Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

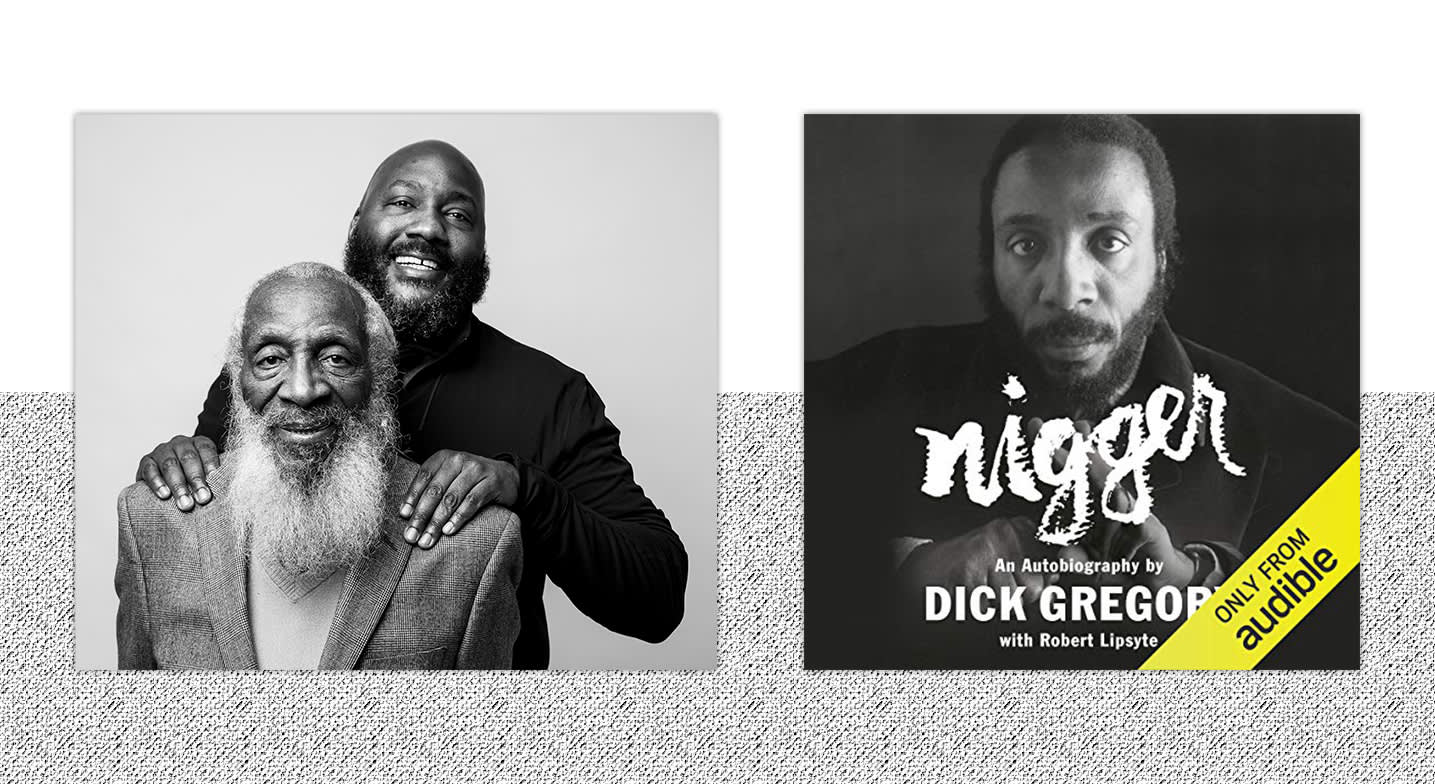

Abby West: Hi, Audible listeners. I'm your Audible editor, Abby West, and I'm talking today with Dr. Christian Gregory, son of the legendary comedian and activist, Dick Gregory. And we're talking about his father's groundbreaking memoir, which is now available in audio for the first time only from Audible. Welcome, Dr. Gregory.

