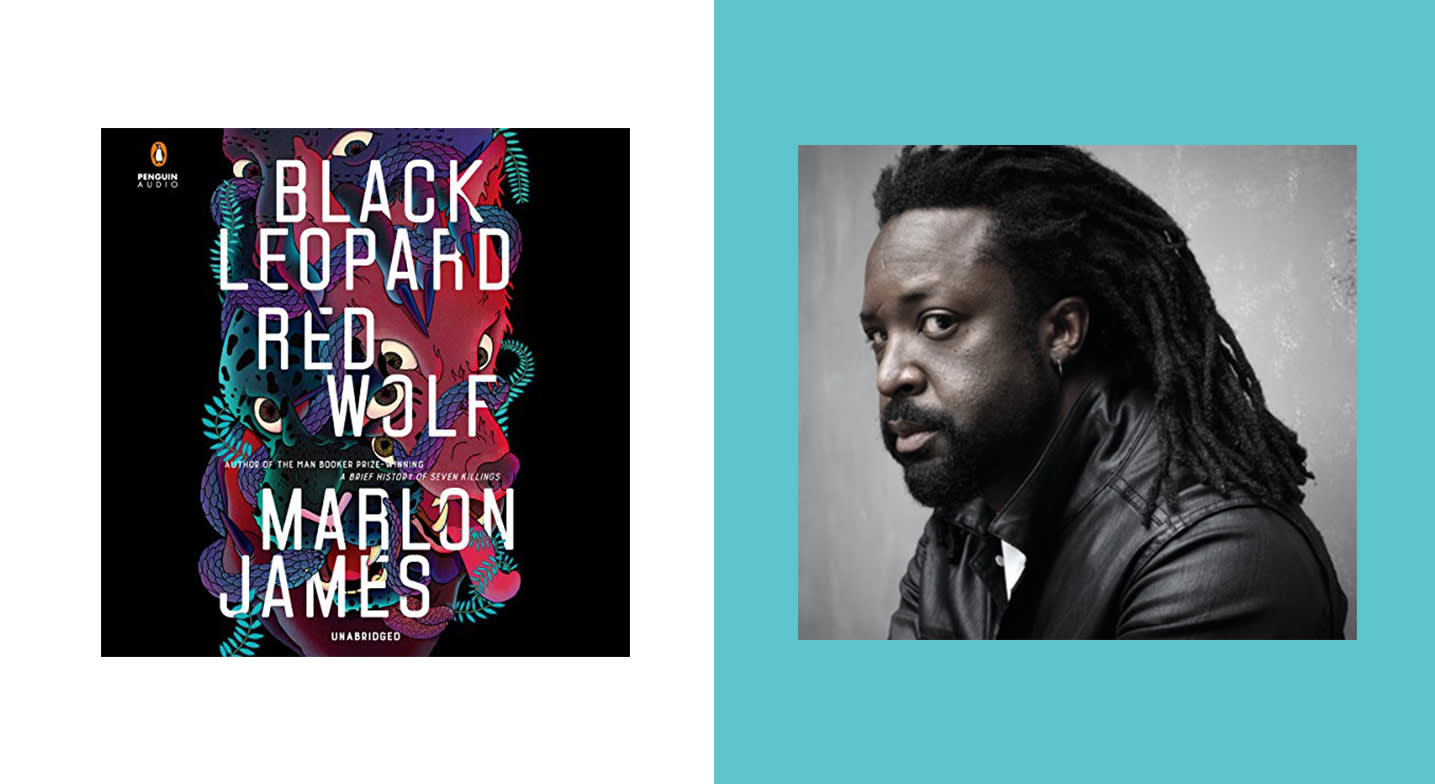

From the moment the world heard that award-winning author Marlon James was setting out to create the African Game of Thrones — whether he made that claim himself or not, we waited in anticipation. And it’s been a great joy to find that the first book in the epic saga, Black Leopard, Red Wolf, is riveting and well worth the wait. In every minute there is a new threat, a new scheme, and a new astoundingly unique voice; be it beast, witch, demi-god, or amorphous liquid assassin. And the combination of James’s enrapturing writing and narrator Dion Graham’s exquisite delivery makes it a transcendent force.

