Note: Text has been edited and does not match audio exactly.

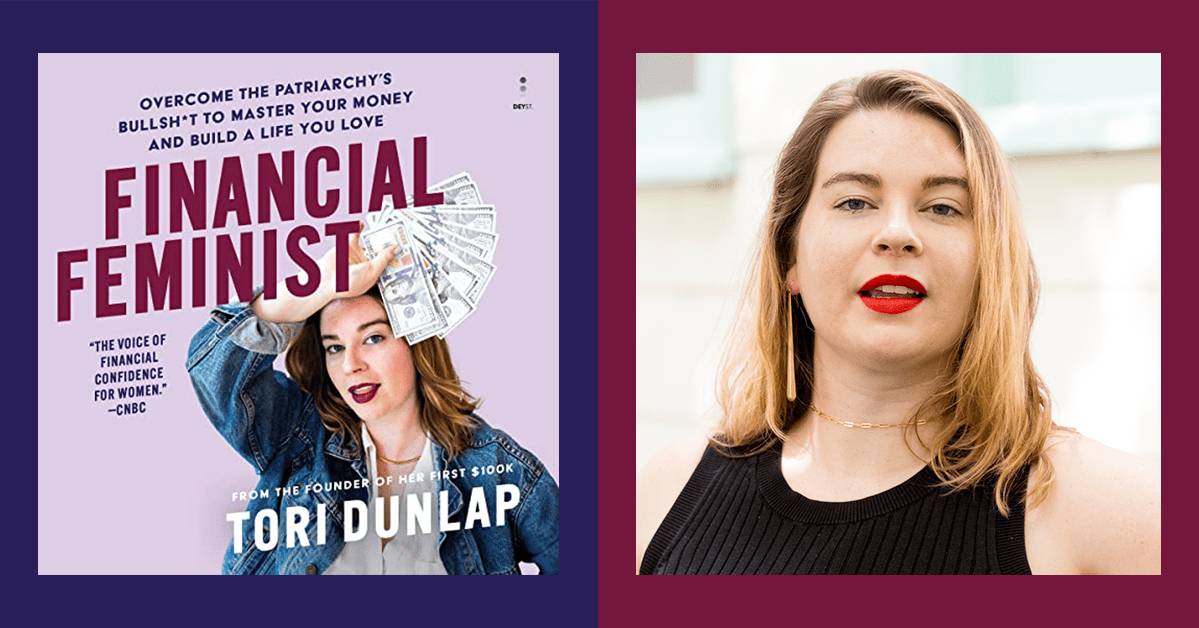

Rachael Xerri: Hello, I'm Audible's well-being and business editor Rachel Xerri, and today I'm talking to personal finance expert and fellow feminist Tori Dunlap about her audiobook, Financial Feminist. Welcome, Tori.

Tori Dunlap: Thank you so much for having me. I'm so excited to be here.

RX: Thank you for being here. So firstly, what is a financial feminist?

TD: This is a great question and one that I've spent years trying to answer. The way we define financial feminist at Her First $100K is this idea of using money as a tool to put on your own oxygen mask first so that you can then help others. We both start the book and end the book with one of my favorite quotes, which is "When you have all you need, build a longer table, not a higher fence." And it's this idea that when you take care of yourself, when you have enough money to be in situations you want to be in rather than situations you're forced to be in, when you have enough money that life seems a little easier and that you have all of those choices to build the relationships and the career and the life that you want, then you get to use money as a tool and a resource to be able to change other people's lives and change your own communities.

And I really saw that with my own work. When I became financially stable, when I became financially educated, not only did all of the options open up to me, but I could start making an impact. I could start giving people jobs. I could start donating to causes I believed in. I could see actual change in my community. I could support businesses I wanted to see thrive. And so the whole mission of our company and the thesis of Financial Feminist is, “Okay, how do we get more money into more women's hands so they can not only change their own lives, but the entire world can start to change?”

RX: That's great. So, let's talk a bit about Her First $100K. You started Her First $100K after you saved $100,000 at age 25, and you used reaching that financial goal as an opportunity to leave your corporate job that just wasn't working for you. Can you share a little bit about how you were able to reach that financial goal?

