This interview was originally published on audible.co.uk.

Cognitive neuroscientist Gina Rippon has spent much of her career dedicated to debunking the myth of a male versus female brain. Now, in Off the Spectrum, she has turned that same line of questioning towards autism spectrum disorder. Gina discusses why autism has largely been considered a “male condition,” leaving behind countless women and girls who go undiagnosed—or who were never evaluated in the first place. Below, Gina shares some of the most surprising findings in her research, and how we can best advocate for the next generation.

In your book Gender and Our Brains, you debunk the myth of a male versus female brain. How does Off the Spectrum and your work with autism converge or diverge with those findings?

That is a great question! Both books tackle the issue of "gender gaps," the causes of world-wide differences between females and males in personality, performance, achievements and power. But also, in the case of autism, the statistics that show that many more males than females are diagnosed with autism (the ratio has been as high as 15:1 but is currently quoted at 4:1). Why are there these female/male differences? Can we just "blame the brain"?

Gender and Our Brains looked at brain-based explanations for gender equality gaps—the under-representation of women in science, for example. How true is the centuries-old assertion that there are two types of brains, female and male, which are inextricably linked to the biological sex of their owners and invariably determine how we think and feel, and therefore what we can do with our lives? A review of decades of psychological and brain-imaging research concluded that this notion was a myth that needed busting.

What about autism? Could it be that, in the rarer reaches of human behavioural differences, biological sex does indeed exert a determining influence in this particular brain-based way of interacting with the world? How could I square the circle of claiming there were no sex differences in the brain (which, actually, I didn’t) with the fact that there were clear sex differences in the prevalence of autism, a genetically determined, brain-based disorder, much more common in males than females? These sex differences in autism were so clear that researchers have been hunting for a "female protective effect" (in a rare example of claiming something positive for female biology) or have proposed that autism arose from the possession of an “extreme male brain.”

And that was the origin of Off the Spectrum. Did the world of autism brain research actually show genuine sex-based differences, which could explain why there was this male prevalence? My initial deep dive to check this out immediately revealed a problem. The notion that autism is a male problem has been so deeply embedded that the sex-difference research I was hoping to comment on was virtually non-existent! And a deeper dive revealed that this male bias was also influencing who was even assessed as autistic in the first place, with a powerful male filter determining how they were assessed.

So, both books challenge sex and gender myths in different ways: Gender and Our Brains that brains can be "sexed," and Off the Spectrum that autism is a male problem. They both reveal that unchallenged beliefs can distort the scientific research process and that this can "leak out" into public consciousness and prop up misleading stereotypes.

In your opinion, what will it take to close the gender gap in scientific research?

I’m assuming you mean the gender gap in scientific research into autism. (Although I could rant lengthily about the under-representation of women in science and scientific research!) A core problem is the biased recognition and assessment of autistic females. Boys are 10 times more likely to be referred for an autism assessment than girls, and twice as likely to be diagnosed as autistic than girls. And a high percentage of autistic females are not diagnosed until well into adulthood. For research, this means that there is a very limited number of diagnosed females to be included in research studies. So the so-called "gold standard" autism assessment schedules need to be amended to more accurately recognise autism in females, for example by using gendered norms, but also by incorporating previously unrecognised aspects of autism which are more characteristic of females.

"Until there is a wider understanding of the lived experience of all autistic people, we will never get a clear view of the whole spectrum."

In addition, researchers need to ask better questions and to include autistic participants (both male and female) in designing their studies. What aspects of your daily life are most affected by your autism? Do you try to hide your autism? Until there is a wider understanding of the lived experience of all autistic people, we will never get a clear view of the whole spectrum.

What has been the most surprising thing you’ve learned in your study of autism?

Obviously, the extent to which the notion that "autism is a male thing" had infiltrated and biased all aspects of the autism story, but especially that, up until recently, very many studies of the autistic brain had only been using male participants.

An additional alarming rather than surprising finding was just how many barriers stand in the way of autistic women obtaining the diagnosis they need, all the way from teachers believing that only boys get autism, to clinicians reaching for a medley of other diagnoses (and medications) until arriving at the only one that has ever made sense, that of autism.

