Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

Sean Tulien: Hi, I'm Audible editor Sean Tulien and today I have the great pleasure of interviewing Laura Ruby, a writer hero of mine.

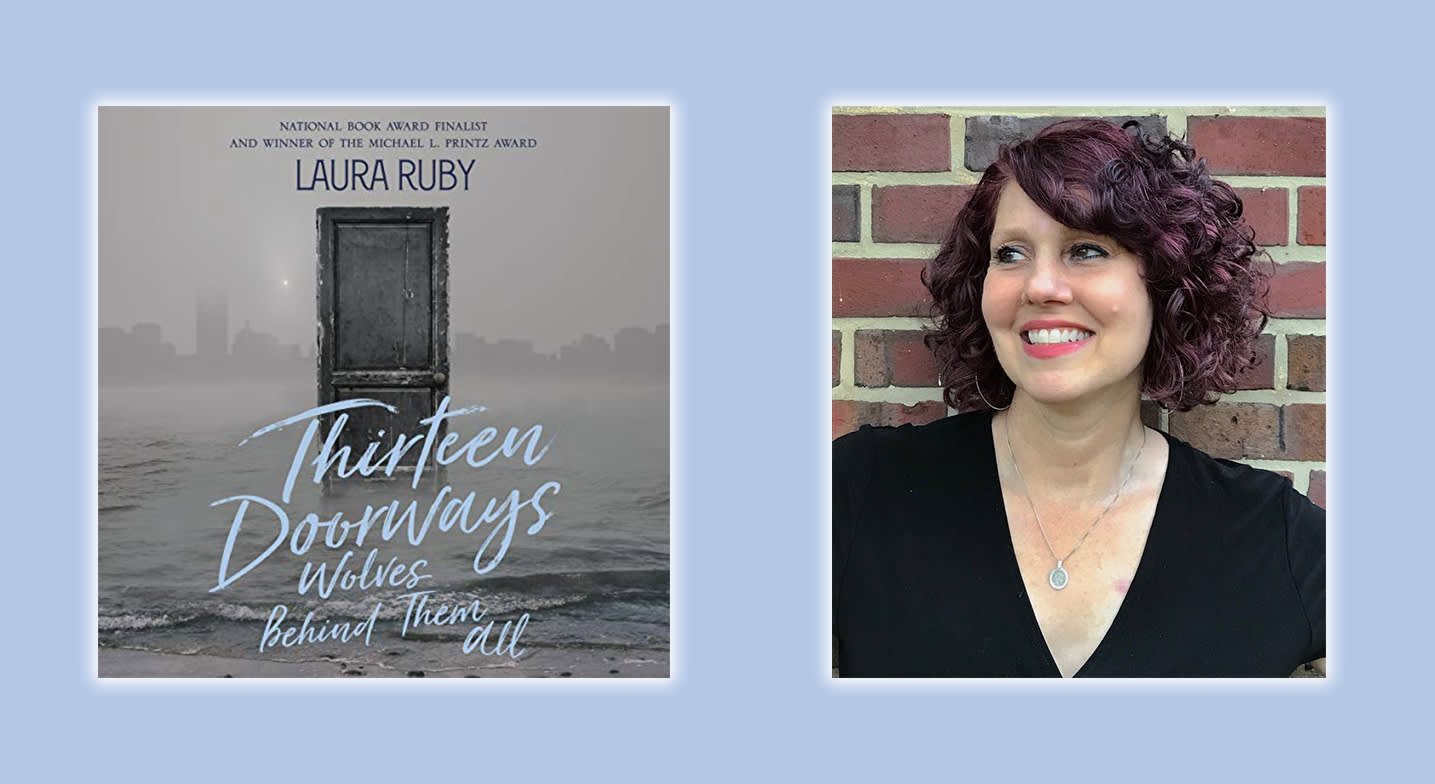

She's the author of the Printz Medal-winning YA novel Bone Gap, the Edgar-nominated middle grade novel Lily's Ghost, and several other acclaimed works for kids and young adults. Her new YA novel, 13 Doorways, Wolves Behind Them All, just got long-listed for the National Book Award. Congrats and welcome, Laura.

Laura Ruby: Thank you very much. I'm glad to be here, Sean.

ST: I'm really glad you're here too. So I've seen 13 Doorways, Wolves Behind Them All described by School Library Journal as "a feminist historical ghost story" and by Kirkus as "a layered, empathetic examination of the ghosts inside all girls' lives." How would you describe it?