Christian Gregory: Thank you for having me, Abby.

AW: So happy to. And I'm going to cop to the fact that I did not say the title of your father's amazing memoir, which is an important work inside and outside of the African American community. Just in general.

CG: Absolutely.

AW: And that speaks to the controversial nature of the title, which I'll let you dig into with me a little bit.

CG: Well, yes, Abby. And any of your listeners who know Dick Gregory know that he never shied away from controversy. Matter of fact, he was a self-described agitator, which was part of his logic and thinking when it came time to name his memoir. My dad went on to write many books, but his first book, his autobiography — it's a complicated reason, and we'll do a deeper dive into it — but he ultimately settled on the name Nigger for the title.

He wrote the book in 1963. It was released in 1964. It created controversy then and potentially even more controversy now in 2020, so it really is quite telling. And the story of how that came to be is almost as enlightening as the book itself. It really is. It speaks to a cross section of Americana. And my dad's story is so uniquely American. So this title really kind of forces you to stop in your tracks and think about what the climate must've been then to push this very successful comedian and entertainer to take a significant hit from the marketability of his book by using such a strong, provocative title as Nigger.

AW: That's exactly true. And I think I read somewhere that he considered it less provocative, than defiant. That it was a stance in a way, not meant to titillate anyone, it doesn't really add to marketability in the usual sense, but it seemed like it was less so to provoke than to take a stance. Is that right?

CG: That's absolutely correct, Abby. My dad was a master teacher, more than he was anything else. And he was the voice to so many movements. And so when he came up with the name, it's important to remember the climate. I mean, the '60s were a very challenging time. So here you have this poor African American born in 1932, in a very Jim Crow segregated South. Racial hatred was all around him. He probably heard that word for — not probably, he did hear that word frequently, but it was the intent behind the word that led to him having such a troubled relationship with it.

When he was 14, he was working as a shoeshine boy — my dad had a lot of jobs. He definitely, in a good sense, was a hustler. A man asked him to shine his wife's shoes, and as he was shining this white woman's shoes, he gently grabbed the back of her heel to hold her shoe steady and a white man next to her was so outraged by a black boy, because he was 14, a black child, a teenager placing his hand on a white woman's foot that he kicked my dad in the mouth and knocked out many of his front teeth.

He would always say, ‘Wars and battles are not won by singers and dancers. They're won by activists...'

This was a time in the 1930s when if a white man or woman was walking down the street, a black man had to step aside and look at the ground. It was a profoundly different time. And in 2020 it's difficult to go back and look at that lens. But that's the reality that shaped Dick Gregory. So here you have this [man], now bigger than life. In 1961 my dad was one of the largest — not just black — largest entertainers in America. He was fresh off of his January 13, 1961 Chicago Playboy Club performance. That was really his breakthrough. And from '61 to '63 when he wrote this book, he was rocketing into American households all over.

And many folks with that level of success would have definitely shied away from such a colorful title. But my dad never forgot his roots. He never forgot the pain and discomfort that ugly bigotry and racism thrust upon this child. And so, in a sense, he wanted to say, "Okay, America (specifically white America), you called us this, and now I'm going to put this out here in the light of day for you to deal with the ugliness of it." That was in 1963, and now in 2020 it's still a word that, amongst Black and white folks, creates and causes quite a bit of discomfort.

The word's used so much now... I joke from time to time, when my dad on the dedication page of the book says — and this a paraphrase — “Dear mama, I'm dedicating this book to you. From this point on whenever you hear the word ‘nigger’ just know they're advertising my book.” Well, I say now in 2020, looking down from above, my grandmother must say, "Wow, they sure are really advertising my son's book a lot.” And so times have dramatically changed.

AW: They have changed, but in some ways, it's gotten more reactive. I read that, I think it was 2015 or so, there was a professor who had to resign because of the hullabaloo around her recommending or taking this book to her class. And I believe your father wrote in defense of her.