TD: Yeah. So, the Her First $100K origin story, my Batman origin story, was $100K at 25. I was 25 years and three months when I reached the goal. The joke was, as long as I do it the day before I turn 26, it still counts. So, there were a couple pieces. One, I graduated college debt-free, and that was a combination of me working three jobs while on campus, getting a lot of merit scholarships, but also having parents who had saved diligently for me for college. So, it's a privilege. It's really important for me to acknowledge that I wouldn't have hit that $100K as quickly as I did if I had some sort of student debt.

The other parts were a lot of me being financially savvy at a young age because I learned about money from my parents, but also, I was obsessed with reading about personal finance and figuring out a budget that worked for me. So I started investing when I was 21 or 22. I was maxing out my Roth IRA every year. I was also negotiating my salary. Every time I would either come into a performance review, an annual review situation, or would discover I was being underpaid, it was time for me to negotiate, or negotiate a new job. So, I was negotiating every job I've ever held.

"If you don't have money, if you don't have the flexibility to save money, if you are living paycheck to paycheck, if you are a single mom working two jobs and still can't get by, your knowledge of how money works doesn't really help much because you don't have money in the first place."

I was also side hustling. The business that is Her First $100K started as a side hustle. I was working a 9 to 5 in marketing and then I was growing this business on the side. So, when I did make money in the business, anything that was additional after taxes and expenses—especially when there was nobody else, I was the only team member—I got to put that money into savings or into investments. And I think the final thing that I really try to teach people is I focused on value-based spending. One of the common questions people ask me when they hear that $100K at 25 story is they go, “Okay, but you didn't do anything fun. You ate oatmeal and you stayed at home and life was miserable.” And just the opposite. I traveled internationally, I went out to eat, I lived in a high-cost-of-living area. I live in Seattle. I lived alone in Seattle.

I think there's a way to balance your financial goals with spending on things that you love right now, and I really found that value-based spending and mindful spending was the answer, and I talk about that a lot in the book. We spend an entire chapter on this idea that you don't need to stop spending money, but you need to spend more intentionally about where you want that money to go and what brings you the most joy.

I think those were all of the kind of components of that $100K, and that was the impetus of not only the company but my own personal journey as an entrepreneur. I was able to quit my job that I didn't really want to work at anymore in order to be an entrepreneur full-time. I hit my $100K goal, I went to Italy to celebrate with my best friend, I got the call for Good Morning America to do an interview in a pub in England, came home, did the interview, and quit my job three weeks later. And now we are a community of three and a half million people and, obviously, this book and a podcast, and so it's just been crazy to think about that I'm now 28 and life is very, very different in many ways than it was three years ago.

RX: What an incredible journey you've had so far, and you've been helping so many women online through social media, through your workshops, through your podcast that you mentioned as well. So, what inspired you to write a book? What inspired you to write Financial Feminist?

TD: Many things. The original inspiration was honestly child Tori. I was that kid who brought a book to anything. I had my nose buried in any book I could get my hands on. It was so interesting, I was doing an interview talking about this journey as an author a couple weeks ago, and I was home for Thanksgiving and I was in my childhood bedroom doing this interview. And it's so crazy to imagine—I could almost see seven-year-old Tori in the corner with her nose in the book looking up and watching 28-year-old me give an interview about the book that I have now written because I literally wrote down—I was seven or eight, because this is me, I was precocious and I was ambitious and I wrote down a bucket list of things I wanted to do in my life, and I wrote down that I wanted to write a book.

And little did I know it would be about personal finance and about feminism and economic progress for women, but it was as much fulfilling a promise to myself as it was to make sure this information is as accessible as possible. And I think that's the other piece is we have seen the impact that our work has on people's lives, especially women's lives. We get messages now every five minutes from a woman somewhere: “I paid off my student loans,” “I negotiated 20 percent more in my salary,” “I have $1,000 in my savings account and I've never had this much money before.” And the thing that always comes, it's the financial win and then a comma, and then “and I feel so much more confident now.” And that is the feeling I want for every woman.

