Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

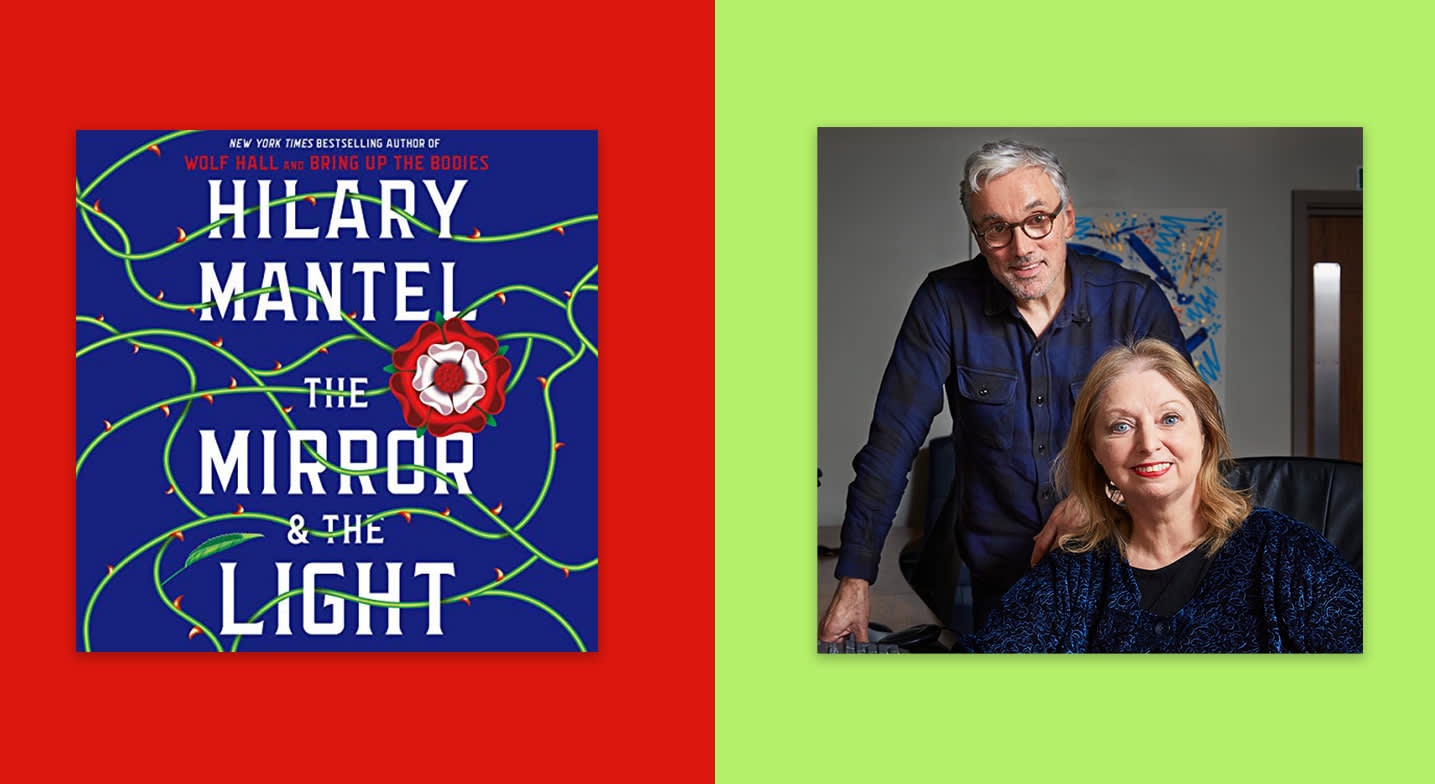

Christina Harcar: Hello. I'm Christina Harcar, the history editor at Audible.com, and I have the great pleasure today to be on the phone with Hilary Mantel, OBE, Booker prize winner twice over, best-selling author of a dozen books, and the creator of a trilogy of works about Thomas Cromwell — Wolf Hall, Bring Up the Bodies, and The Mirror and the Light.

Hilary Mantel is my favorite contemporary author, and today we're here to talk about The Mirror and the Light. So, welcome. Welcome to Audible Studios by phone.

Hilary Mantel: Thank you, Christina.

CH: So my first question is, The Mirror and the Light picks up right where Bring Up the Bodies left off, at Anne Boleyn's execution. What is Cromwell's state of mind in the beginning part of this story, as the book opens?

HM: It's terrific tension. When Anne goes to execution, she's looking over her shoulder and right at the last minute she's expecting a messenger to come in from the King and say, "Stop. There's been a terrible mistake." And that doesn't happen, but Cromwell is equally tense. He's got everything settled but one never quite knows. He really needs that lady's head to fall. When it does happen, thanks to the Calais executioner and his very sharp sword, it's so swift that the spectators don't know what they're seeing. Is she really dead? And then there's the corpse as evidence.

