Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

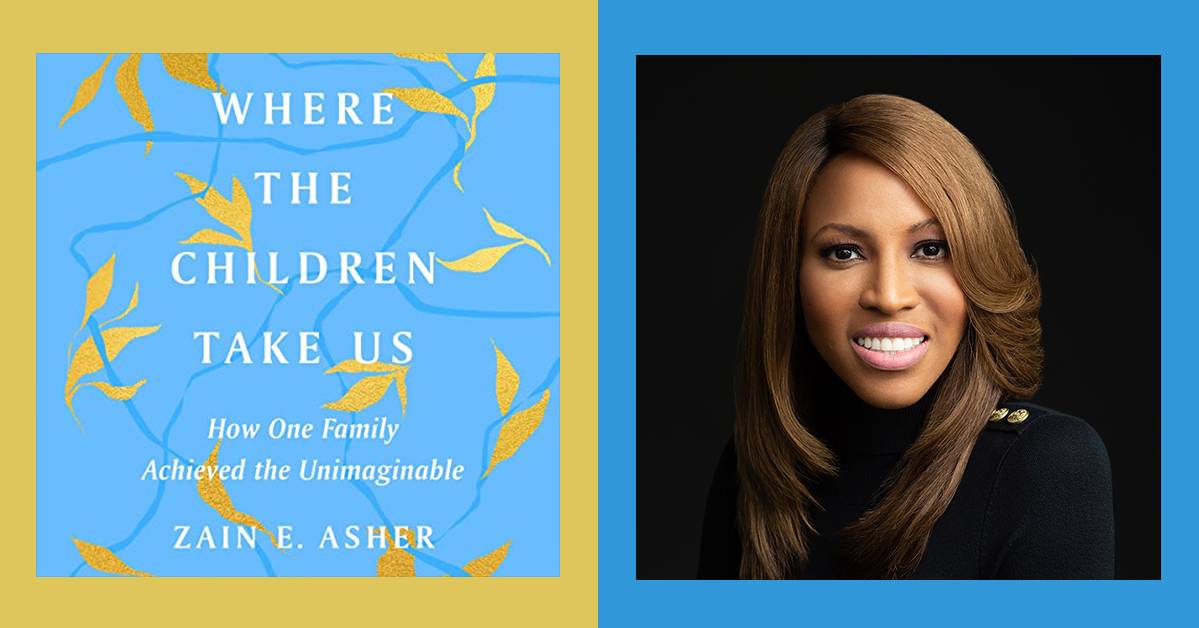

Katie O’Connor: Hi listeners. I'm Audible Editor Katie O’Connor, and today I'm privileged to be speaking with Zain Asher, CNN International anchor and host of One World with Zain Asher. Today, we'll be discussing Zain's memoir, Where the Children Take Us, a remarkable story of resilience and her mother's journey to raise four exceptional children. Welcome, Zain.

Zain Asher: Thank you. Hi, Katie. Thank you for having me.

KO: Thank you again for joining us. And let me just say I loved your memoir. Learning about your mother's tenacity and determination to really go above and beyond for her children in the wake of such a heartbreaking loss, the loss of your father, was truly remarkable.

Can you tell me, why now? Why was this the right time for you to tell your mother's story?

ZA: Yeah. So, when I wrote the proposal to submit, I just had turned 36 years old, and that was the same age that my mother was when she got that horrific phone call. And, you know, just for people who obviously haven't read the book or listened to it, in 1988, September, my mother was in the living room and she's waiting for a phone call from my dad. And my dad and my brother were on a father-son road trip. It was a long-distance road trip, and they were set to come back to London that day and my mom was going to pick them up from the airport.

So she was literally waiting for a call from my dad to say, “Hey, you know, we've landed at Gatwick or Heathrow Airport, come and pick us up.” So my mom got ready that day, because she knew what time the flight was set to land and she just waited. She waited for the phone to ring, and the phone never rang. It was strange, and so she just assumed that maybe the flight had been delayed.

And then she waited and waited and waited and waited, and there was still no phone call. And she was getting a bit annoyed because, you know, even if the fight is delayed, of course, my dad could still call and let her know that. And then at around 6:30 in the evening, the phone finally rang, and she ran to go and answer it, but it wasn't actually my dad on the other end of the line.

