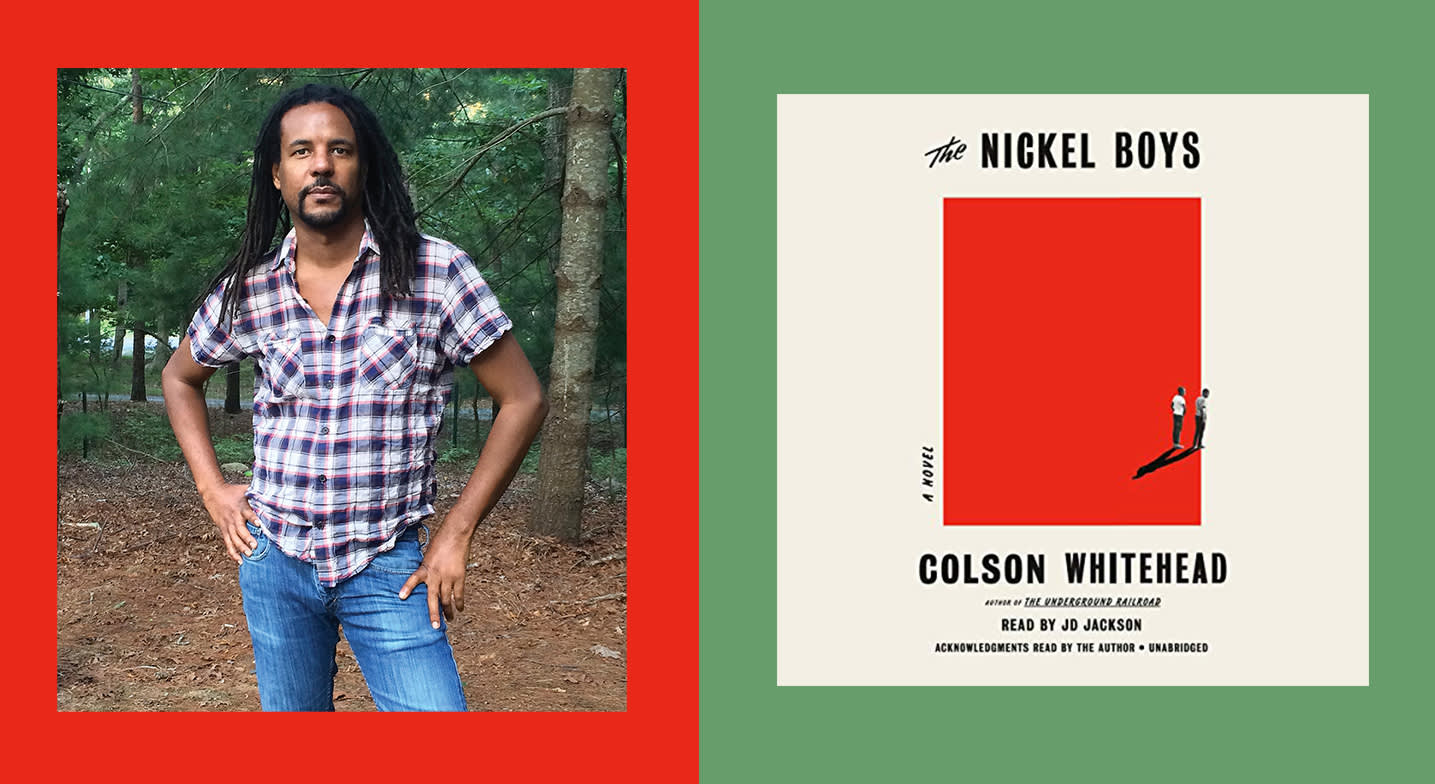

Colson Whitehead is no stranger to addressing the sins of the past with his pen and his imagination. He did it most famously with The Underground Railroad, where he tackled slavery with an element of magical realism that saw the Underground Railroad that helped so many enslaved people escape as something more than metaphor. He framed it as a secret network of tracks and tunnels beneath the Southern soil operated by engineers and conductors, and it resonated so that a slew of awards followed.

With his latest work, Whitehead gives a fictional take on the real-life horrors that happened at the Dozier School for Boys in Florida for more than 100 years, through the eyes of a young black boy who suffered terrible, life-altering abuse there.

