“What did you see?” is a legitimate question to ask a friend who just attended a movie. But the image projected onscreen is just one component of a movie’s sensory richness. If you asked the same friend “what did you hear?” you might get a more complicated, more revealing answer.

Masha Tupitsyn, a New York-based writer, teacher, and artist, is an attentive and obsessive archivist of the artistic fragment. In books like Laconia: 1,200 Tweets on Film, and on her indispensable Tumblr, she is constantly isolating the words, images, and sounds that stimulate a deeper, more meaningful engagement with pop culture and visual art.

Love Sounds, her latest creation, is an audio history of love in the movies, and the final part of what she calls an “immaterial trilogy.” In its ideal form, Love Sounds runs as a 24-hour installation — which was completed in 2015 — although Tupitsyn has also created a four-hour version (a preview of which is below), which has screened at MoMA PS1, The Kitchen, at Los Angeles’ Cinefamily theater, and across several countries. The approximately 1,500 audio clips are drawn from English-language movies — many familiar, some obscure — made since the 1930s and the birth of synchronized-sound “talkies.”

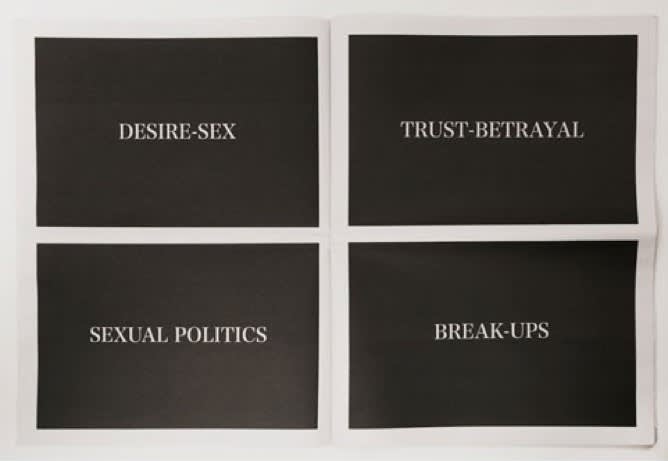

Unlike Christian Marclay’s celebrated 24-hour epic installation The Clock, Love Sounds withholds (or “dematerializes”) the images of the films it samples, leaving viewers to either paint from memory or imaginatively overlay these scripted pop-cultural sounds with a more personally resonant set of visuals. The only image Love Sounds gives us is a black screen with white titles that gesture toward each chapter’s organizing principle: HEARTBREAK, or FATE-TIME-MEMORY, or TRUST-BETRAYAL.

The work is emotionally rich, politically charged, and at times, almost unbearably intimate. Tupitsyn told one interviewer that Love Sounds is “as much my autobiography as it is everyone’s cultural archive.” Recently, Tupitsyn spoke to Audible Range about why “listening is the only critical practice left.”

Preview of the four-hour version of LOVE SOUNDS (Masha Tupitsyn, 2014) from Spectacle Theater on Vimeo.

Audible Range: You’ve said that Love Sounds is the most “personal” thing you’ve made. What do you mean by this?

Masha Tupitsyn: Love Sounds is the last work in an immaterial trilogy, so on that level it is a return — as all trilogies are — to a question. And whenever you pursue a question for an extended period of time, it means that you are preoccupied with something. Something that you can’t let go of and that doesn’t let go of you. My preoccupation with the subject of love and the problem of language, gender, and mourning in relation to love is extremely personal. It’s my ear at work. So while I am using and arranging found material that is available to anyone and traffics through everyone, what I listen to — or more precisely, how I listened to it — and how I choose to orient myself through what I am hearing is highly subjective. I think critical inquiries can be far more personal and revealing than a so-called memoir. Regardless of however theoretically driven, a question still has a biographical origin that works through an individual.

AR: Love Sounds has played for audiences in cinemas and as an audio installation for museum-goers to explore at their leisure. Personally, I experienced it on my laptop computer. Did you have an ideal/authentic viewing experience in mind?

MT: I prefer durational experiences, of course, where the film plays out as a single, uninterrupted 24-hour event and where the viewers/listeners can spend lived hours with it. It is an experiential and cumulative work, so it needs time to unfold, time to speak. I’ve done a handful of durational screenings so far and it was an amazing experience each time. Living with the film gives it the kind of space and time it needs to be heard and felt. The weight of what cinema has said about love, and the discourse it constructed and contains as a cultural medium, cannot be underestimated or listened to superficially — in 20 minutes. It took time for that discourse to accumulate and it will take time to listen to and think about all of its different iterations. Also, each section is constructed as a long essay with many subsections, which you can only hear and identify gradually.

AR: Is the 24-hour duration arbitrary, or is the “day” an important marker for you?