Listen in as James and Audible Sci-fi and Fantasy editor Sam Danis talk about this exciting new work, why Graham was the number one pick for the job, and why story dictates that the next installment will likely find a new voice.

Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

Sam Danis: Hi, I’m Sam, Audible Sci-fi and Fantasy editor, and I’m thrilled to be chatting today with Marlon James. He’s the author of four novels, including The Book of Night Women and The Brief History of Seven Killings, which won the Booker Prize in 2014, and, of course, the novel we’re here to talk about today, Black Leopard, Red Wolf, the first in an epic fantasy series. Welcome, Marlon, and thanks for taking the time.

Marlon James: Thanks for having me.

SD: So, I’ve been listening to the audiobook for Black Leopard, and what strikes me most about it is really how much of an oral history it is. Your protagonist, known as Tracker, is narrating his story to a character called The Inquisitor…

MJ: Right.

SD: And then nestled within that story are other stories that kind of organically spring up, and so on and so forth; I’m curious how much you considered the performance or the auditory element of this story as you were writing it.

MJ: It was pretty much the only thing I considered, for lots of reasons. All the ancient stories regardless of culture, whether it’s the African epics or the Iliad, were written to be read aloud.

SD: Right.

MJ: For a long time, none of these stories were written. We didn’t have writing. The Iliad existed before it was written, as soon as I realized that I was writing a story that I wanted in the vein of those epics, those stories that took place hundreds if not thousands of years ago, I knew it had to be read aloud. I knew it had to read like prose that could be read aloud. Most of the sentences, I read aloud to myself, and for some extra torture I had other people read it to me, because, for me written was important, balance was important, volume is important, and I do think of volume when I’m writing. Some scenes are a whisper, some scenes are a shout, some scenes are laced with happiness, some are laced with bitterness and regret.

SD: Right.

MJ: Even if the person is not reading it aloud, I want sound in their head. So, it was very, very important. It’s also in the first person. It’s an actual person giving testimony, so voice, and volume, and pitch, and tone, and mood, all that was extremely important.

There are things your eyes will forgive that your ears won’t.

SD: That’s really interesting. Did you do any rewriting based on what you heard aloud, either when you read it or when someone would read it to you?

MJ: All the time, because there are things your eyes will forgive that your ears won’t. There are things that on the paper still looks like a perfectly fine word and then you read it, it has no volume, like a palpable energy. If I were to just say, look at the words they’re using, particularly the verbs and the adverbs and give it an energy rating, from say from 1 to 5 — 5 being the most vivid, the most vibrant, the most active, and 1 being the 1 that conjures the least amount of sensory image in your head — and I say, “lacerate,” that’s probably a 5.

SD: Right.

MJ: “Shout” is probably a 4. “Whisper” is probably still a 4 because even if it’s quiet, it’s shrinking the sound around you. What would you give “obtain” or “manage” or “ponder?” So if you’re going to say those words you don’t even realize that you’re sapping the energy of your own sentence. Because it’s a perfectly fine word to say “commodify.” I’m pretty sure no image went off in your head a while ago when I said that. It’s like me saying “I will overturn this verdict.” Lovely. But if I say, “I will drop like an ocean in this court”…

SD: Wow.

MJ: This is from The Crucible. It’s a totally different thing, and I do think about that volume and did the word take up space and did the word have mass when I’m writing it.

SD: That’s really interesting and that’s great for us to hear as audio nerds because I think for us a lot of the experience of listening to a book is really getting that emotion.

MJ: Yes.

SD: And I think your work in general really lends itself kind of perfectly to audio. In The Book of Night Women, which is performed by the incredible Robin Miles, Lilith narrates her story in authentic dialect. And in A Brief History, which had more than 70 characters, many of those characters spoke in Jamaican patois. What do you hope listeners notice in the narration of your stories that maybe they would or wouldn’t pick up on in simply reading?