Something about writing a book, one, feels like the biggest professional accomplishment of my life. Writing this book was really hard. It was really, really hard, but also, I think, there's few things as accessible as a book. You have 80,000 words of, hopefully, really powerful, really transformational advice and guidance for $22 or for $14 or for free at your local library, and so for us, writing a book for Her First $100K as a company and both for me as an entrepreneur, it was a fulfilling of a commitment to younger me, but also the realization that a book was the natural next step for us to make this information even more accessible and to have more nuanced conversations. We started doing this with the podcast as well, which is also called Financial Feminist.

But it's this idea that you can't talk about personal finance without talking about systemic oppression. You cannot have those things siloed. They are inextricably linked and there's only so much discussion of systemic oppression that can be had in a 60-second TikTok, which is where our biggest audience is. So, with the podcast and now with the book, we wanted to go deeper in these conversations and talk specifically about how money affects women differently, about the sort of narratives that we've been made to believe about money and about wealth that have been perpetuated by patriarchal systems. And what do we do about that? What do we do about the narratives and the stories, and how do we use money again as a tool? So, I think it was definitely fulfilling a commitment to younger me, but also the beautiful opportunity to reach as many people as we can with this really life-changing information in a way that feels extremely accessible.

RX: Absolutely. So in your own words, what is financial literacy and why is it so important for women to have it, and maybe as a part two to this question, what are some of the barriers preventing women from having access to financial literacy?

TD: I would define financial literacy as just an understanding of how money works and the system that exists and how to navigate it. However, financial literacy is not the end-all, be-all solution. I think there's a fallacy of financial literacy that, “Oh, if we were just taught this in school or if we were just brought up learning about money, that everything would be solved.” Now, I think we'd definitely be better off as a society, but I can't speak for you, but I know when I took pre-calc in high school, I learned enough for the test to hopefully get an A and I don't remember anything else. And if I was a 15-year-old, 16-year-old learning about a Roth IRA, one, I don't care yet because it doesn't really impact me, and two, I'm going to learn enough for the test because I'm in an educational environment and I'm going to dump the information when I don't need it.

So, I think that financial literacy, defined traditionally, is this idea of taking a class, typically in high school or maybe college, about how money works. For me, financial literacy is not just how to budget or how to set up an investing account, but what sort of systemic barriers are in place that actually make financial literacy a moot point? If you don't have money, if you don't have the flexibility to save money, if you are living paycheck to paycheck, if you are a single mom working two jobs and still can't get by, your knowledge of how money works doesn't really help much because you don't have money in the first place. So, I would define financial literacy as, yes, the actionable information around paying off debt, saving money, learning how to invest, and this book has all of those things. But the first half of every single chapter in this book is what I call the patriarchal bullshit of it all, which is what are the sort of systems that have been upheld that bar women from having money? Again, what are these narratives? Like, talking about money as taboo, or the pursuit of wealth is morally wrong.

There's so many narratives that are perpetuated to keep women underpaid and overworked, and like I said before, you cannot talk about budgeting if you can't also acknowledge that racism, sexism, ableism, homophobia all exist in this financial equation. So what I would really love to see in terms of what financial literacy actually looks like is, yes, the actionable things that we get into in the book, but also the other things we get into in the book, which is that our system is made by and for cisgendered, straight, white men, and that anybody who is not in that demographic is going to have a harder time navigating said system.

RX: Well said. So, you've referred to Financial Feminist as a survival guide. What's different about your listen compared to typical financial advice for women, like say “stop drinking lattes” or “stop buying anything that brings you joy”?

TD: Oh man, how long do we have? Again, it shouldn't be novel, but the acknowledgement of systemic oppression is somehow new in personal finance, or relatively new. I'm not the first person to do it and hopefully I'm not the last, but I think that that's one major difference. Again, one of the narratives we discussed in the book is you are not working hard enough if you're not rich. To be rich, you just need to work hard. And, of course, that is a bootstraps narrative that's perpetuated since the dawn of white American society.

