Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

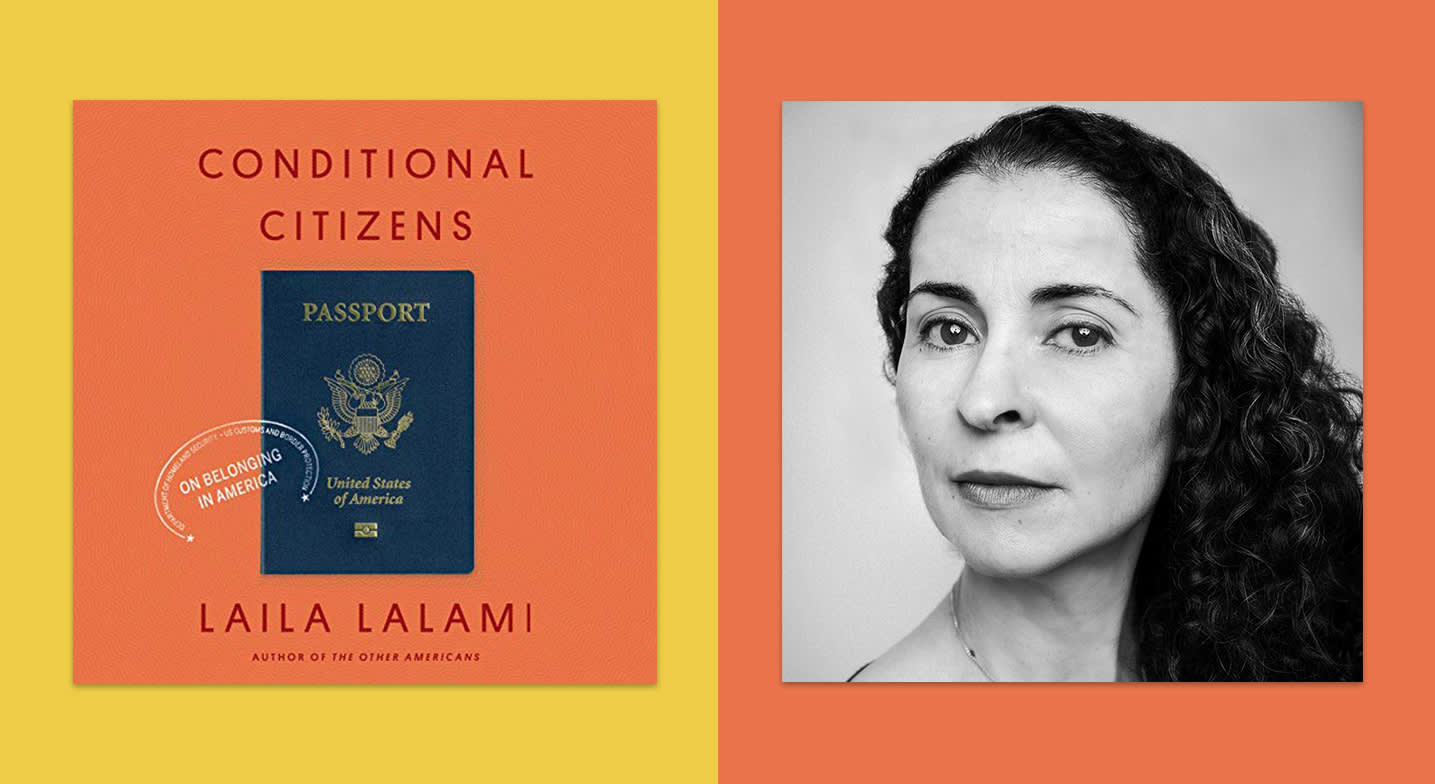

Rachel Smalter Hall: Hi, I'm Audible Editor Rachel Smalter Hall, and I'm joined by Laila Lalami to talk about her new essay collection, Conditional Citizens. Ms. Lalami is an award-winning novelist and university professor whose previous work includes The Moor's Account and The Other Americans. Laila, thank you for being here with me today.