LR: Oh wow. I've been calling it all of those things. I've called it a historical fantasy. I've called it a weird little fairy tale. I've called it a mystery. I think, like Bone Gap, I like to mix genres and I like to play with expectations of genre fiction. I like to blend them, and that's part of the reason why I like to write for teens and for kids. They don't have expectations of genre. They're willing to be surprised. They're willing to go with you so they don't care if you say, "Well, this is a mystery and historical and a fantasy and horror and ..." They say, "Cool." And they read. So I would say, for clarity's sake, that it's a mystery. It's a braided mystery of two girls. It's the story of two girls. One tells the story of the other and in telling that story, figures out her own story.

ST: I've got to say that the narrative device you use in this, I can't really recall seeing anywhere else. I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about that.

LR: Okay. It was interesting because I came to the narrative kind of late in the game. I started working on this book in 2002. A lifetime ago. Because it's loosely based on a real person: my mother-in-law, who grew up in a Chicago orphanage during the depression and World War II. When we were starting to talk about her life, which she never thought was that interesting. So she didn't understand why I was so curious about her life.

ST: I read in the author's note a line that really stuck with me, which was you were explaining to her why it's important and interesting and she said, "I'll be glad to answer all your questions"--while she was beating you at rummy. I was like, "That's such a good description." I feel like I can see her in my head, you know?

LR: Yes. Well, she was of a particular generation where the past was the past. Why dwell?

ST: Yeah.

LR: All she would say is like, "The food was really bad, Laura. The food was bad. Why talk about it?" But I was fascinated with it. And for a long time, because it was inspired by her, you know, I kept trying to capture her voice on the page, so from her perspective. So I tried it from first-person, from Frankie's point of view. And actually I was calling her Frances at the time, right? And I started to get muddled and it didn't work. It didn't work in first, it didn't work in third, it didn't work. And I realized, I'm telling the story of an institutionalized girl and institutionalized people, and so that means that your perspective is necessarily limited.

You don't really know what's going on in the larger world. I wanted to tell a larger story, and I realized that I needed somebody else to be able to give that perspective. I don't know. I always like ghosts. I mean, I return to ghosts. I've written about ghosts before. I'm fascinated with what haunts us--literally, as in ghosts, but also figuratively. And so when I came up with Pearl, I thought she would be able to describe a lot of what was going on outside of Frankie and Frankie's experience, and give us a bigger picture. I wanted her to operate as a first-person narrator, but also omniscient.

So that she would be able to dive into the heads and the hearts and the minds of everybody.

ST: As I was reading it, and especially as I was listening to it, it feels like there's this sense of a greater scope of these characters, but--full disclosure: Laura is a teacher at Hamline University's graduate program for creative writing for kids and young adults, and I was in that program. One of the things that you talked about a lot [in school] was psychic distance. I don't even know how I'd try to explain how the psychic distance works in this novel, but I know that it really works.

LR: Thank you.

ST: Because I felt invested in the characters as we're going, but also got enough information of the world around me to be able to paint a clear picture. But there's still space. How did you decide what to include and what not? Because I know that you're a big proponent of letting readers and listeners come to your stories and interpret them to a certain degree.

LR: First of all, I would want to say just for people who are listening, psychic distance--we were talking about this term and it might sound esoteric--and all it means is, basically, how close to the events of the story does the reader feel. Do you feel close, do you feel distant from events? Once I found Pearl and once I discovered her as a character, her curiosity about different things was what guided my choices. So she could choose to go into somebody's head or not. She could choose to explain somebody's life or not. And it just sort of depended on what she thought was interesting. And that has a technical term. What is it? Selective subjectivity, or something like that, if I wanted to be fancier.

But anyway, I just followed what she was curious about and that, to me, informed her character, but it also then informed Frankie's story. And for the most part, I didn't find myself cutting out a lot. I found myself adding more than taking stuff away, because I do think her little forays into the minds of, let's say, some side characters were really interesting and helped build the world of the story.

ST: Yes. The most interesting thing that I found was that she would observe something through her eyes that Frankie was experiencing, and then be able to go back in either a flashback or something she was revisiting from her perspective in her life before she was a ghost.

And I love that interplay; you can get that closeness and still understand the world really well.

LR: Thank you.

ST: You've already spoken about how your mother-in-law was the inspiration for this novel. I've read the author's note, and I encourage listeners and readers to do so as well because it's wonderful. It's very short, but very, very informative. I was wondering if you could go into a little bit more detail about the time that the story takes place and your inspiration in general.