MJ: I think in listening they pick up tone and they pick up mood, and think sometimes that might be hard when you’re just looking at words. It’s as though sometimes a word in a foreign language you understand it because of the tone in which somebody said it.

SD: That’s very true. Yes.

MJ: I think that audio has that advantage in that even something that is not necessarily plain can be translated because of tone and symbol and voice, and I think, that’s one of the things I hope that people pick up with audio. One of the interesting commendations I got for A Brief History was from the Royal Society for the Blind in the UK.

SD: Oh wow.

MJ: People forget blind people read too.

SD: Yes, of course.

MJ: Audiobooks are a lifeline for the visually impaired. You really appreciate how much the book depended also on sound as opposed to just visual details which someone who’s always been visually impaired would never understand. So whenever they’re talking about that black dress or the color red. If I was born blind, that has no significance for me.

SD: Right.

MJ: So, again it comes back again to sound and to volume and I do want readers to feel that.

SD: That’s great. Do you ever listen to any particular recordings, audiobooks or otherwise, or even your own audiobooks to get influence into how your characters’ voices and cadence will sound?

MJ: I think I listen to audiobooks mostly for enjoyment actually.

SD: That’s fair.

MJ: One of the reasons why Dion Graham ended up voicing this is that I just loved Evicted.

SD: Oh yes.

MJ: It certainly increases my yearly reading volume, at least double. I think, particularly with folktales, there’s again meaning is conveyed in how something is said, and I think audio particularly reminds me of that. Particular if it’s audio of my heroes whom I’ve read countless times. I’ve read Toni Morrison a million times, and the audio is still a revelation to me.

SD: Right. That’s always such an interesting experience for us when we read a classic a million times but for the first time we get to listen to it, it takes it to a whole new height.

MJ: Um-hmm. Yes.

SD: So you mentioned your narrator, Dion Graham, who is a bit of an audio legend, to say the least. He’s actually part of our Narrator Hall of Fame here. Did you have any part in choosing him?

MJ: What?!

SD: Yeah. He is.

MJ: I pretty much chose him instantly. Somebody sent me his recording of Ishmael Beah’s [Radiance of Tomorrow], and that alone sold me because I think sometimes when people are trying to do an African voice, they just try to sound like Nelson Mandela, which is perfectly fine. No, he just has so much dynamics and range and then on top of that Dion raises the standard. I’m like, dude! There are parts where there’s Gibrilla who’s a musician, and he sings the parts.

I knew I was going to write in English, but I wanted a very non-English-sounding English, and research helped a lot in that way.

SD: Yeah.

MJ: I’m like, “Dude, you’re making it hard for me, man. Everybody’s going to expect me to sing.” I didn’t have to think twice. The second I heard it, I said, “That’s the voice.”

SD: That’s awesome to hear, and he does an amazing job with this recording, all the different accents and voices. Did you work with him directly on any of it?

MJ: He would run things by me every now and then, but not necessarily directly because we were working pretty fast on getting the book out, but he did run many things by me, including, he picked up one glaring proofreading error that got fixed in the nick of time.

SD: Oh, wow.

MJ: He said something like, “I don’t know how to read this”, and I went, “That’s because it’s an error”. Oh, my god. We had to go all the way, the Americans couldn’t figure it out. They couldn’t track down the person. We had to call the editor in Canada. The person in Canada called the printer.

SD: Wow.

MJ: It’s like, “Man, Dion, I owe you. I owe you big.”

SD: As a copy editor myself, I appreciate that. Go, Dion!

MJ: Right, but again, the eyes will miss things that the ears won’t. He’s reading it, and it just doesn’t sound right to him.

SD: Right.

MJ: Whereas everybody passed it. It went through four editors, including me.

SD: Right. That’s amazing.

MJ: It was just a comma, one comma.

SD: Goes to show the power of a comma, even in audio.

MJ: Yeah. I was like that pause isn’t right.

SD: Right. I read that you did a lot of research on African language, mythology, history, storytelling, in your research for this book. Can you talk a little bit about some of the ways that rich history played into your dialogue and structure here?

