuzz: When Nature Breaks the Law. Mary is a best-selling science author who has also written seven other books, all of which you can get on Audible, including My Planet, Spook, Grunt, Bonk, Packing for Mars, Gulp, and Stiff.

Mary, thank you so much for being here.

MR: Oh, my pleasure, Rachael. Thank you for having me.

RX: In your writing you've explored a variety of topics, including death, space, the digestive system, and war. What inspired the topic of human-wildlife conflict?

MR: It was kind of a roundabout journey that I made to the topic I had actually been interested in. I was in wildlife crime but from the other side, like crimes against wildlife, like poaching and things, because I was up at this National Wildlife Forensics Laboratory up in Ashland, Oregon, where they've got this hair library of all the different types of hair for all these different endangered species because, of course, contraband comes into the country and they have to identify, is this an endangered species? Was the law broken? Obviously the idea of a hair library appealed to me as the weirdo that I am. And I spent some time with this woman who's an expert in telling counterfeit versus real tiger penis, because of course that's something that can be trafficked, and alas, when I was there, the director of the lab said, "You cannot tag along with any investigator on an open investigation. Flat out, no, legally, you can't do it.” And that was the end of that for me because I really love to be on the scene, describing what somebody is doing on their job, and I want characters, I want dialogue, I want like a real-time setting.

So I eventually had the idea of turning it around and looking at wildlife as the perpetrators of the crime, and discovered that there is a whole field of science called human-wildlife conflict. Any time I find a little pocket of science that I didn't know about I get very excited, like this is. There are no books about human-wildlife conflict. Well, maybe there are, but they're like textbooks. It seemed like an area that hadn't been explored in a popular science way. That's a fair summary. There were also some false starts in there. Me landing on a book topic—you don't even want to know. It's like such a frenzied and distressing experience for me figuring out where I'm going to go, what I'm going to do in the beginning. And then I sort it out eventually.

RX: Thank you for sorting it out eventually. As a fellow weirdo, I was so intrigued by some of the adventures and anecdotes that you mention in Fuzz. You talk about tasting mouse bait, you explore the inside guts of a bear, it's some really wild stuff. How do you approach setting boundaries in your research?

MR: I don't think I do really set boundaries. I think that is the role of my editor. I just trust that Jill Bialosky at W.W. Norton, I'm going to hand it to her and if I crossed a line and just take things a bit too far, what she'll do, which she doesn't do it very often, she'll just cross those paragraphs out and write "no." So a couple times she's done that. In this book I don't recall any particular instances of that. But I just plow full speed ahead and put in whatever kind of appeals to me or seems interesting or funny. But she's a good set of eyes to have on the book. She's a little more sensible than I am.

RX: Some of the experts you've spoken to in your research that you write about in Fuzz are really characters, like I could watch reality series about them. Can you walk us through your travel planning process and how you find the experts that you meet along the way?

MR: Yeah, they are characters. They're wonderful. I'm not actually vetting them. I don't ever see them before I travel to spend time with them. Often it's just been, "Hey, I'm an author and science writer and I'm working on this book. What are you going to be up to and could I tag along?" I don't really have a sense of what I'm going to find. So often, almost always, they just turn out to be really interesting people. I know what their job is and I know that it's interesting and surprising. But I never know the quirks of their personalities, and either I'm just really lucky or most people, when you get down to it, are pretty interesting. Often, I just am delighted that they are who they are and that they are that interesting and that they are real characters. Yeah, it's funny, it works out that way.

RX: Definitely. And your experiences are just so rich. How did you possibly condense your adventures into just one chapter each?

MR: It's kind of like a greatest hits album in that I may be there for a day, I may be there two days or a week. And there are moments that happen where I'm taking notes or it's happening and I think, "This is a scene, this will definitely be a scene in the book." A lot of the things that happen the rest of the time are informing me just so that I'm getting up to speed in this world and absorbing as much as I can, so it's kind of background and foundation that I need. But when you get down to it, there's really maybe just two minutes out of the course of a three-day visit that are this amazing scene. Something happened and it was fascinating or surprising or scary or disgusting, and I just know that's going to be the narrative scaffold for that chapter.

