Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

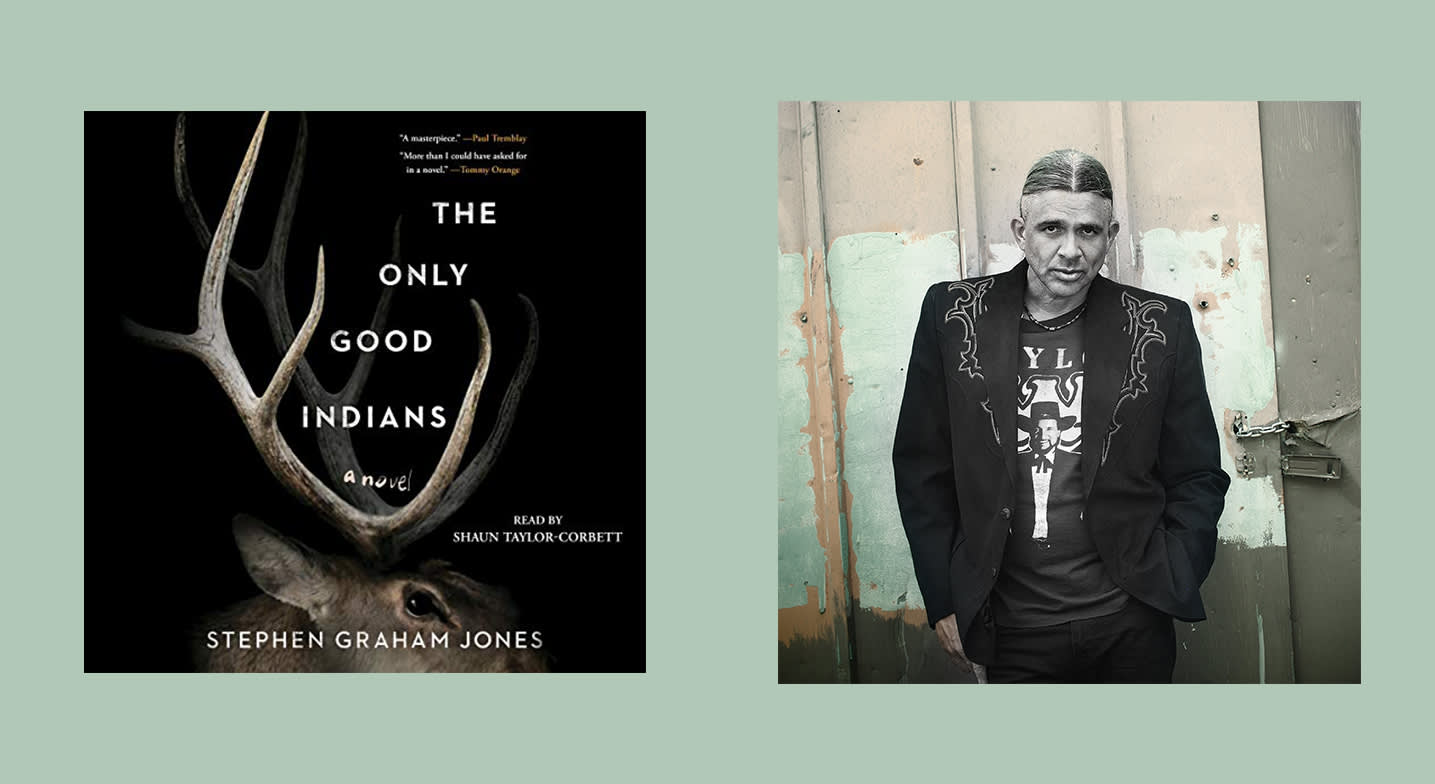

Nicole Ransome: Hi, I'm Audible Editor Nicole and I have the pleasure of talking with Stephen Graham Jones, who has won numerous awards, including the Bram Stoker Award, has been recognized by the National Endowment for the Arts, and is author of The Only Good Indians, one of the most talked about horror novels out this year. Welcome, Stephen.