LR: My mother-in-law was a really interesting woman and she was fascinating to me, very different from my family. I come from a background that's more like a Pearl, my narrator. Very proper and English and German and you say please and thank you, and on a birthday or at Christmas, everybody opens their presents one at a time, nobody eats dessert.

ST: That reflects my Midwestern sensibility.

LR: Yeah.

ST: Totally.

LR: So I have that background and then I married into this Polish-Sicilian clan, and everything is loud and raucous and a party all the time. And she was quiet, because she, I think, by her nature [was] shy, but she loved to laugh and she loved a good game. She loved to play games. And I remember one of our first meetings, and it was a dinner and she had made spaghetti and meatballs as Sicilians are wont to do. And I don't even know what topic we were on. She just mentioned, kind of out of the blue, "When I was in the orphanage and the nuns weren't looking, we used to sneak into the kitchen and grab an egg and suck out the contents or we'd scoop out a handful of Jell-O."

ST: Oh wow. And she didn't think that that was exceptional in any way?

LR: No, it was like she just offered it and then, I was like, "Wait, what? Wait, wait, help. Tell me more." And she'd just say, "Oh, you want another meatball?" And kind of move on. Because it wasn't remarkable to her. That's just how she grew up. And I thought it was so fascinating. But I realized too, in asking her questions that she had so little interest in telling the story that she did not think was important, that I had to learn how to communicate with her better in her way, which was by playing cards.

I was not a card player. So I'm like, "Okay. I've got to learn this game." This is what I need to do. And so she taught me how to play cards. I'm not bad. I got good enough that I could beat her at the end. But it took me maybe a decade because she's really good.

ST: So you were off and on, of course, it's obviously ... It's not a constant thing. But you were talking to her about her experiences for a long time.

LR: Oh, this was so many years, because I got her story in bits and pieces, out of order, which is actually how I think memory works. We like to tidy things up. We like to imagine that time operates in sort of a very particular way. It moves forward and it's Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and this is how it works. Well, first of all, I don't think that's how it works, but it definitely doesn't work that way for me.

People have made comments about a lot of my books in that I kind of hack up time. I'm really not paying that much attention to the way time operates or operates in a different way in my books because, for me, I'm living in the present, but I'm also remembering things I did before and anticipating at the same time. I'm kind of everywhere, and her story came out like that. Where she would tell me a little bit of about what happened when she was three and then she would mention something that happened when she was 17 and then she would go ... And so I was just taking these little gifts that she gave me and assembling them. And she had a very particular point of view.

So as much research as I did, and I did a lot of research--I went so far as to listen to recordings of people, women particularly, who worked in the meat packing districts of Chicago during the '30s and '40s just to get the cadence of the language down. I read tons of books on orphanages and memoirs by people who've lived in orphanages. All kinds of research. But she was really my primary source.

ST: And also the impetus to go into the whole project.

LR: Yeah, exactly. And the more that we talked, the more I just thought, her story has everything that I love. Everything that inspires me as a fiction writer. It had really screwed up family dynamics, really complicated, complex family dynamics. It had romantic and ferocious girls and it had wayward boys and it had a wicked stepmother. It had mad kings. It had, you know, girls locked up in proverbial towers, and I felt I really need to put this down.

ST: You're blowing my mind because, as I was listening to it, I'm like, "Oh my gosh, yes... Oh, that makes total sense."

LR: Yeah.

ST: I think that lends some thematic consistency because it's just like riding a wave, reading it especially.

LR: Well, that's what I tried to do when I was writing it and which [is] really why, I think, it took me so long to find it. Because I started this as straight up historical fiction, and I am not a straight up historical fiction writer.

That's really not my forte. It didn't feel natural to me. I felt confined by it. And sometimes when you put limits on yourself, it really works, and sometimes it doesn't. And it didn't really work for me. In finding Pearl, my narrator, and then following her interests and the things that she liked is where I also found why I was interested in writing about Fran in the first place--which sometimes is a mystery even to the writer. People ask all the time what inspired you, and you mention all sorts of things, but that's not really it.

ST: Yeah.

LR: I mean, I can say it's like, "Well, because she lived in an orphanage and that was really cool." Or blah or whatever. But it's really because the orphanage, though it was [a] difficult place to grow up, it was also a safe place, in many ways, for her. It shielded her from a lot of things. And the most painful things were the betrayals from the people who were supposed to love her.

ST: Oh yeah. Yeah, that makes sense. At least there's that bedrock of consistency. You know, even though the experience is not great at all, it's consistent.

