Joe Hill was steeped in storytelling from a very early age, having grown up in the household of novelists Stephen and Tabitha King. He’s enjoyed a prolific, but thoughtful career so far, from his stunning debut Heart-Shaped Box, to NOS4A2, which the Times called “whopping, immersive.” His graphic novel Locke & Key was made into an Audie Award-winning book with Audible Studios last year. Audible’s Reid Armbruster talks to the author about his latest best-seller, The Fireman, and his relationship to story and voice.

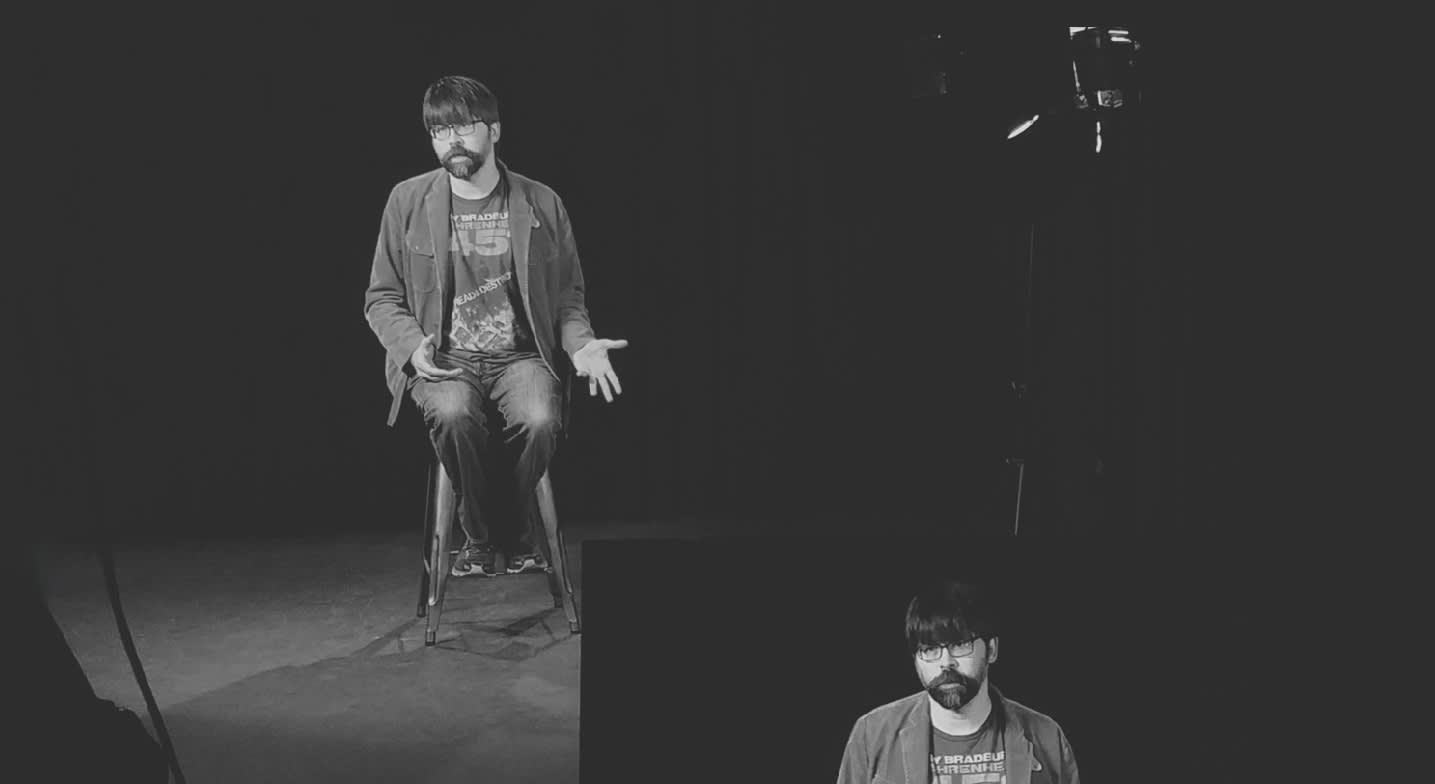

Audible: First of all, congratulations on The Fireman. I don’t think you could be wearing a more perfect T-shirt for the occasion: “Ray Bradbury Fahrenheit 451.”

Joe Hill: When Ray Bradbury started Fahrenheit 451, the original title was “The Fireman.” I believe it began as a short story and then eventually he expanded it up to a full-length novel, and in the process, changed the title. My feeling is Ray Bradbury’s leftovers are better than most of my ideas, and if Ray didn’t want that title, I’m glad to help myself. That’s how the book became The Fireman.

A: Could you tell us in your own words, what it’s about?