Stephen Graham Jones: Thank you for having me. It's great to be here.

NR: The first question I want to get into is the title. It grabbed my attention when I first saw it. How did you choose this title?

SGJ: There's three parts in this novel, and this was a title for one of the parts. My editor had the idea of moving it to the book cover, to be the title of the novel. It was the right idea, of course. Quite often, for a lot of my novels, my editors and my agents have helped me with the titles because I get too close to it and I can't see, so they tell me. It was a title of a part, and of course it comes from that slogan in the 19th century, which if horses had bumper stickers, the bumper stickers they'd all have worn in 1870 would have been, "The only good Indian is a dead Indian," which of course I have issues with and want to push back against.

Horror lays eggs in your head that hatch at unexpected times.

So, in one way I wanted to push back against it to make it plural, but another thing I wanted to do was I wanted to interrogate what it means to be a good Indian in 2020. It turns out that there's not just a single way to be a good Indian, there's seven million different ways because there's seven million of us. It's not about how traditional you are, or how much you adhere to this, or how successful you are in this world or that world or in the middle of the world, or anything like that. It's about whether you define your own terms of success. If you reach those and if you're satisfied… “Good Indian,” it's like something that people lay on us and they say, "You have to do this, this, and this in order to count," but I think that's quite damaging and violent.

NR: Honestly, I understand, especially currently with a lot of the stuff that's happened. In The Only Good Indians, four Native American men are being haunted by a vengeful spirit. The way you set the spirit up? I thought it was great and I love ghost stories. Throughout the novel, there are many cultural and societal examples of stereotypes and expectations [of] Native Americans. As a Blackfeet Native American author, how important is it to portray the proper Native American experience while also sticking with your heart?

SGJ: It's probably less about being proper and more about being accurate. Maybe those are interchangeable terms, but some writers will get in trouble if they have an American Indian character in their story who is exhibiting poor behavior of one sort or another. People will say, "You shouldn't show that side." There's good and bad in every culture. Just to only show these upstanding citizens or whatever is just as damaging because that promotes the ideal that everybody's perfect, and that's terrible. That's just essentialism in the other [direction].

What I try to do on the page is I just try to do real people. Not necessarily people I know, but definitely agglomerations of people I know. I'll hopefully never be damaging, but I'll always at least strive for accuracy, if that makes sense.

NR: I like that. How much of your personal experience is influencing your writing?

SGJ: Oh, so much. With The Only Good Indians, there's a character, Lewis, who has this first kind of spooky experience when he's up on a ladder in his living room and he's trying to fix a light bulb in his ceiling. That's exactly me. About two years ago, maybe two and a half years ago, my wife and I and my kids moved into this house. We were renting this house and it had this light bulb, it still has this light bulb up in the ceiling that's like a haunted light bulb. The switch? It doesn't care about the switch. It just comes on at random times. You'll come in in the morning and it'll be on. We looked through every switch in the house and we can't figure out what's going on. We can't figure out if it's connected to the garage door or what's going on. We changed light bulbs and everything and it's just a haunted light or something.

So, Lewis being up on that ladder and messing with that light was just me being unimaginative, I guess, and writing down what happened to me. I didn't look down through the fan blades and see what he saw, but I did look down through the fan blades and think, "Is there something about the frequency of the spin that would allow me to see into another place?" That's where stories start for me.

NR: Wow. That's the funny story, because if you've seen the movie Parasite—have you seen it?

SGJ: Oh, yeah. Yeah, it has that light!

NR: With the light and the guy in the hidden room downstairs! Check your walls.

SGJ: Well, this house—we're not in it anymore, we were renting it—had these areas in the basement that were paneled off and it said, "Do not go in here." So, who knows, maybe something like that was going on.

