Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

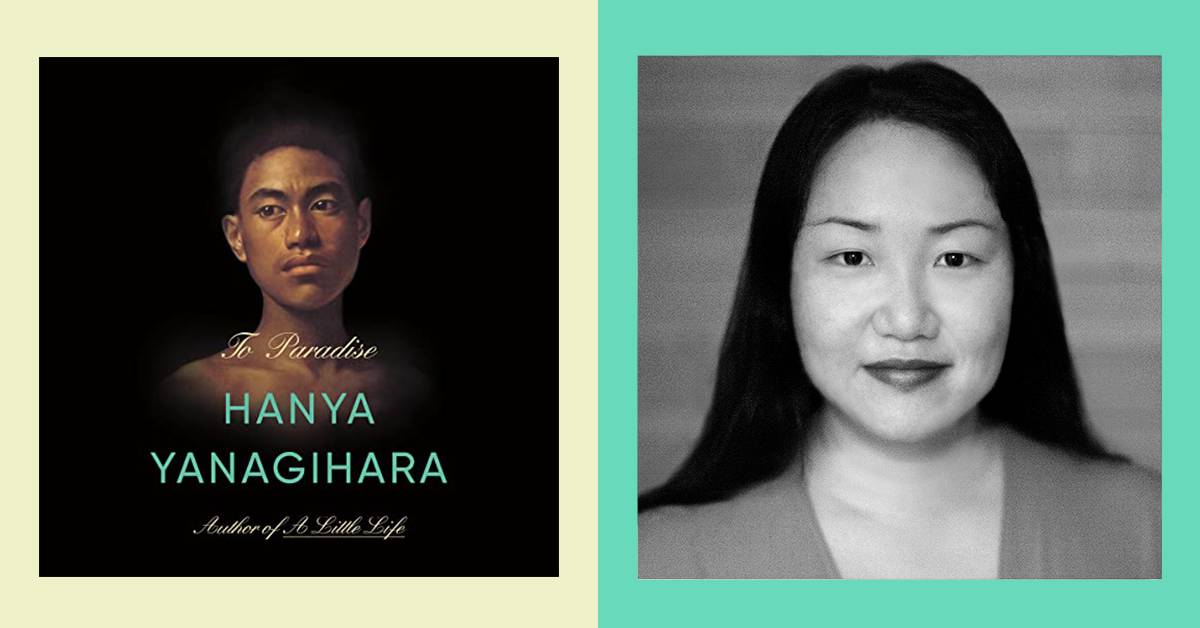

Jerry Portwood: Hi, I'm Jerry Portwood, an editor with Audible, and it's my pleasure to chat with author Hanya Yanagihara about her highly anticipated new novel, To Paradise, which is quite a departure from her last breakout hit, A Little Life, which novelist Garth Greenwell declared the "most ambitious chronicle of the social and emotional lives of gay men to have emerged for many years."

The new novel also mostly centers around gay men in surprising ways. In To Paradise, Yanagihara crafts an alternative history in three different narratives set in three different centuries, spanning from New York to Hawaii and back again. The impressive storytelling tackles big themes—equality, bigotry, migration, loneliness, love, death—as well as a soul-crushing pandemic. It's a challenging epic that has provoked many questions already. So thank you for joining me, Hanya.

Hanya Yanagihara: Thank you so much for having me, Jerry.

JP: I wanted to start at the beginning and fans of A Little Life may be surprised at what a departure To Paradise is. Some may even see it as three books yoked together by this idea of all the action taking place around the same Washington Square townhouse in New York City. The first section, which is set in 1893, is it meant as a queer retelling of Henry James's novel Washington Square?

HY: Yes and no. I'd always loved the book and I'd always wanted to write a marriage story, which has been a dominant genre across many different novelistic cultures since the 17th century. The difficulty for this passage, the European marriage novel, was always about how women's ambitions and realities were going to be naturally circumscribed by how much money they had, by how much money they came from, or how much money they could marry into.

And I thought, what if there could be this marriage story that wasn't gendered? And then I started thinking, what if America was not founded on the bedrock of puritanism, but on something else. What would naturally shift? What would naturally shift is that you would have a different definition of what a relationship was, but you'd also have a different definition of what a woman could and couldn't do. On the other hand, as readers or listeners will hear in this part of the book, it doesn't mean that the citizens of the Free States, which is the country that I invented within America, are welcoming of Black people or of Native Americans or of Jewish people.

"What if America was not founded on the bedrock of puritanism, but on something else. What would naturally shift?"

It's not supposed to be a paradise for everyone, but it is a different reconsideration of what America might be had it not had one of its fundamental founding philosophies.

