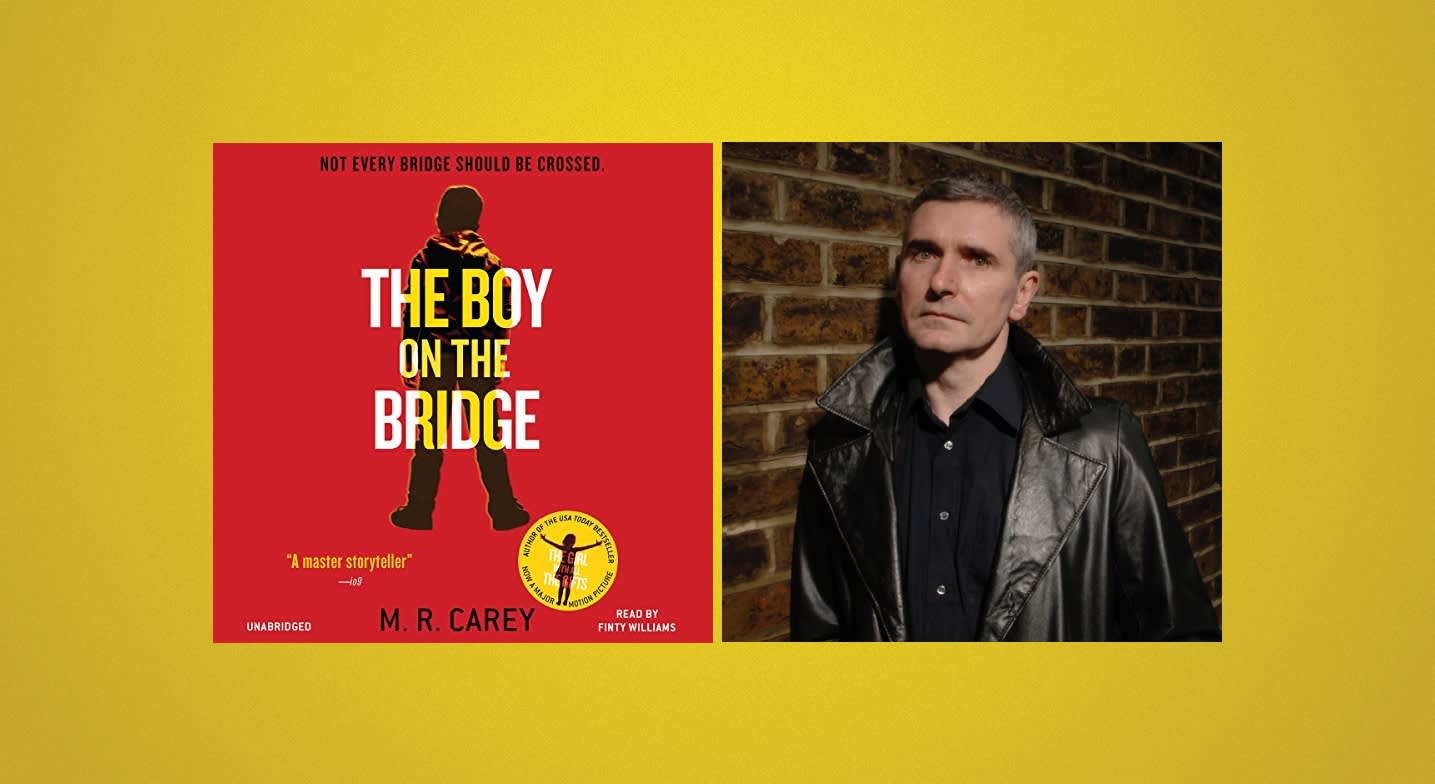

Three years ago, a little book called The Girl With All the Gifts burst onto the scene and immediately captured the attention of just about every editor on our team. M.R. Carey stunned us with a fresh take on the zombie-apocalypse genre, which, as of then, seemed to have been executed in just about every way imaginable. Add to that a pitch-perfect performance from Finty Williams (Dame Judi Dench’s daughter BTW), and it became immediately clear that Carey was an author to watch; a name that we’d eagerly search for with each season’s batch of new releases.

Now, nearly three years to the date after the publication of that book, Carey has returned to his post-apocalyptic world in The Boy on the Bridge, a thrilling and satisfying follow-up (or prequel, depending on how you look at it) to the story. Officially a mega-fan, I was excited to have the chance to ask the author about his influences, his writing process, and of course, how he came to find such an incredible voice for his novels.

Audible Range: What authors and books have most inspired you and your work?

M.R. Carey: That’s a long, long list! The very first writer I ever got seriously addicted to was Enid Blyton, and I would have been about five years old. I discovered the Magic Wishing Chair stories, and then shortly after that the Faraway Tree series. They’re written in a very plain style but they’re full of great ideas and for a kid of that age they were just completely immersive — and they gave me a lifelong taste for fantasy.