NR: As soon as you said it, that was the first thing that I thought of. Like, "Oh, wow. Check the wall." As a huge horror fan myself, [I’m curious to know] what inspired you to write horror novels? How did you get into it?

SGJ: I grew up reading horror novels. Well, I grew up reading horror and science fiction and fantasy and westerns. I didn't discover literary fiction until my twenties, probably. But the thing I like about horror is that it can provoke a visceral reaction that the reader doesn't necessarily enter into a contract to give.

Let's say you're watching a monster movie or reading a monster novel. Some part of your brain, the way it defends itself against the dread and the terror, is it's always looking for the zipper in that suit. It always wants to say, "This is fake," or "This is not written well, so it must not be real," and stuff like that. You can fool yourself into thinking, "I've done it. I won against that horror."

But then at two in the morning you're going down the dark hall for a glass of water and you realize what was in that zipper—what was in that monster—and it might be worse than the monster itself. Horror lays eggs in your head that hatch at unexpected times. I really, really like that dynamic a whole lot.

NR: I agree, I also generally like to spook myself a little bit. It's always been one of my favorite things to do: watch horror movies, turn off the lights, set the atmosphere so I can really get into it.

But that leads into the next question. You write great and descriptive gorey and grizzly scenes. How do you get into that headspace? Is it like a setting of the atmosphere or is there more to it?

SGJ: When you do a gore scene, or there's some sort of intense scene like that, it's not always exactly about the moment when you see the viscera or whatever. Sometimes it's about the ramp going up there to the viscera. So you have to really control those beats going up to that corner where you're going to turn and see something terrible.

Like when you're watching Alien, say, and whoever is looking for the alien creeping around all those pipes, and it's all terrible in the spaceship. Part of that long slope of getting up to the scare of seeing the alien is Jonesy the Cat jumping out. That’s part of it. It allows us a pressure release valve and it also resets us and we're like, "Oh. Well, there's no alien," and then suddenly there's an alien. That's part of that long slope, and so, to me, it's not exactly about how well I describe the sheen and the smell and the heat of the viscera, it's often about the ramp getting up to that.

NR: I love that. I think that also ties into why I felt like your plot has such a great cinematic feel to it. That leads me into a question about the narration. Have you listened to the narration yet?

SGJ: No, I'm so anxious to. I've met the narrator, Shaun Taylor-Corbett, and he's so talented. We were so lucky to find a Blackfeet voice actor to do this. It’s such a wonderful pairing. We had a lot of talks before he recorded about how this character would speak, how that character would speak, and their intonations and their accents and stuff, and how they would twist things when they're saying it, and how they would [create emphasis]. I feel confident that this is going to be an amazing production. I'm so jealous that you get to listen to some of it. I'm probably having to wait until Tuesday.

NR: I know, the perks… With this audio recording, it was so dynamic. Shaun Taylor-Corbett really did such an amazing job getting those different like character voices. But one question I did want to ask, is… how do you fit so many characters’ stories in this plot? Because you're tracking the four Native American men, but you're also talking about the different characters that they come in contact with. It feels like you really get to know them, listening to the audiobook. When do you feel that the listener knows enough about the character to really feel for that character?

SGJ: That's a good question. When you're dealing with what I would consider an ensemble cast, what you have to do is, with each character, you have… like Hemingway, when Hemingway writes a short story, he'll go into a bar and instead of his character, or his narrator, or his point of view saying, "The bottles are like this, the mirrors like this, and smokes like that, and the doors like this, the bartender's like this,” he'll find a cigarette burning down in an ashtray and he'll zero in on that and he'll talk about that cigarette in a way that evokes the whole everything around it. The mirrors, the bottles, the bartender, the door, the light, the smoke and everything.

I thought, "What if Jason Voorhees came to the reservation and ran into an Indian girl? Would that be completely different for him?"...That's what The Only Good Indians is for me. It's not Jason takes Manhattan, it's Jason goes to the reservation.