"Any time I find a little pocket of science that I didn't know about I get very excited."

So while I need all of the stuff that's going on, or most of it, it's very easy to distill a couple of days of reporting into a couple scenes because there are just those moments where you know it'll be fun for the reader, and that's what I'll end up writing about. It's actually a pretty simple process. The only problem is if I don't have any of those moments. That's a bit of a struggle. Sometimes things are not as fascinating as you hope they'll be.

RX: Although it doesn't feel like you cut back on any of the details, was there anything that you did have to cut out that was really fascinating that you wish you could have shared with all of us?

MR: In the beginning you asked me how I landed on this topic, and some of that material from the Wildlife Forensics Lab, some of the cases they were working on, I initially wanted to kind of cram in that world as well, but it seemed too messy and I liked the neatness of going crime by crime, you know, murder, manslaughter, home invasion, jaywalking, trespassing, littering. The whole spectrum of crimes was a nice way to organize it. To bring in, say the hair library and the tiger penises, it just didn't fit. Sometimes you just have to let it go.

RX: This is your first time narrating your own book, and I just have to say you are so witty and funny. I really felt that your writing voice carried into your performance. Can you tell us how the recording experience was for you? How did you prepare? How did you feel reading your own book?

MR: I'm glad to hear that because it was my first time and I had a lot of insecurity about doing it myself. My other books have been read by professional narrators. These people have trained for this, they know the breathing, they know how to keep their energy level up. There are things that they do that I don't know how to do, and I didn't prepare because I didn't know how. Short of taking a class, I didn't really know what I could do, so I just showed up at the studio with a certain amount of trepidation. But I had this wonderful director, and this was during COVID so he was in LA, he was basically just in my ears. The [people at the] studio were really fun and really patient and had great senses of humor.

After a couple of hours, I had no more trepidation and it was actually a lot of fun. I would absolutely do it again and I wish I'd done my past books myself. Not to say that the people who did them didn't do a good job; they did do a good job. The only thing is that because I'm a character in my books to a certain extent, people have my voice kind of in their head when they read, and I think they want that voice to match a little bit and they are sometimes disappointed. So I was glad that that element was there, that at least my voice speaking matches my voice in the book and in my head. It was really fun. It's a lot of time for, what is it, 300 pages? But it went by really quickly and I'm really glad that I did it.

RX: Did you learn anything about your own writing while you were narrating?

MR: I was very much aware that when I write a book I'm writing to be read. So when I read it out loud, I'm thinking in my head, "You know for the audiobook I'd probably skip that paragraph. That's too technical. I'd skip that just to speed it up a little bit." Not that I would necessarily change the book, although reading out loud makes you aware of things that you feel like you could have left out because you just get impatient a little bit when you're reading. But [it] mostly just made me aware that they're very different media, and I could certainly imagine the people who do an audiobook first that that's a very different approach. You know you've got the attention span of somebody listening who is holding a certain amount of material in their mind [and] can't flip back to the page before and say, well, who is this or where are we?

It's interesting to think about the different experience for the reader or the listener and how sometimes when you're reading something aloud that was written to be read, you're thinking, oh, this is too much detail or, especially for me, I have these footnotes, people love these footnotes because they're kind of quirky. They're stuff I couldn't shoehorn in, but they absolutely derail the narrative for a spoken chapter. So we put them at the end. We recorded them all at the end, but I very much was aware that that's something a reader can choose to do, look down at the bottom of the page and go back up, reread a sentence, get the flow back in their head. But when you're listening, you just derail people by going, "Oh, footnote. Hold on, footnote." And then you go back to the text. That just doesn't work. That was definitely something I was aware of.