Laila Lalami: Thank you so much for having me.

RSH: I'm really delighted by this new essay collection and especially the range of topics that you explore in Conditional Citizens. And just to give our listeners a little bit of an idea, one essay is about border walls, while another one describes an experience you went through as a young woman with workplace sexual harassment. And so, I'm curious to know how you would describe the collection as a whole.

LH: It is a collection of essays on the theme of citizenship, on the relationship between citizens within a country, and a relationship that each of us has with our government, the elected representatives, the people, the agents of the state, police officers, people who represent the state in our name. For example, the essay on sexual harassment, it's looking at the rights that we have to be free of harassment in our workplaces and how those rights actually play out in reality, like in practice. In that essay, I end up linking it to the case of Christine Blasey Ford, when she stood up and said, "This is what happened to me," and brought her case to the Senate Judiciary Committee and how that was handled. It really is a book that looks at our experiences of equality or inequality.

RSH: You're most well known for your work as a novelist, and so I'm wondering if you could share what inspired you to go this route to publish a collection of nonfiction essays about this idea of citizenship and equality.

LH: All of my previous work has dealt with themes of identity and belonging, almost all of my characters have crossed borders, whether they're tangible or intangible. In The Moor's Account, it's a story about an enslaved man from Morocco who's brought to Florida with the Spanish expedition in 1528 with the goal of claiming it for the Spanish Crown. Of course, everything goes wrong, and he's one of the survivors of that expedition, and he narrates all of that adventure. In The Other Americans, it's the story of a family where the parents immigrated from Morocco to California in search of safety because the father had gotten into some political trouble in Morocco and they were looking for safety. And of course, the book opens with this mysterious hit-and-run accident in which the father is killed, and then the family is brought together again and they have to... It's basically a story of grief and mystery, it's also a love story.

…This citizenship, this status that is supposed to make all of us the same…in moments of distress like this, you start to notice how, in fact, citizenship is really tied up with notions of race.

Throughout the writing of these books, I had been writing essays and criticism in different venues, oftentimes in The Nation but also in The New York Times Magazine, The Guardian, and other places. So, I've always written nonfiction, and I knew that there would come a moment where I might decide to sort of just put all of this writing in a book. And as it happened, while I was working on The Other Americans, the Democratic National Convention, the previous one from 2016, took place. This gentleman named Khzir Khan showed up onstage with his wife, Ghazala Kahn, and it was this really electrifying moment where he was advocating for Hillary Clinton, but he pulled out his pocket copy of the Constitution and basically was saying, addressing Trump and saying, "Have you even read the Constitution?" It was just very moving moment because his son had died in combat in Iraq.

What followed was that that family was attacked by surrogates of the Trump campaign in extremely Islamophobic ways. I ended up writing a column for The Nation about it, and it was called "Conditional Citizens." The idea is that that couple was American up until the moment they had criticized Donald Trump, and then suddenly all that ugliness came out. So they were citizens, but only if they were quiet and supportive of whatever their government was doing. It was from that moment that the idea of "conditional citizens" germinated in my mind, and I just started to think of all the other experiences that Muslims in America have, experiences that they share with other marginalized groups, and then I started writing essays on that theme of citizenship and inequalities. That's how the book came about.

RSH: Early on in the collection, you talk about what it was like to be an Arab Muslim in America right after 9/11. And so I was wondering, as a listener—that was almost 20 years ago—what is it about this moment that felt right to you for this collection? And so, I wonder what you think that collection might have looked like 20 years ago versus now, how have you changed as a writer, or how has our moment changed?

LH: Well, in some ways, it has changed tremendously and in other ways it hasn't. My interest in these issues really has only deepened. It hasn't changed, it has deepened, and some things in the United States have improved tangibly and others haven't. For example, we have marriage equality, but on the other hand, we have major attacks on voting rights, particularly for indigenous people, Black folks, and people of different national origins. And so, with every step forward, we also see steps back. I think the reason that I decided on this year to put out this book was because it was coming up on the 20th anniversary of my naturalization ceremony. I'm an immigrant from Morocco and I was naturalized in 2000. And as you know, that date, the 20-year anniversary approached, it really got me thinking about that moment in 2001 and how things have changed and how things haven't changed.