It was an extended relative in Nigeria, which is where the father-son road trip was taking place. And the voice on the other end of the line said to my mother, "Your husband and your son have been involved in a car crash. One of them is dead. And we don't know which one.” And, you know, that phone call, that moment almost destroyed her, having those words spoken to her, those two sentences spoken to her.

"I didn't really know my dad, and I've sort of spent my entire life searching for him. And in a way, through these interviews and through this book, I feel as though I finally found him."

And that moment, she tried to cling onto hope, thinking that, perhaps, since the person on the other end of the line obviously didn't have that much information, maybe they'd made a mistake, maybe, you know, even though there was obviously a car crash, maybe they were both injured but they were both ultimately okay.

But she went back to Nigeria ultimately not knowing. It turned out it was my father who had passed away. And my parents were the loves of each other's lives. I mean, my mom really describes meeting my dad as quite simply nothing other than love at first sight. She was 14; he was 16 years old. He was the first man that she had ever held hands with, kissed, you know? And they had this just incredible bond at such a young age.

And so when I turned 36 and I was the age that my mother was when she got that phone call, plus I had children myself, it really dawned on me the magnitude of what my mother experienced. Obviously, growing up, I always knew about that phone call. I was five years old at the time, but I always knew that my mother had gone through, quite simply, an emotional earthquake. But when I turned 36, and when I became a mother myself, that is when I really began to understand what she'd endured.

KO: Yeah. I completely understand that. I think you start to think as well, what would I have done in those situations? How would I have reacted? And I know at first you describe in the memoir that your mother retreated, and she really had to wake herself up to start to show up for you guys every day. Because not only did she have three children, she was also pregnant with your younger sister, and then running her pharmacy as well, just to keep everything going for you guys.

You mentioned your parents’ love story. That was one of my favorite parts of the memoir, was just seeing the way that they were drawn together. The way that your father kept finding her during the civil war in Nigeria as well, just tracking her and her family down. You could really feel their love. And what you described is so vivid, those early days in Nigeria, but also when they first are living in London. Did you interview her for the memoir? Can you talk to me about what your research was like for your writing process?

ZA: Yeah. So, I was five years old when my father passed away. So a lot of the chapters that have to do with my dad dying or that phone call was pieced together through interviews with other people. I really only have one main memory of my dad, which I'll get into in just a moment.

But yeah, I interviewed my mother. And it was a really difficult thing to interview her, because it was the first time she'd really gone deep about what that whole experience was like. And so she had to set time limits on our conversation. She would only be able to talk to me for about 10, 15 minutes at a time. And she'd set the timer and then when the buzzer would go off, we'd have to be done for the day because it was just too painful to relive. And she'd never really gone to therapy or processed what happened to her.

And so she was obviously one person. My brothers, you know, were also a key part of this as well. And then I found extended relatives, people who were in Nigeria and who went to go and see my brother in hospital. There was one guy called Mike Obiekwe who was, and I love just saying his name out loud because his job, he was 19 years old at the time, and he's an extended family member, but his job was to, while my mother was coming over from England, just to sit with my brother in hospital and to play games with him.

And, you know, he, my brother, was 11. And so you’ve got this 11-year-old boy who had just lost his father in a car accident. And so you kind of want to engage with him and distract him and make him think about anything besides what is actually, really happening. And so his job was just to get my brother to laugh, get my brother to smile, and just have him not focus on the fact that he had lost his dad.

Although, to be perfectly honest with you, my brother didn't actually know that my father had passed away for quite a while. While he was in hospital, he would ask people, "Where’s dad?” You know? And people would tell him—they were too afraid to break the news to him—they would tell him that my dad was recovering in another hospital room. And so it was a while before he actually knew the truth.

So Mike was another person that I spoke to. He's about 50-plus years old now or so. And he had so many details to share with me about what the hospital was like, and the sort of condition that my brother was in, and obviously my mother coming into town. And my mother, yes, was grateful that my brother was okay, but at the same time now had to suddenly bury her husband. And so she was very much preoccupied with that.

And there were uncles as well. My mother's brothers as well, who were around at the time, who knew my dad very well. And we had actually all traveled to Nigeria initially together for a family wedding, and then the idea was that my brother, Chiwetel, and my dad would peel off afterwards to go on this father-son road trip.