CG: Dean Jodi Kelly. My father and I flew out and met with her. She's a dear friend. She was friends with me and my dad. She spoke to my dad not too terribly long before he passed away. And that's Dick Gregory for you. Part of why we wanted to reach out to her, because we wanted to get the true story. Context of how a word's use is profoundly important. So just because someone's a Dean, she could have very easily, still in a very disrespectful way, said the title of the book in a derogatory way. So we wanted to get a sense of what her soul was. And we spoke with her on a lengthy [talk] before we went to bat for her. We wanted to be sure.

And when we spoke with her, it was clear she knew this autobiography, front and back. She quoted it from beginning to end. She knew Malcolm X's biography. As a white woman, she grew up in the movement, and as we know, the civil rights movement was not solely black folks. So it was folks who were fair minded, and wanted justice for all. And Dean Kelly was definitely that. It was very unfortunate that she lost her job. But she's a marvelous human being, and I'm honored to call her my friend.

AW: That's the main thing. And that civil rights activism spirit — he marched on Selma, he was with Dr. King in many, many circumstances. He fought apartheid in South Africa. He was protesting the Vietnam war. He took his comedy and melded it with his activism. From your viewpoint and vantage, how did he pair those two, or how did that work for him?

CG: My dad was always so topical, and I want to circle back to your question. But just in the last week or so watching the news, there was a story on about intermittent fasting. And Dick Gregory was known for just fasting for health, but also starving himself to bring about change. But also, he spent six months in an Iranian jail cell in 1979, refusing to leave and to the US hostages were released. So he was on the front line. I frequently say there wasn't a movement that was rooted in fairness and love that Dick Gregory, some of his spiritual and activism DNA, is not on some aspect of. Since he was the little guy for so much of his life, he knew nothing but to advocate for folks who were marginalized.

And that became, really, his calling. There were times, as my father got older, that he was almost embarrassed — and that is the correct word — embarrassed by the fact he was an entertainer. He would always say, ‘Wars and battles are not won by singers and dancers. They're won by activists. They're won by soldiers. They're won by folks going out there and fighting the good fight to bring about change, to make countries better, to make humans better, to take care of the weakest amongst us.’ These were his ideals. These were the things that he instilled in us Gregory children. This is how we were raised. We were raised on a farm as vegans back in the 1960s and '70s, and we were called “health nuts” back then. We'd go to a restaurant, there was nothing to eat. Now we have not just sections on the menu dedicated to us, but whole restaurants dedicated to us.

So he was a visionary. And his vision didn't allow him to simply be an entertainer. And he was always funny. Even in nutrition, whatever he did, it was rooted in comedy. Comedy is so disarming. When someone uses wit and humor, it really disarms you and allows a message to almost sink into your brain, get past your defenses. And that's really how he used to shake up a lot of his white audiences. Because they would be giggling and laughing, and then it had almost a boomerang effect when it came full-circle back to them and they said, "Wow! Holy smokes, this is deep.” And it almost made them feel silly for some of the racist thoughts that they had, almost made them feel silly that this is a teachable moment. And nothing teaches you more when you're not sitting in a classroom and you're living it in life's classroom, which is life.

His affinity was much stronger towards other activists: Dr. King, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X. He was friends with and spoke frequently to JFK. He was friends with RFK. There were a lot of folks in my dad's world who were cut down by assassins' bullets. My dad understood terrorism. Long before it became a household reality for America, it was a household reality for African Americans. And my dad, he was a superhero. He had his chest out, and was always the first to respond.

And he walked away from the height of his success and fame. Very few people do that. They'll write a check, send money, give you a paragraph or two. Actually, Bill Cosby's on the record of saying the only reason he was able to break into comedy is because Dick Gregory walked away. And that void that was left created a void for so many other comedians. They would have made their way, and worked their way through, but it created almost a vacuum that they were sucked immediately into.

AW: Right. He was pretty active right up to the end, correct? There was no holding him back. But did his attitude change or evolve as he got older? Did he stay as optimistic about the potential for change?

