Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

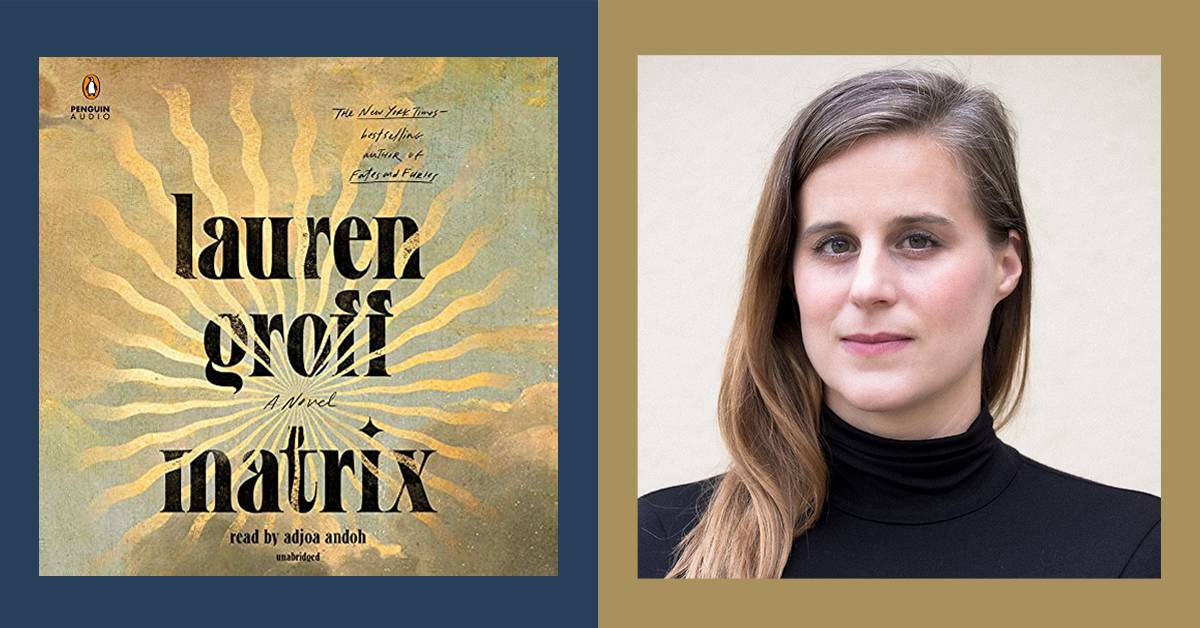

Tricia Ford: Hello, everyone. This is Tricia Ford, fiction editor here at Audible, and with me today is author Lauren Groff, who's here to talk about her latest novel, Matrix. Welcome, Lauren, and thank you so much for being here.

Lauren Groff: Thank you so much for having me on. I appreciate it.

TF: To give listeners a little background, Matrix is what I would call an inventive and daring example of historical fiction. It's set in the 12th century, in a nunnery, and it focuses on the life, loves, and power struggles faced by Marie de France, who's a real-life woman who was considered the first to write poetry in France, and someone that we know very little about otherwise. I'm very excited and feel very fortunate to have Lauren's imagination there to fill in the gaps and give us a full life to live. So what made you pick Marie de France as your focus for this book?

LG: Way back in college, over 20 years ago, I had two tutorials with an amazing professor at Amherst College named Dr. Paul Rockwell, and they were so good. We did a lot of translations, and one of the texts that we translated was The Lais of Marie de France, the first published woman in the French language, even though she definitely lived in England. We don't know much about her. She's like a hole in the tapestry of history, moth-eaten somehow, because she wasn't considered interesting enough to report the elements of her life.

Some historians have an idea that she might have been the the daughter of Eleanor of Aquitaine from her first marriage to Louis VII. Some people say she almost certainly was an abbess in either Barking or Shaftesbury, which are two abbeys in England. And some people say she was almost certainly an illegitimate daughter of some kind of nobility. We don't know who. So, it's all very complicated.

But I love The Lais themselves. They’re so interesting. They're fantastical short stories in poetic form that have unicorns running through them and magical boats and fairies. For the past 20 years, I've just been kind of obsessed. I've tried to do my own translation of her Lais. There are really good ones out in the world. It wasn't necessary, but I finally found a way to talk about her and talk about the contemporary world at the same time.