MT: Both the structure of the film and love itself require endurance, so a single day is a template for that commitment. I’m interested in affective chronology, not simply temporal chronology. You can’t pass the time or be on autopilot with affective time. Nor can you bypass a major question by whittling it down into a soundbite. LS works on two levels: recognizing the dialogue we’ve all heard in cinema and in our own lives, and the enormous time it takes to listen to the language of cinema in this particular durational format. The combination forces us to encounter—rehear—the spoken canon of love as if for the first time. With new ears.

LS had to be made now for three reasons: Cinema as we know it is finished, the 20th century is over, and social contracts have been dissolved. This means that before we can construct new love stories in new forms and reclaim love for the 21st century, we need to first go back and review, mourn, and think through the oral narratives cinema has produced. Love is another example of something we no longer know how to describe, a situation we no longer know how to be in. Nothing lasts anymore, let alone two people together. Without a model and ethic of commitment we simply don’t have the time, patience, or endurance for the commitment that love takes. So we’re left with episodic, truncated encounters that fail to gain momentum and often don’t go anywhere. That’s part of why LS takes both a fragmented and durational form. LS is a new form for an old question.

Listening is the way through questions about love.

AR: How laborious was your editorial process? Where did you begin?

MT: I approached the work methodically in stages. The main concern before I could even begin was to figure out how to organize time. Once I figured out that I would assemble the film into emotional categories, and that each section would cycle through all the decades — 85 years — at once, then everything fell into place for me. Yes, I had an enormous amount of work to do (I didn’t even know how to edit when I started; I had to teach myself), but I knew how I was going to do it and that it just required stamina and dedication.

I made a rudimentary list of films to sample for every decade, which evolved over time — lists I could only compile because of the foundational work I had already done with the earlier books in the trilogy — mainly LACONIA: 1,200 Tweets on Film. I started with the 1930s, when movies really began to talk, and worked my way through every decade, ripping hundreds of MP3 clips (around 3500 in total) and filing them into folders. The ’70s and ’80s is my specialty, and therefore really fun to do. I did that for about 8 or 9 months every day. Sometimes that work felt endless and overwhelming because each clip required tailoring, fixing (sometimes the sound was bad), cutting, and labeling once I recorded it. Not to mention that this was just the technical portion of making the film. This wasn’t even the editing.

There were only a few moments where I felt I had taken on too much and asked myself if I would do it again. But those moments were usually when a problem presented itself, making the work feel endless. Those doubts didn’t last long, though. I was absolutely driven to do the work. Going back to your first question, LS was the culmination of all my interests, struggles, and abilities, so it felt like a total gift to do it.

AR: Do you think of Love Sounds as a document of movie obsession? And is it an experience perhaps best meant for cinephiles, for whom movie-love and love-love are perhaps not mutually exclusive? For me, one of the pleasures of Love Sounds is properly identifying the provenance of the dialogue. But for others, most of the “characters” in your film will be unfamiliar.

MT: I think LS is about cinema, not cinephilia. A lot of people have said that they enjoy trying to identify the movies in LS, and recognition-identification is definitely a big part of the way cinephilia works. I am more interested in critical listening than I am in trivia, recall, or identification. The film does not work with repetition in the same way that Marclay’s Clock does, for example. I want the dialogue events in LS to feel familiar on the level of affect and cliché — the shared script we all know and participate in when it comes to love — but unfamiliar on the level of understanding. If the viewer is spending all their time trying to figure out which clip belongs to what film, or has the illusion that they know what they remember hearing, then they are not really encountering or critically listening to the content with new ears. Because LS is an epic that consists of speech fragments, we don’t need proper diegetic narratives to anchor them. The narrative at work in LS is a cultural one, a social one. We already have the lingua franca and structure of cinema itself.

AR: Why did you focus mostly on dialogue rather than, say, kissing or heavy breathing for your love sounds? Wouldn’t “love language” be just as accurate a title?

MT: In the 24-hour version, there are all kinds of sounds — chimes, bells, trains, galloping horses, cars, ice clinking in glasses, clocks ticking. There is an entire subsection dedicated just to crying in HEARTBREAK. There are also instances of panting, breathing — diegetic and non-diegetic music. It’s all an extension of articulation and failure to articulate. It’s also just the environment in which language takes place all the time, in all of our lives.

The title, Love Sounds, is a description, a taxonomy, and a verb. It’s something that is language and not-language. Something simply for our ears, first and foremost. In the beginning of movies, the face was the voice. Text was our sound and our image. LS is also film that approaches love as an event of cinematic language. So the [section] titles confront language and how it cannot properly convey or hold the empirical, the affective. The titles are both exact and completely obstinate. They tell us nothing, but their signifying is very powerful.

What we need to understand about love is much deeper than its linguistic tropes or outlines. We think we have the words and know the definitions — that we’ve heard it all before — but we don’t. We know that when we start having to feel language: What people say hurts. There are huge gaps between feeling something and talking about what we feel. We often betray our experiences with language.