In my teens I worked my way through all of Michael Moorcock’s Eternal Champion books, of which there were close to fifty, and then I graduated to writers like Mervyn Peake, Roger Zelazny, and Ursula Le Guin. Le Guin has been a huge influence. I think she was the first writer I discovered whose stories were interrogating the real world through fantasy tropes. More recently I’ve read China Miéville with huge pleasure, and I think he’s changed my perceptions of how you can embed political themes in a genre story.

And all through that time I was reading comics, too. There’s a trinity of great British writers whose work I both admired and emulated. The three are Neil Gaiman, whose mark on my work I think is really obvious, Grant Morrison, and Alan Moore.

AR: We are huge fans of The Girl With All the Gifts and really enjoyed the nods back to that story within The Boy on the Bridge. It occurs to us that these really could be listened to in either order.

MC: I tried to make The Boy On the Bridge as freestanding and self-contained as I could, but within that I very definitely sneaked some sidelong glances at The Girl With All the Gifts. There are Easter eggs that are intended to be picked up by readers who are familiar with the earlier book, some small and some quite significant.

“She animates the story so it feels as though you’re watching and listening to a drama playing out in front of you.”

AR: How involved were you in the casting of Finty Williams for your novels? Is it fair to assume she is your preferred narrator by now? (We certainly can’t get enough of her!) What do you especially admire about her performances?

MC: The decisions are all made by my publisher, but they consult me and they like me to be happy. I remember that when they were choosing a narrator for Girl they sent me samples from about a dozen narrators. Finty [Williams] stood out at once, and she was my first choice — but she was everybody else’s first choice too! Since then I’ve always asked if we can get her back, and fortunately she enjoyed Girlenough to say yes.

I think what I love most about her reading style is the very vivid sense you get of a varied cast. Each voice is different and each voice is freighted with personality. She gives everyone a real vector, a real weight, so when they clash it means something. Her readings are dramatic in the fullest and best sense of the word: She animates the story so it feels as though you’re watching and listening to a drama playing out in front of you.

Yeah, you can definitely say that I’m a fan!

AR: You started out writing urban fantasy (the Felix Castorseries) under the name Mike Carey. How did you make the switch to horror/supernatural/sci-fi thrillers? Any plans to return to the genre of urban fantasy?

MC: I’ve never wanted to stick to writing just one kind of story. I switch genres, I switch media, I try to make each new thing different rather than recreating the previous thing with the furniture reupholstered. So the Castor novels were all of a piece, but they were very different from the twonovels I co-authored with [my wife] Linda and [our daughter] Louise. And then The Girl With All the Gifts was different again. This all happened while I was writing a ton of comics, too — superhero books like X-Men and Suicide Risk, dark fantasy with Lucifer, horror with Hellblazer and Rowans Ruin.

So I don’t feel as though I have a home, in terms of genre. I have a very wide comfort zone. What I can’t do, and don’t think I’ll ever be able to do, is realist fiction. I need there to be fantastic or uncanny elements in the mix. I don’t know why that is, but it’s true. The few times I’ve tried to write outside of the speculative fiction umbrella I’ve felt like I was painting in white on a white canvas. It was too nebulous. I know that’s a fault in me, but I’ve learned to accept it.

AR: In addition to being a best-selling novelist, you’re also a pretty prolific comic book writer. How does your comic book work play into your novel writing? At what point in your planning process do you know when a story is meant to be visual vs. read and heard?

MC: I love the comics medium for its own sake, and I love writing comics. But there’s no denying that it was through comics that I actually learned to write. This isn’t to say that comics writing was just an apprenticeship for other forms of writing. It really wasn’t. I still write comics and I hope I always will. But until I’d written for comics I’d never seriously thought about structure. Comics writing forces you to focus on decisions about pacing, transitions, the length and positioning of scenes — because your canvas is very limited. Twenty pages in an American comic book, an average of five panels per page, and probably no more than 30 words of dialogue in the average panel. There are formal constraints that you have to steer into, and you fall apart if you don’t take them seriously. So after writing comics I had a better idea of how to use the freedoms that the novel gives you.

When it comes to choosing a medium for a specific story, I’m absolutely flexible. Most stories, if they work at all, will work in any format. There are exceptions, of course. A Felix Castor comic book would hit a serious hurdle in terms of how to present his music on the page. I’m sure you could do it, but you’d have to invent a visual vocabulary for it. A few musical staves wafting across the page wouldn’t cut it.

AR: It also begs the question — as an author whose work definitely falls under the umbrella of horror and ghost stories, and whose stories feature kids: Did you have any ghostly encounters as a kid?

MC: Not personally, no. And I’m a serious skeptic when it comes to the paranormal. But my mum used to see ghosts everywhere. There was a haunted bed in her first marital home. Before that, another ghost stole her underwear when she was in her teens. The last house we all lived in as a family had the ghost of a vicious old lady who threatened to “bury the lot of us.” I never saw any of these apparitions, and I’m not sure I ever believed in them, but they made sensational stories. And probably they were as important as Enid Blyton in pushing me down the career path I eventually chose!

For more with M.R. Carey, check out last year’s Audible Session with him.