So there were many family members at the wedding who saw my dad a week before he passed away. So there were so many extended family members that, a lot of whom, by the way, I hadn't spoken to in a very, very long time, that I got to reconnect with. And it was a wonderful thing doing these interviews because I didn't really know my dad, and I've sort of spent my entire life searching for him. And in a way, through these interviews and through this book, I feel as though I finally found him, you know? So it's been quite the journey getting to know him for the first time.

KO: Yeah. That's beautiful. I really admire you and I admire your mother for what she was able to do with her family. How does she feel about the memoir? How does she feel about it being out? And how do your siblings? What's been their reaction to your family's story now being out in the world?

ZA: The first chapter of the book is very painful for people in my family to read. Like, very painful. And so it took my mother a while to actually have the courage to actually sit there and read Chapter 1. Because, as I say, she never found a way to process her grief. After my dad passed away, she just avoided really speaking about him.

My sister actually said to me—I sent my sister a video that somebody had sent me of my dad speaking at a christening in like 1985, 1986, a few years before he passed away. And he was the kind of person that could entertain a crowd quite easily and could give an impromptu speech. People would say, "Okay, Arinze, you get up in front of 300 people and you give a speech with no notes," and he would be able to do it and everybody would be laughing and whatever. And so somebody had a video of my dad doing this and just entertaining the crowd and everyone laughing and joking and whatever. And I sent it to my sister, who wasn't born when my father had passed away. My mother was pregnant with her. And she said it was the first time she'd ever heard the sound of my dad's voice.

KO: Wow.

ZA: Because everybody in my family, like nobody spoke about him. Nobody, like, processed. Everyone just sort of buried it within themselves. And so Chapter 1 is quite painful for my siblings and also my mother to read. However, the book is, and we'll talk about this, it's ultimately a story of hope. There is so much to celebrate, especially in how my mother raised us and what she was able to achieve. I mean, this is somebody who was a widowed immigrant living in South London, didn't have much money, whose husband died tragically in this car accident. And yet through her unrelenting discipline, her hard work, and just the fact that she's got this tough-love fighting spirit, she manages to raise a CNN anchor, an Oscar-nominated actor [Chiwetel Ejiofor], a doctor, and a successful entrepreneur.

So when I talk about how my mother did that, there's so much there to celebrate. And that is something that I think has brought a lot of joy to every single member of my family, because we are all so grateful for, and proud of, my mother in terms of what she's achieved.

KO: As you should be. And sometimes she did take extreme measures in her parenting, which was fun to listen to, hearing about when she literally cut the cord on your television at home to help you focus more on your studies. She got rid of the house phone and installed a payphone instead, again to help you concentrate.

But she also, when you were experiencing bullying and racism at school, she removed you and sent you back to Nigeria for two years to live with your grandparents. She was always willing to sort of do whatever it took to make sure that you guys had that solid future that she wanted for you. Now that you have kids of your own, I'm curious, which parts of her parenting are you hoping to incorporate into your own style and maybe which ones are you like, I think I'll skip that?

ZA: So, initially after my mom came back to England after my dad passed away and after she buried my dad in his village in Nigeria, she was going through an extreme period of deep, deep grief. I mean, it was just such a dark time in our lives because she really wasn't able to be a present mother to us. It was almost as though we didn't really have a mother or a father for a few months. I mean, she would just lock herself in her bedroom and just scream and cry and wail on the other side of the door.

"Through her unrelenting discipline, her hard work, and just the fact that she's got this tough-love fighting spirit, she manages to raise a CNN anchor, an Oscar-nominated actor [Chiwetel Ejiofor], a doctor, and a successful entrepreneur."

And it was only when my eldest brother, Obinze, just basically started going off the rails because he didn't have a father figure in his life. He didn't have any kind of parental guidance. And he ended up getting expelled from school, ended up hanging out with the wrong crowds, ended up getting into fights, yelling at his teachers, insulting them. It was so out of character because, prior to that, my eldest brother, to be perfectly honest, was kind of a goody-goody two-shoes, you know? But what happened to dad just, I mean, it just, it broke him.

And so when he gets expelled from school, it was this big wake-up call to my mom that her family's future was hanging in the balance and she had to do something. And my grandmother came over from Nigeria for a while and said to her, "Listen, I'm so sorry that this happened to you. I'm so sorry your husband has passed away in this horrific manner. However, you cannot neglect your children. It's just not acceptable. You can't just leave them to raise themselves."