One of the really startling things for me is that obviously I couldn't have predicted that it would come out during the pandemic, but a lot of what is happening right now is really bringing up some of that sense of emergency after 9/11, and also some of that sense of distrust. For example, after 9/11, that distrust was directed at Muslims in America, who were basically treated as foreigners or as threats to national security. They were surveilled, particularly in New York, as I'm sure you know, by the NYPD. It was just the massive surveillance of Muslims. But what we're seeing now with the pandemic is that sense of distrust being turned against people of Asian descent, particularly Chinese people. And so, there's all kinds of ugliness now that's coming out with that.

Again, to me, that's a reminder that this thing that we take for granted, this citizenship, this status that is supposed to make all of us the same, that is supposed to protect all of us the same, at least according to the Constitution, ends up, very quickly, in moments of distress like this, you start to notice how, in fact, citizenship is really tied up with notions of race, and that comes up at moments like that. Because historically, the citizenship was tied to whiteness. And so when you have a moment like COVID, it shows us again, that that connotation still exists in people's mind, and so they feel they can say things like "go back to your country," or "this is your fault," or "we're in this position because of you," and none of that is true.

RSH: You bring up the naturalization ceremony, and I hadn't put that together, that it was coming up on 20 years, but I remember you saying in the book that it was the year before 9/11 that you were naturalized. I really adore that story that you opened with about celebrating with apple pie. There's just such a charming innocence about it in a way, and you really used that as a springboard to set up the rest of this collection. I was noticing how you use these personal stories to explore big political ideas, and I have to say some of the anecdotes are really stunning. And if you don't mind me sharing a few; you talked about the border agent who asked your husband at the airport how many camels he had to trade for you as a joke, or on September 11, the actual day, the coworker who asked you, who was over a deadline, if you were going to shoot him because isn't that how you people solve things?

As a novelist working in the medium of nonfiction, and I know that you you've done quite a bit of writing in that vein, but what was it like for you to pull so explicitly from your own life story for this collection?

LH: Somebody was asking me about this yesterday too, why bring up things that range from the microtraumatic to the openly traumatic in a book like this? Honestly, the only answer I can give is that I am trying to tell a story in the most truthful way that I can, and I can't tell this story of citizenship without also turning that appraising gaze both inward and outward. And if I turn it inward, then I have to share what it's like to be a person who is nonwhite, who also happens to be of the female persuasion and the Muslim persuasion and all that, and how that has impacted my interactions with agents of the state like border agents or police officers and so on. But then once I have shared that, then I try to use that to connect my experience with the experiences of others.

I am trying to tell a story in the most truthful way that I can, and I can't tell this story of citizenship without also turning that appraising gaze both inward and outward.

So, my goal in sharing it is really to use it as a way to connect to other people and to connect to the experiences of others, and in many cases, in fact in most cases, people who are far less fortunate. Because one of the things that I never lose track of in this book is, for example, I can talk about what it's like for me to be a Muslim woman in the United States, but at the same time, I don't wear a headscarf, I happen to be light-skinned. So, a lot of what I get exposed to is far less violent, frankly, than somebody who, for example, covers or is black. In the book, I use these experiences, but I also try to connect them to the experiences of others, if that makes sense.

RSH: I really enjoyed that element of the personal in the collection. And just between you and me, I very much enjoyed especially the anecdotes about your mother-in-law, the Cuban American bruja she called herself because her birthday was on Halloween. Those passages about her were really moving, and I just wanted to thank you for sharing those with us.

LH: Oh, it was really a joy to write about her. I do miss her so much.