To your point about the lattes and the "frivolous spending," so much of our personal finance language is gendered without us realizing it, and I give the example in the book that if you Google something like “how to save money” that is relatively harmless, the advice is different for men than it is for women. For men, it is about building wealth. It is not about limiting; it is about expanding. It's about how to increase your salary, how to increase the amount of money coming in, how to invest in real estate and the stock market. And for women, it is deprive yourself. It's not “go earn more money or go make more money.” It is spend less money on things we deem as "frivolous"—manicures, a little latte, Dior purses. So that in and of itself is extremely gendered language: men, build; women, deprive.

But specifically, we are asking women to stop spending money on the very thing that we expect them to do in society, which is perform femininity in a certain way. You're not going to be able to see the video of this, but I'm showing up at this interview without makeup, I haven't done my hair in a while and the roots have grown out. I am not performing femininity in a certain way. So, the very thing we're shaming women for spending money on—manicures, makeup, waxing, fashion—is the very thing that then, if you show up at work without it, you get called tired. Or if I show up at a job interview without makeup, I'm deemed "unprofessional," and I'm putting this in air quotes. And if you are a woman of color, especially a Black woman, we see this even more predominantly.

If you are not performing femininity or really performing what white people expect you to look like, then you are potentially limiting your career opportunities. Again, all of money is linked back to some sort of either systemic oppression, systemic issue, and it's a really incredible opportunity for us to talk about it that way. And I think there is some sort of freeing element that happens, and I know this from these conversations that I've had with Her First $100K community members, is just the acknowledgement of it is just so refreshing of just like, “Gosh, I thought this was all me. I thought this was my mistake or my shame or my fear.” And the truth is that, yeah, maybe it's partially you made a financial mistake. It's probably you don't understand how to navigate the system because nobody taught you. And in addition, you're being told to do certain things that actually don't make sense for you as a member of a marginalized group.

So, we spend every chapter—going through the first half is like, “How did we get here and then what can we do about it,” and I think that, for me, that was a powerful way of showcasing how much of money is emotional, how much of money is ingrained in us, how much financial trauma we unfortunately have as individuals. And then, as opposed to just leaving you with that very depressing mindset or very depressing reality, I then try to give you a way forward in, hopefully, the least predatory, the least contributing-to-capitalism way possible.

RX: You talk about financial feminism not being just about finding individual financial equality, but also about leveling the playing field for all women. What can we do when we see a fellow female friend is in financial trouble?

TD: If you take anything away from my book, it is that we need to talk about money. We are more likely to talk about any other uncomfortable topic before we'll talk about money. Sex, religion, death, politics. We will statistically talk about anything else, because money as a society makes us deeply uncomfortable. And the truth is, any time real lasting change happens, it's when people have gotten comfortable being uncomfortable, at least for a period of time. And if you've never talked about money with somebody, or if you grew up in a family that didn't talk about money, this is going to feel really sticky, but shame lives in shadow. It's a great quote by Brené Brown.

The more you believe that you are alone and siloed, one, the more you'll retreat into yourself. But two, the more everybody else around you feels alone and siloed. So, if you can start having conversations about money, even just really small changes with your partner, with your friends, especially if you're a white woman with your women of color friends, and if you're a man listening to this, you have an obligation to talk to your women friends about money. It can be as very transparent as sharing your salary, but it can even just be like, "Hey, Rachael, I'm really struggling. I feel like debt is really stressing me out. Do you feel the same way? I just need to talk to you about it." Or I call you up: "Rachael, I got a promotion at work today and I really want to go celebrate. Let's go out for drinks."

"If you take anything away from my book, it is that we need to talk about money."

When you offer something first, when you are willing to be vulnerable first, most likely, that other person is going to be like, “Oh, thank God because I've been wanting to talk about this or because I need to talk about this.” That's how we start changing how we deal with money as a society, but also how we deal with money as individuals. It levels the playing field because if suddenly I know that this person's making 20 percent more than me, or if I know that this person is in a room where I should also be in order to get a promotion, or if I know that my partner is trying to learn how to navigate money with me so we can build a really beautiful life together, well, then suddenly everything starts to change.

But one of the narratives is don't talk about money because it's impolite or it's gauche, and that keeps you underpaid and overworked. So, we talk in the book about how to have these conversations or how to start these conversations. But really it begins with vulnerability and it begins with you offering something. And that is not only going to benefit you, it's going to benefit your relationships, it's going to benefit the other person you're talking to or the other people you're talking to. But it's also a very specific microcosm way that we can start to change the narrative.