RX: In Fuzz, you give examples of animals adapting to human environments. What are some ways you've observed animal intelligence adapting to human interaction and what do you think the implications are of that?

MR: The animals that we tend to come into conflict with, not just in urban areas but like in bear country, these are smart animals. They have figured out that people eat and have food and that that food is sometimes pretty easy to get to. They will apply a surprising amount of ingenuity in getting to our food supply. There are special double-locking garbage containers designed to keep bears from getting into dumpsters. In the building code in Colorado in Pitkin County, where Aspen is, the building code prohibits using French door handles on your decks because it's so easy for the bear to just push it down and lean in. And the bear is in. Even a hollow-core doorknob, you're not supposed to use those because the bears can crush it with their teeth, turn it, and enter the house.

"...Most people, when you get down to it, are pretty interesting."

It's amazing the ingenuity that these animals apply. The more intelligent and adaptive the creature, then the more vexing it is for us. Animal intelligence makes this whole world more challenging. Like elephants, for example. People have thought about, "Okay, all we really need to do to keep elephants out of this area is to put up a big electric fence." But the elephants are smart and they'll figure out, okay, the wooden part, if I touch the wooden part only, I don't get shocked. So one elephant will take his or her foot and push down the whole fence, which is easy for an elephant. It's an elephant. Push it down and let the others step over. Any time we come up with a "solution," usually pretty quickly the animals figure out a way around it, so you just have to keep trying to outsmart them and it's a full-time job.

RX: Where do we draw the line on how much we control and govern animals? How involved do you think we, as everyday citizens, should be?

MR: In this country a number of things are happening when an animal is put down because of a conflict. It's often because it's a large animal that has harmed or killed a person. In this country and in Canada, that's the way things go. If the bear has become aggressive or has harmed someone, the policy is to destroy that animal. There are instances where a wildlife agency has said, "Look, let's just monitor this situation. Let's not act too quickly. Let's see. Maybe it won't be a problem. Maybe we can move this animal into the woods in a different place." But the issue becomes liability. If you as a wildlife agency decided to monitor that animal and to not take action, or you moved it to a wooded area X miles away and it made its way into a human community and caused harm to somebody there, then you as the agency have to worry about a lawsuit. There have been some multimillion-dollar payouts because that very thing has happened.

As with so many things in our society, there's an undercurrent of liability concerns. The public opinion does sway things. Particularly with beloved animals like bears and cougars, there's a lot of support for not immediately destroying an animal. There's a region in California where there's sort of a two strikes—or is it three strikes? I forget—law. So the animal isn't destroyed unless it's repeatedly causing significant problems. It's a tough question to answer.

RX: Now, you mentioned public opinion, and it seemed like the entire country learned about the dangers of domesticating wild cats while watching Tiger King last year.

MR: Yes.

RX: And at the same time, people are posting dangerous videos of animals on social media just to get likes. I'm curious to hear your opinion about the effect that pop culture has on nature and vice versa.

MR: I think it has a tremendous effect. There are so many people now wanting to take selfies with bears in Pitkin County, where I was in Aspen, Colorado. So many people, when a bear comes into downtown, which it does with regularity a lot of times at night but even during the day, enough people want to go up and take a selfie with a bear that that is now illegal. You will be fined. The fact that there had to be legislation to keep people from walking up to bears to take selfies is fairly astounding, and it self-perpetuates because people see those and they see that they got a lot of likes and they go viral and people want to have a viral video. Any time you bring people and bears together you're heading down a dangerous path, dangerous usually for the bear, occasionally for the person.

People have this idea either they're these rogue, crazy predator monsters or they're teddy bears and you could walk right up to them and take a selfie. I think actually the latter is more damaging for the bears. But that tends to be where we get our information and our concepts of these animals, what they're like and how they behave.

