Two households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Verona, where we set our scene,

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny,

Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.

From forth the fatal loins of these two foes

A pair of star-cross’d lovers take their life;

Whose misadventured piteous overthrows

Do with their death bury their parents’ strife.

So begins Romeo and Juliet, with Shakespeare making the unusual decision to summarise, in the space of eight lines of verse, the play to come. In the beautiful but hot-tempered city of Verona, two warring families renew hostilities. Their unfortunate offspring become lovers and kill themselves. With their deaths, the vendetta between the two houses ends.

Violence, ancient hatred, hot-blooded teenagers, doomed illicit passion, and redemptive suicide … ingredients enough for a tale that has become probably the most famous romantic tragedy in the world. But while the most familiar telling of it may belong to Shakespeare, the story certainly doesn’t.

The first recorded version of what was to become Romeo and Juliet appeared in a collection of Italian romances published in 1476. It was then set in Siena and the lovers were called “Mariotto” and “Gianozza.” The names of “Giulietta” and “Romeo” did not appear until an adaptation by a Venetian writer in 1531.

This was elaborated upon further by a later Italian author, Matteo Bandello, as part of a story collection which may also have inspired Shakespeare’s Much Ado About Nothing and Twelfth Night, as well as John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi. In 1562, Bandello’s work was translated into French. That version was turned into an English poem, by a little-known writer called Arthur Brooke, which Shakespeare used as the basis for his play.

While there are countless conspiracy theories surrounding Shakespeare — that he was someone else, or even Italian himself — we know one thing for sure: He was certainly an avaricious devourer of the work of others. At most, only four of his dramas — Love’s Labour’s Lost, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Merry Wives of Windsor, and The Tempest — are thought to be original. The remaining thirty-three surviving works all pillage earlier histories, books, and even plays performed just a few years before.

Today we’d think of this as plagiarism, but in the sixteenth century there was no concept of copyright. Stories were deemed by many as free to be used and reused at will, and Shakespeare did that enthusiastically. Some 4,144 out of 6,033 lines in Parts I, II, and III of Henry VI are either copied directly or paraphrased from the work of others.

A fellow writer of the time, Robert Greene, wrote a harsh criticism of Shakespeare which grumbled, “there is an upstart Crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tiger’s heart wrapped in a Player’s hide, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of you.” Shakespeare, being a mere actor, was being presumptuous to think he could write at all — and beautified himself with the feathers of others.

Greene is a forgotten footnote in Elizabethan dramatic history. What he failed to appreciate was that Shakespeare’s genius lay in adapting raw and sometimes fairly poor material — Brooke’s poem falling into the latter category — and turning it into drama that struck a nerve with audiences everywhere and continues to do so to this day.

It’s hard to believe that Shakespeare was anything but an Englishman through and through. Yes, he extensively read a broad range of material about Italy, from fiction to history and political works, and loved to put that knowledge to good use. Sometimes, perhaps he tried a little too hard. In Henry VI, Part III he has Duke of Gloucester, the future Richard III, boast that his villainy will “set the murderous Machiavel to school.”

And Richard is certainly a Machiavellian character — not that he would have used the term himself; he was slaughtered at Bosworth Field in August 1485, when Machiavelli was just sixteen. A printed version of his seminal work The Prince didn’t appear until 1532, five years after Machiavelli’s death.

For Shakespeare’s generation, Italy, the home of what we now call the Renaissance, was the place all of Europe turned to for inspiration, with Italian books finding an easy route to translation across the continent. In a way, culturally rich cities like Florence and Venice were the Hollywood of their time, and a playwright looking to reach a mass audience — as Shakespeare was — would have known they were good places to seek ideas.

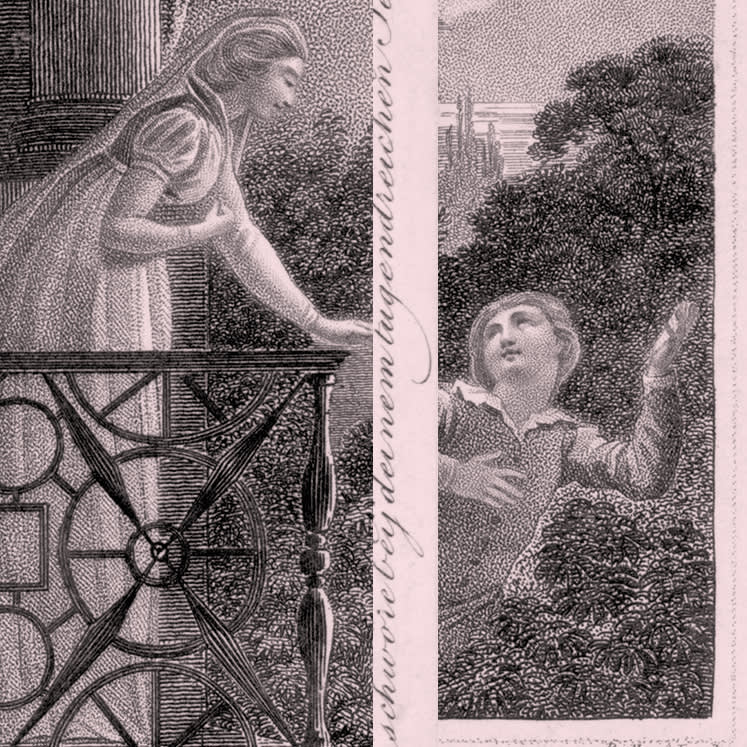

Shakespeare certainly read widely, but nothing in Romeo and Juliet suggests he knew Verona personally. The play displays no knowledge of the city’s long history, nor its geography set by the Adige beneath the Alps, nor its cultural roots.

Does it matter? Not at all. Even when the lovers were still called “Mariotto” and “Gianozza,” the idea was scarcely original. Much of the inspiration came from a far more ancient story about star-cross’d lovers — Ovid’s Pyramus and Thisbe. And Ovid himself was recording a fable that predated him, going back to the fifth-century B.C. historian Ctesias.

From ancient Athens to ballet and opera, countless paintings, musicals like West Side Story, and cinematic versions that range from modern Los Angeles to anime and cartoons, the tragedy of young love destroyed by a cruel and unfeeling adult world resonates down the centuries.

Perhaps one reason it has proved so universal is that it stems not from any single source but from the common historical pool of shared human existence, a world in which love and hate live hand in hand with hope and terror. The magic of Shakespeare is that he takes that simple yet supreme premise and turns it into a kind of trick mirror, one that reflects back something different every time you look at it.

This is why there can never be a definitive version of Romeo and Juliet, only the next in a very long line that stretches from the past to the kind of boundless future that Juliet envisions here.