JP: What's fascinating about this history for me is that even though same-sex love and marriage is the norm, all the Native Americans have been exterminated, Black people aren't allowed to have equal rights, and Jewish people as well. Do you think it's possible to have a nation that is not tainted by some shame or sin or cruelty?

HY: No, of course not. No nation is perfect and no nation can be perfect. Every nation that defines itself as a paradise is bound to be disappointed in a way. The original meaning of a paradise is a walled garden. There is not going to ever be a society or a nation or any sort of community that is not in some way exclusive. This book certainly doesn't suggest otherwise.

JP: In all of these instances of what you describe in the book, there are failed utopias. In the first one, our first David—I should note that there's many Davids and many Edwards and many Charleses and other people named similar things—he wants to escape, even though he has many privileges and he risks his life to do so. I was really interested in how all of the characters are involved in these migrations, and they never seem to bring true happiness.

And I was thinking again about that idea of To Paradise, the title and also a refrain that's at the end of each of the sections, and it seems to be understanding “paradise” the way you just mentioned: that you really can't appreciate it until we've lost it.

HY: I think you're right. It also plays with this idea of paradise being to the west. From the beginnings of its history, Americans were always looking towards the West as if there might be something better beyond the next horizon. And of course, what happens to this book is you go all the way west until you hit the end of land and then you go to Hawaii. And even when you're there, there is no finding of this better other place. And by the third book, Hawaii itself is no longer a viable option. Paradise itself has been extinguished in some way.

JP: I was actually lucky during our reprieve, [when] we felt like we could travel this past fall, that I visited friends who live in Honolulu. I love the section about Hawaii, and I was curious with that background, bringing that alternate history of Hawaii as well into this. It seems like a very personal moment.

HY: The second part of the book is our America, so it's a recognizable America, pretty close to what we understand and accept as American history. The second part of the second section of the book is about a man in contemporary-day Hawaii who tried to reinvent a prelapsarian Hawaiian kingdom where he would be king and where colonization and the encroachment of the West had never happened. If you've grown up in Hawaii or visited there, it was of course a kingdom.

JP: For people who might not know some of this other history, you attended Punahou in Honolulu, where so many distinguished people graduated such as President Obama and Sun Yat-sen, and it was founded by Hiram Bingham, which is a surname that appears throughout the book. I assume that is the connection you were making?

HY: Yes. Depending on the kind of America you grew up in, you will see and hear different references in this book that other people won't. So, as you said, Jerry, if you are from Hawaii, you'll know that all of the names of the main characters—Bingham, Bishop, Griffith, Cook—are the names of American missionaries who came to the kingdom of Hawaii in the 19th century.

Many of them married into the Hawaiian royal family and became very wealthy. And if you are versed in more-modern American history, of course you'll understand that the relocation centers and the third section of the book where the government sends the sick are actually the names of Japanese American internment camps, where 120,000 Japanese Americans were sent after the Pearl Harbor bombing, because they were considered enemies of the state.

At various points since, the government has talked about using those camps to house other groups of citizens. At the beginning of the AIDS epidemic in New York City in the early '80s, if any of you have read or listened to David France's book How to Survive a Plague, there was talk about sending gay men to camps, not necessarily these Japanese American internment camps, but camps in the inner part of the country. And of course around the Muslim ban, there was talk about sending Muslim citizens to camps as well.

So this idea of imprisoning Americans on a mass scale is something that's resonated throughout our modern history as well. On the other hand, if you don't grow up in one of those Americas, or if you are not American at all, I hope that the narrative is equally satisfying. You just might be aware that something lives right beneath the surface that you're not quite getting, but you feel that you perhaps should.

JP: Yeah, it was actually the 1993 section that personally resonated with me very deeply, just because I came out as a gay guy in 1992. It was a weird time, and I grew up with that shadow of AIDS... [You're] someone who did come from a great education in Hawaii and then came to the Northeast and probably felt othered and had to deal with racism and things like that, is that how you access that sort of feeling of being this outsider or not fitting into this milieu?

HY: Yes and no. In that section that you're referring to, the first section of part two of the book unfolds over a single night, and as you said, there's an illness that is devouring gay men in the city. And of course it's AIDS, although AIDS is never named. In this sense, this dinner party that this group of friends is having is a walled garden in and of itself.

It's a place where they can gather and they can be open and they can be honest. And outside of this house is a place where some of them face danger or death or dismissal. I think that one of the great differences between the last great pandemic, which was of course AIDS, and COVID is that people forget how much stigma there was towards the affected and how institutions, the government, society, churches, citizens turned their backs on those early sufferers. It was really the community of gay men and lesbians themselves who had to take care of their own and advocate for themselves in a way that no group of people should have to do single-handedly. But they did.