LR: Well, yeah. And it's expected in some ways, and sometimes there are some nice surprises. You can make wonderful friends, there are loving concerned people that you meet there, and there were in Fran's life. It's just that it was her family that was disappointing--also not unusual for the time.

ST: I should explain that for our listeners. What Laura is talking about here is that her father, after losing their mother, and I won't go into detail about that at all because I don't want to ruin anything. But the father did, as a lot of people at the time did, according to your author note, put his kids, all three kids, into an orphanage and then visited them on Sundays.

LR: Yes. And we actually have all the records of his visitation.

ST: Oh, wow.

LR: My husband wrote to the archdiocese and got all of the records from her stay at the orphanage, her life at the orphanage. So we have her grades, and we have all these visitation logs. We can see that he was coming every visiting Sunday for years, and then suddenly, he wasn't.

ST: Yeah. First of all, I've got to applaud you for not getting bogged into the minutiae because you clearly had a lot of information to derive inspiration from, but do you think that might be why it started out as more of a straight historical fiction piece, because you had all that information?

LR: Yes.

ST: Where did the magical element come in?

LR: I was working on this book kind of on and off for ... at least, a decade, and trying to assemble those pieces. Writing really vivid historical fiction, I mean, it's a different ... You have to make observations about the time period that you're writing about that people haven't made before. You have to bring something to it that makes some sense. And a lot of times, you're really doing it in the characters. In trying to nail the world, I wasn't really getting the characters so well. So I remember a friend of mine who is a historical fiction writer, Gretchen Moran Laskas, read an early draft of this book when it was straight up historical fiction, and really you could describe it like, "Oh my God, orphanages, they're bad." It was really not good at all. It was not subtle; it was not sophisticated. There was just ... Ugh. And so she read it and gave me wonderful comments and in the nicest possible way said to me, "Please don't show this to other people."

ST: Was she saying it missed the human element?

LR: Yeah. Basically, is that really the story you're telling that orphanages are not great places to grow up? Okay. What else? What else is in there? You have to dig a lot deeper than you are. But I was, like you were saying, kind of bogged down with the 1943 something.

ST: To be clear, I was saying it's clear that you weren't bogged down in the final product.

LR: Oh, yeah, but I started out sort of overwhelmed with this sheer amount of information about Frances specifically, but also about this time period, which is just incredible. There's an incredible amount of research and information and books that you could get lost for forever reading about the depression and World War II, and I lost years doing it. But in thinking about what really attracted me to Fran's story, like I mentioned before, that the idea of family disappointing you and even betraying you--that's why I wanted to write this book. That's why.

ST: And the relationship with your mother-in-law, I'm guessing, as well.

LR: Yeah. And for her, but also because it keyed into all of my fascinations.

ST: Right.

LR: And so then to sit back down and say, "Okay, yeah, I have all of this information. I have all of these dates, whatever. So what?" What I want to capture is that piece of it that does feel like a fairy tale, and specifically the story of many girls, her, but others, other girls who have been locked up in other ways. Maybe they were not at an orphanage, but they were trapped and still are trapped.

ST: I noticed that--by the way, one of my favorite characters is Sister Bert, who's one of the more benevolent nuns--but ... I'm blanking on the name of the, I guess you call her the antagonist, the very harsh nun. What was her name again?

LR: It's Sister George.

ST: Sister George. I noticed that she is kind of trapped as well.

LR: She is.

ST: And that doesn't justify her behavior, of course, but still she's very much stuck in this framework and she's just trying to get by. She's trying to be herself. Found that interesting. I found that with a lot of the characters myself in reading it.

LR: Well, I was thinking a lot about that and Sister George is a sort of an amalgam of a lot of different real people that my mother-in-law dealt with, but also [that] her brother and her sister dealt with. So a lot of things that Sister George did, quote unquote, were done by various nuns in their lives. I mean it's funny that the orphanage ... It's based on a real orphanage; I did change the name. The real orphanage in Chicago, Angel Guardians, was started, I think, in the 1800s by feminists nuns, and it ended up morphing later. And so not every nun that you dealt with was ...

ST: Was on the same mission.

LR: Yeah, I mean, people have different reasons for becoming nuns and some out of piety, but some maybe out of necessity. And you don't know.

ST: Yeah. Or family pressure or just that's what was in front of them.

LR: Yeah, right.