RX: I hear you saying that we need to be vulnerable, we need to have conversations about money. In your book, you talk about how money is really psychological. What are some ways we can safeguard our mental health when we're approaching financial conversations and approaching financial planning?

TD: Great question. Thank you for asking. We really focus on putting your mental health first before anything else because we spend the entire first chapter talking about just how emotional and psychological money is. It is our longest chapter. It's the chapter I spent the most time on because we can't get a budget together, we can't learn how to invest, we can't negotiate our salary until we understand what sort of beliefs or narratives we have about money, what sort of emotions do we have around money, and what can we do about it. So, first thing is to offer yourself so much grace. You were probably never taught this, you probably haven't had a lot of financial conversations, and you're probably, especially if you're reading a book called Financial Feminist, you're probably feeling the systemic oppression real hard. So, the first thing is to just give yourself a lot of grace and understanding.

I mentioned this in the book, but we don't come out of the womb learning how to play the tuba or learning how to speak fluent Italian, yet somehow we believe that we should just be naturally good at money. But no one taught us and we don't understand it and it's jargony and it's full of finance bros named Chad, and it's like, of course you don't understand, and that's okay. So the first thing is to offer yourself a bunch of grace and to realize that we're going for progress here over perfection. I'm a personal-finance expert. I have done very well for myself financially. I have also made a lot of mistakes and continue to make a lot of mistakes. Probably two months ago, I accidentally overdrafted on my bank account. Like, shit happens. You will never be perfect. Leave perfect behind. We're just trying to make progress.

In terms of actionable steps, we talk incessantly both in our work on the podcast, on TikTok, on Instagram, but also in the book about emergency funds and just how important they are. Before you pay off debt, before you do any other part of your financial journey, you need an emergency fund first, and that is your way of both literally protecting yourself in case something happens, but also being able to sleep better at night. Knowing from a mental health standpoint that you have something in the bank is such a relief because an emergency will happen inevitably, and knowing that you're covered or at least partially covered—because the last thing you want to think about when you're in crisis is how am I going to afford this? That's the last thing we want to be stressing about.

The other thing, too, is when we have these conversations, when we start getting more comfortable not just with money but also with how money is exchanged or how money influences our relationships, you start to feel less alone. You start to view money as a tool rather than a barrier, because again, money is not inherently good or bad. It is a tool that you can use to build the life that you want. We have journal entries throughout the entire book and that's part of our homework of every chapter, and even if you have the audiobook, we give you the accompanying PDF. The words “accompanying PDF” haunt my dreams because I had to record them for every chapter when we do the audiobook. But you get these journal questions and I read them in the audiobook as well, and it's a great time to reflect and also for you to think about how is money affecting my life. How am I viewing money as scarce or shameful, or do I feel guilt when I do this? And instead, how do we hopefully get you to a point where money is a source of joy and stability and ease and luxury.

And I'm not even talking Saint Laurent, Louis Vuitton luxury. I'm talking about just like, “I can afford a coffee or I can go on vacation and I know that I can afford it.” That's a beautiful, lovely feeling, and through that reflection, and giving yourself grace and being able to talk about money in a really open way, the question to always ask yourself is “How do I use money as a tool to build the life that I want? How do I use money as a tool to be able to travel internationally once a year? How do I use money as a tool to be able to start that business I've always wanted to start? How do I use money as a tool so that I can afford to have children?” There's so many things. I would argue every single choice in life hinges on “Do I have the money to afford it?” And when you do, those options open up to you and you use money as a resource rather than a barrier to build that life that you want.

RX: Do you have any advice for people who are beginning their financial journeys, maybe especially Gen Z folks who are earning for the first time?

TD: Besides the shameless plug of listening to this book? I can't not shameless plug. I think the biggest thing is to find somebody who you connect with. So, find people who not only have good advice that's credible, but also that make you feel good about yourself. Somehow this is a novel concept.