TF: That was awesome. Now your last full-length novel, Fates and Furies, was a very contemporary setting. So this is a real shift. Was that intentional? Did you feel a need to dive into another time period as an escape, or was it a way of somehow dealing with contemporary life in a different way?

LG: It was definitely not an escape. When I start a project, I do have an oppositional nature. It's really frustrating to be married to me. I wanted to destroy the thing that I've done before. I almost want to sort of push against that. I never want to be the writer who writes the same book over and over again. Some of my favorites do that; it's just that I don't want to do it myself. I wanted to challenge myself, but I was in a pretty big funk from 2016 to 2020. It was a pretty intense time to particularly be a woman in America.

I get very, very stressed, and I didn't feel as though I at the time was capable of writing about the contemporary world with the kind of moral rigor that I want to be able to, just because I couldn't understand everything that was coming at me in such unceasing, unrelenting ways. I couldn't see clearly enough to write, but I could tell a story slant, as Emily Dickinson puts it.

"I never want to be the writer who writes the same book over and over again."

I could find the story from history and make it so that today and the 12th century were talking back and forth across the ages. There's this amazing Ali Smith quote that I'm going to give you, if that's all right with you.

TF: Yes.

LG: “The shaft opens. The past and present exist in the same moment, and we know, as beings, that we are connected." And that's what I wanted to do with this. I wanted to trace the roots of how we got to where we are in the 12th century at a time when there were these upwellings over and over again, sort of like mushrooms pushing up from underneath the ground of a crusade. There were so many crusades happening all this time and it was basically the nascence of a very Western English-based imperialism. I was really interested in that, and I was trying to find the parallels the way that time and our time now were speaking.

TF: And with those parallels, what would you surface as the most profound? What did you find from 12th century that stands true to this day the most?

LG: There are a number of things that I think stand true today. Marie in this book is a person who sort of slowly understands the power she's been given by becoming a prioress at the abbey and then abbess and then begins to understand the uses of power. She does a lot of subversive things. But also at the same time she has internalized hierarchy and she has internalized a lot of the structures that even she is pushing against, and she uses them as weapons against other people. And so I think something that exists back then and exists today is that none of us are exempt from the influences of the larger structural systemic pressures that we are under at every single given moment.

TF: Very interesting. One thing off the top of the book, you dedicate it to “all my sisters.” And that reminds me, along with Marie de France, there's an entire community of women. It's pretty much all women. Can you talk about any of your characters, whether or not they were based on real women or perhaps women you know today translated into these historical characters, and do you have a favorite?

LG: So yes, this book is dedicated to all my sisters, and by that I mean in a spiritual way. But also I actually have a sister of blood and my husband has two sisters, and I love them very deeply also. This does not mean it's not for men also. I hope that men still read it. The characters in this book come from my idea of who they were historically, so there are real-life people here. There's Eleanor of Aquitaine, who is possibly my absolute favorite human in history, period. She was this extraordinary queen who first was actually just born a powerhouse. I mean, Aquitaine at the time was basically the center of culture and she was born extraordinarily wealthy, and so when it came time for her to make her first marriage, she married Louis VII, the king of the French.

She had some children with him, but eventually she didn't like him. He was very ecclesiastical. She got an annulment, left the channel, and became queen of the English. I think that she's just an extraordinary person. As the queen of the English she did a lot. You can see her pulling a lot of the reins from behind the scenes. Her second husband, Henry II, didn't like her very much. They had a lot of children, and then eventually she started whipping her male children up to such a point that they started to threaten their father's reign. She's this incredibly powerful, warlike, proud, beautiful woman who loves stories and storytelling.

"None of us are exempt from the influences of the larger structural systemic pressures that we are under at every single given moment."

She had three children become kings of England, one after the other. There was Henry, the young king, and Richard and then John. And another warlike queen that I really loved, too, was Queen Matilda, who was the daughter of Henry I and sort of got booted from her role, even though she was at one point the empress of the Holy Roman Empire. She tried to come back to the throne of England. Her cousin took it, and instead she fought for decades in order to reinstate her line and eventually Henry II came in. So, there are numbers of actual historical figures in there. There are a lot of nonhistorical figures, the nuns who populate that abbey as well. And I definitely pulled from the people that I love around me. I mean, I definitely put my mother into one of them.