”…you, as a listener, without the aid of images, must sit in the existential and literal dark about love…”

AR: In the shorter edit of Love Sounds, you use Avital Ronell’s injunction to “…learn to read with your ears” as an epigraph for one section. Do you think that viewers (and lovers) are not properly attendant to aural/oral aspects of storytelling? The experimental filmmaker James Benning, for example, thinks that filmmakers moved too quickly to sounds, and haven’t yet learned to be properly attentive to the image.

MT: When it comes to love, movies have told us something that we can’t quite access in the same way in real life. And maybe don’t even want to. Benning is somewhat right. Filmmakers were too quick to sacrifice image for sound. Or one thing for another. But LS is asking for something else. It’s asking for us to listen to what we didn’t hear the image say. To what was communicated to us by and through a visual medium. Images trained our ears, not just our eyes. It gave us a set of beliefs and scripts — earworms — we still don’t know what to do with. For this reason, we need a listening viewer. Not simply a viewer or a listener.

AR: In what respect is your film a “history” of love in the movies? Since the film is carefully sorted and edited by subject, do you see Love Sounds as a kind of comprehensive (and comprehensible) archive?

MT: It is one version of an archive. It is as comprehensive as it can be given that it is a subjective orientation and pursuit — my choices, my cuts, my classification. So it consists of an enormous catalog of found material that is also necessarily constrained by language (English) and movie selection. The point was not to do every movie — it’s not possible, nor was it the goal. If every movie is included, where does the assessment and subjective interaction come in? How does the listening happen? Having said that, LS had to sample enough that patterns emerge and a sense of time is at stake.

What surprised me about making LS was how every movie has a love story in it, a love situation, or romantic dialogue. Whatever the genre, love is always part of it. Many things are done in the name of “love,” which is in itself part of the problem. For this reason, listening is required. That’s how I really found things. But if I had not already done all the other work in the trilogy first, I would not have been able to make LS on any reasonable timeline. I already had the education, as I said.

Second, each love story has multiple scenes about love, so how do you choose, where do you cut? The film’s eight sections were the organizing principle. But again, I realized that the categories were so porous and fluid, so what should they be, where should they be, and what distinguishes them? Not time — or time is only one aspect. Just because the sections and title progressions are interconnected doesn’t mean that TRUST-BETRAYAL should be confused with LOVE (there is a reason LOVE comes at the end of LS rather than the beginning), even though we’re constantly misrecognizing and mislabeling love. Cinema’s visual vocabulary — its seductive stars and familiar cues — are one reason for that. Like score, images force feeling. This means that you, as a listener, without the aid of images, must sit in the existential and literal dark about love in order to understand the continuum and the difference between something like love and betrayal, or between love in the 1930s and love in the 1970s. The categories are sort of affective tests and using only sound means you can’t get away with not listening and thinking. This is why some people quickly check out with LS. Listening is the way through questions about love.

For example, I might use a scene from Moonstruck and place it in FATE-TIME-MEMORY, but depending on where I cut the scene, I could use another part of that scene’s dialogue in SEX. Is that because it’s the same? No. It’s because we have to understand what the differences in the dialogue are, and the moment when the difference or shift occurs, in order to know why one conversation is in one place and another seemingly similar conversation is in another.

Love is not a metalanguage. Everyone has to encounter it for themselves. That’s what so risky and vital about it.

AR: Why was it important for Love Sounds to be a visual experience, and not, say, a podcast or audiobook?

MT: LS is a film made out of cinema. That is the source and the medium. Because LS is both a project about cinema and a project that says goodbye to cinema, it needs to be anchored in cinema — in its history and in its form — even as it leaves it behind with the digital and the post-cinematic. LS bookends the beginning of cinema, which was silent and only contained inter-titles, and the end of cinema, which LS reimagines as a kind of blackout. An absence. The black screen that you see in the film never produces a visual scene, but it does produce an image around the absence of an image. So the history of cinema is there, but it’s repurposed into a different format that requires reviewing.

AR: Do you see Love Sounds as being in conversation with other audio-intensive films? The only similar project that comes to mind is Derek Jarman’s Blue, which I know you’ve cited, but there must be others.

MT: I am interested in audio-intensive films as an approach, but I am more interested in the story of dialogue — in how people talk about love. In the actual content of sound. Talking and speech have always been the main cinematic narrative for me, and a running subject in all my work. So words are the central characters in LS.

I was trained as a classical musician and I was always obsessed with film scores. I grew up listening to soundtracks, even as a kid. From Out of Africa to Sex, Lies, and Videotape. So my ear is very keyed into sound and music. The other day I re-watched A History of Violence for a class I am teaching. I hadn’t watched the film in 10 years, but I knew immediately, without ever having checked before, that whoever did the soundtrack had also done the score for The Silence of The Lambs and Se7en. I haven’t seen Se7en since it came out. But I remember exactly how all three films sound much more than what actually happens in the films. It’s sound that connects all those movies, not just theme or plot. Or it is a certain tone that recurs as it addresses the question of male violence and the noir of veneer.

This is one way that LS works and why I was able to make it. The affective geography of music, that is, of listening to music, is inseparable from listening to the oral geographies that cinema has produced.