That's what you’ve got to do when you're doing a lot of characters. You don't have time or space to burn a lot of pages establishing each character. You have to find that burning cigarette in the ashtray that completely defines them and get on the page as quick as you can, and that will let that character be real. Then once that character is real, it's like they start climbing their own arc, and I just have to document what they're doing.

NR: So you breathe life into the character, but they blossom on their own.

SGJ: They do. A good example of that in this novel would be Victor Yellowtail, this tribal police officer. He didn't start out at all. He just was in the background, but then somehow he came alive and just did all this stuff that I didn't expect him to do. I was completely satisfied and thrilled he was doing it, but I'm like, "Who are you, dude? You weren't supposed to be here."

NR: Wow. Well, has listening to your audiobooks impacted how you write or your relationship with your work in any way?

SGJ: It does. I haven't listened to all of my audio books, but probably my favorite until this one has been Zombie Bake-Off. It's about soccer moms versus zombie wrestlers. They found a voice actor to read it who kind of has that wrestling-announcer delivery, and he inhabited the space so well.

But yes, it has. Listening to my work being produced like that has, I think, lodged something in me that changes the way I write. Specifically, it's probably changed the way I do dialogue tags, because voice actors are so competent with distinguishing this character from that character with their intonation and accent and pacing and all the different tricks they do to achieve some sort of unique diction that the tag becomes superfluous. The he said, she said, all that, becomes completely extra. I hear that extra in the audio production sometimes, and I think, "I shouldn't have done that."

But at the same time, the audio version and the written version, they're distinct versions. They have the same script, but they're different too. I hear it myself when I'm doing a reading and I'm at a podium with an audience of 400 people and I'm having to say, he said, she said, he said. I'm like, "This is ridiculous. Why did I put all of these tags in here?” Because I'm not doing voices as good as a narrator would, but I can differentiate a little bit.

John Scalzi, the science fiction writer, he talks about this too, about how audio productions have changed his writing style. I think it's changing all of our writing styles, really, because audio is right at the front edge of everything. Everybody's dialing up books and I think it's really cool how it's changing what's happening on the page.

NR: Oh, I love that answer. I saw that you're a big horror movie fan. One of the questions I wanted to ask you is, do you find yourself channeling any horror TV or movie villain that you really like in any of your writings or any of your work?

SGJ: I do. I think it's unavoidable for me. I remember years ago someone asked me, "Where did you grow up?" the only thing I could think of was, "I grew up in MTV," because that's my media landscape, back when it was different.

With The Only Good Indians, the seed in my head, what I wanted to do with it, was, I thought, "What if Jason Voorhees came to the reservation and ran into an Indian girl? Would that be completely different for him?" Of course, he's trademarked. I can't use his hockey mask, so I had to come up with a different slasher, one that made sense for the story. But really, that's what The Only Good Indians is for me. It's not Jason takes Manhattan, it's Jason goes to the reservation.

NR: Okay. Jason Voorhees is one of my favorite characters as well. I do love the Friday the 13th movie.

SGJ: …The one thing that maybe slasher fans can take away… I've been watching slashers forever and ever. They're like the closest genre to my heart, but the one issue I've always had with slasher films is at the end of the movie, when the final girl quits running and turns around to face the slasher—Jason, Freddy, whoever. Generally at that final part of that final battle she has to basically muscle up. It's who can swing the machete the hardest or who can take the most damage. She generally wins the day.

However, she's also, I think, trading in the characteristics that have gotten her this far in life, and she's taken on conventionally male characteristics of muscles. It’s a stereotype that we do with men and women which we should get past. I wondered what would happen if the final girl was able to win the day not with muscles but with compassion. That's what I want people to take away, that women, in order to win the day, don't necessarily have to stop being themselves…

NR: Wow. Because you talked about a lot of the stereotypes that are associated with being a good Indian or a good Native American, what would you say for other Native Americans maybe listening to this story? What would you want them to take away from this story to feel sure about themselves as well?