ST: Yeah, yeah. Well, anybody that's listening, needs to go and see the cover. And you should obviously listen to or read the book, but the cover just sucked me in right away, so much that I didn't even notice your name was on it when I first saw it. I was like, "Oh my gosh!" There's this floating wooden door. And it's this misty backdrop of the city of Chicago, in what I now know is in 1930s. At the time, I thought it might be modern day. And the title, like everything just screamed out to me. Did you get to be involved in the creation of that cover?

LR: I was, but it didn't come from me. I'm pretty flexible when it comes to how a story could be represented in art. So if somebody asks, "Do you have an idea?" I'm like, "Well, I have 9,000 ideas. Do I have the right idea? I don't know." This was the art department of Balzer + Bray that really worked on this, with input. So they would show me different things. And I think what they wanted to do was have something that felt both classic and modern at the same time. That said "maybe historical", that also said "maybe otherworldly".

ST: Yeah.

LR: But that could be of our time as well.

ST: Were you were really excited when you saw the cover?

LR: I wasn't sure. Because I have to say ... I loved the cover of Bone Gap so much, to the point where I have this bee tattooed on my arm.

ST: Oh, yeah. That's cool. That's fitting.

LR: And it was immediate and iconic. This book was so different, and I'd worked on it for so long that I didn't even know what ...

ST: Right. So it took some time to kind of digest it or whatever.

LR: Actually, I think it took some time to get it right. So once it was decided the door would be a good idea, they had to get the right door.

ST: Right.

LR: And so they had the same photographer, Shawn Freeman, who worked on this, who did the bee art, do the photography of the door.

ST: Oh, it's so great. Because when I saw this, my immediate thinking was like, "Okay, so I'm walking into an experience that's a combination of a very real world." Right?

LR: Yes.

ST: Because it's a very iconic city skyline, and then there's this aged, weather-beaten door, just kind of floating, right?

LR: Yeah.

ST: So it's like, I know I'm going to go somewhere, I know it's going to be grounded in reality, but it's going to have these fantastical elements ... Obviously, I got more than that, but that's exactly what I got when I listened to the story.

ST: So when you see a cover, I think a lot of artists, especially writers, are like this, it's this interpretation of your work and there's an initial skepticism. At least, there always is for me whenever I see anything I've worked on, even if it's just an illustration for an article. Do you feel that way about narrators as well? The first time you hear their voice telling your story?

LR: I do. And so, and sometimes it can be difficult because you have a sound in your head. A lot of my process, especially when I'm starting something fresh, is trying to find the sound of the book. There's a sound of characters, there's your own sound, but there's a sound of a book and it has to be there ... And I can't actually write until I know what the narrator sounds like. Like what does this narrative sound like?

ST: So you very much hear those characters in your head.

LR: I hear it in my head, and I do read out loud a lot. Because it has to sound right in my head, but it also has to sound right out loud. And that's almost two different things. Your eye and your brain do different stuff when you're just reading. Because you'll skip things if it doesn't compute, or if it's glitchy, your brain fixes it for you. But when you're reading out loud, and I listen to tons of books, I love audiobooks, but you cannot hide, right? So when you read out loud, you'll hear every repeated word, you'll hear every funky phrase, you'll hear everything cluttered or overdone or to the point where it's like, "Oh wow, this is ... Oh my God." So I often read stuff out loud and then just take notes and cut as I go. I have gone so far as to tape myself reading whole novels and listen back. I'll go running, listening to myself. It's weird. I'm not in love with my own speaking voice, so listening to myself is bizarre. But because I do that a lot and because the process of out loud and sound is important to me, it is difficult to hear other people reading my work. I get so used to the way that I've interpreted it. And clearly, this is a performance, and so, so, so, so when a professional reader reads your work, they're performing it.

ST: They're bringing something to the table.

LR: Yeah. A great reader does so much for a piece of work. They're acting and they're bringing their own emotional experiences and their own interpretation of certain lines. They're emphasizing different things.

ST: Yeah. We recently got the audio masters to listen to as well, and the narration's by Lisa Flanagan, who is a great fit for the book. The way she speaks the Italian lines is amazing. I'm convinced, at this point, she does speak Italian. The Irish accent she does is just phenomenal, right?

LR: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

ST: Slips in and out of it like it's a glove. She has a very matter-of-fact voice but also a lot of warmth. So it's incisive in the sense that I believe her, and I know that I trust her, but also there's some vulnerability there too. I love it. I think it's great.