But for Cromwell, problems are just beginning. He knows Anne's dead but he has this terrible feeling she's going to stick her head back on and chase him down Whitehall, and try, somehow, to destroy him, because he knows that in order to bring down the Boleyns, he's entered a set of very dodgy alliances. And all the people who’ve allied with him are going to want to be paid back, and this is the problem he's going to have to solve over months, even years. And, it's not over. So as soon as it's literally over and her head is in the dust, he knows, now trouble is just beginning.

CH: Ben Miles manages to convey all of that tension and all of the feelings that follow throughout the book, through his voice and his performance. And I know that he was handpicked by you. So this is a particularly exciting time for our listeners to encounter the trilogy in audio.

HM: Ben Miles emailed me this morning in fact, and said, "Do you realize it's seven years since we've known each other now?" And that has been an insight, this span of time in which I've been concentrating on The Mirror and the Light. And Ben and I met in the rehearsal room when he had been cast as Thomas Cromwell in the stage play mounted by the Royal Shakespeare Company. There were two plays, Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, or, as they went on on Broadway, Wolf Hall One and Wolf Hall Two.

And I didn't have any part in casting Ben. When we began I suppose it was a little awkward because I was not the official adapter, and I didn't know what my place was in the rehearsal room, and I had to feel my way. It was like going back to being the beginner. And caught between two, because it's really good to refresh your practice every few years, and come into something where, actually, you don't know where you're putting your feet. You have to learn all sorts of new dances and I felt like a complete beginner in a dramatic process.

My task was to make the voices speak as I evolved them, and to keep my hand on the unruly energies of all those dead people. So, every day I had to wake up and show the dead who's boss. And I'm boss because I'm holding the pen now.

And as rehearsals went on and then the production was based at Stratford, then in London in the West End, then we came to Broadway, and Ben would ask me to step aside to feed him, as it were, with stories about Cromwell's early life — those things that never got on to the page — or just to tell me the content of his dreams. And that was all very understandable in a very creative process, to me, because it was helping me bring up the third book.

But of course, it wasn't very long before the process reversed itself rather literally. Ben started to tell me Cromwell's memories and his dreams based on what was going on head during performance. And slowly began this extraordinary process of communication, whereby Cromwell became a sort of joint creation. It was wonderful for me to watch Ben make him physically and to make him vocally. So, then when we came to the audio book of The Mirror and the Light, I thought, "He's obviously the go-to guy. If he would do it, then, this is the best I can give the listener, because that has become the voice of Thomas Cromwell." And behind the reading is all Ben's knowledge of the trilogy, but also of those things that we've discussed off the page. Actually, when we were in rehearsal at Stratford-upon-Avon, and I was sitting where the audience would be, and we had a coffee break, and we were in the dark, and I suddenly realized that Ben was sitting in the aisle next to me and speaking to me as Thomas Cromwell. And he said, "I'm a good dog. If you send me to guard something, I'll do it." And then he vanished. So, I just took those words and I put them straight into the book. I didn't think that they could be improved on.

CH: That is a wonderful anecdote.

HM: And so that was how the process worked. And what we're doing now is, we're trying our hand at writing the stage play of the third book together.

CH: Is it liberating for you to inhabit Thomas Cromwell as a Tudor, or because he's a man? What is the aspect of being Thomas Cromwell on the page that opens so miraculously that transference where we're all suddenly Thomas Cromwell? What is it, do you think?

HM: I think, generally, in the process of authorship, it's very freeing to be able to express the other gender as it resides inside you. You know, a male author’s got lots of women packed away inside him. The female author has got all these potential men enfolded in our imagination. And they are, I think, in a sense, part of our own personality. These are Hieronymus figures, to put it in Jungian terms. They have to stay quiet. You sometimes see a flash of them as other people, and you think, "Where did that come from? That's not your top surface personality." That's someone else speaking from inside.

But as an author you learn to do this consciously. You open the door and you let these people pour out into the street, and there is something absolutely liberating about that. Now, the Tudor male, of course, is not a modern male, and so you have to do two jobs, really. Get yourself back there into the mindset of the period and its culture, and get yourself into the mindset of a man of that time. But of course, when you're learning about the world of the 16th century, to be honest, you are usually seeing it from masculine eyes because it was they who held the pen and described their world. It was they who painted the pictures and wrote the music, by and large.

So as you explore the world of their culture, their religion, their philosophy. You are hearing men's voices all the time. What I think I always find very difficult is to get under the skin of a Tudor woman. I think it will be possible, I will certainly give it a go, but I think it will pose this terrific challenge.

CH: I wanted to thank you, not just as an author, but as a recommender. I have been reading and listening my way down the Hilary Mantel recommendation list and I have Darkness and Day next up in my queue because you’re an Ivy Compton-Burnett fan.