Listen in as he talks with editor Laura Michaels about why he was compelled to tell this story, how he approached the research, and what's his involvement with The Underground Railroad Amazon series.

Note: Text has been edited and may not match audio exactly.

Laura Michaels: Hi, everyone. I'm Audible editor Laura, and I'm here with Colson Whitehead. He's the author of nine books, including The Underground Railroad, which won both the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. Now, he's back with Nickel Boys, a heartbreaking story, which takes place in Florida during the Jim Crow Era. We meet Elwood Curtis, who is just in the wrong place at the wrong time and ends up sentenced to the Nickel Academy, a reform school for boys.

There, he befriends Turner, and the story unfolds further about their time at the school and the atrocities they endured. It's a book that I haven't been able to stop talking about. So I'm excited to speak with Colson today. Hello!

Colson Whitehead: How do you do?

LM: I'm pretty good. As we were talking about before, it feels very weird to be so excited about this book because it is so heartbreaking and so emotionally jarring that it feels... almost inappropriate to be so excited about something like this.

So, jumping into the story... It's based on a true story about a school called the Dozier School for Boys or the Florida School for Boys. So, how did you pick this topic?

CW: I first heard about the school in 2014 in the summer. And it was a reform school for boys opened for 111 years. You could be sent there for graffiti or being a truant. Also, if you were an orphan and had nowhere else to go--if you were a ward of the state, you could be sent to this place. And the idea was that we keep juvenile offenders away from grownup criminals so they don't come habitual. We'll give them classes. We'll give them work training. And maybe we can rehabilitate them and set them on a good course.

Unfortunately, as happens in places like this, where guards and supervisors think they can do what they want, there's a lot of abuse--physical and sexual. Some kids ended up being killed and buried on the grounds.

And this went on for many years. There'd be reforms, investigations, and they finally closed the school because it was just too out of hand. And they started exhuming the official graveyard, where kids died of pneumonia or whatever. And then they found some other grave sites, unmarked graves, and turned out that there were boys who were buried with blunt-force trauma to their heads, with shotgun pellets in their bones.

And at that moment, some adult survivors, students who'd been there in the '50s and '60s, started making a group and coming forward with their stories. And finally, the truth of this reform school came out. A lot of news came out in 2014. And it seemed crazy. I'd never heard of this place. And also, if there's one place like this, there are many reforms schools.

And it seemed worthy of taking up just because I felt I wanted to tell their story.

LM: Yes. I read the whole thing, and then I went back and listened to it, since the audio wasn't ready at first. Afterwards, I went down this Google rabbit hole of reading all these articles about the school and was just so confused as to why I hadn't heard of this. Why wasn't it publicized more? It just closed in 2011.

CW: Well, no one cared 50 years ago about these boys. They had no protectors, no one to stand up for them. Certainly, the institutions and the government are not going to dig too deep. And in terms of how it gets into the news now, a lot of people have a lot of other things to worry about than some dead boys and unfortunately abused children. And that's just the way society goes sometimes.

They actually found 27 more bodies this spring in unmarked graves. And those are more boys who can hopefully be identified by DNA or by their teeth and dental records.

I think the fact that we can pass over an atrocity like this so quickly speaks to why I felt I had to write this story.

LM: Yeah. So when you were doing your research for this, did you speak to any of the survivors? Or was most of it research through periodicals or journalists?

CW: It was mostly through newspaper accounts. It was covered very extensively in Florida papers, [especially] the Tampa Bay Times. Ben Montgomery was a reporter who did a lot of work on it.

There are memoirs of former students, photography archives of the place. And there's a woman named Erin Kimmerle, who's a professor of anthropology at the University of South Florida, and she was tasked with exhuming the bodies and identifying them. And she and her students made this really comprehensive report on the school and how different folks died.

So I had enough to write about the place and make my own sort of version of it. Nickel Academy as opposed to Dozier.

And I didn't want to talk to anybody because I wanted to have my own boys and my own students there. It wasn't until after the book was done I started getting some emails from students and talking to them.

LM: Okay. So, speaking of the boys that you decided to fictionalize, Elwood and Turner. Are they based on anyone in particular or just from your mind?

CW: I had a place, and I wanted to have characters to do different things that I wanted them to do in the book. And so they're all from scratch. Now sometimes you're in this part of me and my characters. Sometimes people I know. Depends on the book.