TF: I had that feeling. I had to ask, because these women are just too real and too quirky. I mean, they could just be born of your imagination, but I had a sinking feeling that they were inspired by some real people. I really liked how no one was simple. Everyone was complicated and slightly unlikable.

LG: We can talk about that, because I find it hilarious that something that people say a lot when it comes to the contemporary literature is that it's not relatable. Why do we look to relate, right? Why are we looking to see ourselves reflected more beautifully in a mirror? Is the function of literature to reinstate the lazy biases we have about our own selves, or to sort of trick us a little bit and make us think of new things and change our minds a little bit. I would say the latter. Obviously “it's so relatable” is not actually a compliment to me. “Slightly unlikable” is great because I don't know a human being on this planet who at times is not slightly unlikable.

TF: When I say relatable, I think it's in the context of the story being so old. What do we have in common with anyone from the 12th century? And here are these characters that are feeling things that we do in a very similar way, like the amount of snark. Historical fiction and snark don't commonly go together, and there's plenty of snark among these women and these characters, which I loved.

LG: Oh, thank you. It's funny because I think our conception of the Middle Ages comes out of a lot of the work that was being made at the time, which is being made by clerics, right? People who take religion very, very seriously. So I think our vision is that everything was very solemn. There was no joy, there was a lot of death. But humans are humans in whatever century we live. They're wild and strange and incredibly funny.

TF: That's amazing. And the humor is unexpected because the setting is so downtrodden in so many ways. Listeners might be coming as historical fiction fans, and many might be coming that avoid it because they think it's too dry or too informative and not entertaining, and I have to say, there's none of that here. It's very entertaining. And I think the education part is more about the characters than it is about learning historical facts.

LG: Yeah. The book that I was thinking of a lot when I was writing this one was The Blue Flower by Penelope Fitzgerald, which is such an amazing book. But she talks about the life of Novalis, the writer and philosopher, and she does it with such a lightness that, even though it's a historical fiction, she doesn't have these long expository passages. It's almost like water that the characters are swimming through. It's not pretentious in any way. That was my model.

TF: I liked that a lot. Another, I dare say, theme that comes up here is you seem to be drawn to insulated communities. It's something you explored in Arcadia, which was set in a hippie commune. And here we are way back into 12th century at this nunnery. I was curious about what draws you to this, and I was also curious if there was any COVID or lockdown part of that. Was that intentional?

LG: I finished the draft of this book that my agent and editor saw in January 2020, so there was not an intentional line to lockdown. The publishing schedule, as a lot of people know, is weird and it's so long. It takes 18 months to get a book out into the world. So I was editing through lockdown, and thank goodness, because I got to spend hours a day with my nuns, who I love very much.

The life of a writer is fairly depopulated. I have my family, and some weeks they're the only humans I see, other than the postman; I ambushed him every single day. I was like, "Hey, want a coffee? How about a cookie?"

It gets lonely, and so being among this community was really, really helpful. I think you're right. Something that occurs over and over again is community in my work. Part of it is because I come from an incredibly tiny town called Cooperstown, New York, which is where the Hall of Fame is, the Baseball Hall of Fame, and which is where Glimmerglass Festival is. It's an incredibly beautiful, almost perfect looking town. But being raised in a place with one traffic light, zero movie theaters, in the winter, it's very, very isolated. There are no tourists. It's a lesson for a novelist, right? Because you start to see the personalities of every other human in town kind of exacerbated.

You start to see the way that one person's action affects a whole community of other people. For instance, I can remember divorces happening when I was a child and watching the fallout. And it's not just the fallout in the families that were involved, but also the friends of the kids and the families. So you start to see the ripple effects of a single action.

Writing novels is creating your own microcosm of the larger world inherently already. So it doesn't feel distant to me to do that intentionally. Any novel is a small enclosed a space with particular characters.