JH: The Fireman is a plague novel. It’s about this fungal infection called “Dragonscale” and there’s no cure for it. You get it on you and when you feel anxiety, when you feel panic, it begins to smoke, and if you can’t control your fear, you burst into flames, and die. Hospitals are burning down, neighborhoods are going up in smoke, the charred dead are on every street corner, and in the midst of this chaos, a young nurse named Harper comes up infected, and is also pregnant. If she can survive long enough, she’s likely to deliver her baby healthy. She resolves to survive, and that’s the story.

A: Without giving too much away, who is the Fireman?

JH: On the one hand, we have Harper who wants to live out this crisis, even though every day could be her last. To survive, Harper goes looking for an almost legendary figure called “The Fireman.” The Fireman is also carrying Dragonscale, but somehow he’s learned to master it.

A: I absolutely love that Mary Poppins plays a rather central role in an apocalyptic tale.

JH: Yeah. There is a lot of Mary Poppins stuff in Harper’s head. Harper is a tremendously decent, sunny, optimistic, good-humored woman, and as a kid, she just loved those Disney musicals of the ’50s and ’60s, and still kind of wishes the world was a place where you could celebrate great moments by breaking into synchronized song and dance.

A: Sticking with the apocalypse, could you say a little bit about this passage from The Fireman? “We really are living in the zombie apocalypse. It’s just that the zombies are us.”

JH: Yeah. You know, I’m a zombie apocalypse guy — and I think there’ve been some great stories on that subject. But I also think the stories feature a somewhat troubling theme: a small, elite band of the healthy, ruthlessly taking out the infected and the sick, and they have permission to do so because they’re zombies. You can’t have empathy for them, you can’t feel for them.

I did decide to write this story where you could look at it as the zombie apocalypse, only the zombies are carrying this stuff, Dragonscale, they still retain all their intellectual and emotional facilities, and the justification for taking them out is more clearly selfish. I thought that was worth examining, and I thought it was an interesting inversion of the sort of apocalypse story we all think we’ve gotten used to.

A: It seems like you’re raising very fundamental questions about what it really means to be sick.

JH: Well, I do think we’re living in an American moment when it seems very easy to stoke up people’s fears.

I have a deep mistrust of any sort of thinking which treats the other as less than human. “We have to fear these people because they don’t think like us, they don’t look like us, they don’t believe the things we believe, they’re somehow dangerous, and we need to protect ourselves” instead of trying to practice some sort of basic empathy.

A: No spoilers, but does humanity have the capacity to truly adapt and evolve to these kind of situations?

JH: I’ve never quite bought these stories where all of humanity is in a state of crisis, and suddenly, we revert to an animalistic brutality, and we’re ready to bite each others throats out for the last can of beans. If that is who we are in a pinch, you almost have to say, “Is humanity worth saving?”

I don’t think that that is who we are, though. I think individuals, even when faced with the worst, still find something to sing about, still find something to laugh about, still care for one another, still sacrifice for one another, and it’s these small, quiet decisions to perform small, little decent acts — that fascinates me and that I find hopeful.

A: Switching gears completely: tons of pop culture references in The Fireman.

JH: Everything I’ve ever written has been some kind of reaction to the stuff that turns me on. My first novel, Heart-Shaped Box, was about a man who buys a ghost on the internet. He buys it as a joke, but then finds himself running from it. In my mind, Judas Coin was always Kurt Russell, frozen at about 48, with the big bushy beard he had in The Thing.

My second novel, Horns, I was thinking a lot about Kafka, and The Metamorphosis, and I wanted to write something that explored what it means to be changed into something that people find horrifying. When I wrote my third novel, NOS4A2 (Nosferatu), I wanted to play with some of the ideas from It, by Stephen King. That’s a book that I read over and over again.

A: I’ve heard of It (laughs).

JH: Yeah. Terrific novelist. I think he’s got a real future. The Fireman is no different. In some ways, it reflects upon the great end-of-the-world novels of the ’80s, In other ways, it’s very much a fun-house-mirror reflection of the Harry Potter novels. I don’t know if anyone will see that but me, but I definitely see the same narrative scaffolding that works so well for J. K. Rowling, right there under the surface of The Fireman. I’m a big British invasion guy.

A: I was just about to ask you about the Rolling Stones.

JH: I’ve managed to work my Stones/Beatles obsession into every single book so far, maybe more in The Fireman than any other place.

A: “Desert Island” question: You can bring your Beatles collection or your Rolling Stones collection. Which one would you take?

JH: I mean, I’d have to pick the Beatles, especially if I could take the solo albums, as well, Lennon’s solo albums, Harrison’s “All Things Must Pass.” This is probably getting a little “inside baseball,” but ‘68 to ‘74 was the golden period of the Stones, and that’s just not a match for the body of work that the Beatles put together.

A: Speaking of listening to things, as you know at Audible, we’re all about harnessing the power of voice specifically. We were really struck by a passage in The Fireman that describes the character, Nick, who’s deaf: “When you had no voice, you had no identity.” Can you expand on that a little bit?