SGJ: I would want people to take away that Indian fiction, Indian stories, Indian art doesn't always have to deal with identity politics, or history, or tragedy. We can be characters in any kind of story. We can be the good guy and we can be the bad guy.

If you see fiction or literature as a tree, the marketplace wants us to stay close to the trunk, like we're still in need of shelter, or we're still young, still figuring things out. But my feeling is that we can run as far out on the thin branches as we want. We can go into the sub, sub, sub genres of horror or science fiction, or whatever. We don't have to always be talking about what happened in 1870 or something. We don't have to leave that stuff behind at all—we can still write about it, but we don't have to. We don't always have to be dealing with that stuff. We can just be in good stories.

NR: As a Black American, it's also pretty hard to find a lot of African American horror writers as well. So that speaks and resonates with me too. I completely understand that. You want more genres, you want more diversity, you want to see it all.

SGJ: Yeah.

NR: …I want to go back to the title of your novel. When I grew up, we were generally taught that “Native American” was always the term to use and never “Indian.” I know that it also comes from the quote, but for people like me who might also get shocked at seeing it, like, "Oh no!”—what would you want to say to people who are just seeing the title and haven't read the story?

SGJ: The people who push back against the term “Indian” are right to push back. It's an inaccurate term. But the way I look at it is, I grew up “Indian” and it's hard for me to become “Aboriginal” or “Indigenous” or “Native.” The one term I've always liked that I prefer is “American Indian” because I like “Indian” to be at the center of the noun and “American” to be the adjective, modifying. It re-centers things.

I think “American Indian” is an accurate term, or more accurate anyways. “Native American” is not wrong at all. A lot of people still use “Native American.” Lately, what you hear more and more is “Native.” People just say “Native” instead of “Indian,” either as an adjective or a noun, and that completely works. Sometimes I can dial over to that.

But usually when I'm talking about myself, I'll fall back on “Indian,” just because it's weird for me to be something other than “Indian,” if that makes sense. The characters in The Only Good Indians have a page or two where they deal with this, where the younger generation is talking to the older generation, “But what term do we use, which is correct?”

Maybe I'm just a generation that still uses “Indian” or hasn't been able to change my thinking over to “Indigenous” or “Native” or something, but none of the terms are wrong, and none of them are more correct. It's just what you're comfortable with.

NR: …I love that answer. So are there any horror genre or scenes that you wish to explore in the future or the near future that you don't think you have yet?

SGJ: I've had the idea in my mind for a while for a possession novel that I'm too scared to write, so maybe I'll get the nerve to write that novel. Also, I noticed that I've written a whole lot of vampire stories, and I think those are probably kind of me doing test runs into the vampire genre to see if I can go the full distance…

NR: I'm a big vampire fan. I do like the vampires, not really the Twilight ones, but I do like the classic scary vampires. I used to watch Nosferatu a lot when I was younger, which was so weird.

If you write a possession, you will have the first listen on me because I was a big fan of The Exorcist. That's one of my favorite books and movies that I can watch all of the time since I was a kid. I would love a possession novel.

SGJ: I just got to get my nerves together and be able to push through it.

NR: Are you scared of possession?

SGJ: Terrified of it. I think it's not a religious fear. I think it's a specifically Indian fear of being inhabited, because the whole Americas were inhabited. A possession novel distills that down to a single bedroom and it makes it really uncomfortable.

NR: With this, we can start wrapping up, unless you have anything else that you want to let the listeners know, to get prepared for?

SGJ: No, just I hope everybody enjoys The Only Good Indians. I hope they're scared. I hope people stay up late reading it. That's what every horror writer wants.

NR: Yes. I had a great time getting to know author Stephen Graham Jones, whose new audiobook The Only Good Indians is available on Audible now. Thanks, Stephen.

SGJ: Thanks for talking. It was great.