With respect to my own research, it has been exciting to be able to harness breakthroughs in brain-imaging theory and research to start to build a better picture of the very different ways in which autistic brains work, and to begin to link these to the many different patterns of behaviour which characterise the autism spectrum.

It was also intriguing to discover the story of Grunya Sukhareva (spoiler alert!). Twenty years before the so-called "fathers of autism" began publishing, she was clearly outlining the characteristics of autism and, importantly, drawing attention to differences between the boys and the girls she was describing. How different the history of autism might have been if she too hadn’t been written out of the autism story!

How can parents and caregivers best advocate for their young daughters when seeking a diagnosis?

Arm yourself with evidence! Be prepared to confront stereotypes and unchallenged beliefs—don’t be disarmed by claims that “autism is a boy thing,” “she can’t be autistic, she makes eye contact/has friends,” “she’s just shy,” etc. The autism community is well served by valuable online resources, especially from organisations such as The National Autistic Society or Autistica, which offer valuable case studies, statistics, etc.

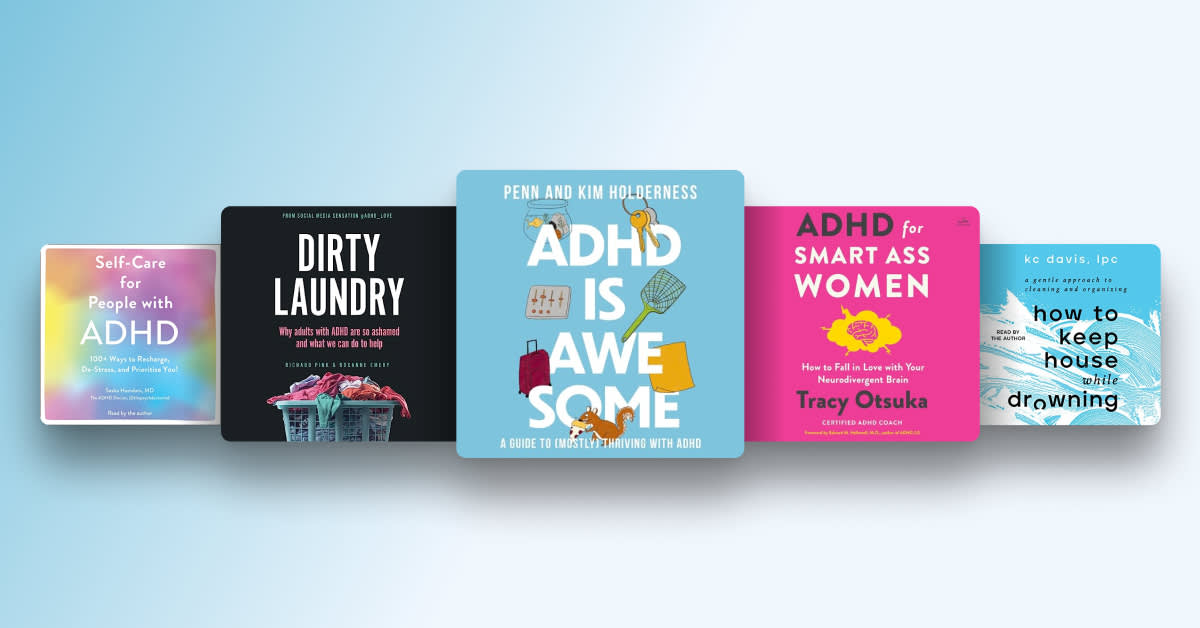

Read books! There are also (of course) many valuable books, ranging from the textbook type to self-help and biographical material. At the end of Off the Spectrum, I provide a list of hugely insightful personal testimonies which describe the personal struggles of autistic females and the barriers they had to overcome—these should resonate powerfully with parents and caregivers seeking a diagnosis for a young girl. And I have provided as much research evidence as I can throughout the book, which should help draw up requests for assessments (and appeals against refusals!).