With the Underground Railroad, Cora, the main character, has the least amount of me in her, which is probably why it's my most popular book.

But then in terms of Elwood and Turner... Elwood, as we said earlier, he's a straight-A student, a good kid, and very much believes--the book takes place in 1963--that we're entering into a new age in terms of racial equality. And he's an optimist. And then Turner is an orphan. He's had to survive living by wits and can really see this sort of machinery that grinds people down. And he's more of a pessimist or a realist.

And I think I had those parts of my personality. I used the two boys' different points of view, their philosophical points of view, to work out the dilemma that I was having. How can I-- especially the last two years, with the country very divided -- envision the future? How can I address my optimistic side and pessimistic side?

So, the two boys became a way for me to sort of think about where we are in the country.

LM: Okay. Interesting. I feel like throughout the book they kind of become so similar. I feel as their friendship blossoms, they are almost rubbing off on each other.

This takes place in the '60s, and there are all the atrocities that are still happening today. As we said before, the school didn't close until 2011. Why did you decide to write about a school like this in that time period as opposed to present day or 10 years ago?

CW: I've written a few novels that take place in contemporary America. And I thought that sort of said my piece in terms of where we are right now. So, I didn't want to repeat myself. And I think there's a virtue and value in finding stories from the past and finding ways to understand where we're coming from and where we're going.

So, writing about a time that wasn't my own seemed to make sense. All the boys who've come forward, the survivors, are white. I wanted to try and figure out what it would be like for a black student at Dozier. And it seemed at '63, '64, where we are making advances in terms of civil rights and enacting laws to protect everybody's equality...

but also, there's the idea that you're fighting against centuries of oppression in a system that's been designed to retard progress. The early '60s seemed like a good moment of possibility but also [with] very real obstacles in terms of moving forward.

LM: Yes, and so the book is written in a very interesting way. It goes back and forth between the past and then present day.

CW: About two-thirds of the way through, we picked up Elwood in New York and he's left Dozier. We're not sure how he got out, and we trace him through the decades as he grows up and tries to recover and make a coherent, full self.

LM: Right. And during those chapters, the whole time it's kind of like they're soothing because I was like, okay, he's out. He has a GED. He has a job. Everything's going to be okay. The story's going to end okay. Is that what your intention was of writing it in that form?

CW: The intention is up to the reader. I just try to lay it out.

LM: Okay.

CW: But even if you get out, how do you recover from the abuse? How do you find a way to love? Love other people, love yourself? The survivors' organization is called the White House Boys; the place where boys were beaten on a canvas is called The White House. It was a utility shed that they used for beatings.

And their website has a lot of stories of what happened to people after they got out. They turned to drugs or alcohol. They never were integrated into society, had various problems becoming a normal person. No one's normal. But joining the straight world.

And so, he is out, and we see him in the '70s and '80s and '90s. But how has the Nickel Academy formed him? Limited his choices? That's what we're sort of following in those chapters.

LM: Right. Since we're talking about the audiobook--I read the book when I could first get my hands on it. And then I went back, and I listened to it again, which is actually very fascinating once you finish to hear it from a different perspective.

And I had never listened to J.D. Jackson, the narrator, before. When I was listening to him portray Elwood, portray Turner... I was like, okay, this makes sense. This sounds, as I am assuming that they sound in my head. How involved were you with picking the narrator?

CW: It's funny with the audiobooks. The first two of mine, I had no input. I did run into the actor who read my first two books, and I had to apologize for using so many ten-dollar words that don't really fall of the tongue very easily.

And I've read two of my own books--the short ones, The Noble Hustle and The Colossus of New York --and it's such a hard enterprise. I really admire people who can pull it off.

I can do short readings of my fiction, but I can't do voices. I can't do characters. With the Underground Railroad, I was trying to voice the slave masters and all my southern, sadistic white men sound like Foghorn Leghorn. "I say, I say..."

LM: [Laughter] That's a pretty good impression.

CW: And so, I'm not an actor, but thanks for appreciating. I think for fiction, you need an actor.

I haven't heard the finished version yet. I didn't actually know it was done. I'd love to hear it. But when they were planning it, they gave me clips of three different narrators. And they were all good. But it seemed the one we ended up with had the gravity in understanding.