So that part of the book is also a tribute to that time and to this idea that a paradise can often be a community. On the other hand, no community should have to do this much for themselves. And of course, we've seen that sensation repeat itself with various different kinds of communities in not just America over the successive decades.

JP: I read a quote where you said you agree that a non-gay person should not be representing queer life, and I thought that was great that you were able to access this. I don't know if you identify as queer, as somebody who's an outsider or misfit, but how do you give yourself permission to be able to invest so much in excavating these stories that some might say you're not allowed to do?

HY: Well, I had been invited to be in a debate at the Oxford Union, and the idea was that a non-queer writer should not be writing a book that becomes emblematic or representative of the queer community. And they wanted me to take the "con" side of that, and I didn't agree. I don't think that a non-queer writer should be able to become the representative voice of a community.

Having said that, I think that there is no single representation of any community. If I write something from the perspective of an Asian woman, I have no more or less validity or legitimacy than anybody who's writing from that perspective—including people who belong to those communities. I think that a fiction writer has to be able to write about whatever she wants and whoever she wants, but she has to make sure that the characters that she creates move beyond tropes and clichés, and that they exist because they're full people and not because they're supposed to be symbols or icons of a certain imagined community, and even that she has to think that there is no "single community." There are identities, and within identities there are many different ways of how people feel about themselves and identify themselves and name themselves and think of themselves.

A writer cannot be constrained to writing only characters who superficially or tribally resemble themselves. The world is full of different kinds of people and a writer should be able to reflect them all, but with the responsibility that all writers have to create nuanced and interesting and complex and, sometimes, maddening characters.

JP: I was curious if you have a relationship to audiobooks or what you feel about them.

HY: I think it is a form of reading. I have an acquaintance who uses a wheelchair and she says, "I'm going out for a walk," and I really love that because it does take the idea of the verb to walk and it expands the definition of what that means. In the same way, even though I myself am not an audiobook listener, I do think that audiobooks are completely reading; it just expands our idea of what reading is.

I love reading plays. I know it's not the same as seeing a play, but I think the difference between reading a book and listening to a book still lies within the absorption of the language, rather than your actual eyes on the page.

JP: There are some incredibly talented people. Edoardo Ballerini some consider, like, the god of audio narration. There's Kurt Kanazawa, Catherine Ho, and B.D. Wong and others. Were you involved at all in the choices or was that something that other people presented? How did that work?

HY: I was, and it was great going back and forth because I really wanted either a native Hawaiian actor, or I wanted an Asian actor who was conversant in Hawaiian or at least understood how the Hawaiian language should sound. So we went back and forth a few times.

For Charlie—who's the third part of the book—I wanted an actor who sounded around the right age, so late 20s, early 30s, and could project a kind of affectlessness, but that didn't sound too showy and didn't sound too robotic, that you could tell that there was a human beneath this person who was having a difficult time naming her own emotions. And then for the part that B.D. reads in the third part of the book, this character ages from his 40s to his late 70s, his 80s, actually, and I wanted someone whose voice begins the book with a lot more attitude than he ends it. He becomes a different person over the course of the book, and I wanted someone who could project a kind of sorrow as the book continues and as he learns lessons that he never thought he would have to learn and as he rethinks his perspective in many ways. That's a tall order for an actor. I had heard other things narrated by B.D.; I knew he could do it. He's such a great actor and a great reader, but these are not easy skills.

These are actors who have to use their voice to convey so much tone and who can really augment the narrative by how they can control their voice and their reading and their performance. As an author, you're really listening for the people who understand how to do that intuitively I think.

JP: I was checking out your Instagram and the book's Instagram, and you worked with an artist to create this really great box for the book galley early on. And I happened to be walking through Washington Square last night, my nephew was visiting and as I was showing him, I got so excited about the townhouse, there's so much about that. I started thinking, wouldn't it be great if fans of the book started wanting to visit the places mentioned the way they were coming for Sex and the City tours? Do you think that that could happen? I mean, people flocking to Washington Square?

HY: That would be great. It's currently owned by NYU and it's faculty housing, I believe for their members of their School of Social Work. One of the fun parts of creating these three worlds all set in New York was exploring parts of New York that I knew, inventing other parts and also finding areas that I wasn't familiar with at all.

I think one of those places that most New Yorkers are probably not aware exists is Rockefeller University, a postgraduate university on the Upper East Side of Manhattan next to Memorial Sloan Kettering, the cancer institute that specializes in biological sciences. It's a beautiful campus in the low 60s in York, and it has Manhattan's only freestanding mansion on the grounds of that campus. It has a spectacular art collection, obviously from the Rockefellers, of contemporary and modern art. It's one of those things that I think very few people know about, and it is one of the centers of action for the third part of this novel.