CG: Yes, and let me qualify that. So everything that Dick Gregory did, as he would say, was always loving and lovable. I frequently say no country for old legends. My dad, in his later years, was dealing with some dementia. He was beginning to deal with some of the signs of Alzheimer's, and just the regular kind of wear-and-tear on his body. My father was chronologically 84 when he passed [in 2017], but biologically he was like a good 120. There were a lot of miles on that body. He ran across the country twice, running the equivalent of two marathons, from Los Angeles to New York to bring attention to global hunger. So all the way up into the end, he was on the front line. He was a true blue activist.

He lectured. And he stopped performing in comedy clubs at a rather young age, because he really became a health guru, and he didn't feel comfortable for young people to come into nightclubs where there was smoking and alcohol while he was trying to yes, entertain, but also “enlightened edutainment.” Teach folks about the importance of taking care of their body. That transition really is what launched him onto the college circuit. And so he spoke at so many colleges and universities, and there's no time in our life where we're more of an apt pupil than when we're in our late teens, early twenties. I mean, people from some of the smallest, off-the-radar-screen colleges and universities all over the world come up to me and say, “I remember when your dad spoke.” And it's for a fact, if he was only doing comedy, I know he wouldn't have had the impact with young developing minds that he did. But he was lecturing up towards the end.

I'd say when my dad was about 79 he spoke at a high school, and he had lost that ability to sequester in his frontal lobe what was appropriate language for a particular audience. And so we got a pretty colorful letter from the principal of the high school, who was pretty disturbed by the language. My dad was a master in his frontal lobe. He had his nutrition lectures, he had his civil rights lectures, he had his comedy routines. And then you have the real kind of off-the-charts stuff that he would only discuss and have the funnies with when there was a small private group around. Well, that started to leech into the other segments of his lecturing. And it became obvious to the family that we really need to shift focus.

So we shifted back to my dad exclusively performing in comedy clubs. And it was a different, unfiltered [performance]. My dad was always unfiltered, but he was really unfiltered. It was some of his funniest stuff, and not just making fun at his age, but really showing that generational wisdom that he had acquired over just a lifetime of [being] almost like Forrest Gump — he was there. He was there, boots on the ground at so many events that we simply read about. He was there and he was making his presence known. So the week that we lost him, we canceled eight comedy shows that he had already been scheduled for that week. It wasn't uncommon, because many of the comedy clubs, they have a 45-minute time slot where he may do three shows in one evening. I don't know when the man slept.

And so he traveled all over the country by himself still, even at 84. Not because he had to — many of us would've went with him. But he insisted to do it. He reverse-aged before your eyes the moment that a light hit him on a stage. He went from an old 84 to a very young 64. And it was just miraculous to see how much life he got from the audience and from the folks who loved him.

AW: That's great. You mentioned that this is the first time the memoir is going to be available in audio. What does it mean for you for this seminal work to have a new iteration, and for you to be recording the foreword for it?

CG: Well, for me, sure, I'm Dick Gregory's son, but I also managed my dad for the last 20 years. I was a collaborator on all of his writing projects. Me and him sat shoulder to shoulder as we drafted the response to what happened to Dean Jodi Kelly, which was a powerful, very powerful piece that we submitted for a scholastic magazine. So for me, I've done basically what I'm doing now for the last 20 years.

But a lot of people forget this because I'm on a three-year leave of absence from my practice, but I'm a chiropractor by trade, and for this book to be available on an audio format, for me, it's just profoundly important. My dad was all about, get up and move, health and wellness. We both loved audiobooks. I mean, we'd put books in and just slowly walk around the labyrinth as we were absorbing that information.

And I think it's wonderful for your listeners to be able to be good mammals and move the 206 bones and 650 muscles in their body, while they're stimulating the biggest muscle, their brain, by just absorbing all of this information. Not to mention as you're moving while you're listening, there's more blood going into the brain, so retention and comprehension is higher as well. So I'm elated, to answer your question. To have Nigger available for the first time as an audiobook, and to have it on your Audible platform is just…I have no words. I'm just profoundly grateful and excited, and eager to see the response.