And so at that moment there was this kind of turning point in our lives because my mom actually began to, especially after my brother got expelled from school, she began to roll up her sleeves and make changes around the house. She decided that there was going to be structure, that there was going to be routine, that there was going to be a much more heavy focus on academics in our household. And that meant, for example, she asked my teacher for my school syllabus to figure out what I was going to be learning in school in, say, a month or two months from then, you know, times tables, telling the time, that kind of thing. And she would teach it to me at home beforehand. And that was huge for me because I, even as a young child, I really did not enjoy going to school up until that point. I found school boring. I didn't feel that I belonged there. Also, I was a minority. I was one of the only Black kids in the school as well. And so I just didn't enjoy going to school at all.

When my mother began teaching me in advance, I would go to school and my teachers began to shower me with praise. They began to think that I was much, much smarter than I actually was. And they began to treat me as a role model, and I had all these sort of awards. I'm only seven years old at the time, but I remember we had this chart of gold stars and I had way more gold stars than all the other kids because my teachers thought I was so smart.

And that changed my ability to enjoy school. And it fueled my desire to go home and want to study some more. And part of doing well in school, I think, is enjoying school. And my mother had found a way just by helping me do better to get me to enjoy school all that much more.

And I think the other thing that she did that I loved is she would find newspaper clippings of Black success stories. She would look in various newspapers and see an article of a Black person, especially if they were of West African origin, who was doing really well in their chosen fields, and she would cut out these newspaper clippings, and she would just plaster them to our walls so that we would come home from school and we would see article after article after article of Black people who were thriving, who were soaring in their careers.

And there's a saying that the only thing that can hold you back in life is the perception you have of yourself. And my mother changed that perception for me. I always say this: regardless of your race, or your background, your religion, or your age, everybody has a tape that plays in their head about what they can't really achieve, what they can and can't achieve. The greatest thing that my mother did for me was change that tape through seeing so many examples of people who look like me, who were minorities, some of whom were women, not all, but who were doing incredible things. And so it gave me so much more confidence. It really upended my view of what it meant to be Black and what Black people were capable of.

KO: I loved hearing about this thing that your mother did for you all, this “uplifting” as you were calling it in your memoir. And I wanted to know what it means to you to know that you are now one of those examples, you are one of those Black success stories that other parents can use and have their children turn to? I think about the way that your village Enugu celebrated when you got into Oxford. The fact that after your grandmother's funeral, you and your mother traveled to the school that she had founded there, and you got to be the guest speaker. What is that like knowing that you're that symbol for especially young girls?

ZA: My God. Katie, you're going to make me cry. Oh, my gosh. It's so powerful, because I grew up at a time when, I mean, my parents came to the UK in the early 1970s. And this was at a time when England wasn't the most welcoming place for immigrants, to be perfectly honest. There were signs that said, “Keep England White,” you know? And that was a common refrain among far-right leaders.

And so yes, I was born in the eighties and I really came of age in the nineties, and things were better, but it certainly wasn't like it is today. I'm not saying that things are perfect today, but it was certainly better than the seventies. There was still a lot of racism, you know? I talk in my memoir about us at school, having swimming lessons every Wednesday. And every single time I entered the swimming pool the other kids would scream and cry because they thought that if I was in the pool, then the water would turn brown.

And so just to sort of come from that kind of environment and to grow up with that. And part of the reason why my mother searched for all these Black success stories is because I was having kind of a hard time in school with racism and all of that, and so she wanted to show me a different type of image of what Black people were capable of and boost my self-confidence.

And so the idea now that I can do that to someone else, it's incredible. I mean, I can't even comprehend, you know? It's just amazing to me because I had that growing up in a way because my mother found these cutouts. But I truly believe that if she hadn't done that—because part of success is about confidence. It is about believing in yourself. I didn't touch on this in the book, but there are lots of people who are capable of getting into Oxford but just don't apply because they think that Oxford is this magical place and it's not really for them.

And the fact that I have seen image after image of people that look like me who are doing remarkable things, it gave me the confidence to apply to a place like Oxford. So all of that, seeing role models, seeing these uplifters, as I call them, really changed my life. And the idea that I can change somebody else's life is an incredibly powerful one.

KO: This whole journey of this whole memoir, just seeing where you as a family started to then everything that you were all able to accomplish, I'm sure it's very surreal at times.