MJ: Absolutely. For one, the research changed a lot of the book. At one point it felt like the book was writing me. I know I wasn’t going to exoticize African languages, but I did know that I wanted the sort of rhythm and pace and even the sort of vocabulary system of non-English languages, even though I was writing in English.

So, for example, in my world 10 and multiples of 10 are the highest number so there is no 11, it’s ten and one. There’s no thirteen, it’s 10 and three. They’re not going to say a hundred and ninety-three. They’ll probably say a hundred and nineties and three. Or, in some languages, the verb is always present tense, regardless of tense. That’s actually how Jamaican English is as well. We don’t say “He went,” we say “He did go.”

SD: Right.

MJ: And we don’t say “He’ll be going soon.” We say “He soon go.” So that affected the language, because I knew I was going to write in English, but I wanted a very non-English-sounding English, and research helped a lot in that way. Of course, there’s also the historical details in the sense of geography and the folklore, the myths, the legends, the things that they’ll for granted. All of that played into it, but the research was, I mean it was two years of research. Because I knew I had to get certain sort of the pitches and tones right.

SD: What specific languages did you study, can I ask?

MJ: I looked at Wolof quite a bit. Wolof more than nearly anything else. I looked at Fon. I looked at Twi because a lot of Jamaican English Twi. What else? I was also drawing proverbs from dozens of languages. Thank god I made notes somewhere because I might have forgotten.

Swahili. In fact quite a few of the proverbs in the scenes are in Swahili. Yoruba, and so on. I drew from pretty much everywhere.

SD: That’s interesting. My husband is a linguist. He studies a lot of African languages so I had to ask.

MJ: Oh, really.

SD: Yep.

MJ: Oh, wow. He’s going to pick up all the errors that none of us picked up.

SD: Yeah. He’s really looking forward to listening. This is the first in a planned trilogy, and you’ve explained that subsequent novels will tackle other characters telling the same story from their perspective.

MJ: Right.

SD: I’d love to hear your thinking behind this structure and how you see those three distinct versions coming to a head because I think this is a really interesting way to tackle a trilogy.

MJ: Yeah. I’m trying to remember how it came about. It came about because I was talking to somebody about a TV show that showed different perspectives, and I remember that person telling me what a great idea it is for a TV show, and I kept thinking, “Forget TV. That’s a great idea for a novel.”

SD: Right.

MJ: I knew the story was more than one book, but I didn’t quite know in what way, and I also wanted to write it in a way that I wouldn’t get bored because I write the way I read, and I have a very limited attention span.

What was incredibly convenient is that a lot of African storytelling is that way. For one, it’s a trickster that’s usually telling the story, so you already know to maybe take this with a grain of salt, and instead of a story going from part one to part two to part three, when my grandfather, for example, was telling a story, every night it would be basically the same story with a tweak to it. Or the same story with somebody else, whether it’s Anansi, Anansi and the duck, and the first day the story’s from the point of view of Anansi, and the second is from the point of view of the duck. The third is a point of view from a bird who was flying by and saw it all happen. So, the story sort of moves associatively instead of in a linear way.

SD: Right.

MJ: It just all sort of clicked and made sense as soon as I realized that the story’s almost moving sort of crossways instead of from beginning to end.

SD: Right, and you even get a little bit of that, in this novel there’s a part where a story’s being told, and every time it’s told, there’s a slightly different variation to it. So, it’ll be interesting …

MJ: Yeah.

SD: … to hear the whole thing retold.

MJ: It’ll be interesting for me to write it.

SD: I’m sure. Do you know yet if we can expect to hear different narrators for the different perspectives to come?

MJ: Probably because the next book is being told by a woman, being told by an old woman.

SD: Oh great.

MJ: By an older woman, rather, so it’s going to be interesting. I remember thinking, man, Cicely Tyson would just rule on this or Grace Jones.

SD: That’s awesome.

MJ: See if I can start publicly lobbying for Grace Jones. I’ll see if she will notice me.