"One of the fun parts of creating these three worlds all set in New York was exploring parts of New York that I knew, inventing other parts and also finding areas that I wasn't familiar with at all."

JP: You also focus a lot on Roosevelt Island, which is a place that even though we might know about, very few people seem to want to visit. So you had that connection as well.

I wanted to talk about Charlie. As you mentioned, she's one of the characters in the third book, which is set in 2093, and I think she's one of your only female protagonists to date. Is that right?

HY: She's the only major female protagonist.

JP: She definitely feels to be neurodivergent. And, actually, then I started thinking, many of the characters in some ways do seem to be grappling with mental health or being somehow outside of "normal." She is this sort of outsider in a strange land. I found her fascinating. As you mentioned, you didn't want her to come across as too robotic, but also the way she describes and engages with the world around her is fascinating. Can you explain a little bit about developing her as a character?

HY: Her voice came very easily, and I definitely don't want people to try to diagnose her. I'd originally thought, should I have a section in which she was actually named? Her caretaker is her grandfather who's a scientist, and so he understands naming all sorts of conditions, and he never does name what's wrong with her. I thought that was a really beautiful gesture in a way towards her because he understands that she's a complex and complicated and often mysterious person to him, and that in a way by trying to give her some sort of label, some sort of malady, some sort of condition, it would be reducing her to that condition, and so he never does.

And I hope the readers don't either. But yes, all of the protagonists in all three sections of the book, as you say, Jerry, are somehow removed, they somehow feel as if the world knows something that they can't quite figure out, or that society has moved on and left them behind somehow. I think many of us feel like that to different extents, but I think that for these characters, it is more severe.

It is something that has hampered their ability or their confidence to feel that they're a part of—not just their city or their society or their country—but their family. And all of them want to be loved and to find love, and that is something that I think every human wants; it's just that not every human knows how to express that.

JP: The final part is about a series of pandemics, and we're still living during one. It's hard to escape some of the feelings of loneliness and needing this sort of partnership and having connection. There was this great quote about it being a "pretty fiction" that we told ourselves when we were younger, that our friends were our family and were as good as our spouses and children, but that was a lie.

I feel very much for my friends and I have several that I had to make sure that I was checking on and making sure that they weren't feeling overly lonely, and knowing that I can't fix everything for them. But tell me a little bit about that, because obviously you were finishing this book, I think, during the pandemic and so some of that must have seeped in.

HY: Yes. I think a lot of people felt betrayed that the people that they assumed would be with them in a very dark time had chosen instead to remain with their family or the people they lived with. And I think even people who would've assumed that they would've been in that category did otherwise, and welcomed people into their houses and made room for strays as it were, and found themselves gravitating more towards their friends or created families.

I think 2020 was really a test of who people truly were for all of us, and what we would truly do in an emergency, because it did feel like an emergency.

JP: So I mentioned that listening to this book was extremely rewarding for me personally. I can't imagine not having experienced the stories without this narrated version because these talented people really impressed me, but especially I think it's because so much of it is told through letters and emails. I was curious if you wanted to write this sort of hybrid epistolary novel from the beginning, or if it's just the way it made sense.

HY: I love epistolary novels and it's a very flexible form. It's an old form of a novel, and it has a lot of resonance today. I'm of the generation where email really became widespread, and that is how I mostly communicated through my early 20s. It was cheaper than making a phone call, and so you would write long, long emails to people. That's gone away a lot.

But I did like this very romantic form of communication, which is still a way I communicate today with people who are close to me. It is still the way I most enjoy communicating. I think people who like writing letters somehow always gravitate towards other people who like writing letters. In the days of the pandemic, it felt like a treat to get mail or to get a long email or to have something to enjoy on your own time.

I wanted to keep that sense of romance and mystery and intimacy that only letter writing can really provide in the sections of this book as well.

JP: I think that you may have just revealed this: that you're a classic romantic. I often get criticized that I'm very pragmatic and so I'm not romantic, and yet I think I secretly am more romantic than the people who get gushy. Am I overreaching?

HY: No, I think I'm very romantic and I think all writers are.

JP: I could actually talk to you all day and ask lots of other really nerdy questions because I have lots of other things that I'm still trying to flesh out in my mind about some of the complicated, ethical, and other questions that come up in the book, but I'm not going to belabor it too much. So I just wanted to thank you for joining us and talking to us. It's been such a pleasure.

HY: Jerry, thank you so much. And thank you for your questions. I really want to thank the listeners for all their support for my work.

JP: And just so listeners know, you can get To Paradise and Hanya Yanagihara's other books on Audible now. Thanks, Hanya.