There's not just one or two voices, and especially if you are a member of a marginalized group, if you are a woman, a person of color, a member of the LGBTQ+ community, if you're disabled, find somebody who speaks your language. And that might not be me, which is one of the reasons in the book that we have so many different expert interviews from people with a variety of different backgrounds, because one, I don't want to hear from me the entire time, and two, there's a lot of things that I can't speak to. I have a lot of privilege. I've also struggled with certain aspects, I've struggled with sexism, but there's certain things that I cannot and will not be able to understand or speak to. So, find people that connect with you. There are people who are talking about money in a way that will connect with you and make it accessible for you.

"We don't come out of the womb learning how to play the tuba or learning how to speak fluent Italian, yet somehow we believe that we should just be naturally good at money. But no one taught us and we don't understand it and it's jargony and it's full of finance bros named Chad, and it's like, of course you don't understand, and that's okay."

One of the criticisms that I get all the time is like, “Oh, you create personal finance TikToks. That's not as legitimate,” and I'm like, “People are on TikTok. I'm going to meet them where they are to make this scary, inaccessible thing as accessible as possible.” And if you like videos, great. There are dozens, probably hundreds now of YouTube channels, including ours. If you want a podcast, great. There's podcasts. There’s audiobooks, there are meetups you can go to and coaches that you can work with and educational platforms. Find advice that both connects with you and is accessible, and make sure you actually take the advice.

RX: This next question comes from one of my fellow editors. She wants to know, do you have any advice for millennials who may be interested in purchasing a home? Can it be done? Should it be done? Is it for everyone?

TD: Rachael, you've read my books so you know. If you were to take a shot every time I said “personal finance is personal” in the book, you'd be passed out on the floor by chapter 3, but truly, personal finance is personal. That's why we call it personal finance. So, I am a multimillionaire, I'm doing fine. I do not own property because I live in Seattle and I'm like, I don't know, emotionally, if I can bring myself to justify paying $900,000 for a two-bedroom house. I just don't know if I can do that, and as well as for the vast majority of people, that's just not a reality because they can't afford it.

Home ownership, if it's something you want to do, can be possible, but again, this is where systemic oppression comes in. This is where a student loan crisis and a housing crisis and millennials literally going through once-in-a-lifetime crises every five years, and it's like everything ends up snowballing. So this is where the grace part comes in, and two, actually ask yourself if you do want to be a homeowner. My life right now is not conducive to home ownership. I would like to be flexible. I lived out of Airbnbs for the last year. I did the digital nomad thing and I couldn't have justified doing that if I owned a home that I had to take care of. So, there's a lot of elements to this.

Unfortunately, for the vast majority of people, home ownership is not accessible in major cities because of all of the things I just mentioned, and this is where we can't just change our own personal finances. We have to demand better of the system that exists through policy change and voting and protesting and everything else. So if you're a fellow millennial like myself, home ownership might be an option for you. It just might look different. So maybe that's not an actual home. Maybe that's some sort of condo or townhouse. Maybe that is owning a home, but you rent out one of the rooms or maybe there's a basement apartment that you can rent out. Or maybe for you, that's just not what you want to do, but you've been told it's the "right" thing to do, which is what I was told.

I think I tell the story in the book, my parents were like, “You have to buy a house because if you rent, it's throwing money down the toilet,” and I think we've all heard that. No, it's not. It's buying or affording a place to live, and also the luxury of if the toilet overflows at 11 p.m., that is no longer my responsibility. So the TL;DR: I don't know you, I don't know your life. Home ownership for plenty of people, I think, still is possible, but for plenty of people it isn't, and the American dream of the white picket fence and of the suburban home is just not achievable for plenty of people, even those who are making "good salaries," because of all of the systemic oppression that exists. And if you want to play another drinking game, every time during this interview I've said the words “systemic oppression,” go ahead and take a shot.

RX: That last bit was not real advice for anyone listening at home.

TD: No, no, no, drink responsibly. Thank you.

RX: So, what topics are you thinking about exploring next? Have you heard anything maybe from some of your followers that has inspired you to research something new?

