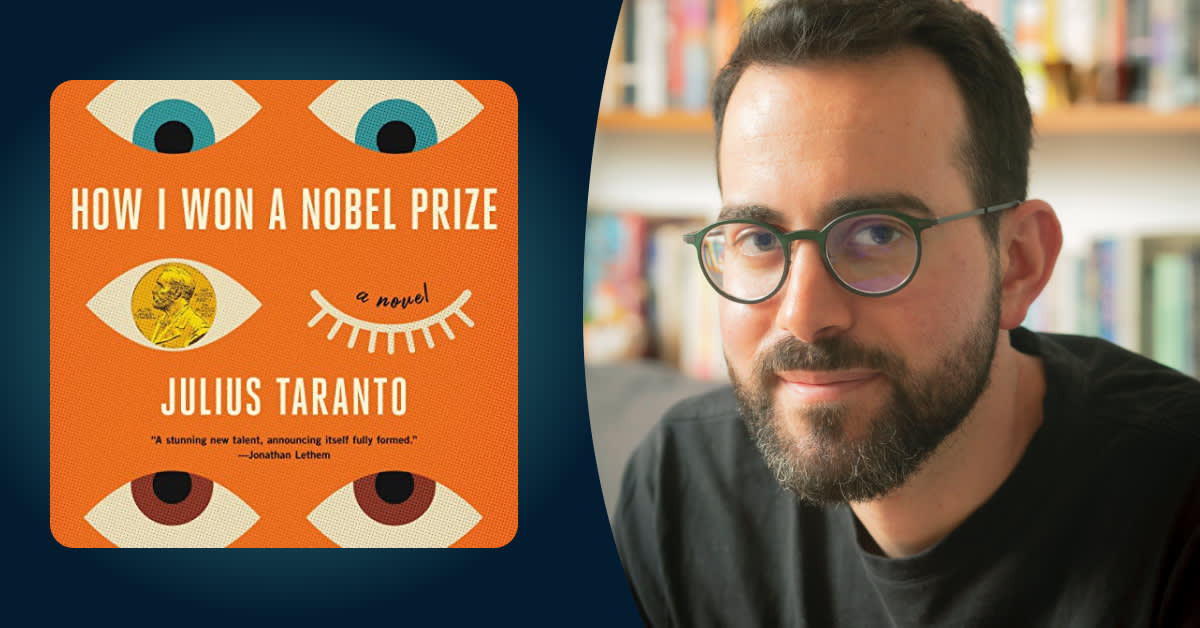

In Julius Taranto's debut novel, a physics grad student reluctantly accompanies her disgraced mentor to an island university where other "canceled" academics operate with impunity. Helen's difficult choice was prompted by her passion for her work, while her partner, Hew, has fewer scruples, leading them to increasingly different fates in the world of the novel. We asked the author about his influences and inspirations behind How I Won a Nobel Prize, which is read in audio by stellar performer Lauren Fortgang.

Jerry Portwood: As we all know, you have not won a Nobel Prize, but you sure took a shot with that title. How did it come about? As a debut novelist, were you worried about ... say, hubris?

Julius Taranto: I love the winky hubris of it. I hope the title, plus Lucy Kim’s amazing cover design, invites people in on the joke and hints at the difficulty of the problems the book addresses. If I do win a Nobel Prize ... let’s say, I’ll be mildly surprised.

You studied law and so obviously have thought deeply about morals and ethics. Is that what inspired you to tackle such a thorny subject with such insight?

I wanted to tackle this subject in part because I want readers to feel that our absurd dilemma—the truth that we have to love even the people we hate, even the people who do terrible things—can be pretty funny. I’m pretty sure everyone thinks deeply about their morals, but maybe it’s true that I like thorny questions more than most. Running headlong into thickets seems like a good way to learn who we are as individuals and a society—and you often have to do that in both law and in fiction.

Literature and law are connected in the sense that, at their core, they are both about justice, about giving every person their due. In law, the task is often public-facing and rhetorical—you’re trying to persuade others to reach a judgment under publicly agreed rules. In literature, you’re giving people what they deserve in a different way, a sort of private justice, by recognizing and representing the parts of people that are very real but too uncertain, specific, and irreducible for generalization and public judgment.

I don’t think it’s an accident that when a fictional character feels true and sympathetic, we say the author did the character “justice.” So I hope readers will emerge from the thicket of questions in this book not with certainties—which I really don’t have—but instead with the surprising feeling that it may be possible to see the world in a way that does justice to all of these characters, even though many of them disagree with and hurt each other.

Literature and law are connected in the sense that, at their core, they are both about justice, about giving every person their due.

Some might say, sure, a white, straight, cis man wrote a book that skewers Me Too and so-called “cancel culture”—and he chose a female narrator/protagonist as his shield. But it's also big-hearted and sly in its judgments and eviscerations. What would you like to say to potential naysayers and/or the folks who might love your novel because it’s taking on this topic so directly?

I hope that any anxiety that people may feel about the combination of author and subject will be released, in the form of laughter, when they listen to the book. I won’t pretend I wasn’t awfully anxious about this myself. My friends and family, too.

One of the best parts of starting to show the book to people has been hearing their delight (and relief) that the book seems to have found a way to talk about the culture wars and other knotty topics without becoming a polemic. Novels are not usually the best form for certainties, so I actually don’t think my book does much in the way of skewering—or if it does skewer, then it skewers everyone while also being warm to everyone.

In this metaphor, I’m realizing, the whole American political spectrum is on a single kebab. Take a bite. We’re delicious.

It sounds like it was pretty quick from when you got your idea, wrote your manuscript, and found an agent. Was it really that simple? Any advice to aspiring writers? How did you sustain the nerve to take this to the finish line?

Oh my—I hope I haven’t given the impression that getting a first novel published was simple or easy. For this book, it’s true that I was incredibly fortunate to have it fall into the right hands in ways I never could have planned. That good luck followed over a decade of drafting manuscripts, multiple entire novels, that I couldn’t sell. It was profoundly demoralizing. I don’t think I would have kept going except that I continued to feel like my time on Earth was not well spent without writing.

I don’t have any advice to aspiring writers except that you probably have to be as serious about your work, because it is really difficult, as you are lighthearted about the insane, hilarious arbitrariness of getting published. The market crushes everyone. Without a sense of humor, it’s hard to peel yourself off the mat.

I don’t think I would have kept going except that I continued to feel like my time on Earth was not well spent without writing.

Last question: Do you have a favorite listen from the past year to recommend and why?

I listen to a ton of audiobooks and get very excited when I hear writing that has found its perfect narrator. One favorite recently was my friend Charmaine Craig’s incredibly clever and gutsy novel, My Nemesis. She narrates the audiobook herself with characteristic brilliance and verve—no one else could have opened up the meaning of her book the way she did. It helps that she was an actor before becoming a novelist.

I also really loved the audiobook of David Milch’s memoir, Life’s Work. Milch had a wild life and made some great art. His memoir, written with his family’s help during his descent into Alzheimer’s, is among the most insightful, self-aware, and moving literary memoirs I’ve read. Michael Harney narrates the audiobook. He’s a wonderful actor who worked on Milch’s TV shows, and he captures Milch’s range and force of personality with enormous heart and charisma.