TF: That was interesting. I loved the image of you having your nun friends as your companions during lockdown. And they're now the world's companion, so they get released and the world gets to hang out with them as well. So that's good.

This is such an atmospheric novel, and when it comes to audio, narrator is everything. So I have to ask you, how did you get Adjoa Andoh, otherwise, known as Lady Danbury of Bridgerton fame, to narrate your book?

LG: I know. She's amazing, isn't she? I never, ever listened to my audiobooks just because I started to have a panic attack. But her voice is so spectacular. She's so right, and she spins the scenes in the way that I intended them. Oh my God. She's so good. She's such a good audiobook narrator. So what happened was my incredible producer, Sarah Jaffe, came to me with a clip of three women, and I said I really want this to be a British woman of a certain age, and I want her to be very able to be wry and I want her to have a very deep voice. She gave me a couple, and as soon as I heard Adjoa Andoh's voice, I just thought, oh my goodness, this is the voice of my book. I am so happy that she agreed to do it. I'm just so glad. I feel lucky.

TF: Now speaking of audio, do you listen to audiobooks or podcasts? Do you have a listening side of your story consumption?

LG: I don't listen to podcasts. I just cannot get into them. It's a problem. But I run almost every single day, and I'm running for hours and I listen to audiobooks at two times speed every single time I go for a run. I listen to them all the time when I'm cooking, when I'm cleaning the house, when I'm doing yardwork—I probably listen to 15 hours of audiobooks every week, which translates to three or four books every week.

TF: Wow. Do you have a favorite or current favorite?

LG: The one that struck me with a lot of force was The Country Girls [trilogy] by Edna O'Brien. She's an incredible, brilliant Irish writer, and I read these in physical form as well. But I think with audiobooks, something different happens. I think the voice of the narrator is describing space in a different way or else one's brain responds to the story in a different way without your internal voice happening. One day I was running and I was listening to this book and I started seeing the structure of the book in a way that I'd never, ever seen before without listening to it.

"I began as a poet. All I want to do is spend time with the actual words."

I think it's really interesting. It's just as much reading as reading a physical paper book. It just plays with a different part of your brain and sometimes a more vivid part of your brain. I cannot tell you how many times I've been on a run here in Gainesville, and I've been like, well, I really love this book. I should just go for two more miles. And so you end up finishing the book and taking the long way back. It's really fun.

This is the other thing too: I was doing a cross-country drive and I listened to Huckleberry Finn and I was blown away. It was so incredible. My kids were transfixed for the whole time. It's an amazing thing. It makes you see a text that you think you know in a totally different way. And so I would also recommend doing both and especially with books that you actually really know very deeply.

TF: Totally agree. My last question is, what can we expect from you next? What are you working on? I'm very intrigued because how you said you don't like to repeat things.

LG: Yes. I was already working on a book when Matrix came to me, and I had finished the first of a few drafts by this point, and I put it aside to write Matrix and I came back to it. I think it's going to come out in 2023, knock on wood. It's also a historical fiction. It's about 1609 in Jamestown, and it's sort of like a female Robinson Crusoe in some ways, but it's also playing captivity narratives of the 17th, 18th century.

I had so much fun going into Elizabethan language and rhythms. I began as a poet. All I want to do is spend time with the actual words. I love going back to Shakespeare and finding the vivid language, the vivid images that I wanted to use. So knock on wood.

TF: I'll be looking forward to it. Getting back to Matrix, what was your favorite part about writing Matrix? Was it the research? Or was it something else?

LG: The way that I work is through a lot of handwritten drafts, which I then jettison, then start over again, jettison, start over again. You have to mitigate the frustration. But finally, when I allow myself to sit down with the draft and I feel like it's becoming final, that's the time I love the most because I have the story, I have the characters. But paying attention to the way that the sentence is a fractal of the whole, paying attention to the way that the sound of the lines has to correspond with what's happening within the scenes. The actual, almost carnal, feeling of the language. All of these things become my favorite thing and the time when I feel the most joy.

TF: Matrix is amazing. I highly recommend it. Thanks to everyone for listening. And thank you, Lauren, for joining me today.

LG: Oh, thank you. It was so fun. I appreciate it.

TF: You can purchase, download, and listen to Matrix right now on Audible.com.