JH: Harper winds up going to a place of shelter called “Camp Windom,” and Camp Windom is a secret community of the ill. Well, as things start to go bad in Camp Windom, a punishment becomes popular: People who violate even very trivial rules have to carry a stone in their mouths as a form of punishment. When you have a stone or a rock in your mouth, you have been literally gagged, shut up. In that way, Nick, who was deaf but also mute, is running ahead of the group.

He is already a non-person, people don’t notice him anymore than they notice their own shadow because he has no voice. In the end, it turns out that, in fact, Nick has quite a strong identity. It’s not his fault that other people have failed to recognize it.

A: You hinted at this earlier, but you come from a family of very talented storytellers.

JH: It’s true. I write as Joe Hill, and I started writing as Joe Hill when I was 18, because I was trying to keep secret the fact that my mother is the great novelist Tabitha King who’s put together a huge body of work, and because my dad is Stephen King.

I always wanted to make stuff up for a living. By the time I was 12, I was writing every day, so it was always something I tremendously loved. I knew I wanted to write, but I was afraid that I might do mediocre work that would get published anyway because a publisher saw a chance to make a quick buck on the last name.

I remember my big breakthrough was I sold an 11-page Spiderman story to Marvel Comics. I thought, “Oh, my God. I’ve finally made it.” Eventually, I sold a book of short stories, 20th Century Ghost, to a small press in England. Not long after that, it came out about my identity and who my parents were, but by then, I had learned some things I needed to learn and I had found my way to a voice that seemed to be uniquely my own.

A: Let’s get into audio for a second.

JH: Sure.

A: Kate Mulgrew was a brilliant choice to do the performance. Did you have anything to do with her selection?

JH: Yes. I first came across her work when she happened to read a short story of mine, “By the Silver Water of Lake Champlain,” for a collection called Shadow Show that was honoring Ray Bradbury. I just loved her performance — she just made me sound so much better than I really am. Then she read my third novel, NOS4A2. It was just a rock-your-sneakers-off, amazing performance. I had to have her for The Fireman and fortunately, she was able to find time in her schedule. It’s such a corny thing to say, but it’s true: When you listen to her tell the story, you can see the whole movie in your head. She plays those characters so well and creates such an incredible sense of drama. I love Kate. I think she’s a rock star.

A: One more question. You’ve been a huge proponent of audiobooks, which is one more reason we love you at Audible. Could you say a little bit about what makes the listening experience so special?

JH: First of all, I love to hear a story. When I was a teenager, my favorite novel was Lonesome Dove, by Larry McMurtry, which is weird because

I’m not a cowboy. For some reason, that story really spoke to me. In my 20’s, my favorite novel was The Fixer, by Bernard Malamud. It’s a story about a Jewish man who’s railroaded for a crime he didn’t commit and thrown into a Russian gulag. I’ve never been to Russia, I’m not Jewish, I’ve never been falsely imprisoned, but that story really meant something to me.

Years after I read both of them, I suddenly realized I had listened to both on audio — and both stories were read by a guy named Wolfram Kandinsky. I got goosebumps all over when I discovered that was probably why they meant so much to me.

I did a series called Locke & Key about a haunted New England mansion full of enchanted keys. And not to be cheesy with the cross promotion, but after that comic book series was complete, Audible jumped on it and did a giant audio play of the whole story. The idea was to create a cable series you would imagine — that you would have a cable series for your ears. It was just an experiment, but it happened to be a very successful experiment that a lot of people had a lot of fun with and opened up the story to a new audience.

A: Sorry, I’m getting the “Wrap up right now.”

JH: We’ve got to be done? Anyway, audiobooks … awesome.

When I was in my teens, I tried a couple books by Elmore Leonard, but couldn't see what all the fuss was about. I didn't "get" Leonard until I listened to The Hot Kid, the story of a deadly Depression-era Federal Marshall who wouldn't mind becoming a legend. Arliss Howard's dry, laconic reading woke me up to the musical quality of Leonard's dialogue, which jingles and jives like shell casings falling on the desert hardpan. I've been an Elmore Leonard cultist ever since.

No one writes sentences like Denis Johnson. His line-by-line craftsmanship is too good to just stare at on the page. His prose begs to be read aloud, to be heard. It doesn't matter what he's riffing about: could be an emergency room at 3 a.m., could be a blood-drenched car wreck. All the real shocks are in the language itself, with its combination of bleak understatement and chilly, forensic attention to detail.

Lenny Henry does about eleven thousand different voices, all of them perfect, all of them hilarious, in what might be one of the world's only screwball horror novels. Anansi Boys is a Neil Gaiman story about what stories can be and how they can make the weak powerful and the powerful weak. It also includes several really fine jokes. The only thing better than reading a fine joke is hearing one, told by someone who knows how, and Lenny Henry knows how.