SD: So your distinct style which is challenging and lyrical and unafraid to shy away from violence and the erotic is very much here in this novel, but it is a completely different genre from your previous work. I think you’re a self-proclaimed fantasy nerd, and you’re certainly in good company. Did you always intend to write in this genre and what’s different about the experience for you?

MJ: I think I always knew I was going to write in this genre, even if I didn’t look at it as necessarily a genre. It doesn’t look like a genre shift for me mostly because I’m such a fan of fantasy and I grew up reading and watching so much of it.

SD: Right.

MJ: And also, all my novels have had some sort of, kind of supernatural, fantasy, or spiritual or just surreal element to them. My last novel, a lot of people considered as a super-realistic novel, forgetting that the first narrator is a ghost. So to me it always felt like the logical progression, but I also, as somebody who never forgot the myths and legends that I grew up with. I just knew that sooner or later I was going to write something influenced by that and in response to that. To me it’s like rock and roll musicians, eventually they have to reckon with the blues. For me, I knew that eventually I’d have to sort of reckon with the myths.

SD: Right. That’s interesting. Did you have any of these kind of fantasy stories read to you specifically?

MJ: Other than my grandfather telling me stories, not really. So my background in fantasy is pretty much whatever I could find at the pharmacy or whatever I could beg, borrow, or steal. Most of the major books of fantasy I didn’t read them until I was an adult, because there would be no way of me getting access to these stories. I have a very sort of pop history in fantasy. In fact, most of the fantasy films which are part of my growing up, for instance, Dragonslayer. I didn’t realize that I’ve never seen the film. I just read the novelization.

SD: Oh, that’s interesting.

MJ: Which for some weird reason was easier to get than I think in the cinema, because the cinema was in the city and I didn’t live in the city. I lived pretty far away from the nearest theater. But somehow a pharmacy would have Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan the novelization, and I’m realizing that almost my entire sci-fi universe was movie tie-in novels. I mean I read Superman III. It’s kind of funny, so I tell you my fantasy background is not very lofty or deep at all. It’s all pop. It’s all whatever was in the pharmacy, whatever my richer friends dumped in the classroom, whatever I found on the street or when a friend’s parent had passed out.

SD: Right. That’s really interesting, and I can definitely sympathize. I feel like I maybe started a little bit the opposite way with movies and TV, and now I still feel like I’m catching up on the classics a bit. So, talking a little bit more about fantasy, you’ve offered your frank critique of the lack of diversity in the genre, and even in contemporary works, and now you’re getting comparisons to Tolkien and George R. Martin. What does it mean to you to add your voice to the fantasy canon?

MJ: For me, I don’t know if I set out to make a difference or set out to correct something. I just set out to write the kind of book I always wanted to read.

SD: Right.

MJ: I think people should write the books that they want to read, that might not be out there. That’s one of the great things Toni Morrison said. In terms of what that might mean or that impact, I’m not really sure because there’s a lot of writers out there. It’s not as if I’m some sort of lone orphan in the genre.

SD: Right.

MJ: Sofia Samatar has been writing stuff for years. Kai Ashante Wilson or N.K. Jemisin, or Nnedi Okorafor.

SD: Yep.

MJ: There’s some really, really fantastic work and fantastic fiction that’s already happening. If anything, I’m kind of late, but I didn’t think about that either. I just wanted, again, ultimately your reasons for writing, if you’re really going to write, have to be personal. The motivation has to come from within you to keep going, and for me, I wanted to geek out on a world where people look like me.

SD: Yeah. I love that. Well, we certainly enjoyed listening to that world, and very much looking forward to the next two novels to come. Can you give us any sense of when book two is on its way?

MJ: You see, if I tell you now my editor is going to call me and go “I noticed you promised…”. I’m certainly trying very hard for every two years. I’m trying to stick to that schedule, and I know my publisher’s going to go “I heard you said two years. I’ll be checking.”

SD: Well, we’ll try to be patient. I’ll be very excited to see what voice we can expect for book two as well.

MJ: Me too. It should be exciting.

SD: Thank you so much again, Marlon. It was great taking the time to talk with you.

MJ: Thank you.