TD: Oh, that's a great question. I learned so much writing this book. There was so much of me reckoning with my own privilege, me trying to write a book about money in a way that was about surviving capitalism and doing your best to not contribute to the predatory nature of capitalism. So, I learned so much writing this book, and I hope people learn a lot reading it and I hope people take away a lot. I've spent a lot of this interview talking about how everything seems to be screwed up, which in many ways, it is, but if you do read this book, I hope you leave with a sense of hopefulness, because there is so much specific advice around “This is what a Roth IRA is, this is how to open one, this is how to create a budget without wanting to die.” So, yeah, learned a lot writing this book and will continue to learn a lot from people around me.

What is something that I've learned recently about money that I didn't know? We do weekly interviews on the podcast with new guests all of the time. One of my favorite things I just learned from a career expert we had on the show: She thoughtfully calls stay-at-home mothers non-compensated working moms, and I just loved that reframe, because she argues that we have weirdly pitted stay-at-home moms versus working moms against each other, and how stay-at-home moms, of course, are working mothers. They're just not compensated for that work in a traditional sense. So, I have to really try to actually update my language to rather than calling stay-at-home parents stay-at-home parents, it's non-compensated working mothers or fathers or parents. So, I think that that's one thing that I've learned that has been great.

RX: Speaking of learning from this book, was there anything that you learned maybe about your own advice or the advice of your contributors during the recording process or during the listening process that maybe you didn't notice during the writing process?

TD: Oh, great question. I actually wrote this book how I would want it to be read out loud. I think a lot of authors are writing in a way that is maybe more lofty than they would speak in everyday life, and one of the things I'm most proud of in this book is it has a very distinct voice that is 100 percent Tori Dunlap. It is 100 percent how I would speak to you in real life. So the magic of recording this audiobook is it is exactly how I intended it. Every Timothée Chalamet reference, every aside—woven throughout this book are just so many pop culture references. I'm calling it the Gilmore Girls of finance books, where I'm dropping references to things. If you're listening to the audiobook, it's being read exactly how I intended it, and I think that was the most fun part, is getting to record the audiobook and read in a very casual way, just like I would if I was speaking to you.

There's also, I'm such an emotional person. I cry at anything and everything. I cry when I'm happy, I cry when I'm sad. I've cried today, I cried yesterday, I'll cry tomorrow. Like, I cry all the time, and one of the things that happened was when—I'm even tearing up talking about it—when I read my acknowledgements and all of the people—aw, see, I'm crying right now. When I read my acknowledgements, thanking my friends and my family and our community and our team, I had to do multiple takes to the point where I was so snotty and gross, I couldn't get through it. But I wanted to keep that in there. So I got to probably the fifth or sixth take on some of these where you can still hear the emotion in my voice, but you can also understand the words that I'm saying, and that was something that I wanted to keep. I didn't want the very sterile audiobook narrator version. I wanted it to feel like I feel when I wrote it or like I felt when I was recording it.

I'm going to cry talking about my mom and dad. I'm going to cry talking about our community. I'm crying right now, clearly. I think that was the other part, too, the ultimate thing for me is not only fulfilling the promise that I made to childhood me, but knowing that this book is going to impact people, and seeing it on a shelf or hearing it in somebody's ears, that is the feeling that I'm looking forward to most. And I wanted you to be able to hear that passion and hear how much I care about this work and how much I know it is my life's work and what I was put on this earth to do. And I think that's the perfect part of this in audio format, is you get all of that and more.

RX: Tori, I think this is the perfect place for us to end. Thank you so much for speaking with me, for being your authentic self. I am rooting for you and Timothée Chalamet. Let me just say that, as I was listening to your audiobook, I was like, how do we make this happen? If you are listening at home, you can listen to Financial Feminist by Tori Dunlap on Audible. Enjoy. Go and get it. It's wonderful. Thank you again.

TD: Thank you so much. And I joke that this entire business is just a front for me to try to negotiate my way into a room with Timothée Chalamet. Don't care about financial feminism at all. It's just a Timothée Chalamet campaign. Obviously kidding, but yes, you've got plenty of Timothée Chalamet references and if you don't know who that is, Google it. You do. You know who that is. Thank you for having me. I'm so excited for people to listen.

RX: My pleasure. Thank you.