I mean, I had an idea of elephants as gentle, lumbering, harmless animals because I grew up with Babar and Dumbo. And then I spent time in India, where 500 people a year are killed by elephants, often just because they're so big and they step on you or knock you over. It's not that they're coming at you and strangling you with their trunks or anything. It's important to counteract some of these false beliefs that are generated by childhood books, and these days social media has a tremendous amount of influence.

RX: I would love to hear you expand on that. You mentioned Babar and Dumbo. What do you think the implications of animated characters—I'll list a couple more, Smokey the Bear, I'm also thinking even of YouTube videos, we see Koko the gorilla, who can communicate with people, we see videos of elephants painting, for example, or even shark week images—what do you think the implications are of all of those images in the media and how we approach those animals either with comfort or with caution?

MR: In all of those cases that it does influence how we feel about them. I know that because of my impression of elephants, based on nothing to do with real elephants and everything to do with childhood books and cartoons. When I got to India and I was traveling with a researcher from the Wildlife Institute of India and we got to this place where there's a lot of elephants, and right down the road from where we were staying, there was a traffic sign that said "Danger: Elephant Crossing Area." And when we got there, it was evening, around 6 o'clock and right after we ate, I was like, "I want to walk down to the elephant crossing to see what's going on." And they're like, "We're coming with you." It was sort of this sense of, like, "Are you out of your mind?"

Even though I knew the statistics, I couldn't set aside this idea that they're elephants, they don't kill people. I just wanted to see one and I wanted to be near one. And even though I knew rationally that that was a dangerous thing to do, I couldn't set it aside. I was like all right, let's go, and they were very uncomfortable. We walked down to the road and we spent maybe five minutes kind of standing around. One of them said after about five minutes, "Let's go back inside now." Because this is what they do. They know elephants and they know what happens when people get too close to them. It's very hard to combat these impressions that we have.

I remember writing about the efforts in World War Two to develop a shark repellent for fighter pilots who had to bail out from their plane over water or when a ship was sunk and people were in the water and, you know, life jackets. There was a tremendous fear of shark attacks. It's super rare that it happens. The reason that they came up with the shark repellent—really it was more like they call it a pink pill— something to give these men so they feel like they're safer. People didn't want to be pilots because they were afraid that if they had to bail out, they would be devoured by sharks. Well, sharks, they don't do that. I mean, occasionally they'll see a person and they'll take a bite, thinking "maybe this is something I like to eat," but then they find out, well, it's not. But, of course, one bite could kill you.

I remember asking when I reported this chapter, I talked to a man who is an underwater videographer and I said, "What is your best piece of advice for somebody who's scuba diving or snorkeling and then encounters a shark?" And he said, "Enjoy the experience." As with bears, people do die in shark incidents. I should say it's often not really an attack, just like it's a tasting. But we have this primal fear.

RX: Absolutely. Thank you so much for sharing your insights. So we're at our last question: Which animal-human encounter made you laugh out loud the most?

MR: Oh boy. I have to say it was things in the macaque chapter in India, the monkey chapter. The monkeys themselves, the things they get up to. For example, there was some monkey that got into a medical institute in New Delhi. It would go along the hallways and it would pull an IV line out of someone's arm and then suck the glucose like a kid with a straw and their soda pop. The macaques, they like areas where there's trees, and that tends to be the well-to-do parts of New Delhi. They're in the halls of Parliament, they're in chambers where court proceedings are going on. They're everywhere, and they're very vexing for people who have to deal with them day to day. But for me, they were hilarious. So many encounters in that chapter just cracked me up.

RX: That chapter was so laugh-out-loud funny, and there were so many moments in Fuzz that were jaw-dropping.

For everyone tuning in, please go to Audible.com/Fuzz to get a copy. You won't be disappointed. Mary, thank you so much for speaking with me. I had a blast.

MR: Oh, me too, Rachael, thank you so much and thank you everybody for tuning in. Have a fabulous day, everybody.