He was doing, funnily enough, a Louisiana accent. And we're like... they're not from Louisiana. But he's like... he can do Florida. And that's a skill most writers can't pull off, the real sort of acting and then selling the drama.

LM: Got it. When you're writing the story, are you thinking about how the characters sound in your head? Or do you just want to get their point of view across to the reader or listener?

CW: I edit on a computer. I write it down, I print out and edit, and those are two important ways. And then also, I read things aloud. And I think when I read things aloud, I can figure out if there's an extra clause, an extra comma. There's a part of the sentence that needs an extra word for emphasis.

And then there's a rhythm to the paragraph that helps you sort of shape the way things are going. As an editing tool, I read things aloud and definitely when I figure out what's a good reading for a bookstore or a signing, the parts where I sort of settle in and have fun... and the dialogue's sort of easy to do.

LM: Okay. I notice that Cora in Underground Railroad, when it starts she's 11 or 12, and Elwood is 12. Are you ever concerned about how someone will be able to kind of interpret that character as they grow into an adult or just older?

CW: In terms of the narrator reading it, that's their job, and I trust them that they know how to do it. And a lot of the books--at least those two books--are looking back into the past, and so there's a certain remove that I think helps.

LM: Was there any reason that you had, in both Underground Railroad and Nickel Boys, the main character begin at that age? Is there something about that age in particular?

CW: Not so much. In terms of Dozier, they had to be under 18. That's when you get out. And Cora in the Underground Railroad, it was marking her progress into womanhood. She starts off as a child and grows into a young adult. She starts off as a piece of property, an object, and becomes a person across the book.

And so, you start in this unformed moment and part of their dramatic arc is coming into your personhood.

LM: In a lot of books there'll be a quotation from a politician or a philosopher in the beginning of the chapter. And I'm a little embarrassed to admit, I never really read those. But you incorporated a lot of quotations from MLK within the text.

CW: Sure, yeah. They're not ever-grabs. They're quotations from Martin Luther King's speeches that are very important to Elwood. He's grown up reading LIFE magazine and seeing Dr. King march with other activists, making strides, and his idea that he can change the world comes from that incredible group. And so, I wanted to find speeches here and there that would speak to his situation at different times.

LM: When you were writing it, because it flowed so seamlessly, did you have specific lines from his speeches that you knew that Elwood really took to that you wanted to incorporate, or was it off the cuff almost?

CW: Not off-the-cuff, because I can't really quote anything besides the most famous couple of sentences.

LM: Right.

CW: But, I made the decision that he's inspired by Martin Luther King, so I had to find the speeches, the paragraphs that can most serve his stories. There are so many things to choose from. But what actually serves what I'm trying to do in the book and what serves Elwood's psychology. It's pre-internet. You can't just call up things on demand.

And the way that you could access people that Martin Luther King's speeches were from LPs and records. So, he has a long playing record of a few of his speeches.

And then I sort of pick which ones, which sections will serve the book. And that was a great part of the research because I hadn't listened to King in a while. And hearing his voice and getting reacquainted with his vision was really invigorating. And you see how some like Elwood can be swayed.

In some ways, Elwood is so idealistic, he seems impossible. But there are actually a whole cohort, thousands and thousands of people who were engaged in the same kind of work that animated him.

Sometimes research is a slug, but it feeds the book. And in this case, it was really lovely to hear Dr. King's voice.

LM: So, when you were doing research on his speeches, were you pulling up old recordings, or are you going right to YouTube?

CW: Both. And that's a great thing about YouTube--the record that I picked for Elwood is up there.

LM: Right.

CW: And does this record work or that? Is there video of this or that speech? I don't want to have to leave the house. So, the last 20 years in terms of information technology has been a great boon for me.

LM: That's great. I like to leave the house occasionally. When you live in New York, it's pretty worthwhile.

CW: Certainly.

LM: Since Elwood is almost so... I don't want to say innocent and naïve... since he has such a rosy outlook on life and is such an optimist. And his relationship with his grandmother I found extremely interesting because it's kind of like he keeps her almost innocent while he's in this school for boys where he's just facing horrendous and unimaginable things. Was that purposeful to kind of shield her from these horrors?

CW: It goes both ways. She's a previous generation who was taught keep your head down or else it'll get chopped off, and that's the reality of Jim Crow and the sort of fierce segregation. If you stand up, the white world will destroy you.