HM: Ivy Compton-Burnett is just incredibly important to me. She's my go-to person when I feel as if my spring's broken and I can't write because something in the way that tickles the speed of her prose corresponds to mine, and it's as if she sets me going again. And I only have to read half a page. I put the book down and I can do it again. She writes almost entirely in dialogue. If you haven't read her, I'm not sure that Darkness and Day would be my starting point.

CH: Ooh, well, what's a better starting point?

HM: I'd go for A Family and a Fortune, or A Heritage and Its History, or A God and His Gifts.

CH: Thank you. I will. Absolutely.

The tension of Thomas Cromwell and the idea that Anne Boleyn could rise again, you know, in our modern terms it's almost like the hand coming up out of Carrie's grave at the end of that horror film.

HM: Yes, exactly.

CH: So I guess my question is, do you feel that thread runs through all of your books? This idea that things are never quite put down?

HM: I think it does, and the idea of a cycle whereby what you have done or what you wouldn't even imagine comes back to bite you — or maybe comes back to inspire you. Let's be cheerful.

CH: [Laughs]

HM: I'm fascinated by the way the things that happen in our lives work their way underground, lurk around in our unconscious mind, and then suddenly they break the surface, and not always in a sinister way. Sometimes in a really helpful way, and I guess that's the process of authorship, really. As you go through life you notice a thousand tiny details, and then, there they are, suddenly surfacing again. And you think the use of them and years later you say, "Now I grasp what that was about," and you put it into a story.

And, although I didn't know it at the time, I think I was forecasting my process as it would be doing the trilogy, because having absorbed all the research and all the background material, it's then necessary to listen to it, to create a space for it to become an object in its own right, to go through the creative process of modeling a new work out of everything that other people have created in the far past. And I think my own character is teaching me how to go about this.

And Allison's problem is that the dead all talk at once. And, sometimes, they are more powerful than she is. Now, my task was to make the voices speak as I evolved them, and to keep my hand on the unruly energies of all those dead people. So, every day I had to wake up and show the dead who's boss. And I'm boss because I'm holding the pen now. But, at the same time, I'm trying to give them their space and allow the book to happen.

It's paradoxical, because on the one hand, you have a process of very tight authorial control, and on the other hand, you used the word freedom earlier, and that's what you're trying to do: turn the characters loose so they're not hampered by knowing their own story. You know their story. They don't. They're speaking and they haven't got a script. That's a wonderful thing.

CH: Would you share with us who or what, do you believe, is the true love of Cromwell's life?

HM: It's a really interesting question because the historical records give us very little access into that private part of his life, and what I set up in my books is, what starts off as a kind of running joke as to whether he will ever remarry after the death of his wife. But then, the rumor pervades England that he is remaining unmarried so that he can marry the king's daughter, Mary, and it was very dangerous to Cromwell. And the people around him, his boys, start to say, "Look, sir, the next woman you meet, just ask her to marry you. And if she's already got a husband, don't worry, we can get rid of him. Just go out into the street to find a bride. Just do anything to stop this rumor."

And gradually, as the book goes on, his tentative efforts toward possibly finding himself another wife take on an almost tragic tone. So, it's a joke that darkness darkens. And I suppose the other thing I could say is that for a man of his time not to remarry, especially if he had a young family, was really rare. Sometimes people remarried with what seems to us like indecent haste because it was a practical matter, and people thought, "I've got to have someone to bring up my children and run my household." And these may not have been exactly arranged marriages, but if there was an emotional connection, it tended to go after the marriage, rather than before.

HM: So, it's possible that his wife, Elizabeth, was the love of his life and that he didn't make that connection with any other woman after. He certainly had strong friendships with women, and that's one of the things you notice about him, the amount of his correspondence and the references to the women around him. But, of his love life, we know nothing. I think it's also possible that when you're a minister to Henry VIII, it's wives, wives, wives all day long.

CH: [Laughs]

HM: And maybe what you crave is an exacting masculine company at the end of the day.

CH: Courtship would be a busman's holiday.

HM: But if you look outside personal relationships and ask what’s the love of his life, the thing he was dedicated to was the English Bible. And, it was through his pushing and pushing Henry that the Bible in English was finally placed in each parish church. It's not so much a religious landmark. It's a landmark in the development of the English language, because this translation was largely the work of William Tyndale, and Tyndale's name wasn't on the Bible because Henry regarded him as a heretic. But it was his energy, his drive, his mastery of the English language that created this great work, and it's a sense of giving the language back to people. Whether they're literate or illiterate, they're going to hear these phrases.

And the Bible makes its way into their language, so that even today, quite unconsciously, we're often using phrases drawn from those early translations. So, if I have to choose, I'm going to say, his great love is the English language. This is a man who speaks several European languages but finally finds his home in the vernacular. And therefore, I think it's quite fitting that someone should quite humbly give some years of their life to writing about this man, and trying to do it in prose that has been fed by the prose of his time.

CH: Thank you so much for your answers today, for the monumental accomplishment that this trilogy is, for your time, and for the insight. Heartfelt thanks from all of us.

HM: Thank you very much.