RSH: Another story you bring up that struck me is you talk about speaking at a literary gathering a number of years ago. The moment I want to talk about is this—you write about this redhead with fashionable glasses in the audience, and she spoke up and said that the only Muslim she ever saw on TV were terrorists or extremists, and then the question she posed to you was, "Why don't I hear from more people like you?" And you're standing there on the podium thinking, "You are hearing from me right now," but you talk about the awkward position that that put you in. And if I may, I'd like to [read this passage] from the book: "Having to explain this mismatch is not a task I chose for myself, but from the moment I moved to the United States, it was asked of me with disturbing regularity." Laila, I wonder if anything has changed since that day at the literary gathering, or if you often still find yourself as the only Muslim woman in the room who is asked to carry this burden of being asked to teach others?

LH: I have to say, well, first of all, we're in a pandemic, we're all in our homes, so I'm not doing in-person events. But whenever I do these events, I guess it depends on the space. In certain spaces that are more diverse, it doesn't come up as much, but in others, it does come up. I think that there is a kind of impulse and a kind of curiosity, and it just expresses itself when faced with someone like me, "Oh my God, oh, here's the Muslim lady. I can ask her this burning question that I've meant to ask for a long time." I feel very conflicted about it because on the one hand, I feel that there is plenty of information for people to educate themselves, and it really isn't that hard to open the newspaper and read what it says about the topics you're interested in. You don't have to confront an author who's there to talk about a historical novel about a group like ISIS, for example.

I think if we had a more diverse workforce in media, then we would have a higher quality of coverage for all the issues because we would be hearing a more complicated perspective on the news.

On the other hand, there's the educator part of me that finds it not shocking, but distressing. The educator part of me finds it distressing that with all of the information that there is out there in newspapers, in magazines, in books, that there is still that level of ignorance out there and that it expresses itself at these social events. And to me, that's almost an indictment of the media and the way in which it's actually informing the public. Clearly, information is not actually passing through to the public. I do feel a little bit divided about it.

RSH: Do you think any of that could change if there were more opportunities for Muslim women or Arab women in the United States, if there were more opportunities at the table?

LH: I mean, of course I think that when we look, for example, at media, the people who would run our newsrooms, the people who shape what the news looks like for us, who tell us what the important issues of the day are and what issues can be safely ignored, those newsrooms across the country tend to be mostly white and mostly male. I think if we had a more diverse workforce in media, then we would have a higher quality of coverage for all the issues because we would be hearing a more complicated perspective on the news.

RSH: Right. Of course. You mentioned this coming out in the middle of a pandemic, which must be a very different feeling as an author who's been published before, but I guess we're all going through this at the same time. I wanted to ask you a bit about the narration, and I was trying to put together whether the narration would have been completed before the pandemic or during the pandemic. Let me back up a little bit to just say it was a treat to hear you do your own narration. And from what I know of your other work, I believe this is your first time narrating.

LH: That's right.

RSH: What was that experience like? Was it during quarantine? Was it before quarantine? Tell me a little bit about that, if you don't mind.

LH: I was really excited that I would get to do the narration for this book. Previous books had been narrated by actors. And oftentimes, the process was to just choose between a couple of voices, but then since this was nonfiction and it was in the first person, it was my big debut. I was very excited. We started taping, I believe it was in February, so it was before the pandemic. Over the course of two or three days we taped it all at a studio here in Santa Monica. But then they called me up because there were a couple of places that needed pickups or what's called pickups, either there was noise or there was something that wasn't quite right. They had a few sentences that needed to be redone, and that had to be redone the week that we went into lockdown, and so they were like, "The studio has been disinfected. It's totally safe." Of course, I showed up with a mask and the gloves and I just did my few pickups, and then I got out of there.

RSH: Wow. And now it's here. I think with there being those personal stories woven in, it really does elevate it to hear it in your voice. I really enjoyed that quite a bit.

LH: Thank you.

RSH: Thank you again, Laila Lalami, for talking with me today. To everyone who's been listening, Conditional Citizens is available now in the Audible app and on audible.com.