So that's her point of view, and when Elwood starts marching to protest a segregated movie theater, she was very much against it because she doesn't want anything to happen to him in the same way that her husband was punished.

And Elwood, there's that same sort of protective instinct. He's being brutalized at this place but doesn't want to cause any distress for his grandmother. And they have different reasons for protecting each other. And that's the way family acts sometimes.

LM: Right. Those parts during his conversations with her--I want to scream at him and just be like, "Tell her. Tell someone!" But I also could totally understand what he was saying. You don't want to hurt someone you love by sometimes giving them an honest answer about things.

Since I don't want to give anything away, I'm going to kind of pivot from the plot of this book, and I want to talk a little bit about Underground Railroad. So, this is kind of mundane. My mom purchased your book. And I know that sounds kind of lame. But I've literally not seen her read a book that wasn't from the library in forever. The fact that she bought it was a big deal.

So, this is kind of a loaded question. But since that has released, how's your life changed? Have you been able to use this giant platform that you have for certain causes, certain things that you believe in?

CW: I think I do it through my writing. I do a lot of benefits for various causes. And I'm happy to do that. In terms of my platform, I think it really is what I can do with my books. We're talking now, and Nickel Boys is going to come down in a few weeks. But it's come out in foreign editions, and it's come out in Germany just because they like to get things out so that people don't buy the book in English as opposed to German. Because in Germany a lot of people buy books in both German and English.

LM: I didn't know that. That's interesting.

CW: And I was asked, so you're writing op-eds about the Dozier school? Are you giving speeches? And I write fiction. I'm not a non-fiction writer. And I think I prefer to speak through my books.

LM: Underground Railroad is being adapted into a television series for Amazon. Have you been involved with the production at all?

CW: I'm hands-off. It's being done by Barry Jenkins, who directed Moonlight and If Beale Street Could Talk. And I signed off on allowing him to adapt it. And we talked, and his ideas were really great. We've had a few conversations about different plot points, and I think he was really savvy in terms of his ideas of how to take something that works in a page and make it work on a screen. Because they're two different media and they demand different kinds of storytelling.

So, apart from that, I wrote it once. I don't want to write it again, and there are other things I wanted to work on, like The Nickel Boys. If I had been more involved, I wouldn't be done with that book. And I figured I only had a limited amount of time on Earth, so I should probably work on new stuff as opposed to the old stuff.

LM: Okay.

CW: I'm not dying or anything, as far as I know. [Laughter] But I've spent enough time with Underground Railroad. I might like to get to some other things.

LM: So, what is next then? I know Nickel Boys still needs to go out, and I need to stop talking about it one day. I'll stop talking about it when other people have the chance to read it.

CW: I usually take a lot of time off in between books, like a year or a year and a half to decompress, or I'm teaching. Fortunately, the success of the Underground Railroadallowed me not to have to teach anymore, and I have more time for my writing, which is really great.

And so, I finished Nickel Boys last July and sort of went back to a novel I have an idea for. I started writing it in October. I didn't have that sort of break, and it was really good over the one term in spring to work on this new project. It's a crime novel set in Harlem in the '60s and very different.

I think if the Underground Railroad and Nickel Boys deal with institutional racism and our sort of foundational errors in this country, this book is very different in terms of its language and the characters and the kind of research. I'm researching Harlem in the '60s, and it's been a lot of fun. So it's been nice to do something different.

LM: That's interesting. Are you going to take some time off? Any fun plans? Are you going to travel or just sleep?

CW: Last night was good. I'm a two-naps-a-day'er. I'm sure I'll continue that trend. But I'm hitting in the road with the book in July and doing a book tour, and it's coming out in different countries like Norway, Sweden, Holland, and Italy in the early part of the fall, so I'm going to go to those places and see how they relate to this American story of how things were here in the '60s.

So, I'm pretty busy. But I have downtime for binge-watching and playing video games and goofing off in between.

LM: That's perfect. That's great. It's the summer.

Colson, thank you so much for speaking with me today. It's been so wonderful. I'm so excited for Nickel Boys to come out and for everybody to listen to it because it is my favorite book that I've listened to this year.

CW: I'm so glad. It still hasn't reached the outside world yet. It's still a few weeks away. So, I'm glad that so far people have been really supportive and sort of understood what I was trying to do.