You mentioned everything that your mom did to sort of help you get ahead in school. And she also started a book club for your older brothers in an effort to keep them on track. And I love how one of your brothers, the Oscar-nominated actor, Chiwetel Ejiofor, when he got interested in the performing arts, your mother then ran out and got herself Shakespeare so that she could start reading and understanding the plays and running lines with him. So you were constantly surrounded by great literature. And I'm curious, who is your favorite author?

ZA: You know, that's such an interesting question because even though my mother taught us about these Western literary giants, like, for example, Rudyard Kipling and Jane Austin and Mary Shelly and Charles Dickens, and the list goes on. The fact is, in those stories, there weren't very many people that looked like us, you know?

Looking back, at the time, it was perfectly normal. You just sort of read these amazing books by literary greats. But I have to say that now that I'm a bit more woke, [laughs] I have to say that I sort of wish that, at least in the early days, there was a bit more diversity.

What my mother was very good at is, where we saw a lot of diversity, was in this sort of images of Black success, you know, those cutouts of Nigerians or Ghanaians who are poets and who are writers and who are novelists and seeing articles about them on the wall. She was excellent at that.

But I think that now my favorite author in the entire world is Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who's another, obviously, Nigerian author who has written Half of a Yellow Sun, Americanah, and various other books. But I love her because, when you come from a part of the world that is not considered the center and you find a great novelist who's able to tell stories that are about you and your culture, you cannot put a price tag on that.

I feel as though when I read her words, wow, my voice, my story, where I come from, that actually matters, you know, that has meaning in this world. And when I think about Rudyard Kipling, I mean, those guys are great, they're wonderful, but they don't necessarily reflect my story.

KO: I want to hear about the experience of narrating your own memoir. You know, your brother does have a couple of wonderful performances on Audible as well. Did he give you any tips? And what was it like reliving your story in that medium?

ZA: I had no idea about the length of time it takes to record an audiobook. They had blocked off about four days, and I thought to myself, "My goodness, it can't take four days to record an audiobook.” But lo and behold, it did actually take four days of me going to the studio and speaking. Obviously, you know, you have water, you have breaks where you can get up and walk around and there's a lunch break. But by and large, you are speaking into a microphone for about eight to nine hours a day.

And luckily for my job as a news anchor, I do have to talk. It's only for an hour at a time, though. I've never experienced anything close to [eight or nine hours]. And also it requires so much emotional and mental energy. I mean, obviously, it's sort of like acting. You're performing because there's dialogue that you have to act out, which, I'm not an actress. I might be related to [an actor], but I'm not an actress myself.

"Everybody has a tape that plays in their head about what they can and can't achieve. The greatest thing that my mother did for me was change that tape."

I think, though, for me, the most painful part of it was reading Chapter 1. I started reading Chapter 1, which is all about my father passing away, and for a minute, I kind of regretted being the narrator. I thought to myself, “Maybe it would've been a better idea to hire an actress to do this because it is so painful having to relive.”

And also, every single time you stutter or you stumble—and for me, there were plenty of times I did that in Chapter 1, because it was just so painful—you have to say the line again and again and again and again. And so you're repeating the line about your father being killed in a car crash again and again and again. And it is just, it is like a knife in your heart every single time. So, I definitely enjoyed the later chapters, narrating that once I got into the groove, but the first two chapters were quite difficult.

KO: I'm sorry that you had to relive that over and over as you were going through the recording process. But I am selfishly grateful that you did not hire an actress, because your performance is beautiful and so moving. And you could just tell how deeply you felt in those moments, but then also the wonderful moments of hope and resilience and the great affection that you have for your mother and your family. So I loved that you were the voice behind this as well.

So, there are these huge defining moments that can split a person's life into before and after. And the loss of your father when you were just five years old is definitely one of those moments. And you did lose him so young, but clearly he still looms so large in your life. And I'm curious, what would you say is the biggest lesson that you still carry from him?

ZA: I would say my father was an exuberant human being. My mother always says that anytime he left the room, it felt as though 10 people had just walked out. He had that kind of personality. And he was always, always willing to help other people. He was the most thoughtful person, you know?

My uncle, my mom's brother, said to me—I asked my uncle, “What was my dad like as a person?” And he said, "Everything that I have tried to achieve as a man, my whole identity as a man, in terms of what I'm striving to achieve and, you know, the type of man I'm striving to be, is 100% modeled after your dad." Which is an incredibly deep compliment, you know? And when he said that, that's when I realized, "Gosh, this guy was a very special person.”