LR: Wow, that sounds great. I'm really glad because I want that for the book. And I want that in an audiobook, that somebody brings all of their talent to bear and add to the experience, which is, again, why I listen to a lot of audiobooks, because I love hearing ... There are books that I have print versions, electronic versions, and audio versions of because I want them everywhere and I want them in every way.

ST: Right.

LR: I love story that much.

ST: Yeah, that makes sense. So the last thing I want to ask you is, what's next for you in your writing career? And obviously there's things you can't tell us, but anything you can?

LR: Well, I'm going to keep working on YA. So there will be definitely more YA novels. I have many projects in various states of completion, and I'm trying to figure out which one is going to be most interesting to me. And sometimes the world makes that decision for you. We don't live in a bubble, so all kinds of events are happening and swirling around us. And so, for example, Bone Gap, I could not have written Bone Gap now.

ST: Really? Why?

LR: Because that's a book I wrote, I think, to fall back in love with writing. And I think in a lot of ways it is about love. It's a feminist story, but I'm a lot angrier than that right now. The tone would be completely different. It would be different. It'd be a different book.

ST: There's a lot of tenderness in Bone Gap.

LR: Yeah. I think there's tenderness in 13 Doorways as well.

ST: I agree.

LR: I think it's a different kind of tenderness. And I think it's because I was affected not just by stuff that was happening in my life, but just the stuff that's happening around me. So that's going to guide what kind of projects I'm interested in. But I am always looking to try new things. I don't like to be stuck with any kind of genre. I want to write a thriller, if I can figure out how a timeline works. The way people expect it. I want to write that. I've been playing around with graphic novels.

ST: Oh, cool.

LR: Yeah. I think it's so fascinating. I am fascinated by the form. I did not grow up reading comic books, but I've read a lot more graphic novels in the last five, seven years, and I think they're amazing. So, so interesting. I can tell you this, I handed this book in, the manuscript for 13 Doorways, in 2017, I'm pretty sure it was either February or March; then just two months later, I was diagnosed with cancer. So I was sick for a certain amount of time. And one of the things that happens when you're on chemo that people don't really talk about ... Well, first they don't talk about how boring it is to be sick. It's very boring.

ST: Very boring.

LR: It is exceedingly boring to be ill. It's so boring. It's so boring. It's awful, scary, and boring.

ST: Is that because a lot of the time is spent in bed?

LR: Yeah. I mean, because you can't really do stuff. But for me--and I think that you probably would share this--I'm used to telling stories in my head all the time. There are stories in my head constantly. I'm constantly telling myself stories, I'm constantly listening for interesting little tidbits that people say and little glittery things that I could pick up and put into a piece of work. But my head was not working in words at all. There were no words. When I was on chemo, no words. They were gone. And that was really weird. But I saw lots of things. I was seeing pictures.

ST: Interesting.

LR: So I'm not sure if my brain was compensating or like, "Well, we can't think about [a] story this way, so we'll think about it this way." So I saw tons and tons of pictures.

ST: Interesting.

LR: So I thought, "Oh, well maybe, maybe, I could tell a story in visuals." So it got me playing around with graphic fiction. So I have ambitions to do some projects that way.

ST: I really hope you do. I think you'd do an amazing job as a visual writer. I think you'd be great for it. And if I could sell it a little bit more, the thing I like about writing comics is that it's so structured, right? Like you know generally the number of panels on a page and the spread count, and the page count specifically. It's freeing in that it's limiting. And I find that's a problem with me. Being creative without some sort of limitation is impossible.

LR: I consider that a really interesting challenge. I like the idea of trying to do that. And I love how point of view works in comics, and that it's like it's every point of view at once in one panel. You can have a line of narration, you can have dialogue, you can have ... I mean, it's amazing to me. So there's a lot of opportunities there. So that's a very long way of saying, I don't really know. I kind of want to write everything.

ST: Well, you've got options, clearly.

LR: I have a lot of options, so we'll just have to wait to see.

ST: Well, if you do go with the comic book sometime, just promise that you'll try to find a way to get it into audiobook format as well, because I've found that a lot of the best comics ended up being really good audiobooks too.

LR: Really?

ST: Yeah.

LR: Oh, that's exciting. Yeah.

ST: Yeah.

LR: Okay.

ST: Okay, great. So thank you so much for coming. I want to repeat this awesome news that 13 Doorways, Wolves Behind Them All just got long-listed for the National Book Award. I'm convinced that it's going to win. I think it deserves to win.

LR: Thanks.

ST: I wish you luck, and I'm really thankful you got to come here and talk with me.

LR: Thank you, Sean. It was great.