He also didn't really do just one thing. I mean, he was a trainee doctor when he passed away, but in his heart, he was a dancer. He was somebody who loved music. He was somebody who, I think if my dad was more honest with himself, he probably would've just been a full-time musician. But he had chosen medicine because that is what his community back home expected of him. I mean, he was a Nigerian immigrant who had left to go to England after a civil war had devastated his community in Nigeria.

And so the expectation was that, “Okay, you’re gonna be able to go to England, that’s fine, but you of course have to provide and send money back to your family back in Nigeria.” So the most obvious, sensible thing to do was to become a doctor or a lawyer. And so he chose medicine.

But I think the other lesson, I would say, about my dad, something that I have learned from in terms of a mistake that he made, I guess, is that you do only have one life. And therefore it is important to do what you're passionate about. It is important to live out your dreams and to make sure that you fulfill the highest, most joyful expression of yourself. And my dad didn't do that because he felt obligated to his family back home, which is of course a noble thing to do, something that probably didn't make him that happy.

And so I think the lesson is, and I think this is why when eventually when my mother sort of figured out that my brother wanted to act, I think she'd realized that my dad had spent his whole life—he died when he was 39 years old—spent his entire life working toward becoming a doctor. And he didn't even become a doctor. He lost his life before he even, before he even achieved something that wasn't even his dream. You know what I mean?

And so I think the lesson is you only have one life and just do what you really care about. And that's the lesson I've taken from it too.

KO: I think it's a great lesson for all of us to take away from this memoir. Is there anything else that you hope listeners gain from experiencing Where the Children Take Us?

ZA: Well, I think a lot of people ask me about the whole parenting thing. I talk about some of the unique ways that my mom parented us, but I really emphasize that I don't want this memoir to be prescriptive in any way. I'm not here to tell anyone how to raise their kid.

I think a lesson that has resonated with a lot of people is the eight-hour rule. It's something that my mother came up with and this idea that, you know, she said to us, at one point, she wanted us to divide our day into three equal parts. So obviously there's 24 hours a day. She'd make us divide it into eight hours each and she'd say, "Okay, the first eight hours should be spent sleeping. The second eight hours should be spent at school. And the last eight hours of your day should always be spent working toward your dreams."

And that is really powerful, you know? Because it was a beautiful lesson about how you use your time. Because her whole theory was that, listen, everybody generally sleeps for eight hours. Everybody, generally, they only have one job, generally goes to work for eight hours. So the only real way to distinguish yourself from everyone else and to set yourself apart is in how you use the last eight hours of your day.

So my mother went to these kinds of somewhat extreme methods, you know? In order to help keep us focused. But my mother was in a very, very difficult situation. She was raising three kids. Was pregnant with her fourth child when her husband was killed in a car accident. She had to travel to Nigeria without necessarily knowing whether she was going to be burying her husband or her son. You know, my dad was the love of her life. Literally the only man she'd ever really known. And she suddenly had to raise three, then four kids in a foreign country by herself.

So she went through a desperate situation. And so she resorted to, quite frankly, desperate measures. I don't necessarily know if I think that everybody needs to go to those sorts of lengths. And people sort of read this and they highlight parts of the book and they're like, “Okay, I'm going to do this with my children. I'm going to do that. I'm going to do that.”

And I think people should just take from it what they want to take from it, but it's not prescriptive. It’s sort of just me wanting to share with the world my experience, and my intention in writing this is really to celebrate my mother.

KO: Well said. I have three young boys. I definitely was tempted to whip out my own highlighter in moments, although I was listening, so it was more of the bookmarking experience. But I understand. She’s remarkable.

So, what's next for you?

ZA: Well, I have a wonderful job here at CNN that I love. I've been at CNN for nine years now. And I'm really happy here. Will there be another book? I'm not sure yet. I'll just see where life takes me. I'm lucky in that I've achieved two major dreams that I've had for a while. One to work at CNN, and I have my own show now. And number two, to write a book. And so I've done both of those things.

KO: And I think living out both your parents’ highest expectations for you, which is that you get to live out your dreams.

ZA: Mm-hmm.

KO: So congratulations on that. And congratulations on this memoir.

ZA: Oh, thank you so much. Thank you so much, Katie.

KO: Listeners, you can get Where the Children Take Us by Zain Asher right now on Audible.